|

ix | ||||

| Foreword | xi | ||||

|

|||||

| Preface | xiii | ||||

| Prologue | 3 | (6) | |||

| PART ONE The Early Years: 1926--1956 | |||||

|

9 | (10) | |||

|

19 | (13) | |||

|

32 | (13) | |||

|

45 | (20) | |||

| PART TWO The Career Begins: 1957--1959 | |||||

|

65 | (16) | |||

|

81 | (13) | |||

|

94 | (11) | |||

| PART THREE Ascendancy: The 1960s | |||||

|

105 | (10) | |||

|

115 | (12) | |||

|

127 | (14) | |||

|

141 | (10) | |||

|

151 | (14) | |||

| PART FOUR Gaining the Heights: The 1970s | |||||

|

165 | (12) | |||

|

177 | (15) | |||

|

192 | (18) | |||

|

210 | (15) | |||

|

225 | (16) | |||

| PART FIVE Winding Down: The 1980s | |||||

|

241 | (11) | |||

|

252 | (14) | |||

|

266 | (10) | |||

|

276 | (11) | |||

|

287 | (13) | |||

| Epilogue | 300 | (11) | |||

| Performance History | 311 | (31) | |||

| Opera Roles and First Performances | 342 | (1) | |||

| Selected Discography and Videography | 343 | (2) | |||

| Notes | 345 | (22) | |||

| Selected Bibliography | 367 | (4) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 371 | (2) | |||

| Index | 373 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Prince Albert

JON VICKERS'S PARENTS WERE CANADIAN, OF ENGLISH AND IRISH descent. If they had not been driven by poverty to seek a better life in western Canada but had remained in Ontario, close to Toronto, Vickers might have found it easier to begin his music studies and career. Yet his drive makes it impossible to conceive of his failing to follow his gift no matter where he might have found himself. And it is certain that the small-town associations and the eleven summers of farm work in his early days did much to nourish the artist he was to become.

His father, William Stewart Vickers, was born in Kirkton, Ontario, in 1890, the son of a Methodist carpenter and grain thrasher whose father had emigrated from England in the mid-nineteenth century. William had a grandmother of Irish heritage. A short, burly schoolteacher with a large head, William Vickers in 1914 married the petite sixteen-year-old Frances Myrle Mossip, known as Myrle (and in early records spelled Merle), the daughter of a dairyman from London Township, Middlesex County, Ontario. Bill Vickers (as his neighbors called him) first taught in Dryden, Ontario. The couple began having children almost immediately, and the young family moved west in 1920 to Melfort, Saskatchewan. Bill apparently had relatives in the area; his brothers also moved west. He taught and was town bandmaster until 1925, when he and Myrle settled in Prince Albert, some sixty miles northwest of Melfort. There, Bill became principal of the Connaught School. In 1941 he took over as principal of the King George School, a grade school attended by his children, and held that post till he retired in June 1956. He taught briefly after that at a Bible college in Three Hills, Alberta. He was also throughout his life a lay minister in the Presbyterian and Methodist traditions, which had a profound impact on his fourth son.

Jonathan was the sixth in a brood of eight blondly handsome children. His mother spoke of having two families because of the break of more than three years between her first five children and the last three. In that sense Jon was also an "oldest" child, with all the dominating aspects of that place in the birth order. Myrle's doctor told the couple that she should have no more children after her fifth was born in December 1922. Twenty-four years old at that time, she was small, four feet ten inches and ninety-two pounds. The doctor said, "This young woman's body has had enough, but it's not my decision."

Sterilization was suggested, but after Myrle and Will, as she and family members called her husband, had talked and prayed, they decided against it. "And the next one was you!" Myrle told Jonathan many years later, bursting into tears as she recounted the story to her son while on a plane trip.

Jon was born on October 29, 1926. Bernice was born in 1928, and Arthur Henry in 1932. Myrle also may have had a miscarriage after Arthur's birth. The older five were Frances Margaret; William David, known as David; John Wesley, known as Wesley; Albert Harvey, called Ab; and Ruth, the last two born in Melfort. The family recalled the children's birth order by a memory device: "Margaret Does Well At Reciting Jokes By Aristotle."

Bill Vickers was at band practice and Myrle Vickers was alone when Jonathan was born. "It was a very cold wintry night late in October. There was no running water or electricity in the old house, only a well in the backyard," Vickers told John Ardoin. That house was a yellow, two-story frame dwelling, probably at 1135 First Street East.

Myrle would say "she must have had a premonition that [Jon] was going into show business, because of the name she gave him," recalled a close family friend, Jean Anderson Turnbull. "Jonathan, instead of John. It just sounds showbiz." Blue-eyed Jonathan would grow to look much like his father, with a wide, strong chin, large-domed forehead, massive hands, and stocky build. Both had huge barrel chests and bowed legs. He described his father as "a steady, velvet-covered rock" and his mother as "a little bubbling bottle of champagne." They complemented one another to give the family "a magnificently happy home life," he said, and despite Bill's firm rule and their slim finances, this seems to have been the case.

Prince Albert was a city in which religion was important, as can be seen in its heavy vote in favor of Prohibition in 1916. It had been settled in 1866 by a Scots-born Presbyterian missionary from Ontario, who persevered even though he was not well received by the Cree Indians. Prince Albert's economic future would rest on the area's scenic beauties and on the lumber and agriculture industries that developed. The city had serious financial problems even before the 1929 crash and Great Depression, problems tempered somewhat by the opening in 1928 of the Prince Albert National Park, thirty-five miles north of the city, a major spur to employment.

So while the Vickers family had sturdy religious support in a setting of outdoor splendor--both strong influences on Jonathan--the depression years were devastating to the area. Jobless farmworkers flocked to Prince Albert, and in 1930 work camps were set up in the park. By 1939 the city had just over eleven thousand residents. Canada entered World War II that year, and one of several flight training schools was set up in Prince Albert; meanwhile, a number of Mennonite objectors worked in the park. The city was then on the road to growth and economic health.

But the 1930s were difficult for the Vickers family. They moved shortly after Jonathan's fourth birthday, in 1930, and in the depth of the depression, had to move again because they could not afford that home. He says that at that time his father went to work for a friend, "not so much to earn extra money as to ensure one less mouth at home to feed." Jonathan was just five in November 1931 when Bill's teaching salary was cut from $254 to $119.54 a month. But Jon remembered his father's dignity when he asked town officials for the right to farm a vacant lot adjoining his home. It became the Vickers vegetable garden: "My older brothers pulled up roots; all the sod was broken by hand," Vickers recalled. "I remember the happiness in that family when the harvest came in!" The lot was one of two adjoining the old frame house at 305 19th Street East, where Jon grew up. The Vickerses had three-quarters of the roomy two-story duplex, with fireplaces and a long veranda, and finally had modern utilities. Another resident lived in the back, and the other vacant lot was used as a maple-shaded play yard.

Myrle Vickers "never complained," recalled Eva Payne Furniss, a Prince Albert native and family neighbor. "She was hardworking and honest as the day was long. She would make all these breads, take huge loaves out of the oven. When she came to shucking peas, she'd do mountains of them [to put up for winter meals]. They had a small garden that ran into the next block.... And there were no wash machines then. She'd have lines full of clothes." As one might expect of a hardworking, religious homemaker with no money for luxuries, she never cut her hair and wore no makeup.

Jean Turnbull recalled, "I can remember the kids all having their chores. I would go home with Bubs [Bernice] after school, and there was always an apple in the pantry. The children all helped, setting the table and getting the vegetables ready" for dinner.

Myrle was a fastidious housekeeper, and the home had to be especially clean for Sundays. On Saturdays the Vickers children helped scrub, wax, and polish the floors while listening to the afternoon radio broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera, which had begun in 1931. Vickers specifically recalled the February 26, 1938, Aida at which Giovanni Martinelli became ill and collapsed halfway through "Celeste Aida," to be replaced by Frederick Jagel. Young Jon was eleven years old, and that season he also might have heard Richard Crooks as Des Grieux and Don Ottavio; Melchior doing heavy duty as Siegmund, Lohengrin, Parsifal, and Tristan; Martinelli as Otello; and René Maison as Don José.

Bill Vickers was a strict man; as Eva Furniss recalled, "he was a school principal. It went with the job." On occasion he could become angry with his own children. A dominant community figure, he expressed himself forcefully at teachers conventions, often on controversial subjects. If these became dinner table fodder at home, he clearly set an example for his brood. A former vice principal with Bill, H. A. Loucks, recalled at those conventions that "even if the majority failed to agree with him at first ... as often happened, he was able to convince his fellow teachers that he was in the right." This insistence on his views was a trait his son Jon would share.

William Powell, who went through school with Jon, recalled a winter day when they were in a group riding a homemade plank bobsled, racing dangerously down a hill near the Vickers home toward the railroad tracks, where the road curved. "Jon had difficulty sitting down next day in school. His dad gave him a blistering," although probably using just one big hand. Young Jon actually enjoyed the strictures of his life, but admitted later that "a couple [in the family] did rebel against it."

The family attended First Baptist Church, where Jon sang as a boy soprano and a sister later ran the Sunday school. Bill, although not ordained, filled in as preacher there, as well as at St. Paul's Presbyterian, particularly when it was between ministers, and at other area churches. "He had a tremendous voice, which I suppose he passed on to Jon, a bull voice. He would hold forth at great length," recalled John Victor Hicks, a Prince Albert resident who was an organist as well as an eminent poet. Bill kept a daily diary, knelt with his family to say grace at meals, and read the Bible through each year. He conducted Bible study sessions in a quite scholarly manner in his home as well as in churches. His favorite biblical book was Revelation, and he loved to talk of things to come as revealed there, perhaps imparting hints of life's mystery to some of his children.

"My father said the responsibility of a human being was to take whatever talent he has--whether to be a gardener or a president--and do that job to the utmost of his ability. That is the fundamental philosophy of my life," Vickers recalled. "Over and over again he would say, `You will do with your might what your hands find to do. You will do it to the best of your ability.' He pounded that into our heads; no matter what we did in this pursuit of excellence, we did it for the glory of God. I have never lost that."

Bill took his family on many preaching jobs with the Salvation Army, the Plymouth Brethren, and the United Church; the children would help provide music. Bill and Myrle played the piano, and Bill the horn in the city band. Myrle also had a pretty voice. The children played various instruments and all sang, both solo and in duos, trios, and quartets. This "poor man's Trapp family," as Vickers later called it, helped raise money for war bonds and for the Red Cross and was heard on local radio. "My first recollections of singing in public was when I was about five years old," said Vickers, then "a curly-haired little fella" who did some radio solos. The family sang at the jail and the Saskatchewan penitentiary. "I suppose it must have sounded pretty funny, but we gave pleasure," Vickers recalled. "I have a very clear memory of going into a prison on Mother's Day when I was six or seven" and the men whistling at his sisters. "I sang `Don't Forget the Promise Made to Mother' and couldn't understand why all the men were bawling." He also recalled a public Christmas concert in which he sang at age three.

His older brothers were in the city band and took music lessons, but Vickers never did, though he picked up a little piano playing. This, he said, was because his chief interest was singing. "I guess everyone thought of singing as a natural talent; you just opened your mouth and sang." Vickers claimed to have been extremely shy as a child, although this is not how others recall him. Singing, he said, was a way out of that shyness. But he added years later: "To begin with, I sang because I had to sing. It was part of me ... an absolute necessity, fulfilling some kind of emotional and even perhaps physical need in me."

When Jon sang as a teen at St. Paul's, the parishioners noted the tremendous size of his voice. The windows would rattle as he hit the final fortissimo of "Jerusalem" at full blast. Once, a visitor told the boy he had a remarkable voice and should be trained. His mother politely but firmly said, "No, Jonathan sings along with the rest of us." It was just a comment, but it became a seed of future conflict in her son as his interest in singing progressed. (Myrle never shortened his name to "Jon.")

The Vienna Boys' Choir passed through on a Canadian tour, and little Jon was introduced to its leader. "There were always people trying to push me. My mother and dad just pooh-poohed it.... I was just one of the family--and it's true, they were all very good singers." Indeed, his family later seemed to take his career somewhat casually; his sister Bernice, with whom he was close, never heard him sing at the Metropolitan Opera, though his parents did once.

Moviegoing was frowned upon, and there was no money for it anyway; card games were forbidden. But singing around the piano was a popular family pastime, with church friends and visiting servicemen joining the songs. "The piano bench never got cold," Vickers recalled. On Sundays only hymns could be played, and neighbors could hear the family in full voice.

Myrle was always ready to pack for a family picnic at Little Red River. Her older sons loved to tease her, and she enjoyed it all. A grade school friend of Jon's, Robert Motherwell, recalled rousing games of croquet on the big front lawn and a family that found lots of fun among themselves. Motherwell, who lived a few doors away, said there was always an extra chair at the Vickers dinner table, despite their skimpy budget. In return, he would sometimes use an extra nickel to take Jon to a matinee at the Orpheum, a western or a Flash Gordon serial. Jon's father, he thought, probably was unaware of those outings.

The Vickerses were far from the poorest family in Prince Albert, but "for a long time, I never thought that life was anything else but working to survive and eat," Vickers said. From ages eight to eighteen he worked every summer with his brothers on the farm of Frank White, in the Tisdale area. White was his father's best friend, and no one other than his father influenced him more, Vickers said. The young people always asked Jon to sing at get-togethers, White recalled. "He never hesitated, though I recall one time they accused him of showing off a bit, and so he said he wouldn't. But I went to him and asked, `Who gave you your voice anyway, Jonny?' `Well, God did,' he answered. `Then,' I said, `sing, sing, sing!' And he sang and kept on singing."

That farm was where the famed Vickers physique developed, based solidly on his genetic heritage from his father. He ran tractors, fed pigs, hauled water, cleaned chicken houses, brought in hay with horse teams, and worked with threshing crews. "I learned a love of the soil, and the sheer physical satisfaction of working against time and weather to plough the earth and prepare a crop. When you have experienced all these things in your most formative years, you can never take it out of yourself."

He usually returned a little late to the classroom each autumn "because they had to drag me off the farm to get me back in school." Helping with the harvest was encouraged in the war years. "They were some of the happiest days of my life," he said much later, recalling big country breakfasts with a happy crowd of workmen.

I realize my whole philosophy of life was formed in those years. In this rural setting I came to the conclusion the only meaningful thing in this life is contact with other human beings. It was there too that deep and profound Christian convictions settled in me which have been an influence all of my life.

The understanding, which slowly and surely developed in me, of the necessity of human contact and an understanding of the needs of others and their problems has probably, more than anything else, given me the ability to analyze my roles, to come to grips with a score, to study a drama, to project my feelings into the life of someone I've never met except on a piece of paper. It enabled me to put myself into that person's life and their feelings to the point that I can put the person on and wear him for my stage life.

He found more physical work at home: Bill Vickers would order fifteen cords of wood, which he and his sons would saw into sixteen-inch stove-length logs. For three springs Jonathan dug the garden of the Vickerses' next-door neighbor while her husband was overseas at war. The family had no car in the 1940s; Bill bicycled to his work at school and to make deliveries of Fleischmann's Yeast, a baking and medicinal staple that he sold to supplement his income. (He would have done well to make $5,500 annually at King George.) One of the boys, often Jon, would accompany him on his rounds. Even then Jon was spoken of as a lad with a good business head. He also worked after school at the local Safeway market.

The lawyer and budding politician John G. Diefenbaker was a family friend who also attended the Baptist church. At one point he offered to take in Jon to give Bill Vickers one less mouth at the table. The Vickerses appreciated the offer but "wouldn't hear of it," Vickers said later. Nevertheless, the Diefenbaker friendship was to endure until the future prime minister's death. The senior Vickerses themselves took in boarders after the older children left home; after 1946 they lived at 115 24th Street East (the 19th Street house has since been torn down).

Jon graduated in 1941 from King George, where his father had become principal that fall. (Jon may have begun grade school a year later than most because his father believed a child should be six before entering and Jon had an October birthday.) He then attended Prince Albert Collegiate Institute, a public high school. He was a high C or low B student but could have done much better had he not missed school on occasion because of his other jobs, recalled then-principal R. D. Kerr. "He was a smart boy ... with an analytical mind. He was nobody's fool, down to earth." At the time, the school was so crowded that it had morning and afternoon shifts. A shorter day gave Jon time to work, but Kerr had to talk with Jon about his absences.

The yearbook for his graduation year, 1945, listed "Johnnie `Look for the silver lining' Vickers" with the lines:

Our blond-haired tenor is always there With a merry laugh and never a care. He's willing to try out any new sport Is at home in the gym or basketball court.

He played football and basketball his senior year; the only school award he ever won, he said, was "most outstanding athlete" that year. He also did weightlifting, just for fun. He excelled in chin-ups and other school exercises, recalled Powell, and was very competitive on the basketball court. In the late afternoon Jon could often be seen striding down the street, smacking a softball into his glove, on the way to strike out a few more batters (but never on Sundays). John Hicks joked at the tribute more than three decades later that "had he but exercised a bit more singleness of purpose, he might have become one of the finest softball pitchers in northern Saskatchewan." Speed skating also became a Vickers favorite, with its dating, dramatic qualities, and he was urged to consider aiming for the Olympics.

Jean Turnbull recalled that Jon "was a real happy-go-lucky kid, very well liked. I can remember going ice skating with him down at the Minto Arena, and in those days ice skating was really something. That was one of the few things that your parents would let you do! They had one of those great big silver balls with mirrors on it that they use in ballrooms," turning with colored lights. Turnbull recalled visits when she was in third or fourth grade to the Vickers home, "playing hide-and-go-seek in that house ... with Arthur and Bubs [Bernice] and Jon. It was scary, because it was a big house." Jon was "a real teaser," far from shy. The high school students socialized as a group, so she never recalled his having a steady girlfriend. The Baptist church was very important in his life, and there was always a young people's group. They enjoyed cross-country skiing, sleighrides (after which Jon would sometimes sing), and swimming in the river. Vickers's IOA form teacher, Arnold Friesen, recalled him sitting in the back of the class, enjoying being surrounded by admiring girls.

Some pursuits were on a humble level. Vickers idolized his tall, handsome oldest brother, Dave, throughout his childhood, and recalled that Dave was a great player of "dibs." A dib was a small round piece of baked clay, "as opposed to those luxurious objects of childish wonder--glass marbles." Players bounced dibs off a wall, trying to land them within a handspan of another player's and thus win the other's dib. Dave won a total of one thousand dibs, and "I still recall the thrill when he staked all his little brothers to a hundred dibs apiece so that we could get going in that most exciting of games. How much more satisfying than to be given a dime to go and buy a hundred dibs!"

Vickers looked at his childhood poverty through the prism of the years in 1968 on a British radio program. He said that the sole object he would take to a desert island would be "a big, pretty child's ball." He had been given a rubber one for Christmas at age four or five: "I bounced it on a nail and it was destroyed." He recalled the incident vividly, "how sick this thing went in my hands." And his father "thought that I had broken it on purpose, and somehow I could not even have the courage to try to persuade him that I hadn't. I just accepted it."

The "it" referred to his father's stern judgment of his children. But the lesson later for Vickers was one of simplicity, a quality he would retain that served him well in his art. That ball reminded him "of the precious things that sometimes we can destroy without even thinking ... the simple, beautiful things of life, no matter how ordinary they may seem, they are very, very beautiful, that we should keep this childlike love of them, wonder of them, and as an adult protect and shield those things." Vickers had taken the interviewer's question more seriously than most guests would do. "You'll laugh when I tell you," he said, displaying the open, almost naive facet of his personality that was one of his most appealing traits.

That sternness of his father's left "an indelible imprint on my whole personality," Vickers later recalled. It made him uncompromising in his demands upon himself, and when he fails, "I feel I've let God down, I've let myself down, my profession down, my talent down. That's a natural product of my upbringing."

Jon had a seventh-grade music teacher, Nancy Larson, who gave many youngsters the joy of music. Robert Motherwell recalled that she particularly encouraged Jon, giving him solo parts and much instruction. "She had him picked as a winner." Her choirs always did well in town music festivals. At one, Jon's voice broke in the middle of the event. He was then about twelve years old.

The 1906 St. Paul's Church had been given a two-manual Casavant pipe organ in the 1930s. The church's organist, an Englishman named Luther Roberts, listened to young Jon sing "just after puberty," Vickers recalled. "He threw up his hands in horror and said this is too good a voice, you mustn't hurt it. He implanted in me perhaps too great a fear of hurting my voice." Roberts warned against trying to extend Vickers's range at his age. "He thought I was a baritone" because of the dark color of the boy's voice and its baritonal solidity in the lower registers. During his last year of high school Vickers took three or four months of vocal lessons with the organist. "He didn't profess to be a voice teacher, but he was a superb musician." Roberts kept the boy on pieces from oratorios-- Elijah was one, no doubt "Then shall the righteous shine forth," transposed down so his voice would not be strained.

And that, as Vickers put it, "was the very beginning of, how shall I say it--singling out of me from the rest of the family."

On the popular side, Vickers learned "Cherry Ripe," coached by John Hicks's wife, Marjorie, for an amateur concert at the Orpheum Theater. Marjorie also taught piano to his sister Bernice.

The Vickers family was in the audience when an evangelist appeared at St. Paul's. John Hicks played the organ for the event but doesn't recall what, if any, religious affiliation the man had. But the Vickerses thought he was wonderful, and the gospel-style music seemed to have had a strong effect on them. Hicks said, "If Jon hadn't moved [away], he could have become" an evangelist.

One autumn, in a Prince Albert Collegiate history class, the teacher, Arnold Friesen, asked students to talk about something that interested them. "I was fascinated with a little bit of Greek history ... the construction of the Acropolis," Vickers recalled.

But having never heard it pronounced before, I got up and made the marvelous mistake of pronouncing it the `Acro-PO-lis.' Everyone in the classroom howled with laughter, and I was reduced to falling into my shoes. And Mr. Friesen was marvelous the way he rescued me and made me feel reasonably comfortable.

Many years later I was invited to the Athens festival to sing in the Herodes Atticus, which is a great amphitheater in Athens. I was singing Otello, and it was quite an impressive sight. Princess Irene was in the front row. And as I stood and sang the opening bars, just on the horizon I saw the lighted Acropolis.

He laughed gently as he described the moment at his Prince Albert tribute. "It was quite, quite something."

Jonathan Vickers's road to the Greek monuments took him next to the music-loving Canadian towns where he got his first taste of the life onstage, a life that would consume him for almost forty years.

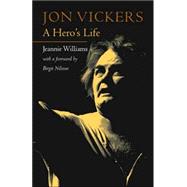

Copyright © 1999 Jeannie Williams. All rights reserved.