Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

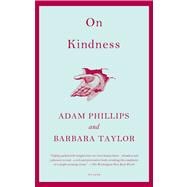

Adam Phillips is a psychoanalyst and the author of twelve books, all widely acclaimed, including On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored; Going Sane; and, most recently, Side Effects.

Barbara Taylor has published several highly regarded books on the history of feminism, including the award-winning Eve and the New Jerusalem.

She and Adam Phillips both live in London.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.