What is included with this book?

| INTRODUCTION "Somebody's Been Shot" | 1 | (13) | |

| PROLOGUE School of Hard. Knocks | 14 | (7) | |

| ONE Joey and the Angels | 21 | (12) | |

| TWO The Wild, Wild East | 33 | (11) | |

| THREE The Strange Case of Joe Jr. and Mr. Hyde | 44 | (8) | |

| FOUR Redbones | 52 | (7) | |

| FIVE It All Comes Home to Papa | 59 | (9) | |

| SIX The Seventh Basic Investigative Technique | 68 | (9) | |

| SEVEN God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen | 77 | (6) | |

| EIGHT The Halls of Montezuma | 83 | (13) | |

| NINE Slow Walking | 96 | (11) | |

| TEN The Confidence Man | 107 | (6) | |

| ELEVEN The Chief Gets His Hair Cut | 113 | (6) | |

| TWELVE Cold, Cold Heart | 119 | (5) | |

| THIRTEEN We Don't Need No Stinkin' Badges | 124 | (14) | |

| FOURTEEN The Gentleman from Milton | 138 | (11) | |

| FIFTEEN You Never Come Around Much Anymore | 149 | (9) | |

| SIXTEEN Cyrano de McCainiac | 158 | (10) | |

| SEVENTEEN Incident in Fall River | 168 | (11) | |

| EIGHTEEN The Return of Billy Dennett | 179 | (14) | |

| NINETEEN Appointment with Dr. Sommerov | 193 | (10) | |

| TWENTY Let Us Now Praise Famous Men | 203 | (14) | |

| TWENTY-ONE All You Need to Know | 217 | (14) | |

| TWENTY-TWO Hats on the Bed | 231 | (9) | |

| TWENTY-THREE Eddie Miami | 240 | (12) | |

| TWENTY-FOUR The Three-Hundred-Dollar Clowns | 252 | (16) | |

| TWENTY-FIVE One-fifty Gen-o | 268 | (15) | |

| TWENTY-SIX The Pride of the Mets | 283 | (7) | |

| TWENTY-SEVEN Flowers of Evil | 290 | (12) | |

| TWENTY-EIGHT The Third Man | 302 | (7) | |

| TWENTY-NINE Big Joe's Last Case | 309 | (9) | |

| THIRTY The Erin Society | 318 | (14) | |

| THIRTY-ONE The Punisher | 332 | (17) | |

| EPILOGUE "The Man Who Wasn't There" | 349 | (10) | |

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | 359 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

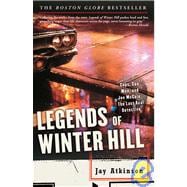

Excerpted from Legends of Winter Hill: Cops, con Men, and Joe Mccain, the Last Real Detective by Jay Atkinson

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.