|

3 | (116) | |||

|

|||||

|

119 | (166) | |||

|

285 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

For seven years there had been too little rain. The prairies were dust. Day after day, summer after summer, the scorching winds blew the dust and the sun was brassy in a yellow sky. Crop after crop failed. Again and again the barren land had to be mortgaged, for taxes and food and next year's seed. The agony of hope ended when there was no harvest and no more credit, no money to pay interest and taxes; the banker took the land. Then the bank failed.

In the seventh year a mysterious catastrophe occurred worldwide -- all banks failed. From coast to coast the factories shut down, and business ceased. This was a Panic.

It was not a depression. The year was 1893, when no one had heard of depressions. Everyone knew about Panics; there had been Panics in 1797, 1820, 1835, 1857, 1873. A Panic was nothing new to Grandpa, he had seen them before; this one was no worse than usual, he said, and nothing like as bad as the wartime. Now we were all safe in our beds, nobody was rampaging but Coxey's armies.*

All the way from California Coxey's Armies of Unemployed were seizing the railroad trains, jam-packing the cars and running them full speed, open throttle, hell-for-leather toward Washington. They came roaring into the towns, yelling "Justice for the Working Man!" and stopped and swarmed out, demanding plenty to eat and three days' rations to take with them, or they'd burn the town. People gave them everything to get rid of them. In all the cities Federal troops were guarding the Government's buildings.

I was seven years old and in the Second Reader at school but I had read the Third Reader and the Fourth, and Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver's Travels. The Chicago Inter-Ocean came every week and after the grown-ups had read it, I did. I did not understand all of it, but I read it.

It said that east of the Miss-issippi there were no trains on the railroad tracks. The dispatchers had dispatched every train to the faraway East to keep them safe from Coxey's Armies. So now the Armies were disbanded and walking on foot toward Washington, robbing and raiding and stealing and begging for food as they went.

For a long time I had been living with Grandpa and Grandma and the aunts in De Smet because nobody knew what would become of my father and mother. Only God knew. They had diff-theer-eeah; a hard word and dreadful. I did not know what it was exactly, only that it was big and black and it meant that I might never see my father and mother again.

Then my father, man-like, would not listen to reason and stay in bed. Grandma almost scolded about that, to the aunts. Bound and determined to get out and take care of the stock, he was. And for working too hard too soon, he was "stricken." Now he would be bed-ridden all his days, and what would Laura do, my family wondered. With me on her hands, besides.

But when I saw my father again he was walking, slowly. He limped through the rest of his ninety years and was never as strong as he had been, but he was walking.

We lived then in our own house in De Smet, away from Main Street, where only a footpath went through the short brown grasses. It was a big rented house and empty. Upstairs and down it was dark and full of stealthy little sounds at night, but then the lamp was lit in the kitchen, where we lived. Our cookstove and table and chairs were there; the bed was in an empty room and at bedtime my trundle bed was brought into the warmth from the cookstove. We were camping, my mother said; wasn't it fun? I knew she wanted me to say yes, so I did. To me, everything was simply what it was.

I was going to school while my father and mother worked. Reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, penmanship filled days almost unbearably happy with achievements satisfying Miss Barrows's strict standards. "Procrastination is the thief of time," I wrote twenty times in my penmanship book, without error or blot; and "Evil communications corrupt good manners," and "Sweet are the uses of adversity," every t and d exactly twice as tall as a vowel and every l exactly three times as tall; every t crossed; every i dotted.

All the way home down the long board walk in late afternoons we diligent scholars warmly remembered our adored Miss Barrows's grave, "Well done," and often we sang a rollicking song. It was the song of those days, heard more often than Ta-ra-ra boom-de-ay. My aunt Grace, a jolly big girl, often sang it, sometimes my mother did, and nearly all the time you could hear some man or boy whistling it.

O Dakota land, sweet Dakota land,

As on thy burning soil I stand

And look away across the plains

I wonder why it never rains,

Till Gabriel blows his trumpet sound

And says the rain has gone around.

We don't live here, we only stay

'Cause we're too poor to get away.

My mother did not have to go out to work; she was married, my father was the provider. He got a day's work here and there; he could drive a team, he could carpenter, or paint, or spell a storekeeper at dinner-time, and once he was on a jury, downtown. My mother and I slept at Grandma's then, every night; the jury was kept under lock and key and my father could not come home. But he got his keep and two dollars every day for five straight weeks and he brought back all that money.

My mother worked to save. She sewed at the dressmaker's from six o'clock to six o'clock every day but Sunday and then came home to get supper. I had peeled the potatoes thin and set the table. I was not allowed to touch the stove. One day my mother made sixty good firm buttonholes in one hour, sixty minutes; nobody else could work so well, so fast. And every day, six days a week, she earned a dollar.

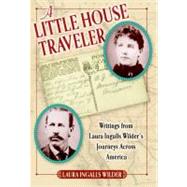

A Little House Traveler

Excerpted from A Little House Traveler: Writings from Laura Ingalls Wilder's Journeys Across America by Laura Ingalls Wilder

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.