| Acknowledgments Explanatory Note | |

| Introduction: The Epistolary Genre and the Scriptural Economy of the Choson | |

| Public Letters | |

| Royal Edicts: Constructing an Ethnopolitical Community | |

| Female Rulers: Queen Dowagers' Edicts and Letters | |

| Memorials to the Throne | |

| Joint Memorials: Scholars' Channel of Communication to the Throne | |

| Individual Petitions: Petitions by Women in the Choson | |

| Petitions by a Collective Body: A Petition by the Residents of the Chip'yong District | |

| Letters of Appeal | |

| Circular Letters in Choson Society: Writing to Publicize Opinions | |

| Open Letters: Patriotic Exhortations from the Imjin War | |

| Manifestos During the Hong Kyongnae Rebellion of 1812 | |

| Chon Pongjun's 1894 Tonghak Declaration | |

| Letters to the Editor: Women, Newspapers, and the Public Sphere in Turn-of-the Century Korea | |

| Letters to Colleagues and Friends | |

| Correspondence Between Scholars: Political Letters | |

| Scholarly Letters | |

| Friendship Between Men | |

| Friendship Between Women: One Man's Consorts | |

| Friendship with Foreigners | |

| Social Letters | |

| Letters of Greeting | |

| Letters on Everyday Life | |

| Male Concubinage: Notes on Late Choson Homosexuality by an American Naval AttachT | |

| Family Letters | |

| Letters Between Spouses | |

| Personal Royal Letters: Correspondence Between Monarchs and Their Children | |

| The Sunch'on Kims: Vignettes of Family Life Through Letters | |

| Fathers' Letters Concerning Their Children's Education | |

| Mothers' Letters of Instruction to Their Children | |

| Yi Ponghwan's Letters to His Mother During His Trip to Japan | |

| Daughters' Letters to Members of Their Natal Families | |

| Letters Written Away from Home | |

| Letters Written in Korean by Exiles | |

| A Letter Written in Literary Chinese by Chong Yagyong While in Exile | |

| Letters by Prisoners of the Imjin War | |

| Letters Sent Home by Royal Hostages | |

| Deathbed Letters | |

| A Letter Written Before Execution: A Condemned Man's Last Thoughts to His Children | |

| Letters of the Catholic Martyrs | |

| Madam Yi's Farewell Letter to Her Son | |

| Daughters' Letters of Farewell to Their Fathers | |

| Letters to the Dead | |

| A Wife's Letter to Her Deceased Husband | |

| Kwon Sangil's Farewell to His Deceased Wife | |

| Letters to Deceased Children | |

| Fictional Letters | |

| Love Letters in The Tale of Unyong | |

| Bibliography | |

| Index | |

| Table of Contents provided by Publisher. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

View this excerpt in pdf format | Copyright information

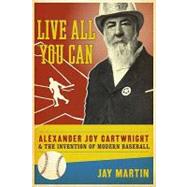

The Dream

Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr.'s dream was baseball. Like most boys and many girls in New York, Alick had grown up playing the varieties of ball games then current in the city. For young men, ball games were one of the city's chief entertainments in its mild weather from April through October. During summer, the extended hours of daylight allowed for games in the twilight after work. On the weekends, the entire day was at the disposal of the players, when games and family picnics could be combined. During the 1830s, ball games came to be organized into teams that revolved around civic organizations. Among these in New York were the various volunteer fire engine companies organized to fight frequent blazes. In a crowded city that had a large number of combustible wooden buildings, fire was an ever-present danger. The premier firefighting company was Oceana Hose Co. no. 36, which was reorganized in 1845 by Alick's brother Benjamin, who later became the first fire commissioner of New York City. Another fire company was Knickerbocker Engine Co. no. 12. Its engine and firefighting equipment were housed below Murray Hill, near Sunfish Pond, which the men used as their water source when they helped to fight the great House of Refuge fire of 1838. At this time, firefighting was done by volunteer assemblies. It was a public-spirited activity, though, to be sure, a large number of the volunteers sold fire insurance and thus had a special interest in fire-fighting. The presence of numerous fire companies created intense competition between the most able and agreeable young men. And this, in turn, led to considerable attention to the decorative splendor of the companies' costumes and pumping engines. The firemen splashily attired themselves in red shirts, high-crowned hats, black pantaloons, and heavy boots. At the first signal, they would rush to their engine house and wheel out their grand pumper, glistening with fresh paint and gleaming metals, and dash to the latest conflagration. Meanwhile, admiring and cheering crowds gathered to watch the incendiary battle.

To promote their activities and to finance the purchase of equipment, the fire companies marched in holiday parades and devised firemen's balls, contests, and award ceremonies. Naturally, too, members of individual companies of volunteers formed social relations in their neighborhoods. Just as naturally, the young men in them formed sports clubs. They rode horses or fished together, and, of course, they played ball games. Depending on the number of men present, they played versions of the traditional town-ball, one o' cat, or cricket with one another. At the earliest time, there was still no thought of competition on the field between fire companies or other organizations. Matches were club events, played by choosing sides among members. Engine Co. no. 12 had about forty members. About half of them showed up for any one game—plenty to make opposing sides.

We know that in the early 1840s, Alick and Alfred joined the Knickerbocker Engine Co. no. 12 and that in 1842 they and their fellow volunteers were playing "base-ball" wherever they could find a field in Manhattan. The lowest reaches of the island were beginning to be rather built up, but they still found plenty of expansive fields or vacant lots. There was a fine spot at Twenty-seventh Street, where the first Madison Square Gardens was later to be built. Sections of the parade ground that stretched west from Lexington Avenue between Twenty-third and Thirty-fourth Streets provided lots of open space. Forty-seventh and Fourth, where the first depot of the Harlem River Railroad was eventually built, was another good spot. So was the open meadow next to Sunfish Pond. Fields suitable for base-ball games were also likely to have a fine tavern nearby for conviviality. Social and family relations were an integral accompaniment of the game; part of the fun was in searching for fresh places of social festivity and athletic prowess.

By 1845, fire companies began to think of extending their competition in fighting fire to competition on the ball field. Alick was a leader on his team. At six feet, two inches, and 210 pounds, he was one of the strongest hitters and also a first-rate pitcher. Now he took the lead in organizing the team and the game it played. On September 13, 1845, he and Alfred were leading members of a team which they naturally named the "Knickerbockers Base Ball Club" after their fire company. Alex was the vice president and secretary of the club. In addition to the Cartwright brothers, the original organizers of the Knickerbockers were William R. Wheaton—a lawyer—Duncan F. Curry, Ebenezer R. Dupignac Jr., W. H. Tucker, and Jacob H. Anthony, an assistant cashier at the Bank of the State of New York. They were soon joined by Peter DeWitt, Abraham Tucker, Colonel James Lee, Dr. Franklin Ransom, James Fisher, and William Vail. Daniel Adams later recalled that the members of the club were "merchants, lawyers, Union Bank clerks, insurance clerks, and others who were at liberty after 3 o'clock in the afternoon." Many years later, in 1887, William Wheaton claimed that he had first codified baseball: "it was found necessary to reduce the rules of the new game to writing. This work fell to my hands, and the code I then formulated is substantially what is used today." Probably Wheaton, a Knickerbocker player, did assist in the discussion of an earlier set of rules or a later revision of the rules in 1848, but clearly it was Cartwright who put pen to paper and initially "formulated" them in 1845. For his team, Cartwright drew up a constitution, and the members agreed upon the by-laws which he recommended. In 1877, Duncan F. Curry stated definitely: "Baseball is an American game and owes its origin to Mr. Alexander J. Cartwright.... Well do I remember the afternoon when Alex Cartwright came up to the ball field with a new scheme for playing ball." He continues:

"The sun shone beautifully, never do I remember noting its beams fall with a more sweet and mellow radiance than on that particular Spring day. For several years it had been our habit to casually assemble on a plot of land where the Harlem Railroad Depot afterward stood. We would take our bats and balls and play any sort of game. We had no particular name for it. Sometimes we batted the ball to one another or sometimes played one o' cat.

On this afternoon I have already mentioned, Cartwright came to the field—the march of improvement had driven us further north and we located on a piece of property on the slope of Murray Hill, between the railroad cut and Third avenue—with his plans drawn up on a paper. He had arranged for two nines, the ins and outs. That is, while one set of players were taking their turn at bat the other side was placed in their respective positions on the field. He had laid out a diamond-shaped field, with canvas bags filled with sand or sawdust for bases at three of the points and an iron plate for the home base. He had arranged for a catcher, a pitcher, three basemen, a short fielder, and three outfielders. His plan met with much good natured derision, but he was so persistent in having us try his new game that we finally consented more to humor him than with any thought of it becoming a reality.

At that time none of us had any experience in that style of play and as there were no rules for playing the game, we had to do the best we could under the circumstances, aided by Cartwright's judgment. The man who could pitch the speediest ball with the most accuracy was the one selected to do the pitching. But I am getting ahead of my story. When we saw what a great game Cartwright had given us, and as his suggestion for forming a club to play it met with our approval, we set about it to organize a club."

Curry's statement was supported by a famous early baseball player, George Wright, who wrote, "In the Spring of 1845, Mr. Alex J. Cartwright, who had become an enthusiast in the game, one day upon the field proposed a regular organization" of the Knickerbockers' game. Cartwright wrote the rules down in a little five-inch by three-and-a-half-inch black book that he took from his stationery shop. On the cover in gold letters, he stamped "Knickerbockers." Dues for players were set at five dollars per year. Dressed in the newly fashioned team uniform of straw bowlers, sporty flannel shirts and vests, blue pantaloons and jackets, six of the organizers went to have their photo taken. Alfred and Alick draped their arms around each other in the back row, and one of the sitting players stuck a cigar in his mouth at a rakish angle, mugging for the camera.

The Knickerbocker charter put stress upon the social character of ballplaying and the social status of ballplayers. Article V emphasized that members of the team should be held to high standards of personal behavior. Players, it stated, should not use "profane or improper" language. Were any caught doing so, a fine of six and a quarter cents could be levied for each infraction. Improperly disputing with an umpire could cause the basic fine to be doubled. Abuse of the team captain would bring an immense fifty-cent penalty. Baseballers were to be American gentleman. No wonder that the baseball historian Harold Seymour referred to Cartwright's Knickerbockers as a "social club with a distinctly exclusive flavor."

The club rules were formed. The team was named. All that remained was to state precisely what rules of play would prevail if games among Knickerbockers and eventually against other teams were to be and mean anything but fun and frolic. After all, if it was to be a gentleman's game, and not just the rowdy pastime of English and American children, it would have to be regulated and organized. As the early baseball historian William Cauldwell noted in 1905, the boys' game before 1845 "had no regular form or shape... until the formation of the Knickerbockers Club, when boys of a larger growth took the matter in hand." Baseball was henceforth to be a regulated and refined game. Baseball, no less than American social life, was to be guided by the rule of law and Victorian etiquette.

Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr. invented baseball in 1845. This was an age of invention, and Cartwright became one of its great inventors. Base-ball, rounders, and town-ball retreated into the past. A new, distinctively American game was assembled. It did not derive from the traditions of Europe but rather was invented through the practical, enlightened thinking that had created the union of the United States, whereby uniform national laws became standard everywhere and at every time. The quest in America for a national identity had extended from its roots in revolutionary politics and social egalitarianism to a national capitol and a national flag and a national bird and national arts. Now it went all the way to baseball as the national game.

Baseball meant bases. Cartwright designated that a "base" would not be a stake or a rock merely meant to mark progress around the field to home but a place where the runner could stand—a flat base. This made the next step possible, as Cartwright went about designing baseball as an engineer designs a machine, as Fulton designed the steamboat Clermont in 1807 or Eli Whitney the cotton gin. The parts had to fall together. With bases it became possible to eliminate the most strained and unruly part of the game—"plugging" a runner with the ball to make him out. Now, if the ball arrived at first base before the runner, he was "out." He didn't have to be hit with the ball. This meant, too, that at the other bases a runner could be "forced out." The outlawing of plugging a runner to make him out also allowed the ball to become harder and allowed hits for much greater distances. We still have balls used by the Knickerbockers. These weigh about ten and a half ounces and have a rubber center that was wrapped in yarn, then covered in leather. With a harder ball, the pitcher had to be moved further than a few feet from the batter to prevent injury. Cartwright moved the pitcher to forty-five feet from home plate. At that distance, then, the gentle underhand toss to the batter's favorite spot would no longer be possible. The pitcher had to throw fast, in an effort to make the batter strike out. At first pitches were thrown underhand with a stiff arm, but eventually it was inevitable that overhand delivery would become common. Then the pitcher could be moved still further from the batter. With a faster pitch, strikeouts would become more frequent. Cartwright designated that three strikes would make an out. But in the constitutional spirit of checks and balances, he also created the "walk," obliging the pitcher to deliver the ball over the plate, or else "walk" the batter to first. The bats used by the Knickerbockers measured two and a quarter inches in diameter and could be any length and weight.

But how was the field to be designed? The rectangular field of play in rounders or the multidirectional field of cricket allowed batters to hit in all directions, sometimes far from the bases, so that the new concept of force-outs wouldn't work easily. And the variable distances between home and first, first and second, second and third, and third and home, initially gave advantage to the runner and then to the fielders as the batter attempted to round third and make home. This was not symmetrical, ordered. Cartwright solved these two problems at once by making the field of play square, turning it ninety degrees to make a diamond, and demanding that "fair" balls must be hit forward within the extension of the lines of the diamond into the outfield. Years later, Cartwright reminded Charles Deborst that the first diamond-shaped field was on "the pleasant field of Hoboken in New Jersey, the Elysian Fields,... where... most of the early games were played." Indeed, according to Frank Borsky, it was Cartwright himself who laid out the first baseball diamond at Elysian Fields. But how far apart should these bases be? Here, more than in any other decision, Cartwright showed off his inventiveness, in accord with the scientific, mechanical focus of his time. If the bases were placed, say, sixty feet apart, the runner would have an immense advantage. He would almost always beat a throw. Contrariwise, if the base paths were a hundred and twenty feet from one to another, few runners would arrive safely. Cartwright studied the actual activities in a ball game so as to achieve equality of advantage between runners and fielders. At ninety feet (or thirty paces) between bases, the ball and the runner would arrive at nearly the same time. Ninety feet it would be.

In 1947, Alick's grandson, Bruce Cartwright Jr. spoke to a journalist about his early memories:

"When I was a small boy it was my great joy to hear grandpa tell about the early days of baseball in New York.... Grandpa, having an inventive mind, decided to improve [town-ball]... by framing rules, including the definitions and dimensions of the playing field. So, one day Alex and his teammates decided to lay out a diamond. First, he placed a piece of wooden board to represent 'home,' then walked thirty paces [at 3 feet per pace] toward first base, designating the point with a sand bag. For each succeeding base he stepped off another thirty paces in a line at a right angle to the preceding one, thus forming a square....

'You know,' said Mr. [Bruce] Cartwright with modest pride, it is one hundred years since the first regular game was played by the Knickerbockers... but the size of the original diamond has remained unchanged."

In town-ball or rounders, the side would not be "out" until the entire team of players had batted. This made for a slow game, but Americans adored speed. Cartwright designated three "outs" as retiring the side. Victory in many earlier ball games was achieved by the first team to reach twenty-one runs, on the condition that both teams had had equal turns at bat. But with a mere three outs required to retire a side, and with force-outs and strikeouts, many hours might be required before any team would reach twenty-one. With the logic of mathematical deduction, Cartwright determined that three outs would make an "inning" (when one team was "in") and three or more innings would constitute a game, whatever the score. The same mathematical precision came to apply to the number of players. With the field of play confined to the enclosure of the "foul lines," fewer players were needed to cover the field. Cartwright reduced the two catchers behind the plate in town-ball to one, since batters could not hit fair balls backward. With three infield bases to be covered, he placed one fielder at each base. The many players who previously stood helter-skelter behind the infielders were eliminated and reduced to three outfielders, similar to the three infielders. Then Cartwright (or perhaps Adams with Cartwright) inserted a "shortstop" who could roam between infield bases and relay throws from the outfield. (We know that Daniel Lucius Adams played shortstop in the first recorded game.) Cartwright counted these positions and, with the pitcher included, arrived at the magic number of nine players.

Just over three weeks after the Knickerbockers drew up their by-laws and rules, they played the first game under the new regulations on October 6, 1845. From his stationer's shop Cartwright brought along a new scorebook in which the games could be recorded with regard to "Names," "Hands Out," "Runs," and "Remarks." Places for the date and name of the umpire were also designated. After all, with the new rules making much more intricate play, the umpire increased in importance. If the batter was like the president and the fielders like the Congress, the umpire was the Supreme Court. In Cartwright's famous rules the umpire was so described: "All disputes and differences relative to the game, to be decided by the Umpire, from which there is no appeal." Fines were levied freely for protesting the umpire's "calls." Cartwright himself got a double fine of twelve cents in October for too vigorously "disputing the umpire." In his own hand Cartwright recorded the results of this first game.

That Cartwright was the team's best hitter is clearly signaled by the scorebook, for he was the first batter to come to the plate in this first display of modern baseball. After all the preparations made for the new game, this first moment was anticlimactic. Cartwright made an out. One down. James Moncrief batted next. Two outs. Peter DeWitt came to the plate. Out. The side was retired in order. The opposing side came up. Duncan Curry made an out. Then, finally, Fraley Neibuhr made the first hit under modern baseball rules. Maltby followed with another hit. The next batter, Dupignac, was out, but Turney and Clare both reached base before Gourlie made the third out to end the first inning.

Cartwright's team caught life in the second. Tucker, Birney, and Moorhead all reached base, while Smith made the first out. Then Cartwright and Moncrief failed again.

Curry's team came up. Niebuhr got a second straight hit and so did Maltby. Dupignac hit safely. Then Turney made the first out. Clare and Gourlie made hits. This brought Curry up, but he failed to reach base. Niehbuhr and Maltby both hit safely, and so did Clare. Then Curry made the third out.

Cartwright's team started well in the top of the third inning, with hits by DeWitt and Tucker before Smith again made the first out. Moorhead followed with an out. Cartwright came to bat and finally made his first hit. Moncrief also got on base for the first time. So did DeWitt, Tucker, Smith and Birney, but Moorhead made his second out of the inning and the rally was crushed.

The end of the third inning would bring the game to a close. Neibuhr was finally stopped. Out number one. Maltby, Dupignac, and Turney hit safely before Clare made the second out. Gourlie followed and reached base. So did Curry—finally—and Neibuhr. But Maltby ended the game.

After both sides had batted three times, this first practice game was called. Curry's team had scored eleven runs, while Cartwright, though the "Father of Baseball," led the first losing team, with a total of eight runners reaching home. Alick contributed one hit and one run. (However, in a later game recorded in the scorebook, Cartwright, batting second, redeemed his reputation by having a perfect day at the plate and leading his team in runs scored with five. His team won that day, twenty-eight to twenty-seven.) To be sure, not all the new rules were adhered to in the first intrasquad game. Only fourteen players arrived at the Elysian Fields, near Hoboken, New Jersey, so seven players made each side.

In the fall of 1845, New York had an Indian summer. The weather stayed fair, and with their woolen uniforms the Knickerbockers were able to play every Thursday or Friday afternoon between October 6 and October 18, with eighteen or more players showing up for subsequent games. All the statistics were duly recorded by Cartwright in his scorebook. From the first, baseball was closely associated with accounting and records. Primarily the Knickerbockers games were played by sides chosen from members of the club. One historian conjectured that "they strived to be sole proprietors of the new sport."

"A friendly match of the time-honored game of Base was played at Elysian Fields," on October 21, 1845, the New York News reported. Baseball was expanding rapidly. Other independent teams were being formed. It appears that on this occasion Cartwright's New York Knickerbockers were challenged to a "friendly match" by a team of Brooklynites. Cartwright's team won twenty-four to four, aided by the first recorded "grand slam," a "four aces" home run with the bases loaded. Still, Brooklyn was not willing to concede preeminence in baseball to New York, and the News reported that "two more Base clubs are already formed in our sister city Brooklyn, and the coming season may witness some extra sport." Indeed, the paper reported that the Brooklyn team had already agreed to a rematch with the Knickerbockers on October 24 and that this game would be decided by the team that achieved "the first 21 aces or runs." One of the Knickerbocker players, E. A. Ebbets, had close associations with Brooklyn and was a relative of the man who would later found Ebbets Field.

After the Knickerbockers had played fourteen recorded games during the fall of 1845, cold weather brought a recess. But as soon as warm weather returned, on April 10, 1846, the beginning of the Easter holiday, the Knickerbockers resumed play. Cartwright headed his scorebook grandly with the date and the notation "Commencement of the Season." The score on opening day was forty to thirty-five. By June 19, the Knickerbockers had played seventeen practice games among themselves. Alick's brother, Alfred de Forest Cartwright, played in and umpired some games. So did his brother-in-law (married to Kate), George D. Cassio. Now they were ready to form what was to become the next moment in the expansion of baseball.

Two separate teams were to play each other, the Knickerbockers against the "New York Nine." At the head of the scorebook, a Knickerbocker player titled it the "1st Match Game," featuring the "Knickerbocker Baseball Club" versus "New York." Certainly, it was not the first match game, for that had been played the previous season against a Brooklyn team. But it is the first match game for which we have a scorecard, the first historically documented game between two somewhat distinct teams. According to one contemporaneous observer, this historic match game was "played under perfect skies as lady visitors sat under a canvas pavilion to protect their alabaster complexions from the sun." It was played at Elysian Fields. Duncan F. Curry described this "first" match game on June 19:

"'Well do I remember that game,' continued Mr. Curry, the first regular game of baseball ever played hereabouts, and the New Yorks won it by a score of 23 to 1. An awful beating you would say at our own game, but, you see, the majority of the New York Club's players were cricketers, and clever ones at that game, and their batting was the feature of their work. The chief trouble was that we had held our opponents too cheaply and few of us had practiced prior to the contest, thinking that we knew more about the game than they did. It was not without misgivings that some of the members looked forward to this match, but we pooh-poohed at their apprehensions, and would not believe it possible that we could lose. When the day finally came, the weather was everything that could be desired, but intensely warm, [and] yet there was quite a gathering of friends of the two clubs present to witness the match. The pitcher of the New York nine was a cricket bowler of some note, and while one could use only the straight arm delivery he could pitch an awfully speedy ball. The game was in a crude state. No balls were called on the pitcher and that was a great advantage to him, and when he did get them over the plate they came in so fast our batsmen could not see them."

Jerry R. Erikson has reproduced the "Diagram" of the baseball field made by Alexander Cartwright in late 1845 and regularly introduced for practice sessions in the spring of 1846. This was the field for the first recorded match game. Erikson writes:

"Players voted in favor of it, and the playing field for the first game between organized clubs was marked off according to this diagram, with the pitching distance at 45 feet.... Since then the only changes in arrangement by Cartwright are that shortstop now plays back of the baseline, catcher plays closer to the plate, positions of umpire and scorer have shifted, and plate has been moved back into the corner of the triangle."

The final score of this "match game" was twenty-three to one. Internal evidence suggests, however, that the New York Nine team consisted of sometime Knickerbocker players. The scorebook actually first listed the "New York" players under K.B.C. (Knickerbocker Baseball Club), then someone crossed this out and designated the team as "New York." Players who had been in previous lineups at Elysian Fields games, such as William Tucker, Daniel Adams, and Jacob Anthony, were in the lineup under "Knickerbocker Baseball Club," while Doctor Franklin Ransom, an original Knickerbocker and a member of the medical society of New York, was in the lineup for New York. The "1st Match Game," it appears, was between the original Knickerbockers who stayed in New York to play and those who now made Elysian Fields their "home." Cartwright umpired this game and fined the Wall Street broker James Whyte Davis a nominal six cents for swearing at him after a disputed call.

This game is part of history as well as legend. It has been certified in the law. In 1972, in writing the Supreme Court majority holding in Flood v. Kuhn (407 U.S. 258), Associate Justice Harry Blackmun began the opinion of the Court: "It is a century and a quarter since the New York Nine defeated the Knickerbocers 23-1 on Hoboken's Elysian Fields, June 19, 1846, with Alexander Jay [sic] Cartwright as the instigator and the umpire. The teams were amateur, but the contest marked a significant date in baseball's beginnings. That early game led ultimately to the development of professional baseball and its tightly organized structure." Blackmun termed baseball "the 'national pastime.'"

Elysian Fields had several advantages. First, it was located on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, with such scenic beauty that it was here that the "Hudson River School" of painters flourished, the first important group of artists depicting America's natural wonders. Second, it was easy to get there. The players would walk together down to the ferry terminal at Barclay Street and pay thirteen cents for a round-trip fare on the Stevens Hoboken Ferry. Once on the Jersey side, a short walk from the terminal following the river up Hudson Street brought them to a broad field surrounded by undergrowth and woods on three sides and, on the cleared side, taverns, such as the McCarty Hotel, where it is recorded that the team ate, once buying thirty dinners at $1.50 each. Many New York residents took Colonel John Stevens's ferry over to this resort area to spend a day in the open. The players had a built-in audience of picnickers here, along with drinking establishments where they might quench their thirst or get a bite to eat. Elysian Fields was, as William A. Mann writes, "one of the most popular outdoor recreational places in the New York metropolitan area. It was a perfect site for ball games." Sometimes refreshments were delayed until the players had crossed back to the Manhattan side after the conclusion of a game. In the Fijux Hotel, near the Barclay Street ferry, at number 11 Barclay, the Knickerbockers would sometimes continue the day's fun, review their individual efforts, and debate the progress of the new game, all the while choosing and sampling further refreshments.

In Cartwright's scorebook a record was kept in his own hand as to his personal performance from 1845, when the Knickerbockers were organized, to his departure from New York for the West. He recorded that he played in 121 games, scored 448 runs, and was retired 354 times.

Club teams, rules, enthusiastic and partisan fans, an open grassy meadow, a "home field," the excitement of the competition, the summer sun, eating snacks and drinking beer... the national game of baseball had been born. In 1846 a perceptive New York journalist named Walt Whitman noticed baseball. Very likely he had seen Cartwright play. He wrote: "I see great things in baseball. It is our game—the American game. It will take our people out-of-doors, fill them with oxygen, give them a larger physical stoicism. Tend to relieve us of being a nervous, dyspeptic set. Repair those losses and be a blessing to us." Ten years later Whitman would publish the first edition of Leaves of Grass and begin to reinvent himself as America's national poet. But in 1846 he saw at the very outset what was already destined to be the national sport, Cartwright's invention. On several later occasions Whitman spoke of the healthy physical development that baseball playing could bring, reflecting the insistence in Cartwright's charter and by-laws for the Knickerbocker team that they sought "the attainment of healthful recreation" in baseball.

Cartwright and his Knickerbocker teammates came at a dramatic time in the history of the burgeoning new nation. In the early nineteenth century, the calls to fashion a distinctive American culture were heard everywhere in the land. Americans had proved themselves powerful enough to defeat England for a second time in the War of 1812. Europe—old Europe—as many people were saying, had been left behind, abandoned. Waves of immigrants were departing from its ports daily to flock to American shores. The United States was a new presence on the world stage. To its citizens a unique epoch in world history was being inaugurated in North America, and therefore everything about Americans should be different. Most Americans and such transplanted Europeans as Crevecoeur believed that this new character should be manifested everywhere. In this spirit, John Montgomery Ward, himself a star player for the New York Giants, later wrote in his book Base-ball: How to Be a Player, that baseball was the athletic equivalent of the American democratic system of government, for while "it has doubtless been affected by foreign associations, it is nonetheless distinctively our own."

Americans in the early republic relished multiplicity, variety, novelty, difference, experiment, invention. Equally, they cherished the rule of law. Both were embodied in their newly adopted federal Constitution. At the end of the 1830s, base-ball exemplified the first tendency. It had nearly an unending multiplicity. It was indeterminate, always new, an experiment in what would work. It was like the frontier, a daily invention, lawless. It might have stayed that way—and in some sense, it has. Stickball, with a pink rubber "spaldeen" or a tennis ball and a strike zone chalked upon a wall; "whiffle ball"; tennis-racquet ball, using city street sewers as markers; balls pitched and slapped with an open hand—these are some of the descendents of the unregulated variety of the ball games existing in 1830s and 1840s. But with adult teams forming, challenges made, and championships to be determined, some sort of rule of common law would be needed, unless ball was destined to remain a pick-up game played mostly by children. Madison, Hamilton, and Jay had ably defended a Constitution that could apply uniformly to the thirteen states. But no equivalent constitution had yet appeared to turn base-ball into baseball. A new, national political system had been invented on native shores. A distinctive American literature was being shaped in the 1830s and 1840s by Emerson, Cooper, Poe, Irving, Hawthorne, and Melville. A national bank had been created. Crevecoeur, James Fenimore Cooper, George Bancroft, and many other commentators were claiming that in America a "new man" was being fashioned. Sports of all kinds were thriving everywhere, but no distinctive national sport had emerged. The American landscape, with its extensive open spaces, seemed likely to make ball games the best candidate for a national sport. What other country in the world so proliferated with such a plentitude of untouched land open to the public—commons, meadows, plains—fields of dreams?

"Elysian Fields"—the very name spoke of dreams. There, in 1845 Alexander Joy Cartwright Jr. laid out a field and stamped rules upon it. Decades later this particular field was paved over by modern progress, but the game remained and grew until it was played nearly everywhere in the world.

The first grand sign of its universality came when baseball was brought around the world by Spalding's tour in 1888 and 1889. Many foreign journalists commented positively on the muscular development and the speed of the players, but most of all, they noticed the Americanness of the game. The nation had a national sport that would in time bid to be an international one, just like the nation in which it flourished.

***

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Published by Columbia University Press and copyrighted © 2009 Columbia University Press. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. For more information, please e-mail or visit the permissions page on our Web site.