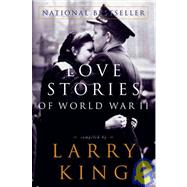

Larry King tells the stories of these love affairs just as the couples recalled them, capturing the special feeling of those times in their own words. The stories are complemented by a wealth of personal photographs and reproductions of touching memorabilia, including V-mail letters, newspaper accounts, and even the ticket stub from a movie seen on a first date.