Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

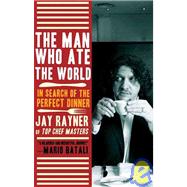

Looking to rent a book? Rent The Man Who Ate the World In Search of the Perfect Dinner [ISBN: 9780805090239] for the semester, quarter, and short term or search our site for other textbooks by Rayner, Jay. Renting a textbook can save you up to 90% from the cost of buying.

Jay Rayner is the restaurant critic for the London Observer, a regular contributor to Gourmet, and has written for both Saveur and Food & Wine in the United States. He has also written novels, most recently The Oyster House Siege. Rayner began his acclaimed journalism career covering crime, politics, cinema, and theater, winning Young Journalist of the Year in 1991 and Critic of the Year in 2006 at the British Press Awards.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.