| Introduction | xi | ||||

|

|||||

|

6 | (16) | |||

|

22 | (28) | |||

|

50 | (20) | |||

|

70 | (36) | |||

|

106 | (48) | |||

|

|||||

|

154 | (42) | |||

|

196 | (38) | |||

|

234 | (35) | |||

|

|||||

|

269 | (32) | |||

|

301 | (34) | |||

|

335 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

She's seated on her throne in the school gymnasium, a bouquet of roses in her arms and a pageant banner draped across her dress. The principal, a Troy Donahue look-alike, is adjusting a dainty silver crown on her head. It's 1959, and fourteen-year-old Basilia Jesus Martinez, whom everyone calls Bessie, looks sweet and pretty in her white-chiffon hoopskirt, the crinoline made of tulle -- a dressier outfit than the one she'll wear in two years when she rushes to marry my father. Voted the "Tower Queen" of D. W. Griffith Junior High School in East Los Angeles, she is, according to her friends, the Mexican-American version of the popular Mouseketeer Annette Funicello. But the photographer has caught her at an unexpected moment, when she looks more uncomfortable than pleased. Her look communicates misunderstanding -- the sudden flash was a bad augur -- as if even she, with her cheery optimism and sentimental faith in the world, senses the farce: she, with her dark, full, Indian face, as a symbol of contest beauty in Sandra Dee's bobby-sock America.

My father, Joey, her escort, stands next to her, weighing a little less than a hundred pounds. He's wearing a dressy black jacket, a white shirt, and a tie with clip. His arms are in front of him, his left hand clasped over the hand of his polio-withered right arm. Despite his small stature, he has a dangerous reputation. There are rumors that he once beat a boy with a baseball bat. He is a member of the neighborhood gang El Lote Mara ("The Lot"), considered by some to be the oldest gang in Los Angeles. In the photo his head is erect, as if he is staring over the heads of a crowd we cannot see. He's intentionally not smiling, either to act tough or to hide the gap between his two big front teeth, or both. The pursed lips and the head that is slightly cocked back are the juvenile pose of the pachuco -- a pose that I, too, would eventually assume.

This yearbook photograph is the earliest evidence of my parents' courtship.

Scribbled on the inside flap of my father's Tower yearbook that year is my eighth-grade mother's sworn affection for him:

Honey, I don't have very much to say but that it was very nice sharing a lot of things with you. (You know what.) Don't ever forget every thing we had in school because I won't. Hope to see you in all my periods at Garfield. Don't forget I will always love you. Yours always, Bessie p.s. Love always and always and always.A religious movement burned through the Maravilla housing projects in the mid-1950s, halcyon days for the hallowed East Los Angeles elect, when the young evangelist Billy Graham's altar call from mid-field ignited the jam-packed football stadium at the nearby community college. (My father's mother, Nellie, was one of thousands who rose in the bleachers in response to the call to surrender her soul to Christ.)

A few miles away, in downtown L.A., Pastor J. Vernon McGee of the Church of the Open Door (or C.O.D.) encouraged Ruth Burke to use the Maravilla housing projects as her mission site -- two missionary boards had denied her a post in Japan -- since she had already started a chummy evangelical Bible study group there known as the Good News Bible Club.

Ruth Burke was born in Palestine, Texas. She had come to Los Angeles to attend Biola College, whose campus in those days was the Church of the Open Door. Heeding her pastor's advice, she moved into a storefront across the street from the projects.

With a sweater worn across the back of her shoulders like a cape, Ruth walked around the neighborhood knocking on doors, distributing pamphlets, and asking parents if their children could come to her Good News Bible Club.

In the Good News Bible Club, Ruth preached a personal and Protestant relationship with the Bible. Each child was awarded a Bible for attending the club. A child first learned the order of all sixty-six books in the Bible through an easy-to-remember, Sesame Street sort of sing-along song. Then they'd play "Bible drill": Ruth would shout out a verse, such as John 3:16, and the older kids would race to locate it. The winner would then read it aloud. The younger kids, who couldn't read, merely pretended to know what they were doing as they flipped through the Bible's pages. They were being trained, nonetheless: they would know the Bible themselves and not need to rely upon the interpretation of Catholic priests.

Very few Protestant churches in East Los Angeles at the time preached in English, so the candies Ruth offered weren't the only incentive to attend the club. Mexican immigrant parents sent their children to her club to learn English.

Soon the neighborhood mothers invited Ruth to their homes, telling her she was too skinny and plying her with tamales and Mexican sweet bread. At the end of her day, Ruth could be seen walking home carrying homemade tortillas wrapped in a scarf, a gift from one of the grateful women of Maravilla. Ruth Burke, the Irish Protestant who converted Mexican Catholic families, became a sort of honorary barrio mascot.

My mother was a sophomore in high school when she got pregnant with me. Her father, my grandpa Nieves, was a gentle man and he wouldn't be upset, she thought. But her father didn't live at home anymore, so it was her mother, Frances, she really worried about. My mother and my father swore not to tell anyone their secret. But my mother soon confided in my aunt Maggie, her older sister closest in age.

Unfortunately, as protective as Maggie generally was, she reacted badly to the news. Maggie didn't like my dad, whom she considered a little punk, an insecure boyfriend, and an altogether unsafe bet as a boyfriend. Maggie had seen Bessie cry, deeply remorseful after Joey berated her for something as innocuous as talking to another boy after school.

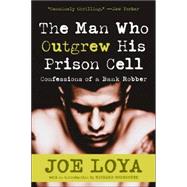

The Man Who Outgrew His Prison Cell

Excerpted from The Man Who Outgrew His Prison Cell: Confessions of a Bank Robber by Joe Loya

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.