Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

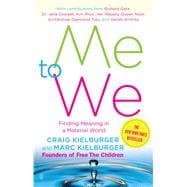

Looking to rent a book? Rent Me to We Finding Meaning in a Material World [ISBN: 9780743294515] for the semester, quarter, and short term or search our site for other textbooks by Kielburger, Craig; Kielburger, Marc. Renting a textbook can save you up to 90% from the cost of buying.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

We respectfully disagree. Not only do simple answers to life's burning questions exist, but we've learned that those that often appear most obvious can be profoundly life-changing. What's more, in our travels far and wide we've learned that the solutions to life's challenges both large and small can be found at every turn both here in North America and around the world. They are simply waiting to be recognized.

What are we talking about?

A life philosophy called Me to We, a way of living that feeds the positive in the world -- one action, one act of faith, one small step at a time. Living Me to We has the potential to revolutionize kindness, redefine happiness and success, and rekindle community bonds powerful enough to change your life and the lives of everyone around you.

You may think we are rather young to be writing a book like this. You may also wonder what business two ordinary brothers from a middle-class suburban neighborhood have extolling the virtues of an idea as powerful as this one. But the Me to We philosophy does not belong to us. It belongs to you, and to all the others we've been blessed to meet through our extraordinary life experiences.

Over the past decade we have had the chance to spend time in more than forty countries meeting with people from all walks of life. We have come to know some of the greatest spiritual, political, and social leaders of our time, and have been fortunate to learn from luminaries like the Dalai Lama, Nelson Mandela, and Pope John Paul II. Countless others have inspired us with the beauty of their vision, the strength of their commitment, and the significance of their actions.

Along the way we have shared simple meals of rice and roti with people struggling in the slums of Calcutta and attended opulent banquets with some of the world's most powerful business moguls at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. In the war-torn villages of Sierra Leone, we've had discussions with people whose limbs were savagely amputated by armed militias, and at major United Nations conferences we've sat on panels with heads of state and royalty.

We've spent countless hours playing and talking with street children from Brazil to Thailand, as well as meeting with tens of thousands of students, parents, and educators in schools around the world. We have learned important lessons from everyone, from human rights workers in war zones to moms and dads in suburbia, executives in marble-floored offices, and people without any place to call home. With each day that has passed and each new adventure, we've faced a mosaic of human experience and discovered the most surprising thing: amid the extremes of humanity's wealth and poverty, power, and exploitation, happiness is attainable for all. And the most crucial piece of the puzzle is this: true fulfillment starts with finding the courage to reach out.

The main challenge, we believe, is that many of us don't yet know where to start.

In North America, we have frequently been invited to speak at motivational seminars and conferences, where we have met people from all walks of life who are experiencing a sense of dissatisfaction. Many have difficulty explaining exactly what it is that they are looking for, but instinctively they know that something vital is missing.

We believe that the Me to We philosophy can provide both a starting point for change and an antidote for what ails us. We want you to be a part of it, because in our view, this is just the beginning.

When we first set out to write this book, we asked ourselves four key questions:

1. Why are so many people dissatisfied and seeking a different approach to life?

2. What lessons have we learned about the shift from Me to We?

3. How do people stand to benefit from adopting this way of life?

4. How can people start living Me to We right now?

We will explore each of these questions in the chapters that follow, which are packed with true stories to inspire, studies and statistics to persuade, and tried-and-true advice for getting started on your own journey from Me to We.

As you make your way through this book, you will find that doing so involves more than just reading. At the end of each chapter, we have included three special sections filled with ideas and activities designed to help you learn about the power of the Me to We philosophy firsthand. Start Now! sections contain personal questions to get you thinking about the potential for Me to We in your own life, while Take Another Look! sections offer information on important social issues that challenge each of us to move from Me to We. Finally, Living Me to We! sections provide options for action to help you begin living this philosophy. Our suggestions are intended both to spark your imagination and to allow you to make a positive difference not only in our own life, family, and community, but around the world. In each Living Me to We section, one of the featured options allows you to take action on Millennium Development Goals, targets that the international community has agreed to achieve by 2015 (see Appendices). With a focus on eight specific goals and four important themes -- poverty, health, education, and sustainable development -- the Millennium Development Goals offer us all an important opportunity to reach out and live Me to We on a global scale.

In each chapter, we also include a personal story from someone whose life embodies this philosophy. Friends and colleagues have all contributed their own thoughts and experiences, and it is our honor to include original contributions from some of our greatest heroes.

We hope that you will treat each chapter as an invitation -- an invitation to discover the power of the Me to We philosophy for yourself and to join a growing community of people from around the world who are embracing this way of life.

After you've discovered and absorbed the ideas presented in this book, your life may not end up as you had envisioned. You may not acquire a house on a beach in the Caymans, but you may find your toes firmly grounded in the sand. You may not see an enormous change in your social life, but in your life you may very well see enormous social change. You may not find the person of your dreams, but you will help people young and old go beyond theirs. You may not retire with a gold watch, but you will think of the rest of your life as the golden years, no matter what your age.

We have written this book because we have seen what is possible: one small step of kindness contributes to one large step for humankind.

Let us begin.

Craig and Marc

Copyright © 2004 by Craig Kielburger and Marc Kielburger

Copyright © 2006 by Kiel Projects

1

Craig's Story:

"I'm Only One Boy!"

Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked.

--VIKTOR E. FRANKL

Some people's lives are transformed gradually. Others are changed in an instant.

My own moment of truth happened over a bowl of cereal one morning when I was twelve years old. Sitting at our kitchen table munching away, I was about to dive into the daily newspaper in search of my favorite comics --Doonesbury, Calvin and Hobbes, Wizard of Id. The cartoons were my morning ritual. But on this particular day, April 19, 1995, I didn't get past the front page. There was one headline that was impossible to miss:BATTLED CHILD LABOUR, BOY 12 MURDERED.

I read on.

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan (AP) -- When Iqbal Masih was 4 years old, his parents sold him into slavery for less than $16. For the next six years, he remained shackled to a carpet-weaving loom most of the time, tying tiny knots hour after hour. By the age of 12, he was free and traveling the world in his crusade against the horrors of child labor. On Sunday, Iqbal was shot dead while he and two friends were riding their bikes in their village of Muridke, 35 kilometres outside the eastern city of Lahore. Some believe his murder was carried out by angry members of the carpet industry who had made repeated threats to silence the young activist.

(Used with permisssion of The Associated Press, copyright © 1995. All rights reserved.)

After reading this article, I was full of questions. What kind of parent sells a four-year-old child into slavery? Who would chain a child to a carpet loom? I didn't have any ready answers. What I really wanted was to talk to Marc, my older brother by six years, but he was away at college. I knew that even if Marc couldn't answer my questions, he would at least know where to start looking. But that day I was on my own.

After school, I headed to the public library and started to dig through newspapers and magazines. I read about children younger than me who spent endless hours in dimly lit rooms making carpets. I found stories about kids who slaved in underground pits to bring coal to the surface. Other reports told of underage workers killed or maimed by explosions in fireworks factories. My head was swimming. I was just a kid from the suburbs, and like most middle-class kids, my friends and I spent our time shooting hoops and playing video games. This was beyond me.

I left the library bewildered and angry at the world for allowing such things to happen to children. I simply could not understand why nothing was being done to stop the cruelty. How could I help?

I asked myself what Marc would do.

As brothers, we've never been rivals. We are too far apart in age to feel any sibling jealousy. And, as corny as it sounds, we've always been there for each other. When I was younger, I watched in awe as Marc seemed to excel effortlessly in everything -- school, public speaking, rugby, and tennis. But what set Marc apart was his belief that he could make a difference.

When Marc was thirteen, he turned a passion for environmental issues into a one-boy campaign. For an eighth-grade science project, he tested the harmful effects of brand-name household cleaners on the water system. Next he used lemons, vinegar, and baking soda to create environmentally friendly alternatives that did the job just as well, if not better.

Marc seemed to be unstoppable. He gave speeches, founded an environmental club, created petitions, and collected thousands of signatures. As a result, he became the youngest person in our province to receive the Ontario Citizenship Award.

A younger brother could have no better role model. I knew that young people could have the power to make a difference when it comes to issues they care about. Why not me?

Riding the bus to school, I would uncrumple the newspaper article and look at Iqbal's picture -- he was wearing a bright red vest, his hand in the air. One day, I asked my teacher if I could speak to the class. Although I was generally outgoing, public speaking was definitely not my favorite activity. I can still remember how nervous I felt standing up at the front of my classroom and how quiet everyone became as I shared what I knew about Iqbal and the plight of other child laborers. I passed out copies of the newspaper article and shared the alarming statistics I had found. I wasn't sure what would happen when I asked for volunteers to help me fight for children's rights.

Eleven hands shot up, and Free The Children was born.

As I jotted down the names of volunteers, I still didn't know the next step. But as we started to dig up information, things became a lot clearer.

We began researching the issue, and soon after we were out giving speeches. We began writing petitions and held a community garage sale fund-raiser. Before long, Free The Children chapters were popping up in other schools. In a few short months, my family's home literally become a campaign headquarters. Phones rang with news of protest marches led by children. Fax machines churned out shocking statistics on child labor in Brazil, India, Nigeria. The mail brought envelopes from human rights organizations all over the world offering photographs of children released from bonded labor.

Then we learned that Kailash Satyarthi, a leader in the fight against child bonded labor, had been detained. We wrote to the prime minister of India and demanded he be set free. We collected three thousand signatures on a petition and mailed it to New Delhi in a carefully wrapped shoe box. A year later, a freed Kailash came to North America to speak. He called our shoe box "one of the most powerful actions taken on my behalf."

We were making a difference.

Then in September 1995, just as eighth grade was about to begin for me, my mother took me aside. As Free The Children continued to grow, our house had been overrun by youth volunteers, kids were sleeping on couches and floors, and the phone rang at all hours. "This can't go on," she told me. "We have to live as a family. We have to get back to having a normal life."

But how could I give up when I was only getting started?

My parents had instilled in me the belief that goals come with challenges. "Go for it!" they always told me. "The only failure in life is not trying." That's what I thought I was doing, but I guess even they were not prepared for what Marc and I would do with the lessons they had taught us.

I asked for time to think.

As I sat in my bedroom trying to figure out if I should give up or keep going, I thought about how happy I was. Working with a team toward a common goal, I felt a sense of accomplishment and joy. I was happier than I'd ever been in my life. Free The Children was also filling a gap in many kids' lives. At an age when we were constantly being told by adults what to do, this was something we took on voluntarily. I knew in my heart I could not turn back. Too much would be lost. I was no longer the person I had been five months earlier. Besides, there was so much left to do. When I emerged from my room, I told my parents I was sorry, but I could not give up. "You always tell us that we have to fight for what we believe in. Well, I believe in this."

To my surprise, they understood. I think they were even proud. Later, I would learn that the roots of their understanding stretched back generations to the teachings oftheirparents.

When he was just nineteen, our father's father arrived in Canada from Germany during the Great Depression. He earned "suicide pay," fighting boxers in Toronto. It was dangerous work, but every bruised rib or black eye was in his mind a small price to pay for achieving a not-so-humble Depression-era dream. When he had saved enough money, he opened a small grocery store with our grandmother. They worked there day and night, closing only one day in twenty-three years to visit Niagara Falls.

That was how our father grew up: working in the store after school and on weekends. His dream, however, was different. He wanted an education. But he thought there was no chance for college. Then, in his last year of high school, his parents announced that they had saved enough over the years to make his dream possible. He was overjoyed.

Our mother, the second youngest of four children, was born in Windsor, Ontario, just across the border from Detroit, Michigan. She was only nine when her father passed away. At ten she was working weekends in a neighborhood store. There were lots of struggles. One summer her family's only shelter was a tent. Life was hard, but my grandmother, with only an eighth-grade education, taught herself how to type and then worked her way up from cleaning other people's homes to an office job at the Chrysler Corporation (she eventually headed her department). Through her stoic example, she instilled in her children the belief that they could achieve anything they wanted in life.

I was unaware of this history and I was also ignorant of my parents' commitment to supporting social issues. Although they were not activists, both were dedicated teachers who believed in teaching both inside and outside of the classroom. Whenever they had the opportunity, they tried to help us learn about the world and what we could do to make it a better place. These lessons didn't involve marches or protests, they were simpler than that. When we asked a question about the environment, it would lead to an afternoon picking up garbage in the park. A comment about the Humane Society would lead to a challenge to reserve part of our allowance to help the abandoned animals we saw on TV.

Our family history of helping combined to sway my parents. They knew about fighting for ideals and dreams. Our house remained a zoo and Free The Children continued to grow.

Yet if they had known what was coming next, they might have had second thoughts.

Up to that point I had frequently talked with Alam Rahman, a twenty-four-year-old human rights activist and University of Toronto student. He became a mentor to me. I confided in him that I felt some of my statements on child labor lacked authority because I hadn't seen it with my own eyes. We talked frequently about whether I should make a trip to Asia to see for myself. I never really thought it would happen -- I had been begging my parents for months without results.

Then one day, Alam told me that he would be going to South Asia to visit some relatives. Would I like to come? My poor parents never knew what hit them. I pestered them for weeks. Fortunately, they thought very highly of Alam and eventually my mother said, "Convince me that you will be safe."

If I could somehow prove to her that I would be fine, that the trip would be well organized, that the mountain of details could be taken care of, then I could go. I began faxing organizations throughout South Asia advising them that I would be coming, applied for travel visas, and raised money through household chores and the generosity of relatives. Then, with my parents' blessing, I marked the date of my departure on my calendar.

The plan was a seven-week trip to meet children who worked in the most inhumane conditions imaginable. We met children working in metal factories, pouring metal without any protective gear. We met children as young as five years old in the brick kilns, working to pay off debts taken out by their parents or grandparents and passed from generation to generation. We met a ten-year-old boy who worked in a fireworks factory, badly burned all over his body from an explosion that had killed fourteen other kids. In another encounter, we met an eight-year-old girl working in a recycling factory, taking apart used syringes and needles with her bare hands.

My first stop was Dhaka, Bangladesh, where we were taken to one of the city's largest slums, an entire valley filled with corrugated tin, woven reed, and cardboard huts. The people who lived there owned next to nothing. Their clothing was in rags. Human and animal waste filled the gutters. There was little food. When I saw the utter poverty, I wanted to stay there for the entire seven-week trip and volunteer, so I asked a human rights worker in the slum how I could help. He told me, "Continue your journey. Learn as much as you can. And then go back home and tell others what you have seen and ask them if they think it is fair that places like this exist in the world. Because it's the lack of action, the refusal from people at home to help, that allows this to continue."

Later, in Delhi, India, witnessing and learning about the lives of child laborers, I learned that the Canadian prime minister was also there, with eight provincial premiers and 250 business leaders to drum up trade deals. He was not raising the issue of child labor and that angered me. Free The Children's young members had repeatedly asked the prime minister to address this issue, but to no avail. We had written letters and requested a meeting, but the only response we had received was a letter informing us that the prime minister was a very busy person and would not be able to meet with our group. Now, after everything I had witnessed, I was convinced that if he knew of just one of the heart-wrenching stories, he would surely help. I gathered my courage and decided that we needed to do whatever we could to make sure these children's stories were heard. In the end, we decided to hold a press conference.

At the time I had just turned thirteen years old. In my view, the issue at stake in my struggle was one of right and wrong. I was outraged that the prime minister was signing billion-dollar trade deals without even mentioning the children who were making many of the products involved.

One of the most difficult lessons I was learning in Asia was that the fate of the children I met was shaped by the actions of people in wealthy countries like my own, especially people's tendency to consume inexpensive products without wondering how they had ended up on the shelf. I was convinced that once people were confronted with evidence of the suffering caused by child labor, they could not help but want to put a stop to it once and for all.

On the day of the press conference, all of Canada's large television and newspaper outlets were there. I tried to be the most presentable possible, despite having messy hair and wearing a dirty blue T-shirt. I spoke briefly about the horrors of child labor witnessed during my trip and then introduced Nagashir, a new friend, who told his story quietly through a translator.

I had met Nagashir a short time before at Mukti Ashram, a rehabilitation center for freed child slaves. All the children at the center had been forced into bonded labor and abused by their former masters. All had heartbreaking stories to tell, but Nagashir's was particularly horrific. Speaking with him through a translator, I soon realized he had been robbed of his childhood, his humanity violated. He couldn't tell me how old he was when he was sold into bondage; he didn't know. He simply put his hand out to show how small he was at the time. Now, at about fourteen years old, he was a shell. He could barely speak and seemed numb to all around him.

Years ago, a man had come to his desperately poor village with promises of an education and a good job. Like many other children, Nagashir and his younger brother were sent with him and ended up in a factory, working at a loom, tying thousands of tiny knots to make carpets -- for twelve hours a day. In exchange for his labor, Nagashir was given a small bowl of rice and watery lentils at the end of each day. When out of hunger and exhaustion he fell behind in his work, he was whipped and beaten.

It was only the hope of protecting his younger brother that gave Nagashir strength. This same feeling drew the other children together as well, and they relied on each other as a family. When the younger children cried out of homesickness, the older ones would comfort and calm them. When one child was sick, his friends would finish the work on his loom so that he wouldn't be beaten.

Sadly, I learned this wasn't always enough to protect the children. Nagashir showed us the scars that covered his body. His hands were mangled with cuts from the carpet knife. His master, unwilling to lose any productive time, would fill the cuts with gunpowder paste and light them to cauterize the wounds, then send him back to work. Most shocking were the scars on his legs and arms, and against his throat, where he had been branded with hot irons. This had been Nagashir's punishment for helping his younger brother escape from the factory. The lesson was seared into his skin and his soul. Traumatized, he lost his ability to speak; for years he didn't utter a word.

Nagashir was freed from the carpet factory in a midnight raid and brought to the rehabilitation center. At Mukti Ashram, the staff worked with him slowly to help him heal physically and emotionally. Weeks after having arrived at the center, he was found sitting in the garden, singing this song quietly to himself -- his first words in years.

If you want to live, live with a smile,

Live with love, don't cry

Don't shed your tears.

There are storms, there are disasters;

In life there are ups and downs.

But don't shed your tears.

Smile -- pain is part of life,

But finally you get joy.

If you want to live, live with new hopes,

Live with new aspirations.

Live with love.

Live with a smile.

Later, Nagashir was reunited with his family, including his brother. Nagashir and his brother were never again forced to work, and his brother started to attend primary school.

As Nagashir told his story at the press conference, he held out his arms and legs for the cameras, to show his branding scars. The flashes of the camera bulbs were blinding, and we squinted into the large crowd of reporters. It was a frightening yet thrilling experience. But we were united, and with a small group of other children I signed a joint declaration calling on our countries' prime ministers and business leaders to remember the children as they signed their trade deals. It was all we could do.

I left India for Pakistan with no idea that the press conference was carried on networks throughout the world, including CNN. Within no time, the prime minister's handlers were looking for me. He wanted to meet. I was scared, but I also knew it was the best opportunity I'd had to date to voice my concerns.

The meeting went well and ended with the prime minister agreeing to bring up the issue of child labor with the heads of South Asian governments. It was exhilarating and strange. I was only a kid, but people were listening to me. I remember the feeling when I first realized I could actually make a change in the world. It floored me. I felt as if the laws of gravity had been broken. It left my skin tingling with excitement. It still does.

It also had the personal effect of striking down for me one of the most disturbing statements that children often hear: "Kids are to be seen and not heard."

I returned home transformed by the kids I met. But at that point even I didn't know the extent to which my trip would subsequently shape the direction of my life. Almost as soon as I got back to Canada, life in our Thornhill house changed forever. Free The Children had initially started as a group of twelve twelve-year-olds, but now it was gaining an unstoppable momentum.

Of course, we still had a lot to learn. We had to figure out how to create an international movement and still attend high school; help educate child laborers, not just free them; and convince others to join us in our mission, not just be bystanders.

At the time, I didn't think to stop and define my own personal transformation, but years later, as Marc and I reflected on the lessons we took from journeys both at home and abroad, I came to think of it as a shift from "Me" to "We."

Having reached my own turning point almost by chance on an ordinary Wednesday, I'm now passionate about doing all I can to help others arrive at their own crossroads. I believe that every journey from Me to We is as unique as each one of us, filled with twists and turns that lead in directions we might never have expected. I know that as more and more people choose to embark upon this journey, our actions in turn encourage others to find their own routes. When I think about the future, I imagine all of our paths converging, forging a new direction for our society. As I look around today, I can see that this process has already begun.

• • •

FREE THE CHILDREN

www.freethechildren.com

Children Helping Children Through Education

Founded in 1995, Free The Children is the world's largest network of children helping children through education. Through the organization's youth-driven approach, more than one million young people have been involved in innovative programs in more than forty-five countries. Free The Children is committed to creating a generation of active global citizens both at home and overseas, and to connecting young people around the world. In 2006, Craig Kielburger was awarded the World Children's Prize, widely known as the Children's Nobel Prize. Free The Children has three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize and partnerships with the United Nations and Oprah's Angel Network.

• • •

START NOW!

Before you begin this section, find a notebook that can serve as your personal Me to We journal. As you explore the Start Now! activities at the end of each chapter, this journal will be a place to record your thoughts, feelings, and ideas as you begin to make the shift from Me to We a reality in your life and the lives of others.

- What do I feel most thankful for? What makes my heart overflow with gratitude? The words of a loved one? A leisurely stroll through the park?

- What kinds of things make me angry? A war being fought somewhere across the world? Negative attitudes in my community?

- What are the values I hold most dear? What five values guide me as I move through life?

• • •

LIVING ME TO WE

• • •

My Story

Kim Phuc

I still can't look at the picture, not even today. It hurts too much.

That image of myself as a little girl in Vietnam, running with my arms hanging wide, naked, my skin on fire, my mouth open in terror and crying for help, the smoke all around me -- it still is too powerful. I feel so horrible inside, like it's happening all over again. I can smell the burning, I can feel the heat, and deep in my soul, it hurts!

So I don't look. I keep the picture filed away, hidden from view.

But I don't feel hatred for that picture anymore. Instead, I feel grateful. To me, that picture is a gift.

It took a very, very long time for me to feel that way.

For many years, I was just the Girl in the Picture -- and I hated it.

I had been photographed when I was nine years old and my village was hit by napalm. We were running on the highway, away from the explosions. The sky was red, as if heaven were on fire. I could not keep up with my brothers; they ran too fast. As I ran, I turned to see an airplane flying low to the ground. I had never seen one so close before. I watched it drop four bombs into the swirling smoke. I kept running.

Suddenly, a force struck me from behind. I fell forward onto the ground. I did not know what I was doing when I pulled at the neck of my shirt. I just felt so hot. My burning clothes fell away from me. I looked at my left arm. It was covered with flames and brownish-black goo. I tried to wipe it off and yelled in pain as my hand began to burn too.

I knew I should catch up with my brothers, but I felt so tired and so thirsty, like I was burning from the inside. "Oh, Ma," I kept crying."Nong qua! Nong qua!"Too hot! Too hot!

That's when the journalist took my picture.

I hardly remember what happened next. The journalists poured their canteens of water over my skin; it was falling off in pink and black chunks. The photographer got a poncho to cover me, then helped me into a van and drove me to the hospital in Saigon. The van swerved around refugees, and with every bump I screamed in agony. The napalm had incinerated my ponytail and left my neck, my back, and my left arm a raw, mushy, oozing mess. It had killed my two cousins. I wished it had killed me too.

It wasn't until much later that I learned that the picture, taken by AP photographer Nick Ut, had been printed on the front pages of newspapers around the world and won him the Pulitzer Prize. It made Nick famous. It made me famous too, though I wished with all my heart it had not.

For the next fourteen months I remained in an American hospital in Saigon, enduring many surgeries and painful procedures paid for by a private foundation. I had to relearn how to stand, walk, and feed and dress myself. Finally, recovered, I was sent back to my village to try to rebuild my life.

But my life would never be the same.

I could not take the hot sun on my unstable new skin or the blowing dust in my damaged lungs. I suffered bad headaches and sudden, intense pain. My family was forced to live in a hot, airless house in the city as war raged around us. We had little money, not even for the ice I depended on for pain relief.

As the years went by, I remember as a teenager feeling so very ugly! I would look in the mirror at the scars that covered my body and ask, "Why me?" I was able to hide my disfigurement by growing my hair long, wearing long sleeves, and resting my left arm on my hip so you couldn't tell it was shorter.

It was my shameful secret. Once, when I was seventeen, sitting at my desk waiting for the teacher to arrive, I heard some girls talking about a boy who had scars on his hands. "He is so handsome," one girl said. "Ooooh! Yuck!" the others chimed in. "Have you seen his scars? So ugly!"

The only thing that kept me going was my dream of becoming a doctor. I'd been so impressed with how the doctors had helped me; I wanted to help people too. I studied hard and was accepted into medical school. I was thrilled -- but it was short-lived. A few months later, foreign journalists found me. They wanted to interview me ten years after the war.

At first, I was flattered -- me? Famous? But then the Vietnamese communist government took over, demanding that I act as their anticapitalist poster girl, their symbol of the war. They told me what to say and do, watching my every move. They made me abandon medical school and be available to pose for the cameras. Outside, I was smiling; inside, I felt so sad, like I was a victim all over again. I could have no friends; it was too dangerous. They warned my parents that if something happened to me, they would go to prison.

In between media interviews, I went to the library, reading every book I could find on religion. I'd hoped that within those pages I would find some answers, some meaning for my life. There, I found my answer. God, I decided, had saved me for a purpose. Through my new faith, I would find that purpose.

The Vietnamese government finally relented and allowed me to continue my education, this time in Cuba. It was there that I met my husband -- and decided that I would finally escape the clutches of the communist government.

I told no one, just bided my time. And one day, I saw my chance.

It was 1992. My husband and I were returning from our honeymoon in Moscow, and the plane needed to refuel in Canada. I looked out the plane window at the wide open spaces of Gander, Newfoundland. We knew nothing of this country except that it was cold -- and free. That was enough for me. I had never felt so scared in my life -- or so strong. With pounding hearts, we left our bags on the plane and never turned back.

I came here to get away from Vietnam, from the war, and from my life as the Girl in the Picture. I wanted to make my life quiet. It did not work out that way, but that's okay. I have found something else -- something better. I have found my purpose. I travel and speak out to tell people that war is bad, that tolerance and forgiveness are good, that our real enemy is anger and bitterness.

And I have found that people listen. I believe that's because I speak from my heart. They see me as an innocent little girl who suffered so much, who is supposed to be angry, who is supposed to be dead.

Although I did not become a doctor, I did find another way to heal. In 1997, I established the Kim Foundation, a nonprofit group that provides funds for medical assistance to children who are victims of war and terrorism. In 1997, I was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador for Peace for UNESCO.

I could have stayed frozen in time, forever the Girl in the Picture, forever the victim. But I no longer run away, and I am no longer a victim. It was the photograph that saved my life, but it was my reaching out to others that finally convinced me it was a life worth saving.

Copyright © 2004 by Craig Kielburger and Marc Kielburger

Copyright © 2006 by Kiel Projects

Excerpted from Me to We: Finding Meaning in a Material World by Craig Kielburger, Marc Kielburger

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.