Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

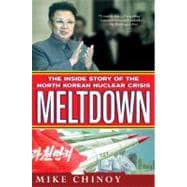

Mike Chinoy is the Edgerton Senior Fellow on Asia at the Pacific Council on International Policy in Los Angeles. Until 2006, he was a foreign correspondent for CNN, largely in Asia, and made numerous visits to North Korea over the course of nearly two decades.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.