Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

My father dead, I come into the room where he lies and I say aloud, immediately concerned that he might still be able to hear me, What a war we had! To my father's body I say it, still propped up on its pillows, before the men from the funeral home arrive to put him into their horrid zippered green bag to take him away, before his night table is cleared of the empty bottles of pills he wolfed down when he'd finally been allowed to end the indignity of his suffering, and had found the means to do it. Before my mother comes in to lie down beside him.

When my mother dies, I'll say to her, as unexpectedly, knowing as little that I'm going to, "I love you." But to my father, again now, my voice, as though of its own accord, blurts, What a war! And I wonder again why I'd say that. It's been years since my father and I raged at each other the way we once did, violently, rancorously, seeming to loathe, despise, detest one another. Years since we'd learned, perhaps from each other, perhaps each in our struggles with ourselves, that conflict didn't have to be as it had been for so long the routine state of affairs between us.

And yet it was "war" that came out of me now, spontaneously, mindlessly, with such velocity I couldn't have stopped it no matter what, but, still, I don't understand why it's this I'd want to say to my father at the outset of his death. As though memory were as wayward and fractious as dream, as indifferent to emotional reasoning, as resistant to bringing forth meanings or truths, verifications that might accord with any reasonable system of values. As though memory had its own procedures of belief and purpose that exist outside of and beyond our vision of our lives.

With my mother, as I remember again now speaking to her in her death, my memory, capricious as ever, brings her to me on the shore of a lake, in a bathing suit. I'm very young--I don't even have a brother or sister yet. My mother is sitting beside me speaking to my father. Bathing suits are made of wool then, even mine, and I'm acutely aware of how rough the fabric must be to my mother's sensitive skin; its abrasiveness is a violation, a desecration: I try to stroke the skin under the straps on her back. My mother smiles at me. My father smiles, too. In the water later, in the shallows, I teach myself to walk on my hands with my body afloat behind me. "Look, I'm swimming!" I cry out in pride to my mother, who, in my memory, breaking off what she was saying then to my father, smiles at me again.

And yet that other spurt of speech from the past, to my father lying before me, as though we'd never effected our unspoken reconciliation, as though we'd never embraced, never, after our decades of combat, held one another, our cheeks touching, our chests for a moment pressed together--to my father come words that seem to contain an eruption of still painful feelings, though I know those feelings have been transformed, transfigured; peace for rage, affection for frustration, devotion and compassion for misunderstanding.

The first time my father and I kissed each other as adults, the first time we managed to move across and through our old enmities, across and through our thousand reservations, our thousand hesitations; the first time we stood that way together, arms around each other, we seemed to me to be uncannily high from the earth: it was as though I were a child again, suddenly stretched to my father's height as I held him, gazing dizzily down in disbelief at the world far beneath us. My mother was there, watching, saying nothing, taken surely at least at that moment with relief for us all, yet too caught in her own timidities and her own travails to dare speak it aloud.

* * *

When my father died, it was difficult to comprehend what my mother felt. She threw herself down on the bed next to my father, and lay there quietly for a long time. She said his name several times; she seemed to want to cry, but didn't.

The week before, when she'd first realized he really was going to die, and soon, she'd said, "Now I'll have to go live with all the other widows." She was saying that after he was gone she'd move to a swank apartment house in a nearby town where many of her friends lived. She meant what she said to sound sorrowful, and certainly something like sorrow did bend her voice, but anyone who knew her well would know too that she was excited by the prospect of buying and decorating a new place to live in, of having so much to do, so much to think about.

She had almost cried when my father first started to become aphasic, when his speech deteriorated so that his words were inappropriate or wildly wrong. She must have been frightened that someone who'd lived so much by his gift for language could sound foolish, or mad. Her eyes reddened when she spoke of those first dreadful weeks when the aphasia was manifesting itself, but still, she didn't quite cry. Several years later, in another context, she happened to mention to me how, when my father had their last dog put away, a clumsy, affectionate hound who'd become hopelessly ill, she'd surprised herself, because she'd sobbed like a baby; she couldn't understand why, she said, the dog had been my father's more than hers.

Does my mother not crying when my father died say something about her character, or their marriage, or the fact that my father had long periods over the last decades of his life when he wasn't a very nice man, and that perhaps she'd never come to terms with it?

That's what she'd said to him once, You used to be such a nice man . It's what I hear her saying again, perhaps near tears, her voice breaking perhaps in anger or sadness or most likely in surprise at her audacity in speaking aloud what sounded so much like a repudiation. No one will ever know now whether she'd cried, or spoken in a torn or angry or infinitely regretful tone when she said it; she was alone with my father, they're both gone now, and, though she reported to me the words she said to my father, it still seems unlikely that she would have done so, no matter how she said them: it wasn't in her character to share very much that went on between my father and her in their very opaque relationship.

Those were the years of my father's most maddening insensitivity and harshness, when he dealt with all of us, even my mother, as though we were his employees, or worse. He tormented all of us, sometimes by his criticism, by the way he had of letting you know you weren't meeting his expectations, sometimes by his inscrutability and unpredictability--you had no idea from one day to the next how he'd respond to you--and sometimes by his indifference, an indifference which by then had begun to invade his entire character, although he himself wasn't yet suffering from it as he would later. They're the long years, which if I'm not careful can entirely determine my memory of my relation to him, even now, even long after we'd made peace and long after I'd understand at his deathbed how complex that peace was. My mother's remark about his no longer being a nice man ostensibly had to do with how badly my father was dealing with my brother, who'd recently gone to work in one of my father's businesses, but the state of relations between my father and my sister and me and his ever increasing distance from my mother would also have to have been a part of her plaint.

I can imagine my father and mother lying there as my mother speaks. Their bed was very wide, and had been made especially long, because my father was so tall. The fact that it was one bed rather than two implied a union between them, but in those last years, glancing in at them at night when I was visiting and came in late, I never saw them--they always left their bedroom door open--in any sort of contact, bodies wound together or hands touching. They slept back to back; when she spoke those words, my mother might have been facing my father, but I imagine him already turned away from her.

He had to have registered her words, though. If there was a break in her voice, he would have had to be aware of it. Would her distress have caused him to search himself to try to find some justice in what she'd said, would it have made him entertain the least possibility that she might be right, and that he might have to do something about it? Such a grievous accusation to hear from one's own wife. His arms complicatedly folded under his head as they always were when he slept, would he have felt in himself some sadness, some loss, some possible need for repentance or change?

My father had long before sworn that he'd never again say he was sorry, for anything, to anyone. No one ever knew what had brought him to such a resolve, nor did we ever know either what had made him tell my mother about his promise to himself, but she was aware of it, so she would have known not to expect anything like an excuse, or a vow to do better, or any sort of evasion or deflection which could have been interpreted as an apology.

Might he have taken what she said as simply an attack, something in the struggle between them, which might have made her words easier to deflect? My father didn't suffer slights easily; if he thought my mother meant merely to assail him, he'd have slashed back. Would he have allowed her remark to hurt him? Was there still enough feeling in him in those days, enough vital, active, living emotion connecting him to his wife, to any of us, so that what she said would have mattered to him in any deep way? If it had, what then? If he had absorbed her words, and taken into himself what she had said, then he probably would at first have irritably demanded of the void of the night whether she really wanted him to recast the character he'd spent his whole life hammering into existence; "spent" in the sense of paid, paid out, soul and body, conscience and emotion, until he was often in a state of physical and spiritual exhaustion. And what would the night have dared reply?

* * *

This was the room in which my father would die. For me now, anything that ever happened in that room can seem to have already present in it those two events: my mother saying what she did to my father, and his death, the death he would will for himself in that same bed; his death rests off to one side, silent, patient, so that my father as my mother speaks to him seems to be lying alongside himself, and the likelihood of his replying seems as slight as if my mother were speaking to that future ghost.

I don't really know if her words hurt him, and yet they hurt me, even now. Whenever they come to mind, they arrive with a shock, of shame, of remorse, as though I had to feel for my father what he was incapable of feeling, or of knowing he was feeling. I can still sense, too, as though I were there with them, how the tiny corner of the night their bedroom contained goes utterly still with my mother's waiting for my father to reply or not reply, and with his deciding whether he will or won't. Or not deciding: it would have to have been something so deep within him that replied that there couldn't have been any actual decision on his part; anything he said would have had to have come out of him spontaneously, without his thinking it first, and he would immediately have had to make clear to both my mother and himself that there was no surrender or submission, even a surrender to whatever in himself had caused him to speak, to be inferred from his response. Submission was an act, a phenomenon, it would have been unthinkable for him to let anyone, even himself, inflict upon him. An upsurging, then, perhaps of a connection long forgotten, long ago put aside so it wouldn't interfere with his crucial interchanges with himself, with the reality he'd shaped to contain those interchanges.

Meanwhile, he still hasn't spoken. I can tell even from here how much he would have wanted to be asleep by then; how much he wishes to be left alone. Can he ever be alone again with her there waiting beside him, having said that? Could he bring himself to ask her to explain, or elaborate on what she'd said? "You used to be such a nice man." Certainly it would have needed explication. Certainly he must have been abashed at having his life so compressed, condensed into what was, after all, considering how circumspect my mother normally was with him, a devastating accusation. Yet I can't find in my memory any evidence to show that what she said changed in any way how he acted during those years. I can't imagine either any reply he might have made to her. There's only the silence, and, for me, that image of his death waiting beside him, already beginning to absorb him.

* * *

Perhaps my mother didn't cry when my father died because she was exhausted by all the months of not knowing what was happening to him, then by those last weeks of having to accept that the tumors in his body and his brain were conquering him. It was appalling to behold for all of us, although in the days before his going, when he'd come to terms with knowing he was dying and was only upset because he couldn't convince any of us to help him to get it over with as quickly as possible, he became more gentle, more kind and attentive, solicitous and affectionate, especially to her, than he'd been in many years, and perhaps ever. But my mother, though pleased by his change, still hung back from accepting this near-deathbed transformation, as though she didn't quite believe it.

To me they were very important, those last days. I would chat with my father to try to distract him from his single-minded insistence that someone had to get him whatever pills or injections he needed to kill himself, to end the humiliation his disease was inflicting on him. He had fresh, raw scars on his forearms, the hesitation marks of someone who's tried to do away with himself with a blade; he hadn't been able to do that, but was determined to find another way. You couldn't talk to him for five minutes about anything else without his coming back to suicide, and it wasn't until we told him that someone would, indeed, help him that he would pay attention for more than a few minutes to what you were saying.

Before that happened, though, one afternoon when he was telling me again, yet again, that he wanted me to help him end his ordeal, I tried to change the subject by convincing him that these last days, these last hours we were having together were precious, and that we should try, to have as many as we could. As I spoke, tears came to my eyes, my father saw them, his eyes filled, too, and he said, "We were kids together, you and I."

I was very moved; I hadn't seen him in tears for so long. The last time was when I was twenty, when I'd gone away for some months to Europe to try to teach myself to write. I didn't call, wrote few letters, came back on an impulse--I couldn't bear my loneliness anymore--and arrived unannounced. My father wasn't at the house when I got there; my mother of course was glad to see me, but she was in a hurry: she was just leaving to meet my father at a bris, the circumcision service of the son of my father's younger brother, and she took me with her. My father was there when we arrived; he glanced at my mother, then at me, did a sort of double-take, and then the tears came--he had to take off his glasses and use his handkerchief to dry his eyes. Now, this afternoon during the days of his dying, to behold him so taken by a nostalgia for our shared past surprised and gratified me, and I sensed that he wouldn't come to act later as though he regretted his expression of affection, which he still, despite all, occasionally did.

It's true we'd all been young back then, he and my mother and I. My mother and he were both twenty-two when I was born, it was the Depression and they were frighteningly poor--my mother talked even at the end of her life about not having had enough money to buy me an ice cream, and about their slum apartment where she had to stamp her foot when she opened the door so the cockroaches would have time to hide before she turned on the light. There was something about us being poor together--or perhaps for my father it was the novelty of being a husband and father, or it might have been just that he still loved my mother then without qualification--that bound the three of us together in a way the family never quite would be again, except perhaps at parties, when we were a little tipsy and my mother was in her rapture about giving or being part of a celebration, and my father ...

I don't really know what my father felt even at those times when the rest of us could unbend, and we could be pretty certain for a while, as we never were during his bad times, that he wouldn't strike out at one of us. He was more accessible then, and he was as friendly and warm with us as he was with his friends and business associates, but you still never really knew.

Before the reconciliation he made with me, and with my brother and sister, he could be dreadful, he could be, well, a prick. I've known people who could say something to hurt you, but my father could keep at you, minute by minute, with a disconcerting insistence, as though he had every right to do it, and should immediately be, not forgiven, because he didn't ever find anything at all wrong with what he'd done, but comprehended, given credence, even if the pain he inflicted had been meant to burn, and endure.

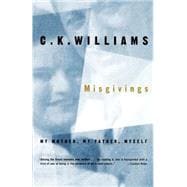

Copyright © 2000 C. K. Williams. All rights reserved.