Chapter One

I skidded on a patch of ice as I rounded the corner onto Lafayette Street, only years of experience saving me as I tottered in the bare twelve inches between a shuttered horse- drawn hansom and a Model- T. The white- gloved matron behind the wheel had clearly come to regard her motor vehicle the way one might a pet cat that always vanished at the full moon, and the sight of my bicycle sliding gracefully past broke her remaining self- control. I can’t imagine what she found so terrifying about me. Unless it was the grin I couldn’t keep from my face as I dared the January ice. Daddy always did say I was too reckless in winter.

The matron shrieked and discovered the purpose of that curious little button in the middle of her steering wheel. Her car swerved— thankfully away from the horses, which were even now whinnying and snorting in agitation. I made it past the hansom and auto moments before one of the horses reared and whacked the Model- T’s gleaming rear fender. I winced. Two more seconds and that would have been my stomach.

Damn Tammany Hall, I fumed. Like it would kill those bastards to do something useful like fixing roads between winning elections? Tonight, of course, the criminally narrow streets were relatively clear. No one respectable wanted to be out after sundown on a new moon. I checked my watch— quarter ’til eight— and pedaled faster. It wouldn’t do for the teacher to be tardy to her own class. Especially not this class. And especially not on a new moon.

That’s when I saw it, of course. Just a huddled shadow on an unspeakably dirty street that hundreds of people had probably passed by today without comment. I sailed past it, too, before something made me dig my heels into the ground and turn around to ride back. It wasn’t as though the back of my neck prickled, or I felt a telltale shiver crawl up my skin. I can’t do anything like that, no matter what my students might whisper about me. But I do have a knack for noticing. It’s a skill my daddy cultivated, since I can’t shoot fish in a barrel and he needed his eldest to be good at something.

I had to kick the spokes to turn the handlebar hard right, then jigger them back out again so I could straighten the wheel. I crashed over the drainage ditch and slid on the worn soles of my boots over the sidewalk. I was deep in the shadow of a monolithic, grimy tenement— the kind that put me in mind of hollow- eyed immigrant children chained to beds by unscrupulous landlords so they won’t escape. They hired vampire guards in those kinds of hellholes. I shuddered and looked, suddenly, back at the street. Deserted. I think the hair on the back of my neck would have risen then, if it weren’t already smothered by the respectable starch of my shirt collar.

I walked closer to the crawlspace— too small to even be an alley— between the tenement and a former munitions ware house. A rat, startled by my approach, scrambled over a gray heap that was barely distinguishable from the other refuse and shot into the gutter by my bicycle. My eyes adjusted to the gloom. I could finally see the faint outline of the innocuous little hump that had so firmly caught my attention. It was covered in a child- sized peacoat that smelled of damp wool. Shaking— because by God there is no way to get used to this, no matter how long I’ve lived in this city— I pulled back the cloth. I saw a boy, with hair much redder than my own ochre- tinged brown. His skin was so pale beneath a shock of freckles that I knew what had happened even before I spotted the telltale punctures on his neck.

I sat back on my heels and clenched my teeth. His neck held seven separate wounds— shallow and rough, like they’d been teasing him. I’d bet that if I pulled down the collared shirt and suit jacket—finely made, but worn— I’d see more along his back and arms. It looked like some sort of hazing ritual, and maybe a bit of revenge. It looked like the Turn Boys, and was just one more reason for me to despise them. The young vampire gang ran roughshod over their chosen kingdom of Little Italy and the greater Lower East Side. This poor kid was rather far down Lafayette for their activities, but I didn’t doubt for a minute who had done this. I’d seen enough of their work to know.

A solitary car sped behind me on the road, sending a spray of icy mud over my bicycle and splashing onto my blue tweed skirt. I glanced at my watch. Ten minutes ’til eight. Damn. I had just enough time to speed down to the police station, report the body and get to class. But I also knew what the police would do when they got him. They didn’t take any chances— especially not with the anonymous immigrant children. Too many kids went missing to waste the precious time hunting in one of the hundreds of lower Manhattan tenements for a distraught mother who probably didn’t speak any English. So they took them to the morgues, turned up the electric lights, and staked them. Sometimes they cut off their heads for good measure, if turning looked likely.

This boy wouldn’t keep his head. He reminded me a bit of my little brother Harry, back in Montana. The same freckles and shock of red hair. He wore one forlorn blue mitten— the other must have fallen off in the struggle.

"Zephyr," I told myself sternly, attempting to speak some sense to my paralyzed brain, "Harry still laughs about putting a beehive in your knickers. It ain’t him."

At which good, rousing inducement to sanity I discovered myself scooping the pathetically light body from the ground and toting it back to my bicycle. I always knew the situation was serious when I resorted to country grammar.

I didn’t know what I was doing. I swear I almost never do— I operate on nothing but horrible instincts and a dash of self- preservation. I draped the boy around my shoulders, wrestled the handlebar straight and started back down the street. I could leave him in the school building. It ought to be safe.

I huffed and pedaled faster, sweating now with the exertion. The boy wasn’t heavy, but I’ve never been that strong and I’d just come back from a crisis across the bridge in Brooklyn. A Russian immigrant with a husband and kids, turned a week ago, had apparently missed the warning about alcohol. Or maybe she’d heard it, and dismissed it along with the rest of the Temperance Union’s hand-wringing hogwash. I might have had little personal experience with Demon Alcohol, but there was no comparison between what it did to my little sister when she found her way into Daddy’s stash, and what it did to Others unfortunate or reckless enough to imbibe. A fit of the giggles and a morning headache was nothing compared to . . . well, that.

The Russian vampire’s skin had turned red, they told me. Not just flushed, like your average speakeasy drunk. Oh no, bloodred. It started to bead on her skin, like sweat. It dribbled from her mouth. Her children were terrified, of course. No one had told them what had happened to their mother— only that she was sick. A week’s legally- acquired blood puddled onto the floor, burning through the wood with its foul- smelling venom. The oldest child and the father ran away. The youngest must have frozen— with shock, fear, disbelief, God-only-knows—because he stayed behind. The father didn’t realize until it was too late. The mother— blood starved, drunk, newly- turned and not a little crazed— turned upon her child and fed. She realized what she had done when she was sated. Too late.

Troy Kavanagh’s pack of Defenders got to her first. He told me the woman begged them to stake her. They obliged, along with the boy. Kids are too dangerous to let turn. Or so Defenders like Troy claim. I know him from way back. Even before New York. He’d met my daddy for some big, legendary Yeti hunt up in north Montana, and when I came down here I worked with his group for a while. I may not be much of a shot, but you can’t be the oldest daughter of the best demon hunter in Montana without learning a few tricks. I pulled my weight, but I had to leave. The Others might not be human, but they’re still people, you know? Troy never seemed to get that.

He called me in during the cleanup to deal with the new widower and his son. Said it called for a "delicate hand." Troy thinks a strong jaw makes up for a lousy personality.

So I’d been on my bicycle all day and my tailbone felt like someone had been smashing it with a mallet and I had a dead boy— the kind you’re never supposed to let turn, if you’re an ignorant Other-phobe like Troy— who could double as a vampire pincushion draped across my neck and damn if I wasn’t getting some odd looks as I huffed my way through the busy Canal Street intersection. Why did things like this always happen to me?

I had to laugh, and saw my breath float away in the glare of the electric lamps. Because I’m certifiable.

Two minutes to eight, I shot past a snarl of traffic on Bowery and stopped at the corner of Rivington and Chrystie. Sweat dripped down my neck and made my shirt cling to my back. My buttocks were still quite wet. My toes seemed to have lost all feeling. I leaned, trembling, over the handlebars and panted. Behind me rose the ragged edifice of Chrystie Elementary, smog- crusted and sporadically heated. Only three of its classrooms are equipped with electric lighting, and even that is about as reliable as a succubus in heat. An immigrant school— with quite a few Others, no less— was not a high priority for our delightful city government.

The boy on my neck started to groan. Not a normal groan— you know, made of air and vocal cords and wholesome biology. A distinctly otherworldly one that should have been impossible for such a small child...

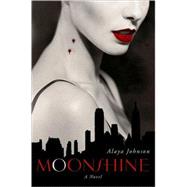

Excerpted from Moonshine: A vampire suffragette Novel by Alaya Johnson.The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

I skidded on a patch of ice as I rounded the corner onto Lafayette Street, only years of experience saving me as I tottered in the bare twelve inches between a shuttered horse- drawn hansom and a Model- T. The white- gloved matron behind the wheel had clearly come to regard her motor vehicle the way one might a pet cat that always vanished at the full moon, and the sight of my bicycle sliding gracefully past broke her remaining self- control. I can’t imagine what she found so terrifying about me. Unless it was the grin I couldn’t keep from my face as I dared the January ice. Daddy always did say I was too reckless in winter.

The matron shrieked and discovered the purpose of that curious little button in the middle of her steering wheel. Her car swerved— thankfully away from the horses, which were even now whinnying and snorting in agitation. I made it past the hansom and auto moments before one of the horses reared and whacked the Model- T’s gleaming rear fender. I winced. Two more seconds and that would have been my stomach.

Damn Tammany Hall, I fumed. Like it would kill those bastards to do something useful like fixing roads between winning elections? Tonight, of course, the criminally narrow streets were relatively clear. No one respectable wanted to be out after sundown on a new moon. I checked my watch— quarter ’til eight— and pedaled faster. It wouldn’t do for the teacher to be tardy to her own class. Especially not this class. And especially not on a new moon.

That’s when I saw it, of course. Just a huddled shadow on an unspeakably dirty street that hundreds of people had probably passed by today without comment. I sailed past it, too, before something made me dig my heels into the ground and turn around to ride back. It wasn’t as though the back of my neck prickled, or I felt a telltale shiver crawl up my skin. I can’t do anything like that, no matter what my students might whisper about me. But I do have a knack for noticing. It’s a skill my daddy cultivated, since I can’t shoot fish in a barrel and he needed his eldest to be good at something.

I had to kick the spokes to turn the handlebar hard right, then jigger them back out again so I could straighten the wheel. I crashed over the drainage ditch and slid on the worn soles of my boots over the sidewalk. I was deep in the shadow of a monolithic, grimy tenement— the kind that put me in mind of hollow- eyed immigrant children chained to beds by unscrupulous landlords so they won’t escape. They hired vampire guards in those kinds of hellholes. I shuddered and looked, suddenly, back at the street. Deserted. I think the hair on the back of my neck would have risen then, if it weren’t already smothered by the respectable starch of my shirt collar.

I walked closer to the crawlspace— too small to even be an alley— between the tenement and a former munitions ware house. A rat, startled by my approach, scrambled over a gray heap that was barely distinguishable from the other refuse and shot into the gutter by my bicycle. My eyes adjusted to the gloom. I could finally see the faint outline of the innocuous little hump that had so firmly caught my attention. It was covered in a child- sized peacoat that smelled of damp wool. Shaking— because by God there is no way to get used to this, no matter how long I’ve lived in this city— I pulled back the cloth. I saw a boy, with hair much redder than my own ochre- tinged brown. His skin was so pale beneath a shock of freckles that I knew what had happened even before I spotted the telltale punctures on his neck.

I sat back on my heels and clenched my teeth. His neck held seven separate wounds— shallow and rough, like they’d been teasing him. I’d bet that if I pulled down the collared shirt and suit jacket—finely made, but worn— I’d see more along his back and arms. It looked like some sort of hazing ritual, and maybe a bit of revenge. It looked like the Turn Boys, and was just one more reason for me to despise them. The young vampire gang ran roughshod over their chosen kingdom of Little Italy and the greater Lower East Side. This poor kid was rather far down Lafayette for their activities, but I didn’t doubt for a minute who had done this. I’d seen enough of their work to know.

A solitary car sped behind me on the road, sending a spray of icy mud over my bicycle and splashing onto my blue tweed skirt. I glanced at my watch. Ten minutes ’til eight. Damn. I had just enough time to speed down to the police station, report the body and get to class. But I also knew what the police would do when they got him. They didn’t take any chances— especially not with the anonymous immigrant children. Too many kids went missing to waste the precious time hunting in one of the hundreds of lower Manhattan tenements for a distraught mother who probably didn’t speak any English. So they took them to the morgues, turned up the electric lights, and staked them. Sometimes they cut off their heads for good measure, if turning looked likely.

This boy wouldn’t keep his head. He reminded me a bit of my little brother Harry, back in Montana. The same freckles and shock of red hair. He wore one forlorn blue mitten— the other must have fallen off in the struggle.

"Zephyr," I told myself sternly, attempting to speak some sense to my paralyzed brain, "Harry still laughs about putting a beehive in your knickers. It ain’t him."

At which good, rousing inducement to sanity I discovered myself scooping the pathetically light body from the ground and toting it back to my bicycle. I always knew the situation was serious when I resorted to country grammar.

I didn’t know what I was doing. I swear I almost never do— I operate on nothing but horrible instincts and a dash of self- preservation. I draped the boy around my shoulders, wrestled the handlebar straight and started back down the street. I could leave him in the school building. It ought to be safe.

I huffed and pedaled faster, sweating now with the exertion. The boy wasn’t heavy, but I’ve never been that strong and I’d just come back from a crisis across the bridge in Brooklyn. A Russian immigrant with a husband and kids, turned a week ago, had apparently missed the warning about alcohol. Or maybe she’d heard it, and dismissed it along with the rest of the Temperance Union’s hand-wringing hogwash. I might have had little personal experience with Demon Alcohol, but there was no comparison between what it did to my little sister when she found her way into Daddy’s stash, and what it did to Others unfortunate or reckless enough to imbibe. A fit of the giggles and a morning headache was nothing compared to . . . well, that.

The Russian vampire’s skin had turned red, they told me. Not just flushed, like your average speakeasy drunk. Oh no, bloodred. It started to bead on her skin, like sweat. It dribbled from her mouth. Her children were terrified, of course. No one had told them what had happened to their mother— only that she was sick. A week’s legally- acquired blood puddled onto the floor, burning through the wood with its foul- smelling venom. The oldest child and the father ran away. The youngest must have frozen— with shock, fear, disbelief, God-only-knows—because he stayed behind. The father didn’t realize until it was too late. The mother— blood starved, drunk, newly- turned and not a little crazed— turned upon her child and fed. She realized what she had done when she was sated. Too late.

Troy Kavanagh’s pack of Defenders got to her first. He told me the woman begged them to stake her. They obliged, along with the boy. Kids are too dangerous to let turn. Or so Defenders like Troy claim. I know him from way back. Even before New York. He’d met my daddy for some big, legendary Yeti hunt up in north Montana, and when I came down here I worked with his group for a while. I may not be much of a shot, but you can’t be the oldest daughter of the best demon hunter in Montana without learning a few tricks. I pulled my weight, but I had to leave. The Others might not be human, but they’re still people, you know? Troy never seemed to get that.

He called me in during the cleanup to deal with the new widower and his son. Said it called for a "delicate hand." Troy thinks a strong jaw makes up for a lousy personality.

So I’d been on my bicycle all day and my tailbone felt like someone had been smashing it with a mallet and I had a dead boy— the kind you’re never supposed to let turn, if you’re an ignorant Other-phobe like Troy— who could double as a vampire pincushion draped across my neck and damn if I wasn’t getting some odd looks as I huffed my way through the busy Canal Street intersection. Why did things like this always happen to me?

I had to laugh, and saw my breath float away in the glare of the electric lamps. Because I’m certifiable.

Two minutes to eight, I shot past a snarl of traffic on Bowery and stopped at the corner of Rivington and Chrystie. Sweat dripped down my neck and made my shirt cling to my back. My buttocks were still quite wet. My toes seemed to have lost all feeling. I leaned, trembling, over the handlebars and panted. Behind me rose the ragged edifice of Chrystie Elementary, smog- crusted and sporadically heated. Only three of its classrooms are equipped with electric lighting, and even that is about as reliable as a succubus in heat. An immigrant school— with quite a few Others, no less— was not a high priority for our delightful city government.

The boy on my neck started to groan. Not a normal groan— you know, made of air and vocal cords and wholesome biology. A distinctly otherworldly one that should have been impossible for such a small child...

Excerpted from Moonshine: A vampire suffragette Novel by Alaya Johnson.