| Acknowledgments | 11 | (2) | |||

| Foreword | 13 | (2) | |||

|

|||||

| Introduction | 15 | (4) | |||

|

19 | (8) | |||

|

27 | (14) | |||

|

41 | (13) | |||

|

54 | (18) | |||

|

72 | (17) | |||

|

89 | (30) | |||

|

119 | (43) | |||

|

162 | (52) | |||

|

214 | (27) | |||

|

241 | (11) | |||

|

252 | (33) | |||

|

285 | (15) | |||

|

300 | (29) | |||

|

329 | (21) | |||

|

350 | (20) | |||

|

370 | (14) | |||

|

384 | (20) | |||

|

404 | (21) | |||

|

425 | (48) | |||

|

473 | (23) | |||

| Epilogue | 496 | (4) | |||

| Appendix I Chronology of Key Dates in Forming the U.S. Constitution | 500 | (1) | |||

| Appendix II Gettysburg Address | 501 | (1) | |||

| Appendix III Universal Declaration of Human Rights | 502 | (5) | |||

| Appendix IV The Earth Charter | 507 | (6) | |||

| Endnotes | 513 | (8) | |||

| Bibliography | 521 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

PUBLIC SERVANT

It was near the end of the first year of the 104th Congress, the first Republican-controlled Congress in nearly four decades. Illinois's senior member, Representative Sidney Yates, had just formally introduced me, and House Speaker Newt Gingrich had officially sworn me in as a member of the U.S. Congress representing the Second Congressional District of Illinois. I stood nervously on the floor in the well of the House and made a brief speech ending the official ceremony. Now members were coming over to shake my hand and welcome me as the newest member of their illustrious club.

About a minute into this very warm, welcoming ritual--it couldn't have been more than the seventh or eighth hand I shook--Representative Bill Lipinski, my neighboring colleague from the Third Congressional District of Illinois and a very important member of the House Transportation Committee, stepped forward, shook my hand, and said, "Young man, I want you to know that I can be very helpful to you during your stay here in Congress, but you're never going to get that new airport you spoke about during your campaign."

I had been a member of Congress for all of two minutes and already somebody was telling me how he could help me--and in the same breath vowing to hurt me. I thought: "Welcome to hardball politics."

All of this occurred on Thursday morning, December 14, 1995. Just two and a half weeks earlier, having taken a leave from my position as national field director of my father's progressive political organization, the Rainbow Coalition, I had been a Democratic candidate in a specially called election. The congressman I was replacing, Mel Reynolds, had resigned about two months earlier over a scandal involving sex with a sixteen-year-old campaign worker, and Illinois Governor Jim Edgar had called the special primary and general elections to be held on November 28 and December 12, respectively. I won the primary--to many, unexpectedly--with 48 percent of the vote in a hotly and closely contested seven-person race. On December 12 I won the special general election rather easily with 76 percent of the vote in a heavily Democratic district.

Both Bill Lipinski and I are Democrats, and though we sometimes represent polar opposites of the political spectrum within the Democratic Party, I have come to hold a great deal of respect for him professionally. After all, he was only protecting the legitimate economic interests of his constituents embodied in Chicago's Midway Airport. In fact, to a certain extent because of his sometimes brutal honesty and candid approach to politics--a throwback to old-time Chicago ethnic and machine politics--I have even come to like him personally. I certainly now consider him a friend, and I think the feeling is mutual. In casual private conversations he often refers to my very good friend Rod Blagojevich as "salt" and to me as "pepper," his humorous way of pointing out our racial differences. But despite our friendship, I've also continued to fight hard for a new airport that would benefit the people of my district, yet not hurt him or his constituents' interests.

Bill Lipinski aside, one of the many lessons I have learned since coming to Congress is that there are members in the Democratic Party with whom I almost always agree on the issues, but don't particularly care for personally. On the other hand, there are Republicans with whom I almost never agree when it comes to ideas, programs, and legislation, but whom I like and enjoy being around personally. For instance, Henry Hyde and I disagree on almost everything politically--the one exception is an economic partnership we formed to build the new airport for the suburbs south of Chicago--but I enjoy his company personally and love to give him his favorite cigars. Dick Armey and I are on completely opposite political wings, but we have gone fishing together and had a terrific time. During a trip to Asia in the middle of the late-1990s financial crisis, I not only learned to appreciate Jim Leach as a learned congressman, but also came to really like him as a person. I often give my friend David Drier his favorite cigars as well, and I was among the first in the cloakroom urging former member Bob Livingston to reconsider his resignation. I've come to realize that such odd couples, and the mixture of personal friendship and professionalism, are part of Capitol Hill politics.

Just two days had elapsed between my victory and my swearing-in. Usually, members are elected during the first part of November in one year and take office nearly two months later at the beginning of the next year. The new members and their chiefs of staff go through freshman orientation at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and are briefed by their party's leaders and others. They assemble a staff and become acquainted with legislation and other issues expected to come immediately before Congress. They also learn the mechanics of the legislative process by studying House rules and procedures, all contained in very thick and imposing books. For new members, just getting to know where the buildings and offices on the Hill are is a major task.

On December 14, 1995, I came into office without any such orientation, and the House was in full swing. Congress was nearing the end of a frenetic first session of the 104th, in which Speaker Gingrich and his new band of Republican conservatives had led an ideologically driven crusade throughout most of the year, the result of an overwhelming takeover of Congress through electoral victories in November 1994. Basking in their majority, they aggressively pushed to get the ten items of their Contract with America enacted into law.

On the morning of my swearing-in, I learned the location of my office--Room 312 in the Cannon House Office Building, just across the street from the Capitol. I didn't yet have the key. I had no staff. Just that day I had received my small plastic voting card--but I didn't know how to use it to vote. The General Services Administration had closed two previous district offices in Illinois. Even though Paul Simon, the senior senator from my state, had been extremely kind and helpful leading up to my swearing-in ceremony, I was now essentially on my own.

After the afternoon whirlwind of photo ops, press interviews, receptions, and congratulations had subsided, reality set in. I was now a full-fledged member of Congress, fully responsible and accountable as a government official to nearly six hundred thousand people in my district, to the Constitution, and to laws of the United States. Moreover, I was a new standard-bearer for the sacrifice, service, expectations, and good name that my family had given me. But I would have to make my own way. Suddenly, the task before me seemed overwhelming. I said to myself, "What in the world have I gotten myself into now?"

That same night about 6 PM, my father; his longtime aide and my co-campaign manager, Frank Watkins; my wife, Sandi; my brother Jonathan; Lorraine Westbrook, a friend and former coworker at the Rainbow Coalition; and I met in my office to brainstorm for candidates for chief of staff. After my father expressed his pride in me and offered words of encouragement, we got down to business. Sandi suggested Licia Green, who had experience working on Capitol Hill and was known and respected by each of us because she had worked with us in my father's presidential campaign of 1988. We decided to approach her.

It turned out that Licia had been offered and was considering a job at the White House, but with prayer and persuasion, she was in my office Monday morning heading up my staff. It was one of the best moves I have ever made.

Lorraine and Myra Outlaw, both former Rainbow staff members, also came aboard to temporarily tide us over.

As Licia began to assemble a staff, I instructed her to retain no holdovers from Representative Reynolds's staff and to create a diverse office, reflecting both genders and the races and religions in my district. Licia, who had worked with the late Representative Mickey Leland (D-TX) and had become chief of staff to his replacement, Craig Washington, began reaching out to friends and colleagues. Lorraine became the scheduler and executive assistant and Myra the receptionist and office manager.

Representative Ike Skelton (D-MO) showed me how to use my voting card. The day after I was sworn in, I cast my first three votes, including one against building more B-2 bombers. But with a sparse staff and little time to acquaint myself with the issues, a big mistake was almost unavoidable. The next week, I voted for a piece of legislation that I should have voted against--the Securities Litigation Reform Act. It was the wrong vote, a vote against the interests of my constituents and consumers.

Being the good newspaperman that he is, Chicago Sun-Times reporter Basil Talbott called Reverend Jackson at the Rainbow to get a comment from him on my voting counter to his position on the issue. About a year earlier, my father had joined in signing a letter to members of Congress written by Ralph Nader's Public Citizen against the legislation. Ralph Nader immediately made the letter public, put my "yes" vote on the Internet, and accompanied it with scathing criticism of my departure from my father's more progressive and more consumer-oriented position. It's not that I haven't taken positions different from my father's--though we usually agree on the substance of most issues--but in this instance I had taken the wrong position and deserved to be criticized. It was a learning experience.

I realized that as a congressman I needed help in clarifying issues and positions and creating continuity in regard to my father and the Rainbow Coalition. I pleaded my case to Reverend Jackson--that's how I refer to him when he's my boss, not just my father--and asked if I could hire one of his key staff members, Hilary Weinstein, as my legislative director. He obliged. Hilary had gained some legislative experience through working on the Rainbow's "DC Statehood" campaign, and she knew the progressive Rainbow position on most issues. She immediately joined my staff. An old law school friend, Rodney Emery, subsequently joined Hilary, and weeks later, Tariq Ahmed, formerly a staff member of Congressman Craig Washington, completed the legislative team.

I also opened two new offices in my district, two-thirds of which is in the suburbs and one-third in Chicago. In terms of population, however, two-thirds of the voters reside in Chicago. Slowly, Licia put the district team in place.

Back on Capitol Hill, I had found the quickest route from my office to the House floor, and I no longer got completely lost when journeying to caucus rooms and other offices. I had also mastered the most fundamental of the House rules and floor procedures. Overall, things were beginning to take shape.

My choice for press secretary, however, had not worked out, and I needed to hire a replacement. Lacking solid advice and training in dealing with the press, I was still hesitant to give public speeches and press interviews. I wanted Frank Watkins, my father's press secretary, speechwriter, and political adviser for nearly twenty-seven years, to join me. Frank and I had worked closely together at the Rainbow. Frank had planned and, along with Alice Tregay, co-managed my congressional campaign. And we had a good personal relationship. Frank had chosen to return to the Rainbow after the campaign but agreed to join me if I could work it out. I knew that this was going to be a really tough one with my father, but I asked him anyway. Let's just say that in time he was gracious enough to allow it to happen with his blessing, and so on March 25, 1996, Frank came on board.

Not long after, I gave my first floor speech--one of the opening "one-minute" speeches that usually start each legislative day. Any member can speak about anything for one minute. Frank and I had prepared a statement attacking Republicans who were cutting federal funds for education. In the middle of my minute, I began to feel a little too comfortable, departed from my text, and launched into a personal attack on the likely Republican presidential nominee, Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, calling him by name as one of the major leaders and culprits in this anti-public-education campaign.

At the time, I had read some of the general House guidelines for floor speeches, but I didn't know enough of the details. Calling a person's name is considered a personal attack on the House floor, especially a member of the Senate who isn't there to defend himself; it's completely out of order and against congressional rules. As I stepped away from the podium, I noticed out of the corner of my eye some initial movement toward the microphone by a couple of Republicans, but I didn't know why. Then they quickly went back to their seats. I suspect it was because they remembered that I was new, and they apparently also noticed that Representative Ike Skelton was calling me over. He immediately sat me down and patiently explained the rule and the protocol. I was grateful to those Republicans for not embarrassing me after my first floor speech and to Ike Skelton for his concern for me and for the decorum of the House.

I knew some of the pitfalls that a young Jesse Jackson, Jr., would experience both inside and outside Congress. I also knew that there would be both positive and negative expectations of me. Many times during the campaign and since, I have been asked by reporters to explain the advantages and disadvantages of being the son of the Reverend Jesse L. Jackson--a two-time presidential candidate, a longtime national and international human rights leader, and a world icon. My stock reply: "I inherited both his friends and his detractors, neither of whom I had earned. Thus, I must work hard and, on my own merit, earn the respect of his friends." But I also hoped that his detractors would at least give me a fair hearing and a fair chance. If they did, maybe, just maybe, they would also gain a greater respect for, appreciation of, and understanding of my father.

Since my dad has a national and international reputation and travels the world speaking and helping people, there were many who thought I would immediately follow in his footsteps. They assumed I'd travel the country speaking, marching, and trying to build my own national reputation. They thought I'd be a young man in a hurry.

I am young, thirty-six, but I'm not in a hurry--except to fix some things in my district. I'm also in a hurry to see the unemployed get jobs; the uninsured get health insurance; the homeless find shelter. But I'm not in a personal hurry. I am willing to take my time, pay my dues, learn my craft--which I see as public service--and earn my seniority. Because I am relatively young in the national political arena, I have the time to grow, to learn, and to develop.

I do not see myself as a politician engaged in public service. I see myself as a public servant engaged in politics. That's an important distinction. For a politician engaged in public service, the thrill is in the politics, the party, the ideology, and the next election. For a public servant, partisanship and ideology become the necessary means to achieving good public policy. Politicians will allow politics, party, and ideology to stand between them and the public good. Public servants owe reasonable loyalty to their party and its beliefs, but ultimately they should not allow that allegiance to supersede doing what is necessary to pass legislation that best serves the interest of the public good.

As long as the people of the Second District of Illinois will have me, I would like to continue to represent them to the best of my ability. If there comes a time, later in my life, for greater national service, I hope to be both knowledgeable and experienced enough to perform the job with dignity, integrity, and excellence.

Looking far ahead in politics, however, is seldom wise, usually risky, and often foolish and dangerous. When I beat Mayor Richard M. Daley's candidate and his machine in the special primary election in 1995, there was immediate press speculation about my challenging Daley and running for mayor of Chicago. It's a fine job, but I have no interest in being the mayor of Chicago.

In 1996, when I criticized Senator Carol Moseley Braun for taking a private trip to Nigeria and becoming too friendly with its dictatorial leadership, the press immediately speculated that I was interested in her job and would challenge her in the 1998 Democratic primary. Nothing could have been farther from my mind.

I think the best approach is to focus on the present, do the best job you can do today for your constituents and the country, and the future will take care of itself. That's why I have done relatively little speaking around the country. My constituents sent me to Congress to represent them, and I do. I've missed only one vote since coming to Congress. I go home to my district virtually every weekend. I accept speaking engagements in my district and hold regular town hall meetings to get input and feedback. If I've been criticized for anything, it's been for focusing too much on my district.

Ford Heights, a city of five thousand just twenty-five minutes from downtown Chicago, had water the color of strong tea. The smelly, polluted water was unfit for bathing, cooking, drinking, or washing clothes. A common sight was children carrying bottled water home from the store. The water was so bad that neighboring fire departments refused to run it through their trucks, because it quickly corroded their equipment. The foul water prevented businesses from locating in this impoverished town--no beauty shops, barber shops, or restaurants. From my first days in the House, I worked to get federal money for a new water tower and infrastructure so that fresh water could finally flow in Ford Heights. Even with a "hurried-up" funding process, I still was not able to get the community safe, fresh water until the summer of 2001--my proudest moment as a congressman.

Ford Heights also has a flooding problem. Every time it rains, and sometimes when it doesn't, Deer Creek floods much of the eastern side of the city, destroying homeowners' furniture and eroding house foundations. Water, sometimes eight inches to a foot deep in the streets, prevents children from going to school or outside to play. The streets are impassable even for cars; workers cannot get to their jobs. Because the town has no money for regular garbage pickup, Deer Creek itself becomes the dump. Adding to this grim picture is the fact that more than three-quarters of Ford Heights residents receive some form of government assistance. Most people cannot fathom such Third World conditions just a stone's throw from a large modern metropolis like Chicago. Improving the lives of the people of Ford Heights remains a top priority of my tenure.

You may have heard of Ford Heights when the story of the "Ford Heights Four" was aired by NBC-TVs Dateline and other TV programs. Four young African American men from Ford Heights--Dennis Williams, Kenneth Adams, Verneal Jimerson, and Willie Rainge--were arrested for allegedly murdering a young white man and his fiancée. They were tried, found guilty, incarcerated, and served eighteen years in prison--including two who served eleven years on death row--only to have a Northwestern University professor and three of his students prove their total innocence through DNA testing in a six-month investigation. The students' investigation turned up shoddy police work, possible criminal misconduct by the local police, and a failure of the Cook County state's attorney to examine police procedures. As yet, no official or office has been held accountable for these wrongful incarcerations.

Other municipalities in my district are nearly as bad off as Ford Heights. In Harvey, the old Dixie Square Mall has stood vacant and failing down since Jake and Elwood, in the movie The Blues Brothers , crashed their way through it on the way to downtown Chicago "on a mission from God." That was the last thing to happen there that generated any revenue. For over twenty-five years, that deteriorating mall has stood as a symbol that our booming economy is not booming for everyone. Industry and workers have fled the area. Consequently, jobs, wages, taxpayers, consumers, schools, and city services have all declined. Today, the abandoned mall is a prime site for rapes, robberies, and drug dealing. The homeless, gangs, and stray dogs often congregate there. And the city of Harvey is so poor that it cannot afford to demolish the unsafe eyesore. Ironically, on one corner of the mall's parking lot rests a brand-new police station with the latest and finest equipment to apprehend the unfortunate young men of Harvey. Getting that mall torn down and working with the people of Harvey and the private sector to build something positive and economically beneficial to the community is another one of my top goals.

Another site that has the potential for economic growth is the 570 acres in southeast Chicago on Lake Michigan that used to be the home of United States Steel. Built in 1881, the huge mill employed almost twenty thousand people in its heyday. Down the street from the site is Bowen High School, which features a large mural in the principal's office depicting the diverse workers--male and female, black, brown, and white--who worked at the U.S. Steel plant for more than a century. The mural seems to be making a statement to students: You, too, can get a good job at the steel plant if you stay in school and do reasonably well. You, too, can raise and provide for your family in this very community if you're willing to work hard. Unfortunately, the mural's message today is as outdated as the old mill's blast furnaces. Since the plant closed in 1992, there have been no comparable jobs available for local students.

Tragically, the mostly African American and Latino student body is not being prepared for the information age and service-based high-tech global economy that is now upon us. With armed police controlling the halls and metal detectors at the entrance, Bowen is hardly an atmosphere conducive to learning.

(Continues...)

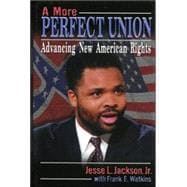

Excerpted from A MORE PERFECT UNION by Jesse L. Jackson, Jr. with Frank E. Watkins. Copyright © 2001 by Jesse L. Jackson, Jr. and Frank E. Watkins. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.