The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

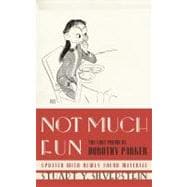

The literary raconteur Alexander Woollcott only intended to fawn over Dorothy Parker when he included the short (eleven-page) but vastly influential profile in his bestselling 1934 essay collection, While Rome Burns. "Our Mrs. Parker" was "a little and extraordinarily pretty woman." Her work was "pure gold" that would be celebrated by future generations. She possessed "the gentlest, most disarming demeanor" while she wielded a verbal "dirk which knows no brother and mighty few sisters." Perhaps she was notorious for stalking human prey, but she loved other animals with a visceral passion. As Woollcott famously explained, Dorothy was "so odd a blend of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth," whose weapon was "not so much the familiar hand of steel in a velvet glove as a lacy sleeve with a bottle of vitriol concealed in its folds."

To illustrate this point, Woollcott catalogued many of the droll and often lethal quips that had been attributed to Dorothy over the preceding fifteen years.I But if Dorothy was already as widely known for her tongue as for her pen, which she was, in later years Woollcott's list would be considered the essential primary source for the thriving literary cottage industry that ultimately overwhelmed any other public reputation that she could ever earn.

I. It is dangerous to ascribe particular anecdotes or witticisms to Dottie. Many are at least partly apocryphal, or are known in several conflicting accounts (each with its own version of parties and dialogue), but conversation is ephemeral, and it is often impossible to determine just who said what. Dottie's contemporaries were particularly vulnerable: as another celebrated wit, the eminent playwright and director George S. Kaufman, dolefully predicted, "Everything I've ever said will be credited to Dorothy Parker." But Woollcott's profile did create an abiding interest in cataloguing Parkerisms when he related the following anecdotes, among many others:Dottie was recuperating in a hospital -- a.k.a. "Bedpan Alley" -- when Woollcott came to visit. Soon after he arrived she rang a bell. He asked if she was calling for drinks. "No, it is supposed to fetch the night nurse, so I ring it whenever I want an hour of uninterrupted privacy."When she heard that an acquaintance had hurt herself in London, Dottie assumed the poor woman must have injured herself sliding down a barrister. And if all the girls who attended the Yale prom were laid end to end, Dottie insisted she would not be at all surprised.Woollcott recalled that the unpopular wife (Mary Sherwood) of a "successful playwright" was forever prattling on about her pregnancy. When the baby was born, Dottie sent her a wire -- collect: GOOD LUCK, MARY. WE ALL KNEW YOU HAD IT IN YOU.Dorothy was only forty years old when the profile appeared. She had published three collections of popular and well-received poetry. She was a prize-winning short-story writer, an influential literary and drama critic, and she was just then negotiating a lucrative contract to write screenplays in Hollywood. But after "Our Mrs. Parker" she was primarily a marketable commodity of distinct proportions: the tiny woman with the big mouth who knew the gamut from A to B and wrote irreverent reviews that sounded as though she was still at the Algonquin Round Table; the one who also wrote a few poems, short stories, and film scripts whose titles were not quite so memorable as one might presume; the one who survived those abortions and suicide attempts and wretched affairs along the way and whose life often made her want to fwow up.

The ambitious artist was even degenerating into stock literary and theatrical cliche. In 1932, two years before the Woollcott profile, Dorothy was the model for "Lily Malone" in Philip Barry's play Hotel Universe. In Barry's description, Lily was "able to impart to her small, impudent face a certain prettiness." Also in 1932, Dorothy was "Mary Hilliard" in George Oppenheimer's Here Today, which was directed by George S. Kaufman, a former Algonquin colleague with whom Dorothy usually shared a cordial mutual contempt.

In 1934, the year the Woollcott piece appeared, "Dorothy" starred as the dowdy "Julia Glenn" in the Kaufman-Moss Hart comedy Merrily We Roll Along. Julia was "a woman close to forty. She is not unpretty, but on her face are the marks of years and years of quiet and steady drinking -- eight, ten hours a day." Also in 1934, she was the nightclub singer "Daisy Lester" in Charles Brackett's novel Entirely Surrounded. Brackett described her as "a tiny, dark figure in a blue dress with peasant embroidery on the sleeves." He even dedicated the book to her. And in 1944, she surfaced again as "Paula Wharton" in Over Twenty-one, a play written by the actress Ruth Gordon and again directed by Kaufman.2 The die was cast. Dorothy Parker was famous for being Dorothy Parker, and that was what she always would be. And in the popular consciousness, she could never be anything more.

2. Dottie was not pleased by the sincerest form of flattery: "I suppose that now if I ever wrote a play about myself, I'd be sued for plagiarism ."Another time, Dottie met a playwright she thought was appropriating some of her ideas. He said that his next work was a "play against all isms." Dottie: "Except plagiarism."Dorothy Rothschild3 was born, prematurely, on August 22, 1893, in West End, New Jersey.4 Her mother, Eliza nee Marston, was of English ancestry, and her father, Jacob Henry Rothschild, who preferred to be known by his middle name, came from Prussian Jewish stock. Henry was a partner in a prosperous cloak-making firm, and the family lived a comfortable life with servants in an exclusive neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

3. Dottie later confessed: " My God, no, dear! We'd never even heard of those Rothschilds!"4. Dottie: "I was cheated out of the distinction o f being a native New Yorker, because I had to go and get born while the family was spending the summer in New Jersey, but, honestly, we came back to N ew York right after Labor Day, so I nearly made the grade."A month before Dorothy's fifth birthday, she was devastated when Eliza "promptly went and died" on her. Henry quickly found a new wife, Eleanor Lewis, who was in Dorothy's words "crazy with [presumably Presbyterian] religion." Dorothy later claimed to so dislike her that she could only address Eleanor as "hey, you" because she could not bear to call her Mother. Eleanor died three years later, when Dorothy was still only nine years old. Dorothy later described an implausibly grim existence that included such standard elements as the distant father and the wicked stepmother, but more prosaically, she was the "artistic" child who wrote verses and loved the assortment of dogs that the family had started adopting and quickly spoiling. She retained her love of undisciplined dogs and most other creatures for the rest of her life.5

5. In later life Dottie had a dog called Woodrow Wilson. Woodrow suffered from what Aleck Woollcott delicately described as a "distressing malady." According to Dottie, the dog said he got it from a lamppost. She later adopted an amiable dachshund called Robinson. Robinson was attacked in the street by a much larger dog whose owner claimed that Robinson had started it. Dottie was incredulous: "I have no doubt that he was also carrying a revolver."Once Dottie brought her dog to a party, where it vomited on the rug. Dottie tried to apologize, or at least explain, to her hostess: "It's the company." Another time her dog relieved itself in the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel. The hotel manager scolded her: "Miss Parker, Miss Parker! Look what your dog did." Dottie stared at him: "I did it." And she walked away.Dottie's record with other animals was less commendable, though she once had a parakeet she called Onan. Why? See Genesis 38:9. But on another occasion a friend asked her how he could get rid of his cat. Dottie: "Have you tried curiosity?"By the time Dorothy was twelve she was four feet eleven inches tall. She was excessively thin and would remain underweight until she was in her twenties, a fact that she would recall nostalgically, and ruefully, in later years. She had a heart murmur. If she intuitively felt isolated from her world, the schools she attended made her feel worse. At a time when a Rothschild was a Jew and was treated accordingly, Dorothy was enrolled first in a Catholic elementary school, where she often had trouble with the nuns,6 and then in a restricted Protestant high school (her father lied on the application). She left the high school six months later, when she was fourteen, and did not return. During her abbreviated education Dorothy learned Latin and French and developed a keen appreciation of literature and poetry, but in later years she avoided admitting that she had never graduated from high school.7

6. She later argued: "Well, how do you expect them to treat a kid who saw fit to refer to the Immaculate Conception as 'Spontaneous Combustion'? Boy, did I think I was smart! Still do."7. Dottie: "The only thing I ever learned [in school] that ever did me any good in after life was that if you spit on a pencil eraser, it will erase ink."After leaving school she moved in with her father for six increasingly grim years. Henry suffered financial reverses, grew ill, and finally died in 1913, when he was sixty-two and Dorothy was twenty. Though he probably bequeathed a small estate to his four children (Dorothy was the youngest), he did leave something: Dorothy later claimed that she had been left penniless.

In 1914, she found work as a dance instructor while she yearned for the literary life. She experimented with light verse and sold a piece to the famously urbane Frank Crowninshield, who had recently been appointed the editor of the new Vanity Fair magazine by the publisher Conde Nast. In nine repetitive stanzas, "Any Porch" casually dissected the meandering conversations of banal upper-middle-class women who had reached a certain age. Dorothy was paid twelve dollars for the piece and received her first known credit when Vanity Fair published it in September 1915. Perhaps of greater importance, Crowninshield found himself amused by the callow but promising young talent and, at Dorothy's urgent request, found her a ten-dollar-a-week job writing captions at Vanity Fair's sister publication, Vogue.8

8. More than forty years later, Dottie recalled the exhilaration of landing that first literary job on Vogue: " Well, I thought I was Edith Sitwell."But working for Vogue in 1914, and for forty years thereafter, meant working under the exceedingly proper Edna Woolman Chase, who enforced a strict dress code that included white gloves but prohibited open-toed shoes, and maintained a formidably rigorous standard of decorum. For example, when an editor who had attempted suicide returned to work, Mrs. Chase called her in and told her: "We at Vogue don't throw ourselves under subway trains, my dear. If we must, we take sleeping pills."

Dorothy was often a deliberately disruptive force who did not mesh well with the rest of the Vogue staff and particularly did not get on with Mrs. Chase.9 Though Mrs. Chase did try to utilize her talents,10 even publishing a verse titled "The Lady in Back" in November 1916, and though Dorothy volunteered for several weird experiments, including a risky new process called a permanent wave, they both realized that Dorothy belonged somewhere else. In the fall of 1917, she moved down the hall to Crowninshield's Vanity Fair.

9. Dottie was astounded, but hardly speechless, the first time she saw the ornate Vogue offices: "Well, it looks just like the entrance to a house of ill-fame."She wrote this caption for an underwear layout: "From these foundations of the autumn wardrobe, one may learn that brevity is the soul of lingerie, as the Petticoat said to the Chemise." That line actually appeared in the magazine, but the proofreaders caught and scrapped her caption for a photograph of a model wearing an expensive nightgown that suggested commercial, as well as romantic, considerations: "There was a little girl who had a little curl, right in the middle of her forehead. When she was good she was very, very good, and when she was bad she wore this divine nightdress of rose-colored mousseline de soie, trimmed with frothy Valenciennes lace."10. When Mrs. Chase allowed her to write feature stories, Dottie tried to twist the focus to embarrass her subjects, i.e., her piece on interior decoration used a fictional profile that ridiculed an hysterical and flamboyantly homosexual decorator. The piece was titled "Interior Desecration."She had been submitting poems and verses to Vanity Fair for years. None were particularly good: the next three that Crowninshield published, "The Bridge Fiend," "A Musical Comedy Thought," and "The Gunman and the Debutante," had clever moments but still displayed more potential than competence. And one of them could have destroyed her career.

"A Musical Comedy Thought" was published in the June 1916 issue of Vanity Fair. It described, with tongue firmly in cheek, a bizarre but popular vaudeville singer who impersonated women both in voice and couture. But then Franklin P. Adams, the distinguished F. P. A . of the New York Tribune, got involved. Adams was New York's preeminent columnist. He also dabbled in poetry and published several highly regarded collections of light verse, which included "Baseball's Sad Lexicon," more familiarly known as "Tinker to Evers to Chance." Nearly every day his Conning Tower column published submissions from readers who wanted to display their talents publicly, and the gold watch he gave each year for the best poem was one of New York's most valued literary prizes. It was the mighty Adams who, on May 23, 1916, took notice of young Dorothy Rothschild when he started his column with Dorothy's verse:

Adams followed it with his own devastating response:

Hammond, then a Chicago Tribune theater critic, had once described Eltinge as "ambisextrous." Both Adams's contemptuous dismissal and Dorothy's reaction to it are lost to history. There appears to be no record of the exchange outside the old Conning Tower clippings, and though there is no evidence that either Dorothy or Adams ever mentioned it again, it must have been a crushing blow to her. She was only twenty-two, with a tenuous hold on an entry-level literary job, and was desperately trying to make a name for herself in that world. Instead, her first substantial public recognition was as a plagiarist, and a notably clumsy one at that.

Dorothy had at least two similar but vastly less serious brushes with Adams in later years. In 1914, Adams had hailed Dulcinea, a popular character in The Conning Tower, with "Dulcy far niente," a pun on the Italian "dolce far niente," loosely translated as "pleasant idleness." Seven years later, in November 1921, Dorothy borrowed it for "Lynn Fontanne," a verse saluting the star of the hit George S. Kaufman -- Marc Connelly comedy Dulcy, which was based on the same character. Although Adams surely recalled his earlier sally -- he had a fabulous memory -- he did not publicly comment on her appropriation. But he did preen while writing "To Dorothy Parker" in The Conning Tower, by then in The (New York) World, on December 18, 1922:

It is likely that Adams was jocularly comparing the compellingly dreary title character in May Sinclair's The Life and Death of Harriett Frean, which had been published earlier that year, and the stock literary figure described in Dorothy's verse "The Drab Heroine," which had appeared in the March 9, 1922, issue of Life magazine. But that was all far in the future when, in mid 1916, Dorothy must have felt severely chastened and was fretfully considering her next step.

She probably had been experimenting with free verse for some time before succumbing to her caustic instincts and finding that she enjoyed writing screeds. The result was a piece called "Women: A Hate Song," a broad and extended diatribe listing the alleged faults of her own sex. Dorothy submitted it to Crowninshield under the name "Henriette Rousseau";11 he loved it and put it in the August 1916 issue, to great popular enthusiasm. Crowninshield asked her for more diatribes, and over the next eight years Dorothy produced seventeen more so-called "hate verses" for both Vanity Fair and Life, skewering, among other targets, husbands and wives, actors and actresses, books, theater, and film. The series spawned numerous of imitators.

11. Years later she signed some pieces "Helen Wells," probably a play on "Hell on Wheels"That summer, Dorothy fell in love with Edward Pond Parker II, a tall, fair stockbroker of her own age from an old Connecticut Congregationalist family. She may have conducted desultory affairs with similar men before -- she always liked athletes with good (i.e., northwest European)12 features -- but, she admitted forty years later, Eddie was "beautiful." He was also "not very smart. He was supposed to be in Wall Street, but that didn't mean anything."

12. Years later, she ruefully described her "type": "I require only three things of a man. He must be handsome, ruthless, and stupid."When the United States entered the First World War in April 1917, Eddie enlisted in the army and proposed marriage. As Eddie's family disapproved of the match, and Dorothy had already distanced herself from her own family, neither side attended the June ceremony. Soon Eddie was off to train to be an ambulance driver.13 While he was in France, Dorothy kept the home fires burning by writing hate verses about bohemians and slackers who were not pulling their weight in the war effort.

13. Dottie: "We were married for about five minutes, then he went off to war."Dorothy finally found a home at Vanity Fair. Crowninshield hoped to bring about a revival of Good Taste -- it was said that his "mind was cultivated rather than profound" -- and his purportedly frothy magazine was one of the most beautiful, yet aesthetically adventurous, publications of that or any era, on the very cusp of the avant-garde. During his first fifteen years there (during the sixteenth year he helped establish the Museum of Modern Art), Vanity Fair introduced a blinding array of new talent to the mass American public: "his" writers included Dorothy, Robert Benchley, P. G. Wodehouse, Edna St. Vincent Millay, e. e. cummings, and Aldous Huxley. Crowninshield took particular pride in Vanity Fair's visual "look," which often startled traditional sensibilities. Though he brought artists such as Rockwell Kent, Pablo Picasso, and Miguel Covarrubias to public attention, Crowninshield ruefully observed in 1928 that "the new artists whom we have periodically presented have aroused the greater part of the criticism that Vanity Fair has had to combat from time to time." Crowninshield also employed photographers such as Baron de Meyer and Edward Steichen "when their work was branded as wild and absurd."

Dorothy worked as a general editorial assistant for several months, but when Wodehouse took a leave of absence Crowninshield made her New York's only female drama critic. She started her column in the April 191 8 issue and, as with the hate verses, she found she often preferred inflicting abuse to tendering praise.14 She was amusing, she was witty, she was wicked, and she was noticed. People started talking about that devilish Mrs. Parker.

14. Though most of her reviews were innocuous, there were notable exceptions. In her very first column, in April 1918, she suggested attending Girl 0' Mine "if you want a couple of hours' undisturbed rest. If you don't knit, bring a book." As to The Love Mill, "I know who wrote those lyrics and I know the names of the people in the cast, but I 'm not going to tell on them." Sinbad, she concluded, was "produced in accordance with the fine old Shubert precept that nothing succeeds like undress," which was, at least, an improvement over the production whose chorus line appeared to be composed of "kind, motherlylooking women."In November the war ended, but Eddie remained in Europe with the occupation forces. Dorothy continued reviewing plays and submissions while Crowninshield looked for a managing editor. He found an apparently prim and reserved twenty-nine-yearold teetotaler who had written some of the looniest pieces Crowninshield had ever read, and eventually offered him the job. On May 19, 1919, Dorothy arrived at work to meet Robert Benchley: he introduced himself to "Mrs. Parker," she extended her greetings to "Mr. Benchley," and they went to work.

A few days later Crowninshield brought in their new "drama editor," with unspecified duties: a young (twenty-three) and astonishingly tall (six-foot-seven) veteran of the Canadian Black Watch regiment called Robert Sherwood. If Benchley was reticent, Sherwood was silent -- so quiet, in fact, that he scared his new coworker's.15 It turned out that Sherwood was very shy, and when he finally loosened up, the three quickly became close friends.

15. Dottie warned Benchley that Sherwood was a "Conversation Stopper," i.e., similar to "riding on the Long Island Railroad -- it gets you nowhere in particular."Copyright © 1996 by StuartY. Silverstein