KESARBAI

We sat inside the stuffy room, windows closed to keep out the torrential rain. I was trying to swat a fly which dashed in for shelter and was buzzing around psychotically. Dhondutai watched me and laughed softly. ‘Leave the poor thing. Come let’s make some tea and relax,’ she said. ‘What other choice do we have? You can leave when the rain slows down. Until then, why don’t we listen to some music recordings?’

‘Good idea, baiji.’

We went into her kitchen and I watched the ritual that had intrigued me for the past twenty years. I knew each object so well—the electric lighter she double-clicked to fire up the stove, the rusted green tin filled with aromatic tea leaves, the chipped cup that had faithfully accompanied her from one home to another. She mixed two kinds of tea leaves and left them to steep for a few minutes. ‘My tea is like a combination raga. Both individually great tasting, but when melded together just right, what a superb result!’

I smiled. Coming to Dhondutai had become a habit I could not break. I was now married, had moved back to Bombay, and reported on personal finance for The Times of India. In between all this, I still took the fast train to Borivli, and continued to weather jokes about my irrational obsession. It was a parallel world that had absolutely no connection with the rest of my life. I found solace in her small universe.

Dhondutai continued to harbor dreams of turning me into a great singer. And I? I tried, but could not devote the time, the unconditional commitment it takes, and kept faltering; missing my lessons because of a late night, one cigarette too many, or a work deadline.

Yet, something had definitely changed for me. I had begun to understand the power of this music. It had entered me. When I sang, I lost myself and my sense of time. My music lesson, and Dhondutai’s unconditional love, had become my therapy.

I picked up the cups of steaming tea and proceeded to the music room which had earned its lofty title because it was equipped with a two-in-one cassette player and a cupboard which housed Dhondutai’s music, recorded over the years. She gingerly took out a cardboard box containing an assortment of tapes—Sony, TDK, Aiwa—and I picked one out at random. The barely legible writing scrawled across the header read: Dadar-Matunga Cultural Centre, 1976.

I pressed play and a scratchy noise filled the speakers before Dhondutai’s voice came on and started to gradually unravel Raga Bihagda. We listened silently for a few minutes. It was a beautiful composition. I softly exclaimed ‘wah’ every time she completed her cycle with a flourish, and enjoyed her beam at my appreciation.

‘Who taught you this, baiji?’

‘Kesarbai. It was one of her favorite ragas. In fact, this is what she sang the first time I met her.’

‘Tell me about that, please?’

Dhondutai laughed. ‘Just listen to the music. That is more relevant!’

‘Please, baiji, come on! I’m sure there’s a great story there…’

‘You are mad! Anyway, if you insist.’ She put down her cup and proceeded, in all seriousness. ‘I first met her in 1962. The only other time I had seen her was in 1944 at the Vikramaditya Conference. She was performing at the Birla Matoshree Hall near Marine Lines and the three of us bought tickets and went to listen.’

‘Who three?’

‘Why, my father, me and Baba…’

‘Ok, please continue … Wah!’ My attention was momentarily diverted by the music. She had just sung a brilliant passage, playing on the words of the song. I heard exclamations from the audience which had also been recorded. This was the beauty of live performance. Great music was complete only when the notes from the performer touched the soul of the listener and the sigh of appreciation went back to the musician. This connection was like an electric current. In fact, in the days when music was performed in intimate concert halls, the area in front of the stage was usually reserved for what was described as the ‘wah-wah group’—listeners who made it a point to respond to the artist with loud approval, sighs and gestures.

The mellow music, this particular raga, the memories that were softly bubbling to the surface, all made Dhondutai warm up to the conversation, and she described her first meeting with the demonic singer who had once guided these notes and taught her how to please the deity inside ga, the dominant swara of Raga Bihagda.

‘I think I was about thirty years old, actually a little older,’ she started.

‘About my age,’ I murmured.

‘Yes, but unlike you, I was not a foolish dilettante. I took my learning seriously,’ she said, with no rancour. I grinned sheepishly, in agreement.

‘Yes, so we took the overnight train from Jabalpur to Bombay after Baba read an interview with Kesarbai in a Marathi newspaper where she said that she was finally ready to teach a student who would be worthy of her… ’

Baba knew that for Dhondutai to take the music of his gharana forward, Bhurji Khan’s training was not enough. He had to introduce Dhondutai to the gharana’s most gifted singer. Besides, he could see that his musical sister was languishing in Jabalpur, where she had been living for the last five or six years. Soon after Bhurji Khan died, Dhondutai and her sister had moved to Hyderabad to help their uncle Shankarrao with his ayurvedic company. Seven years later, after a small tiff with the uncle, the whole family moved to Jabalpur where Dhondutai’s sister got married, and her brother got his first job. Although she kept up her singing, and gave regular radio concerts, Dhondutai was fading away. Places like Hyderabad and Jabalpur were not musical centres. She needed to be in the big city, beneath the stage lights.

* * *

In the fifties and sixties, Birla Matoshree Hall was among the most prestigious auditoriums in the city. Dhondutai, Ganpatrao and Baba walked down the marble stairs, past two enormous busts of the patrons, towards the green room. Father and daughter waited outside while Baba went inside.

There, seated on a chair, with a square halo of glaring bulbs on the mirror behind her, sat Kesarbai. She had the poise of a queen, but sat like a king, her legs slightly apart, her hands on her thighs. She was wearing her signature white silk sari. Large solitaires sparkled in her ears and pearls gleamed on her neck. Seated on the floor around her was her usual coterie—her good friend Shantibhai, her sarangi player Abdul Majid Khan, whose off-white kurta shirt was already bedecked with tiny flecks of crimson betel juice, and Yeshwant Kerkar, who accompanied her on the tabla. These two musicians had loyally accompanied her year after year, and she had taken good care of them so that they did not play with any of her rivals. This was part of her elaborate copyright protection strategy. After all they knew her music more intimately than any one else.

Baba greeted the musicians, touching his hand to his forehead in the customary salute. ‘Mai, how are you?’ Then he turned to the accompanists. ‘Aadaab, Khansahib. Namashkar panditji.’

‘Arre, Baba! How good to see you. When did you come from Kolhapur? How is your mother? Come in. Come in.’ Kesarbai pulled a comb out of her purse, peered at the mirror, and delicately smoothed her eyebrows.

‘Mai, I have brought Dhondutai, Abbaji’s student, who had written to you. Would you be agreeable to let her sit behind you on stage today?’

Kesarbai stared at him for a few seconds, with a scalding look that would have burned a hole through one not already familiar with her manner. ‘Hmph. Let’s see what Bhurji has produced. Bring her in.’

Baba went outside with a grin and told Dhondutai to come in. Father and daughter entered hesitantly. Dhondutai looked at Ganpatrao for approval, touched Kesarbai’s feet and stood with her hands clasped together, her gait confident but respectful. Kesarbai looked her up and down. ‘So, you think you will be able to accompany me?’

‘I’ll try, mai. It depends on whether I know the raga you are singing,’ Dhondutai replied.

‘Of course you know it. I am singing Bihagda. These days, the whole world claims to know Bihagda. Even the low-life bitch who cleans Alladiya Khan’s toilets can sing Bihagda. Why won’t you be able to sing it?’ She guffawed and looked at Majid Khan. ‘What do you say, khansahib?’ He chuckled back at her. Baba smiled uncomfortably and tried not to look at Ganpatrao to see his reaction.

In one stupendous flourish, Kesarbai confirmed all the rumours about her being an outspoken woman with a filthy tongue. Dhondutai was mortified, but from that moment on, she decided that she would not be distracted by Kesarbai’s personality. She was there for only one thing. She would single-mindedly focus on that and ignore the rest.

Later that evening, Kesarbai, siting between two tanpuras, presented the kind of music that a listener gets to hear only once or twice in a lifetime rendering one extraordinarily beautiful raga after another. Her music had the quality of an uncut diamond. It was raw, sometimes even rough, yet gorgeous. After she finished the last note and the tanpuras stilled, there was a moment of absolute silence before the audience broke into applause. It was clear. No matter how egoistic or ill-mannered she was, when this woman sat down to sing, she was transformed into something higher than her mortal self. Sitting behind her, Dhondutai decided that she desperately wanted a part of this magic.

* * *

The tape ended with a soft click. Dhondutai touched her ears and shook her head with a shudder. ‘You have no idea what used to come out of her mouth. What a woman!’ She paused and added, ‘Actually, she was more like a man...’

I had heard so much about this intrepid woman who had more enemies than friends. The stories are legendary—like the time she won the Padma Vibhushan. Kesarbai was walking down the steps of the president’s office in Delhi, when she ran into Indira Gandhi, who was then Prime Minister of India. They greeted each other respectfully. After exchanging pleasantries, Mrs Gandhi requested Kesarbai to place her hand on her throat. She said that the touch of a great singer would ensure that her voice would always be in good shape. Kesarbai retorted, with a laugh: ‘Your voice seems fine, madam. You shout quite a bit already,’ and sailed past the stunned Prime Minister.

Another time, she was asked to perform at a programme to celebrate the formation of the state of Maharashtra in 1960. After she sang, Chief Minister Yeshwantrao Chavan went up to her and said, ‘Ask for anything and it will be yours.’

‘Are you sure,’ she said, her eyes twinkling.

‘Of course, Kesarbai. Today is a historic day for the city and for the people of Maharashtra. And you have graced the occasion with your tremendous art.’

‘Then give me your office for one day.’

The chief minister kept his cool. ‘What will you do with it, Kesarbai? Do tell me, and I shall try and implement what you have in mind.’

Kesarbai laughed and said, ‘Never mind. But next time, don’t make promises you cannot keep!’

When Dhondutai lay down to nap, I went into the other room and stared at the portrait of the woman with the voice of a man; a woman whose temper had once prompted a wealthy Bombay businessman to crawl under the creaky wooden stage and sit in hiding for two hours so that he could listen to her music, because she had banished him from attending her concerts after they had had a tiff.

Kesarbai was known for her tempestuous outbursts in public. She would scrutinize her audience like a hawk and ensure that none of her ‘enemies’ was present. If someone made the mistake of coughing while she was singing, and she happened to be in a bad mood, she would stop in the middle of her performance and order the hapless listener to leave the auditorium.

Why was she so mean spirited, yet so gifted? So narcissistic and self-destructive? How did these base traits exist in conjunction with her sublime art? Or could it be the other way around? That to achieve that level in music, or any creative endeavour, demands an element of mania? I found, as I entered her world, that Kesarbai’s determination to become a great singer—the best in the world—was not a spiritual quest. Rather, it was driven by vengeance, and rooted in unimaginable pain.

* * *

It was 1914. A lavish feast was underway. Two wellknown Marathi families were joining in matrimony through their children Hirabai and Anantrao. The men strolled into the hall from the front entrance, greeting one another jovially. The women, as was the custom, came in from the back and stayed there, hovering around the bride, commenting on her jewellery, gossiping about the decor. As the men sat around sipping sandalwood sherbet, they were surprised to see a young woman amble in through the front gate. She must have been in her early twenties. She wore a silk sari with a sleeveless blouse. Her eyes were lined with kohl, her lips faintly stained with betel leaf. Her neck glistened with a gold necklace. There was no shawl of modesty wrapped around her shoulders which was customary among women in those days. She didn’t pay attention to any one, but was conscious of the eyes on her, some lascivious, others merely curious. She glided jauntily into the women’s enclosure. An audible murmur went around the party of men and one of them got up, strode inside and whispered something into his wife’s ear. A few minutes later, the groom’s mother called the bride’s mother aside.

‘Who is that woman?’

‘Her name is Kesar. She is one of our tenants. She lives in the building across ours.’ Hirabai’s mother did not dare reveal that the pretty young guest was quite friendly with her daughter. Or, that they would holler and squeal at each other from their windows, even if they were separated by an unbridgeable social chasm.

‘Well, clearly, she does not belong here. Women like that should not be at functions like ours. We are Brahmins. What will people say…’ hissed the mother of the groom.

‘Tai. What do you want me to do? I can’t possibly ask her to leave now that she is here. That would be deeply insulting.’

‘It would be far more inauspicious for her to stay. The ceremony is exactly half an hour away. If you still want the wedding to take place, please make sure she is not here. The choice is yours.’

The hostess hurriedly went and whispered something in the young woman’s ear. Kesar stared at the older woman in disbelief. Her kohl-lined eyes filled up but she did not allow even a drop to escape. Then, without saying a word, she got up and left.

As she walked home crying in the noonday sun, the enraged young woman swore to herself that one day, she would make this very gentry pine for her.

She did—she became the great Kesarbai Kerkar. But the stigma that surrounded ‘singing women’ was not about to disappear very quickly. It festered in the hearts of a patriarchal society, which enjoyed its women entertainers but didn’t want them mingling with their daughters.

In fact, even fifty years later, people harboured the same feelings about this community. Long after Kesarbai had established herself as a great diva, and long after India had entered an era of so-called modernity, when her granddaughter Il was getting married in the nineteen seventies, she faced similar murmurs of outrage because of her lineage. It didn’t matter that the bride’s grandmother was one of the greatest singers India had ever heard. She was, after all, a ‘bai,’ from the courtesan community.

* * *

There are numerous stories about singers like Kesarbai who, despite their artistic achievements, had to silently endure the slights and humiliations flung at them. Gohar Jaan was one of the most formidable women singers of the early nineteen hundreds. She dressed and lived like a queen. She used to wear an invaluable diamond brooch on her left shoulder, which is why she always had two rifle-wielding soldiers stand guard on either side of her while she performed. Once, in Calcutta, she had gone for a ride in a carriage led by four majestic horses. The British governor, who happened to ride past her, automatically saluted her, assuming she was royalty. He was later told that the person in the carriage was a ‘singing girl’. He was so livid that he had shown respect to a mere courtesan, that he passed an edict declaring that no one besides royalty could use a fourhorse carriage.

The fact that Gohar Jaan was the reigning queen of music in India was not pertinent to her social status, especially in the eyes of men. They may have plied her with pearls and promises in their weak moments, but at the end of the day, she was deemed a woman of disrepute. This was the paradox most women singers lived with.

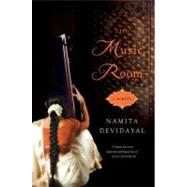

Copyright © 2007 by Namita Devidayal. All rights reserved.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

KESARBAI

We sat inside the stuffy room, windows closed to keep out the torrential rain. I was trying to swat a fly which dashed in for shelter and was buzzing around psychotically. Dhondutai watched me and laughed softly. ‘Leave the poor thing. Come let’s make some tea and relax,’ she said. ‘What other choice do we have? You can leave when the rain slows down. Until then, why don’t we listen to some music recordings?’

‘Good idea, baiji.’

We went into her kitchen and I watched the ritual that had intrigued me for the past twenty years. I knew each object so well—the electric lighter she double-clicked to fire up the stove, the rusted green tin filled with aromatic tea leaves, the chipped cup that had faithfully accompanied her from one home to another. She mixed two kinds of tea leaves and left them to steep for a few minutes. ‘My tea is like a combination raga. Both individually great tasting, but when melded together just right, what a superb result!’

I smiled. Coming to Dhondutai had become a habit I could not break. I was now married, had moved back to Bombay, and reported on personal finance forThe Timesof India. In between all this, I still took the fast train to Borivli, and continued to weather jokes about my irrational obsession. It was a parallel world that had absolutely no connection with the rest of my life. I found solace in her small universe.

Dhondutai continued to harbor dreams of turning me into a great singer. And I? I tried, but could not devote the time, the unconditional commitment it takes, and kept faltering; missing my lessons because of a late night, one cigarette too many, or a work deadline.

Yet, something had definitely changed for me. I had begun to understand the power of this music. It had entered me. When I sang, I lost myself and my sense of time. My music lesson, and Dhondutai’s unconditional love, had become my therapy.

I picked up the cups of steaming tea and proceeded to the music room which had earned its lofty title because it was equipped with a two-in-one cassette player and a cupboard which housed Dhondutai’s music, recorded over the years. She gingerly took out a cardboard box containing an assortment of tapes—Sony, TDK, Aiwa—and I picked one out at random. The barely legible writing scrawled across the header read: Dadar-Matunga Cultural Centre, 1976.

I pressed play and a scratchy noise filled the speakers before Dhondutai’s voice came on and started to gradually unravel Raga Bihagda. We listened silently for a few minutes. It was a beautiful composition. I softly exclaimed ‘wah’ every time she completed her cycle with a flourish, and enjoyed her beam at my appreciation.

‘Who taught you this, baiji?’

‘Kesarbai. It was one of her favorite ragas. In fact, this is what she sang the first time I met her.’

‘Tell me about that, please?’

Dhondutai laughed. ‘Just listen to the music. That is more relevant!’

‘Please, baiji, come on! I’m sure there’s a great story there…’

‘You are mad! Anyway, if you insist.’ She put down her cup and proceeded, in all seriousness. ‘I first met her in 1962. The only other time I had seen her was in 1944 at the Vikramaditya Conference. She was performing at the Birla Matoshree Hall near Marine Lines and the three of us bought tickets and went to listen.’

‘Who three?’

‘Why, my father, me and Baba…’

‘Ok, please continue … Wah!’ My attention was momentarily diverted by the music. She had just sung a brilliant passage, playing on the words of the song. I heard exclamations from the audience which had also been recorded. This was the beauty of live performance. Great music was complete only when the notes from the performer touched the soul of the listener and the sigh of appreciation went back to the musician. This connection was like an electric current. In fact, in the days when music was performed in intimate concert halls, the area in front of the stage was usually reserved for what was described as the ‘wah-wah group’—listeners who made it a point to respond to the artist with loud approval, sighs and gestures.

The mellow music, this particular raga, the memories that were softly bubbling to the surface, all made Dhondutai warm up to the conversation, and she described her first meeting with the demonic singer who had once guided these notes and taught her how to please the deity inside ga, the dominant swara of Raga Bihagda.

‘I think I was about thirty years old, actually a little older,’ she started.

‘About my age,’ I murmured.

‘Yes, but unlike you, I was not a foolish dilettante. I took my learning seriously,’ she said, with no rancour. I grinned sheepishly, in agreement.

‘Yes, so we took the overnight train from Jabalpur to Bombay after Baba read an interview with Kesarbai in a Marathi newspaper where she said that she was finally ready to teach a student who would be worthy of her… ’

Baba knew that for Dhondutai to take the music of his gharana forward, Bhurji Khan’s training was not enough. He had to introduce Dhondutai to the gharana’s most gifted singer. Besides, he could see that his musical sister was languishing in Jabalpur, where she had been living for the last five or six years. Soon after Bhurji Khan died, Dhondutai and her sister had moved to Hyderabad to help their uncle Shankarrao with his ayurvedic company. Seven years later, after a small tiff with the uncle, the whole family moved to Jabalpur where Dhondutai’s sister got married, and her brother got his first job. Although she kept up her singing, and gave regular radio concerts, Dhondutai was fading away. Places like Hyderabad and Jabalpur were not musical centres. She needed to be in the big city, beneath the stage lights.

* * *

In the fifties and sixties, Birla Matoshree Hall was among the most prestigious auditoriums in the city. Dhondutai, Ganpatrao and Baba walked down the marble stairs, past two enormous busts of the patrons, towards the green room. Father and daughter waited outside while Baba went inside.

There, seated on a chair, with a square halo of glaring bulbs on the mirror behind her, sat Kesarbai. She had the poise of a queen, but sat like a king, her legs slightly apart, her hands on her thighs. She was wearing her signature white silk sari. Large solitaires sparkled in her ears and pearls gleamed on her neck. Seated on the floor around her was her usual coterie—her good friend Shantibhai, her sarangi player Abdul Majid Khan, whose off-white kurta shirt was already bedecked with tiny flecks of crimson betel juice, and Yeshwant Kerkar, who accompanied her on the tabla. These two musicians had loyally accompanied her year after year, and she had taken good care of them so that they did not play with any of her rivals. This was part of her elaborate copyright protection strategy. After all they knew her music more intimately than any one else.

Baba greeted the musicians, touching his hand to his forehead in the customary salute. ‘Mai, how are you?’ Then he turned to the accompanists. ‘Aadaab, Khansahib. Namashkar panditji.’

‘Arre, Baba! How good to see you. When did you come from Kolhapur? How is your mother? Come in. Come in.’ Kesarbai pulled a comb out of her purse, peered at the mirror, and delicately smoothed her eyebrows.

‘Mai, I have brought Dhondutai, Abbaji’s student, who had written to you. Would you be agreeable to let her sit behind you on stage today?’

Kesarbai stared at him for a few seconds, with a scalding look that would have burned a hole through one not already familiar with her manner. ‘Hmph. Let’s see what Bhurji has produced. Bring her in.’

Baba went outside with a grin and told Dhondutai to come in. Father and daughter entered hesitantly. Dhondutai looked at Ganpatrao for approval, touched Kesarbai’s feet and stood with her hands clasped together, her gait confident but respectful. Kesarbai looked her up and down. ‘So, you think you will be able to accompany me?’

‘I’ll try, mai. It depends on whether I know the raga you are singing,’ Dhondutai replied.

‘Of course you know it. I am singing Bihagda. These days, the whole world claims to know Bihagda. Even the low-life bitch who cleans Alladiya Khan’s toilets can sing Bihagda. Why won’t you be able to sing it?’ She guffawed and looked at Majid Khan. ‘What do you say, khansahib?’ He chuckled back at her. Baba smiled uncomfortably and tried not to look at Ganpatrao to see his reaction.

In one stupendous flourish, Kesarbai confirmed all the rumours about her being an outspoken woman with a filthy tongue. Dhondutai was mortified, but from that moment on, she decided that she would not be distracted by Kesarbai’s personality. She was there for only one thing. She would single-mindedly focus on that and ignore the rest.

Later that evening, Kesarbai, siting between two tanpuras, presented the kind of music that a listener gets to hear only once or twice in a lifetime rendering one extraordinarily beautiful raga after another. Her music had the quality of an uncut diamond. It was raw, sometimes even rough, yet gorgeous. After she finished the last note and the tanpuras stilled, there was a moment of absolute silence before the audience broke into applause. It was clear. No matter how egoistic or ill-mannered she was, when this woman sat down to sing, she was transformed into something higher than her mortal self. Sitting behind her, Dhondutai decided that she desperately wanted a part of this magic.

* * *

The tape ended with a soft click. Dhondutai touched her ears and shook her head with a shudder. ‘You have no idea what used to come out of her mouth. What a woman!’ She paused and added, ‘Actually, she was more like a man...’

I had heard so much about this intrepid woman who had more enemies than friends. The stories are legendary—like the time she won the Padma Vibhushan. Kesarbai was walking down the steps of the president’s office in Delhi, when she ran into Indira Gandhi, who was then Prime Minister of India. They greeted each other respectfully. After exchanging pleasantries, Mrs Gandhi requested Kesarbai to place her hand on her throat. She said that the touch of a great singer would ensure that her voice would always be in good shape. Kesarbai retorted, with a laugh: ‘Your voice seems fine, madam. You shout quite a bit already,’ and sailed past the stunned Prime Minister.

Another time, she was asked to perform at a programme to celebrate the formation of the state of Maharashtra in 1960. After she sang, Chief Minister Yeshwantrao Chavan went up to her and said, ‘Ask for anything and it will be yours.’

‘Are you sure,’ she said, her eyes twinkling.

‘Of course, Kesarbai. Today is a historic day for the city and for the people of Maharashtra. And you have graced the occasion with your tremendous art.’

‘Then give me your office for one day.’

The chief minister kept his cool. ‘What will you do with it, Kesarbai? Do tell me, and I shall try and implement what you have in mind.’

Kesarbai laughed and said, ‘Never mind. But next time, don’t make promises you cannot keep!’

When Dhondutai lay down to nap, I went into the other room and stared at the portrait of the woman with the voice of a man; a woman whose temper had once prompted a wealthy Bombay businessman to crawl under the creaky wooden stage and sit in hiding for two hours so that he could listen to her music, because she had banished him from attending her concerts after they had had a tiff.

Kesarbai was known for her tempestuous outbursts in public. She would scrutinize her audience like a hawk and ensure that none of her ‘enemies’ was present. If someone made the mistake of coughing while she was singing, and she happened to be in a bad mood, she would stop in the middle of her performance and order the hapless listener to leave the auditorium.

Why was she so mean spirited, yet so gifted? So narcissistic and self-destructive? How did these base traits exist in conjunction with her sublime art? Or could it be the other way around? That to achieve that level in music, or any creative endeavour, demands an element of mania? I found, as I entered her world, that Kesarbai’s determination to become a great singer—the best in the world—was not a spiritual quest. Rather, it was driven by vengeance, and rooted in unimaginable pain.

* * *

It was 1914. A lavish feast was underway. Two wellknown Marathi families were joining in matrimony through their children Hirabai and Anantrao. The men strolled into the hall from the front entrance, greeting one another jovially. The women, as was the custom, came in from the back and stayed there, hovering around the bride, commenting on her jewellery, gossiping about the decor. As the men sat around sipping sandalwood sherbet, they were surprised to see a young woman amble in through the front gate. She must have been in her early twenties. She wore a silk sari with a sleeveless blouse. Her eyes were lined with kohl, her lips faintly stained with betel leaf. Her neck glistened with a gold necklace. There was no shawl of modesty wrapped around her shoulders which was customary among women in those days. She didn’t pay attention to any one, but was conscious of the eyes on her, some lascivious, others merely curious. She glided jauntily into the women’s enclosure. An audible murmur went around the party of men and one of them got up, strode inside and whispered something into his wife’s ear. A few minutes later, the groom’s mother called the bride’s mother aside.

‘Who is that woman?’

‘Her name is Kesar. She is one of our tenants. She lives in the building across ours.’ Hirabai’s mother did not dare reveal that the pretty young guest was quite friendly with her daughter. Or, that they would holler and squeal at each other from their windows, even if they were separated by an unbridgeable social chasm.

‘Well, clearly, she does not belong here. Women like that should not be at functions like ours. We are Brahmins. What will people say…’ hissed the mother of the groom.

‘Tai. What do you want me to do? I can’t possibly ask her to leave now that she is here. That would be deeply insulting.’

‘It would be far more inauspicious for her to stay. The ceremony is exactly half an hour away. If you still want the wedding to take place, please make sure she is not here. The choice is yours.’

The hostess hurriedly went and whispered something in the young woman’s ear. Kesar stared at the older woman in disbelief. Her kohl-lined eyes filled up but she did not allow even a drop to escape. Then, without saying a word, she got up and left.

As she walked home crying in the noonday sun, the enraged young woman swore to herself that one day, she would make this very gentry pine for her.

She did—she became the great Kesarbai Kerkar. But the stigma that surrounded ‘singing women’ was not about to disappear very quickly. It festered in the hearts of a patriarchal society, which enjoyed its women entertainers but didn’t want them mingling with their daughters.

In fact, even fifty years later, people harboured the same feelings about this community. Long after Kesarbai had established herself as a great diva, and long after India had entered an era of so-called modernity, when her granddaughter Il was getting married in the nineteen seventies, she faced similar murmurs of outrage because of her lineage. It didn’t matter that the bride’s grandmother was one of the greatest singers India had ever heard. She was, after all, a ‘bai,’ from the courtesan community.

* * *

There are numerous stories about singers like Kesarbai who, despite their artistic achievements, had to silently endure the slights and humiliations flung at them. Gohar Jaan was one of the most formidable women singers of the early nineteen hundreds. She dressed and lived like a queen. She used to wear an invaluable diamond brooch on her left shoulder, which is why she always had two rifle-wielding soldiers stand guard on either side of her while she performed. Once, in Calcutta, she had gone for a ride in a carriage led by four majestic horses. The British governor, who happened to ride past her, automatically saluted her, assuming she was royalty. He was later told that the person in the carriage was a ‘singing girl’. He was so livid that he had shown respect to a mere courtesan, that he passed an edict declaring that no one besides royalty could use a fourhorse carriage.

The fact that Gohar Jaan was the reigning queen of music in India was not pertinent to her social status, especially in the eyes of men. They may have plied her with pearls and promises in their weak moments, but at the end of the day, she was deemed a woman of disrepute. This was the paradox most women singers lived with.

Copyright © 2007 by Namita Devidayal. All rights reserved.

Excerpted from Music Room: A Memoir by Namita Devidayal

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.