| Acknowledgments | p. ix |

| Introduction | p. xi |

| From San Diego to Afghanistan Through Frankfurt, Vienna, Pakistan, and Kashmir 1993 | p. 3 |

| Afghanistan winter 1993-94 | p. 23 |

| First Trip to Chechnya 1995-96 | p. 41 |

| Youth | p. 133 |

| How the CIA Betrayed Me 1996-99 | p. 147 |

| Chechnya Revisited 1999-2000 | p. 217 |

| September 11, 2001 | p. 247 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

From San Diego to Afghanistan Through Frankfurt, Vienna, Pakistan, and Kashmir

1993

MASJIDUL NOOR WAS THE FIRST MOSQUE I ever attended. It was in the ghetto of Fiftieth Street and University Avenue in East San Diego and had formerly been an old house. Black, Asian, and Hispanic gangs roamed at all hours of the day, but the immediate area around the mosque was a bustling Islamic community of Pakistanis, Kurds, Somalis, and Afghans. When I first walked in, I thought that the other Muslims might regard me with suspicion or amusement, but no one gave me a second look. I approached one of the men there when he'd finished praying and asked him for the Imam. He told me that the Imam wasn't there yet, but that I could speak to someone in a little house next to the mosque, which is where I found Khamil.

Khamil, a young and very friendly Pakistani, took an interest in me as a new Muslim. I hung out with him until Salaatul Maghrib , the prayer made just after sunset, and then he introduced me to Ibrahim, a very large man in his forties or fifties with a big, gray beard and an intimidating demeanor. When we spoke, I found him genuinely friendly and kindhearted. The Muslims at this mosque were called Tabliqis and Ibrahim was the emir, or leader. I told him about myself, and he could see that I was sincere about Islam. When I mentioned that I didn't know where I would be living in San Diego, he suggested that I rent a room in Khamil's little house next to the mosque. This pleased me; I would be around other Muslims and have the mosque just next door.

I fell into a comfortable routine with the Tabliqis. Every morning before sunup I would awaken to one of the guys outside making the azan , or call to prayer. After prayer we would get ready to go to work, and after work we would hang out in front of the mosque.

On the weekends the Tabliqis would send out jamats , or groups of the faithful, to mosques in other cities. Sometimes we would drive up to Los Angeles and meet with fellow Muslims, and as I began to learn more about Islam, I adopted traditional Islamic dress. In a while I became a regular feature of the area-the guy with the big red beard and turban walking down the street.

After about four months I became concerned about the war in Bosnia, where the Serbs were slaughtering Muslims by the tens of thousands. Not only had the United States refused to help the Bosnians, but we had placed an arms embargo on them as well. Perhaps the most disturbing fact was that the more I learned about the situation, the less it seemed the Muslims around me cared about it. No one in the mosques talked about the war, and when I asked questions they seemed unconcerned.

Finally I went to Ibrahim, the emir, and told him that although I was new to Islam, I'd learned a great deal in the past four months and felt that I was ready to defend our religion. To my surprise, he didn't understand what I was saying, so I told him that I wanted to go to Bosnia for jihad. His response was even more surprising. He told me that because the majority of the Muslims in the world weren't practicing the religion properly, there was no jihad at the present time. I couldn't believe what I was hearing. This sounded like a copout to me. Jihad is an established principle of Islam, and when Muslims are being attacked and killed, it is the duty of every adult male Muslim to go to their aid. Yet Ibrahim was telling me that since most Muslims didn't practice Islam properly, I shouldn't concern myself with whether they lived or died.

Later I discovered that the Tabliq was basically a pacifist movement that had originated in Pakistan. Many people, myself included, believe that the movement had actually been started by colonial Britain to pacify the Pakistanis. Britain's imperial dreams would have turned to nightmares if the Islamic scholars had declared a jihad, so the British had fostered a movement within Islam that didn't include jihad.

Although I continued to stay around the Tabliqis, I became very disillusioned. One night, while sitting in front of the mosque, I met a man named Abdullah. Originally from Panama, he'd fought the Soviets in Afghanistan and the Serbs in Bosnia. I was drawn to him immediately, and asked him whether someone could get into Bosnia. He told me that a friend of his had just left for Bosnia, but that he would be back in a month and might be able to help.

I saw Abdullah at the mosque about a month later; he told me that his friend had just returned from Bosnia. The next night a man asked for me at the mosque. His name was Muhammad Zaky, and he was a large older man with a tough-looking face and a long red beard; during our conversation I learned that he'd been born in the United States of Egyptian parents. When he asked if I wanted to go to Bosnia, I leapt at the chance. He said it wouldn't be a problem, although it would take him a couple of weeks to make arrangements.

This was exhilarating: not only would I be able to help the Muslims of Bosnia but I would also complete my own faith. Jihad is the highest act of faith in Islam. The prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, said that if a Muslim dies without making jihad, or at least having had the intentions to make it, then he dies with a form of hypocrisy in his heart.

I spent a lot of time with Muhammad Zaky as he made the arrangements for my trip to Bosnia. He was very intelligent and had spent many years fighting jihad. Like Abdullah, he had fought first in Afghanistan against the Soviets and then in Bosnia against the Serbs. Although he never spoke about it, some said that he had testified before the House of Representatives about the mujahideen in Afghanistan, and that his testimony had been instrumental in ensuring that the United States sent Stinger antiaircraft missiles to the mujahideen. Muhammad Zaky had a wife, two teenage daughters, and a son named Umar, a bright kid of about eleven or twelve who wanted to go to jihad like his father. As I became acquainted with Muhammad and his family, I never imagined that I'd end up bringing Muhammad's final words back to his son, after he'd died in a place I'd never heard of yet, called Chechnya.

Muhammad lived a simple life in San Diego when he wasn't fighting on the battlefields of faraway lands. He had a window-tinting business to pay the bills and ran the Islamic Information Center of the Americas out of an office in downtown La Jolla. I spent most of my time with him there, surrounded by piles of Islamic literature and shelves filled with videocassettes about the jihad in Afghanistan and Bosnia that were stacked all the way to the ceiling. We spent hours watching combat footage of the war against the Soviets.

The night before I left, Muhammad and the guys in his weekly jihad class threw a small going-away party for me. We sat together and drank tea and ate Arabic sweets. It was a joyous occasion, and at the end everyone hugged me and wished me well. Then Muhammad Zaky and I returned to his apartment, where we stayed up most of the night going over our plan. I'd fly to Frankfurt, where an Arab would pick me up, give me some papers, and put me on a train to Vienna. Once I reached Vienna, other contacts would transport me to Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. I would present myself as a journalist at the United Nations headquarters in Zagreb and obtain an unprofor pass, or official U.N. pass. Until recently, the route into Bosnia had been wide open for mujahideen from all over the world, but conditions had changed, and by the time I was ready to go entrance was nearly impossible. One of the few points of entry was the U.N. flight into Sarajevo, and to get on that flight I would need an unprofor card.

Muhammad Zaky took me to Lindbergh Field to catch my flight to Frankfurt. As I boarded the plane I looked back and saw him smiling at me. But when I arrived in Frankfurt and cleared customs, nobody was waiting for me. I tried calling the Arab man, but I wasn't able to get through. I wasn't able to reach Muhammad Zaky either, so I made my own plan. I traveled to Vienna by train and tried to call my contacts there; again, I couldn't reach anyone. However, I did have an address for my contacts' mosque, so I took a cab there.

Once I found my contacts at the mosque, everything went more smoothly. I stayed with them in Vienna for almost a week. I was supposed to take another train from Vienna to Zagreb, but just before I was to leave one of the guys found three Arabs from a relief organization who were driving to Zagreb, so I caught a ride with them. The customs agents at the Croatian border gave one of the Arabs a hard time, but eventually we were able to get through. We arrived in Zagreb early in the morning, and the Arabs dropped me off at an office, where I met two of Muhammad Zaky's contacts.

Both were from the Sudan. They were running a relief organization for the Bosnians. They had no problems with letting a fighter sleep in their office, but they wouldn't have anything to do with getting me into Bosnia. I rested for a day and then went down to the U.N. headquarters for my UNPROFOR card. One of Muhammad Zaky's friends had given me a forged letter saying that I was a reporter for the "La Jolla Tribune ," but when I sat down in front of the U.N. official to get the pass, he nearly laughed at me. I must have made a humorous figure-some dumb nineteen-year-old kid with a big red beard and a shaved head claiming to be a reporter with nothing more than a forged letter to back him up. The official gave me a list of items I needed to prove I was a reporter, which included three sample articles. Needless to say, I walked out of the office feeling stupid.

I went back to the Sudanese and told them what had happened. They said that another organization in Zagreb needed someone who spoke English. This organization also had one of the last land routes into Sarajevo, and when I went to its office the director offered me a job. But I was naive and looked at everything in terms of black and white. I told him that I'd left America only to fight in Bosnia and asked if the organization would give me a ride on one of its convoys that was scheduled to leave soon. The director told me that this was impossible; they would have nothing to do with helping mujahideen enter Bosnia.

It's interesting to note that at this writing, these same organizations, which wouldn't help a single fighter enter Bosnia, are being shut down by the U.S. authorities for supposedly aiding terrorists. Most mujahideen would view these organizations as disgraceful because they refuse to aid the jihad in any way. Despite this, they are being shut down by the FBI.

None of my plans were working out, so I called Muhammad Zaky. He told me to go back to Vienna and wait for him there; he would be arriving in a couple of weeks. Back in Vienna, however, I became more and more frustrated and impatient with the situation. In retrospect, I know that waiting somewhere for a couple of weeks is nothing, but at the time it seemed impossible. A couple of days after I'd retreated to Vienna, an African-American Muslim named Laith came to the mosque. We started to talk, and he told me that if I wanted to make jihad, he could put me in touch with some of his friends in Pakistan, who in turn could get me into Kashmir. My primary goal was to help Bosnia, but I was too impatient to wait, so against Muhammad Zaky's advice I took off for the Pakistani city of Karachi.

The customs officials at Karachi International Airport must have thought I was joking when I asked, "What visa?" It was the first time I'd been outside America, and I'd never heard of a visa. But I was wearing the traditional clothes of the Tabliq and I told them I'd come to Pakistan for carouge , a pilgrimage that Tabliqis make, so they relented and gave me a seventy-two-hour visa. To my surprise, somebody was actually waiting for me when I left the airport. He drove me to the office of Harakat-ul Jihad, a Pakistani jihad group. The next day the group took me to one of the Tabliq schools in Karachi to meet one of the emirs. Although the Tabliqis are opposed to jihad, the emir agreed to give me a letter to take to the Pakistani immigration officials for an extension on my visa, and as a result I was able to stay for three more months.

I was supposed to leave Karachi the next day, but the night before my flight to Islamabad I awoke with incredible pain, fever, and uncontrollable shaking. By morning I was almost delirious with pain, and my head felt as if it was going to explode. Every ten minutes or so I stumbled to the bathroom for an exhausting bout of diarrhea. The Harakat-ul Jihad office didn't know what to do; after much discussion I managed to persuade them to take me to the hospital, where the doctors wouldn't touch me until I'd paid them. Three days and an IV later, the doctors told me that I had a bad case of dysentery and instructed me to return to the States. As soon as I was strong enough to walk, I took the flight to Islamabad.

As usual, no one was waiting for me at the airport. It was late at night and all I had was the address for the Harakat-ul Jihad office, so I hailed a taxi. The driver had to stop three times to ask directions for sector I9-4, and when we finally found sector I9-4, he couldn't find the house. He stopped and asked a passerby, who also didn't seem to know the location of Harakat-ul Jihad. When the man looked into the back of the taxi and saw my my big red beard, his eyes lit up.

"Are you a mujahid?" he asked.

At first I didn't know what to tell him, but I thought, What the hell, I'll take the risk. "Yes?" I replied hesitantly.

"O- kay ," he said. He pointed to a large three-story house at the end of the street. "That one. That is the house of the mujahideen." Apparently what went on there wasn't a big secret.

Continue...

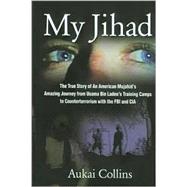

Excerpted from My Jihad by Aukai Collins Copyright © 2002 by Aukai Collins

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.