Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

I started skating at nearly the same time I took my first steps. Mother taught me how on the outdoor rink at the local park. Every weekend she took me there and we skated in circles the wobbly gait of the swamp-skater, pushing off with the serrated tip. The spring after I turned fifteen, the ice melted as it did every April, and still I showed up, like clockwork, my skates slung over my shoulder. I watched the ice dissolve back into Allen's Creek. Mother drove down and met me, popped open the passenger-side door of the family camper-van, and said, "Hop in. I've got a surprise for you." That day I skated on an indoor rink for the first time. There was something in the long mile of that white room, in the coolness of the air and the smell of the ice -- like the inside of a tin cup -- and all the while outside I knew the sun was tapping on the roof, warming the tiles, begging to be let in. I was hooked. I joined the rink's figure skating academy.

The girls at the Rochester Skating Academy in 1984 were a hardy bunch -- great jumpers, who raced around the rink backwards at high speeds. I was the one in the corner by the sidewall pushing my wire-rim glasses up my nose, my stockings bunched at the knees. I did not jump. My spins were slow and careful. But I did have one thing going for me. I was good at Patch.

Patch was named for the sectioning of the ice into six-by-eight-foot strips or patches. The first thing to do when you get to your assigned patch is carve two adjacent circles, using an instrument called a scribe (which looks like an overgrown compass). On that huge number eight you try to skate the perfect figure. It's harder than it looks -- keeping the cut line of the blade arced, the skate moving at a good clip, never straying from the two circles. It was my favorite part of the day: the collective silence of concentration, drilling over and over a single blade turn, the subtle weight shifts, from front to back, right to left. This measured intricacy, the repetitive devotion it required -- it was the closest you could get to praying on ice.

In late July, three months after I started my indoor skating career, I had an accident during morning Patch Hour. While practicing the 180-degree turn in the center of the eight, I slipped and fell. Sixteen pairs of eyes looked up from their patches and stared at me. I tried to stand up. My leg warmers slid down over my heels. I moved to adjust them, and then I saw it. In the center of the eight, at the fulcrum of the north and south circles, lay a spot of blood. A darkening stain ran across the crotch of my skating dress. I crossed my legs.

Moments later, in the bathroom at the Rochester Skating Rink, dark flowers of blood spread across the toilet water. I called Mother from a pay phone in the hall.

"It's your first," she whispered into the phone. She was at the architecture firm where she worked as a secretary.

"I've got blood all over me!"

"All right. I'll meet you in the bathroom, the one by the soda machine."

"Bring a bucket."

"Oh stop," she said. "It's not that bad."

I waited for Mother in the stall farthest from the door. When she entered, her low heels clip-clopped across the floor. She went straight for the last stall and opened the door. My skates were still on, the laces loosened. I had crammed half a roll of toilet paper between my legs. She slouched, one hand on her hip. "Alroy," she whispered as she shook her head. It's not my name. It's ours, my brother's and mine. A pet name she made up, combining Roy's name and mine into a single shorthand. "That bad, Alroy?" she asked.

I nodded and gazed up at her.

My mother stood in her homemade wraparound skirt with the blue flowers. She had tucked a white summer blouse into its ribboned waist. She wore her hair short, in a Dorothy Hamill cut, and in the humidity it curled out around her ears like wings. She slid her purse off her shoulder, pulled out a pack of extrathick sanitary pads, a bottle of pills, and a collapsible camping cup. She crossed over to the sink, filled the cup with water, and thrust both her hands under my nose. One held the cup, the other two pink pills.

"Take these."

I swallowed the pills. She ran her hand over my forehead. I pushed her away. She handed me a pad and backed up. Through the metal door I heard her sigh. She tapped her foot. I leaned back. The flusher jabbed me in the kidneys. I peeled the white adhesive strip off the back of the pad and slid my skating dress down.

Mother drove me home. After she set me up in bed with a bottle of Midol and a copy of the Psalms, she made no proud speech about my initiation into womanhood, offered no advice on the prevention of menstrual cramps or the application of sanitary pads. She cleared her throat, ran her fingers through her hair, and said, "I'll tell Daddy. You tell Roy."

And with that she left me and returned to work.

When Roy showed up outside my bedroom door later that afternoon, he was holding a portable radio. He had just come from his morning job as a groundskeeper at a local country club and was already dressed for his second summer job as a cashier at Tops Supermarket. The stiff red uniform vest, boxy and oversized, hung on his narrow frame. Wrapping a leg around the door, he leaned into the room. "Hey, little sister, who's your superman? Hey, little sister, who's the one you want?" he crooned along with Billy Idol. Then he pulled back, hit his head against the doorframe, and tumbled to the ground, moaning in mock pain.

"Roy-dee,"I hollered, from under the covers.

"LittleSister,"he hollered back, pulling himself up.

Billy Idol was not his music of choice. He was more a fan of the Police and the Who, but he knew this song drove me crazy. Whenever the local station played it, he rushed toward me, his arms out, singing at the top of his lungs.

I yelled over the sound of the radio. "I'm sick!"

"What?" he yelled back.

I pointed at the radio. He turned it down.

"I'm sick."

He walked into the room. "How do I look?" Under the uniform vest he wore an orange Hawaiian shirt and maroon running pants.

"Terrible. Everything clashes."

"Good!" His head bobbed up and down. "It's your turn to do the dishes."

"Will you do them?"

He glanced over at me. "What's wrong with you?"

"Nothing."

His hands thrummed out a beat against the door. "I thought you said you were sick."

I could feel the blood rushing to my head. My face grew hot. "I have my period."

"Your what?"

"Myperiod!"

The thrumming stopped. I could hear him breathing; his lungs were congested. "Oh," he said.

He became engrossed in the pattern of his Hawaiian shirt. His hair was long; he had let it grow now that he was not in school. It ran over his ears and scrolled out around the base of his skull. The sun was shining in the window over the porch, and the evergreens' bright needles shimmered in the windless afternoon. He stepped into the room, picked up my skates, and started swinging them by the laces.

"Don't touch those," I said. I reached across the bed, grabbed them from him, and shoved them under the blankets.

He cleared his throat. "It's supposed to rain tonight," he said.

"What do you want, Alroy?"

"It's your turn to do the dishes."

"You do them."

"No, you."

"No, you."

"No, you."

"Loser," I said.

"Dweeb."

"Mutant."

"Moron!" And then he lost it. He broke into a grin. Paper white teeth, three dimples -- one on either side and a little dent in his chin.

"Alroy," I said.

He disappeared behind the door again. He coughed once. The breath rattled in and out of him. He had just recovered from a nasty bout of bronchitis. One hand on the door, the other on the doorframe, he leaned back into the room and smiled. From my position on the bed I saw only half of him. A slice of brown hair, tan skin, and the hideous orange and red.

Outside a mourning dove cooed. The sun beat down on us through the back window, no trace of the coming storm. It was four in the afternoon. I looked away. I felt a slip in the air, a nearly imperceptible change in temperature. I turned to catch him, but he had already left.

I fell asleep, my hands wrapped around my skates. I slept straight through without eating supper, without going to my evening job at the Sisters of Mercy Convent. And as I slept a storm gathered over Lake Ontario, ten miles to the north. At one o'clock the sky broke open. Rain pelted the ground, rivered into the gullies along Penfield Road. It rained all night, and it was raining the next morning when Roy left for work. Friday, July 27, 1984. Father stopped him at the front door.

"What are you going to do," Father asked, "in the rain?"

Roy tossed the keys to the van from his right hand to his left and hitched up his shorts. "We'll wash the golf carts," he said.

At 5:51 A.M. Father opened the front door for him. Roy ducked into the driving storm. He was gone. It was not for another two hours, when it was too late, that I would walk into the kitchen and see. He had done the dishes after all.

Copyright © 2004 by Alison Smith

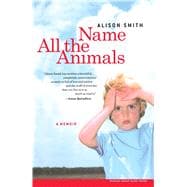

Excerpted from Name All the Animals: A Memoir by Alison Smith

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.