The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

The Existential housewife

Lisa D. Williamson

Melinda sat on the dusty attic floor, her jean-clad legs tucked beneath her. She read the dictionary quotation one last time and closed the notebook, a relic from college days. Stroking the burgundy faux-leather cover with the barest touch of her fingertips, Mel hugged the book to her chest.

The one window in this section of the attic was covered securely with opaque plastic sheeting, allowing only a diffused yellow light to filter through. Melinda stared toward the small window, not really noticing it or the swirl of dust motes caught dancing in the dim illumination. She had long since stopped sneezing; the greater part of the filth she had disturbed when she had first come up had subsided again, settling over her like a veil, sifting into her hair, smudging her cheek, leaving streaks on her jeans. The unfinished floorboards and the rough-hewn rafters that met in a severely cramped, inverted V made the attic appear rustic, not at all like the immaculate, elegant house beneath. It was, instead, the untidy graveyard of buried memories and past lives. There were precarious stacks of cardboard and plastic storage boxes piled up to the insulation-blanketed beams, holding clothes that were no longer in style and had years ago ceased to fit, books that no one had read in more than ten years, broken tables and lamps that still waited patiently to be fixed--all the detritus of lives lived too long in one spot. The notebook Melinda now held was taken from a box crammed into the back corner, an old, dilapidated cardboard storage crate that contained her college work from long ago: her term papers, her creative writing assignments, her class notes.

Melinda didn't know what obscure impulse had drawn her up here. The attic was a place where no one ever came, except to deposit another box of unwanted junk. She ran a dusty hand through her wavy brown hair. She would have to get moving soon. Although the house was ready, she was not. She still had to shower and shave her legs. She still had to dry and pull and spray her unruly hair into some semblance of casual chic. She still had to stand in front of her open closet and decide what she liked, what would fit, what would be impressive to the people Bailey had invited over to impress. It was an effortless type of evening; God knew she had done it often enough before. But for some reason, it seemed hard today. The thought of standing for one more night, gazing with incredulous admiration at some fool half her height and a third her intelligence, brought the same strange mist to her eyes that had been appearing unbidden all day. If she didn't move soon, and move quickly, she would not be ready by the time Bailey came home. Bailey would be annoyed.

But somehow, even that thought was not enough to propel her to her feet and back down to her life.

Melinda again opened the old notebook, opened it to the page still marked by her finger. Words seemed to jump out at her, hitting her with the impact of a slap to the face. Isolated. Hostile. Indifferent . How true.

Was she suffering a midlife crisis? Bailey would be angry that it came on the night of his most important party. He hated whiners. Why her? Why now? It was all very inconvenient, a feeling she neither wanted nor could do anything about.

Melinda bent her head over the open notebook, inhaling the fusty scent of old paper, as if by immersing herself in the smell of school and independent thought and the still-new promise of things to come, she could make herself forget that twenty years had passed, and that she had grown middle-aged and fat and gray and boring like all those dull people she had vowed never to be like.

What had happened? Was it that her kids were close to leaving home and leading their own lives? She barely saw them anymore--now that Bailey had gotten Jamie and Stephen their own car so they wouldn't be borrowing hers all the time, she didn't even get their urgent calls from school: "Mom, I forgot my lacrosse stick," or "Mom, if you don't bring in a note, I won't be able to go on the class trip." Her children had turned into itinerant boarders who never seemed to need her anymore. Was it just a preview of empty-nest syndrome? Was that it?

Or was it Bailey? Was it that he seemed to resent her staying home, when for twenty years, it had been her job? Was it that he looked at her now as if she were just some extra mouth to feed, someone who wasn't pulling her own weight? Perhaps he thought that after twenty years she could just slip into a high-paying executive job, when the only entry on her resume was "Wife and Mom."

The indifference from her kids, the hostility from her husband--it all added up to Melinda's sense of isolation. She rose abruptly, tossing the notebook back into its box.

"I'm an existential housewife," she said aloud and, with a soft noise that could have been a laugh, went downstairs to change. The change first happened when Melinda was getting ready for the party. She had stayed a long time in the shower, letting water almost hotter than she could bear beat on her, washing out both the dirt from the attic and, she hoped, the strange feeling of melancholy. Perhaps, she thought, the perfumed soaps and conditioners and lotions would mask the rancid taste of despondency she could neither explain nor shake.

Melinda stood naked, steamy and still red from the shower, feeling the nubby texture of the bathroom mat underfoot. Although with the modern ventilation system in the bathroom, the large and well-lit mirror was steam-free, it had become her habit in the last few years to perform her ablutions without looking at herself, at the old stretch marks, the drooping breasts, the rounded stomach. Mel picked up a plastic bottle of styling gel from the patterned blue, red and yellow handmade Italian tiles that covered the sink shelf and poured a small amount into her hand. She had performed this beauty ritual hundreds, perhaps thousands of times in the past, and was comforted by the thought that following this routine would allow her to slip back into her normal frame of mind. Slap some gel in her hair, rub it through and tame her mane into something elegant. Click your heels together three times and you'll be home .

But this time routine did not save her. She poured the gel into a small circle on her hand and casually looked down. Mel blinked and her breath caught in her throat with a strangled gasp. She shook her head violently and looked again. Her heart faltered. Melinda could not tell where the gel ended and her hands began. Even as she again blinked hard to clear her vision, wondering what was wrong with her, the fingers on her left hand turned translucent and gooey, like the gel, and began drooping toward the floor, as if they were made of the same viscous liquid and were going to drip off her arm.

Mel cried out and leapt sideways, as if to escape her own body. In her terror, her hand flailed over the counter, sweeping bottles and jars to the floor in a horrific crash. She pressed her right hand to her face in an automatic reflex of panic, then jerked it away again in equal hysteria. She could not tell, in that moment, if she had felt firm flesh or not. Her thoughts were a jumble, a sane and calm "Thank God no one's home" punctuated by a darker, insistent "Oh my God, oh my God," overlying a deep, thudding dread that was echoed by the pounding of her heart. Mel stumbled backward, hitting the toilet with the back of her legs, collapsing onto the commode. She had her eyes squeezed tightly shut, afraid to look at her hands. Afraid not to. Unable to prolong the moment further, she opened her eyes slowly--just a slit--her forehead knit into rows of horror. Her two hands were spread open, palm edge to palm edge, as if to receive communion, the small quarter-size blob of lotion sitting intact on her perfectly normal left palm. Melinda stared at her hands in disbelief, and began to shake uncontrollably.

As Melinda saw it, when Bailey found her sitting, still naked, shivering on the commode countless minutes later, there were a couple of possible scenarios, neither of which was very comforting. Either her eyes were going, another reminder that she had passed the forty-year-old borderline and was in the wasteland of failing organs, or she was going mad, whether because of midlife crisis or empty-nest syndrome or pre-menopause, it hardly mattered.

And yet ... Mel kept playing back the scene in the bathroom in her mind. Much as she would have liked to persuade herself it had never happened, as much as she knew delusions were real to the delusional, she couldn't shake her gut feeling that something had happened. She inspected her hands for the hundredth time since the incident. They were well-cared-for, manicured hands. Nothing outré . An appointment with the doctor, she thought, rising abruptly and moving toward her bedroom to stand in front of the closet. An eye exam. Then maybe Prozac, or Valium. That should help.

And when Bailey, from across the vast, Waverly-decorated room, asked if anything were the matter, while pointedly tapping on his watch, she calmly told him, "No, I'm fine. I'll be ready soon." And he accepted that, ignoring the state he had found her in, confident, as always, in her ability to make things right.

"Melinda, I don't know how you do it." Melinda stared down at the three strands of hair trying to pretend they were a hundred stretching across the top of Bob's head as he crammed another miniature quiche into his mouth. They stood in her elegant living room, surrounded by all the other guests, ankle deep in wall-to-wall, overlaid with an intricate oriental. "My wife doesn't even know where the kitchen is. But I bet she could tell you how to get to the tennis courts fast enough."

Bob laughed. Melinda moved a corner of her mouth up in a tepid imitation of a smile. She had spent the evening avoiding looking at her hands, and instead looked at the blob of cream cheese dough adhering to Bob's chin and at his shirt straining to cover his executive paunch. Melinda resisted the impulse to pat Bob's stomach, much like she would have touched a pregnant woman's, feeling for the kick.

"Well at least someone in the house knows where the kitchen is," she thought as she moved through the party noises of animated conversation and tinkling ice on glass to offer hors d'oeuvres to her other guests. But she didn't say it; she had long ago excised such acerbic comments from her conversation.

What had happened to her? In her youth, she would have skewered Bob, and the dozens more like him in the room, with barely a thought. She had been militant, freethinking and outspoken. Mel could precisely trace her path from the college-day Melinda to the present-day matron, and she could not put her finger on exactly where things had changed. She had learned, slowly, step by step, that life was a compromise. That if she wanted to get to point C, she had to pass through point B. The fact that she now--at this late point in her life--found point C inadequate completely confused her.

She hadn't particularly wanted to get married. But she was madly, passionately in love with Bailey, who was strong, ambitious and full of his own vision of the future. Mel had thought it fantastic that two people with such radically different views of the world could come together, almost an affirmation of the vision of world peace that had been sweeping the nation's campuses back in the sixties and seventies. What did it matter to her, a little scrap of paper that said they were married? She would have him, paper or not. Although he was equally passionate about Mel, he would have her only with the paper. So, right out of college, they got married. It was a compromise, but in Mel's view, not a big one: She was monogamous by nature and, married or living in sin, would have stuck to Bailey till the end of her days anyway.

Mel had been working in a publishing house when she got pregnant, more than a year later. Her job was strictly grunt work, reading unsolicited manuscripts that were mostly boring tripe. The pay was dreadful, but both the job and the salary were the requisite dues that would enable her to move higher up the ladder. Bailey was floundering around for a purpose. He had tried repping, then sales, and at the time of Mel's pregnancy, had just started at a brokerage house. As with Mel's job, the hours were horrific and the pay was pitiful. Mel and Bailey discussed their goals for the baby endlessly. They both agreed that they didn't want to have their baby just to shove it into daycare. They both agreed that Bailey's potential for a high salary was greater than Mel's. They both agreed that Mel could get freelance jobs from her editors and work out of their small one-bedroom apartment.

So Mel became a housewife. It was a choice she had been comfortable with. When she saw the strain on the families where both parents worked, when she saw the illnesses daycare children came home with, when she saw the children who grew up brash and cocky because of their proximity to older children at the daycare, she knew she had made a good compromise. It was only when she was dismissed after the dreaded "Do you work?" question that she felt deficient. But really, what could be more important than successfully launching her own contribution to the next generation? Mel still couldn't answer that question. Even when she found out that not having more than two consecutive hours of sleep a night prevented her from being able to accept freelance jobs; even when washing diapers, making baby food, doing all the millions of little, insignificant things that she felt it necessary to do first for Jamie, then for Stephen, took up every waking hour; even then Melinda couldn't say what she would have done differently.

"Mel!" Bailey called her from the door of the kitchen, breaking into her reverie. It was that neutral-sounding voice an angry spouse uses in front of other people. She let her guests take the tray of food from her and wove her way over to him. She stood before him and raised an eyebrow in question.

He grabbed her arm--not so it hurt, but so that he had her full attention.

"Mel, you knew Frank Haldeman was coming tonight. You know he likes his martinis with three olives. Where the hell are the olives?" He waved a naked martini in front of her face, slopping the liquid from side to side in the wedge-shaped glass.

Mel looked at him and thought, I can't look at my hands because I'm afraid of what I'll see, and you're worried about Frank Haldeman's olives ?

Instead of saying this, though, she calmly took the glass from him, said, "I'll check," and went to the refrigerator. But she knew there'd be nothing there. She'd been in the attic all afternoon and had completely forgotten the olives. She bent over and looked into the well-stocked fridge anyway.

"I knew Mellie would fix me up." A loud and cheery voice attacked her from behind. She turned. Frank Haldeman crowded up to her, virtually pushing her into the refrigerator, and gave her a kiss on the cheek. "I told that husband of yours, Mellie, that you always take care of me."

Mel hated Frank. She hated the power he exuded, she hated the easy familiarity he assumed with her, she hated that he called her "Mellie," a perfectly revolting name that she somehow suspected he knew and used for that reason. But Bailey needed Frank--Bailey damn near worshipped Frank--so Mel always kept a lid on her true feelings. She thought, though, as with her name, Frank knew what was unsaid and reveled in the power it gave him.

But now she had no idea what he was talking about. Was it a joke? Was he just underscoring that Mel had indeed not taken care of him? Melinda looked down. The glass she was holding was a piece of Waterford she had picked out when she and, Bailey had gone to Ireland. She had always loved the way the hand-cut facets sparkled in the light. Frank's martini looked like a transparent oil slick in the elegant glass. And there, impossibly, nestled in the bottom, refracted through the liquor, were three perfect green olives, impaled on a toothpick. Mel sucked in her breath and looked up in panic at Frank's face. What the hell was going on? Where had the olives come from? Frank didn't notice Mel's reaction. He plucked the glass from her hand and moved on to his next contact. As he pulled the martini from her, Mel watched her fingers in horror. She only had three. The fourth gradually, almost imperceptibly, transformed from three green spheres run through with a toothpick to a two-jointed finger topped with a perfect mauve, manicured nail.

Mel thought, It's not enough that a few hours ago my fingers were dripping off my hand. Now they're beginning to turn into condiments. Mel watched, bereft of speech, as Frank retreated from her, waving his now unadorned martini around, greeting friends, enjoying himself, oblivious to what had just happened.

"Sorry, hon," whispered an equally ignorant Bailey in Mel's ear as she stood frozen, looking at her hand. "I panicked. How could I ever doubt you?" He kissed her lightly and moved off himself, to trawl the party.

Mel fled to the powder room. She did not turn on the light, and stood in the room lit only by a small scented candle at the sink, looking at herself in the mirror. She knew now she wasn't losing her mind--Bailey and Frank had seen the olives as clearly as she had. No one had yet noticed that she was morphing, but surely that was only a matter of time. How would her family react? What would they do when they found out she was dissolving away?

Mel looked hard at herself. Slowly, she picked up the small glass bowl with the lit votive candle from the vanity. Concentrating, Mel held her hand over the flame. She could see a thumb and four distinct fingers, the bone structure, the faint glow of the translucent veins and cartilage and flesh. Everything normal. But still, something had changed.

She thought back to her original theory, that she was either losing her sight or her grip on reality. That one way or another, this was all in her mind. But now she knew that was not true, not unless Frank and Bailey were sharing her own, personal delusion. Now a third alternative occurred to her, one that was patently bizarre, although no more so than her day so far.

Melinda had spent a lifetime blending in, being invisible, a barely discernible support to her family that her body was now emulating. She was ceasing to exist as her own entity and, as she had for most of her adult life, was taking on the character and shading of those around her. Only now it wasn't just the important executives or the needy children she was reflecting. It was everyday things, things of no importance, things all about her.

Melinda found this thought almost laughable. Almost. Maybe the fact that she would entertain it at all was a sign that the second choice--she was losing her mind--was the real answer to her dilemma. But that wouldn't explain Frank and Bailey.

Mel had no idea what to do next. She had an obscure desire to run to the attic and huddle in the darkest corner until everything went back to the way it had been. But the party was going to go on, whether she wanted it to or not. Her absence would be noticed. Bailey would miss her. She would just have to go out and keep pretending nothing was happening.

A soft knock came at the door. Mel started, then said, "I'll be right out," and washed her hands in stingingly cold water as if that might keep them from changing again. She turned the light on so no one would realize she'd been locked in the bathroom in the near dark, and left.

The rest of the party took on a surreal aspect. Melinda found, as she drank another glass of chardonnay, that if she looked at things in a slightly skewed way, she might actually be able to enjoy her predicament, considering she had no control over it.

A brief moment of lightness came when Bailey approached her saying, "Frank's lost his olives, and I can't find any more."

Mel found herself answering, "If he didn't swill down so much gin, he probably wouldn't have that problem." It was a touch, a faint shadow of her former self, and although Bailey backed off in consternation, she finally found something that night to smile about.

After that small surge of self-assertiveness, Mel's episodes increased in frequency. Or maybe it was her drinking. She had tossed back a couple of glasses of wine in quick succession after she had emerged from the powder room. The alcohol had hit her empty stomach and shot through her veins, allowing her a small measure of detachment. The wine had also detached Mel from her judgment. People that just yesterday she had merely found mildly offensive or somewhat annoying, she suddenly found completely intolerable. While one small part of her brain--the last of her sobriety, perhaps--was aghast at her disloyalty to Bailey, the suddenly expansive, drunken part of her rejoiced.

No more compromises , Mel thought.

Carol Wordsworth was the epitome of the corporate wife. It was amazing, Mel had often thought, how such a small package--five feet, three inches and oh-so-slender--could be crammed with so much hypocrisy, self-absorption and downright meanness. But, as with most of the people in her house this evening, Mel was always meticulously polite to Carol, for Bailey's sake.

Carol was not only petite (Melinda's private nickname for her was "The Stump"), not only slender, but her complexion was flawless and her clothes were from the best shops. Her children went to private schools, and she drove a small white Mercedes convertible. It had always irked Melinda that someone with the personality of a pit viper could slither through life untouched by reality.

Melinda vividly remembered the day she had met Carol. It was years ago, at one of those many women's functions she attended--sports, church, school; she couldn't recall now. A mutual friend had introduced them. Carol was identified as the woman down the road who'd moved into the old Bolger mansion. Mel had been presented as the local bohemian--she made her own baby food, sewed her own home furnishings and wrote stories for her children. Eccentric, but harmless.

Carol had somehow managed to look down at the taller Melinda, had stretched close to Mel so that they were almost nose-to-nose, and had said, "I hate people like that."

Now, at the party, Mel greeted Carol, ready to do her hostess duty, ready to ask how she was, what her children were up to--the usual questions. Carol, dressed to kill in a size one cerise silk dress, was effusive: how nice of you to invite me, how pretty your house is, all the correct things to say that Mel knew she didn't mean in the least. As the two of them walked from the front door in to the party, Carol sneezed a couple of times, small, high chirps.

"Oh, excuse me," Carol held a hand to her chest. Her voice raised almost imperceptibly. "I have a terrible dust allergy." And she looked around the room, as if she could just see the particles of grime and dirt suspended in the air. As if Mel hadn't spent the last week cleaning and scouring the house in preparation for this party. As if Mel wouldn't care, or wouldn't understand, that she had just been subtly insulted. As if the other guests surrounding them hadn't heard her loud observation.

Mel could feel her face freeze into a polite smile. Ignoring Carol's remark, she laid a hand on her shoulder and gently urged her forward. "There are some people here I'd like you to meet," Mel said to Carol, thinking she'd dump Carol on Bob and his group.

Bob was predictably taken with Carol. He playfully kissed her hand when Mel introduced them. Carol kept sneezing-- chirp, chirp, chirp --then waving her hand around vaguely. "It's the dust."

Mel's hand still rested on Carol's shoulder. She wanted to dig her fingers into Carol's flesh. Instead, she watched, curiously without panic now, as her fingers slowly morphed once again. Only this time her fingers didn't melt into hair gel or olives. On Carol's bright, cherry-red silk dress appeared a long greenish-yellow trail of phlegm. While Carol sneezed, Bob's eyes flickered from her face to her shoulder, and back. Bob's friends' eyes did likewise. It was almost, Mel thought, like observing an audience watch a tennis match, the way all of their heads darted back and forth. She could see that some of them were wondering how to tell Carol about the offensive stain, and that the others had decided they weren't going to.

Bob suddenly sniffed the air. "I think I smell some more of your quiches, Mel," he said, as he and his entourage left in a mass retreat.

Mel gave one last pat to Carol's shoulder, as her fingers shimmered and re-formed into firm flesh.

"I should go help them," Mel said. Carol sneezed again, looking puzzled that her previously appreciative audience had suddenly left.

Maynard Johnson had always irked Melinda. He was a forceful right-to-lifer, a holier-than-thou neoconservative. Mel had many friends who held some of the same beliefs in varying degrees, but what irked her about Maynard was his absolute conviction that he and God conferred daily. Perhaps, Mel thought tonight, he thinks he is God. She sat in the same conversational circle as Maynard, sipping from her wine, listening to Maynard hold forth in his rational, even tones and gritted her teeth. Maynard had gotten so wound up during the evening, he had at some point thrown off his jacket, loosened his tie and rolled up his sleeves. While he gesticulated with his left hand, his right was wrapped around his scotch and water, resting on the end table that separated him from Mel. Without really thinking about it, Mel gently rested her hand on his forearm. He started, interrupting himself for a moment, then when he saw it was only Mel, went on with his story. Mel watched, as if from a distance, as her fingers again morphed and blended and disappeared. A stark blue tattoo appeared on Maynard's forearm. One of the people around Maynard, listening intently to his political talk, noticed the tattoo and shot a startled glance at him, her face suddenly stone cold. After a few moments, she whispered something to her husband, who looked at Maynard's arm and was equally stricken. Melinda watched in silence as the domino effect took place all around Maynard. Since he was used to holding the floor, he didn't realize no one else was talking until one by one, everybody had turned away and gone. Melinda was the only one left. Maynard leaned over to her and asked, "What was that all about?" Melinda slid her hand off Maynard's arm, patted him lightly and said, "Who knows? They probably just needed refills." Mel watched her fingers revert back from the blue-black swastika and went off to get another refill herself.

Sometime during the evening, the doorbell rang. Mel wouldn't have heard it above the din of the party, which was getting louder as the liquor supply was dwindling, but she happened to be passing through the foyer at the time. Opening the front door, she found Jamie's girlfriend, Amelia, standing on the stoop.

"Oh, hi, Mrs. Millhouse," Amelia said, twisting a strand of her long hair around a finger. "I don't mean to disturb your party. I'm just picking up Jamie."

Jamie at that moment bounded down the stairs and stood next to his mother.

"We're going out for a movie, Mom," he said, planting a quick peck somewhere near her cheek. "Don't wait up."

Melinda put a hand against her son's chest, holding gently to his windbreaker. "Wouldn't you like to bring Amelia in for a moment? You could both grab a soda, and there are some great hors d'oeuvres, if I do say so myself." She turned to Amelia and said, "You like shrimp, don't you?"

Amelia started to automatically say, "Yes, Mrs. Millhouse," while Jamie looked at his mother with a teenage mixture of dismay and disgust.

" Mom ," he said, the inflection of his voice saying everything that needed to be said. Amelia glanced at Mel and shrugged apologetically, then turned back to Jamie.

"Oh Jamie, that's so sweet," Amelia said, out of the blue. She took Jamie's hand and ran down the sidewalk with him.

Mel closed the door, but not before she heard Jamie say, " What's so sweet? Amy, what're you talking about?"--and Amelia's return laughter. Mel had also seen it, though, and watched as her fingers changed back from a round pinlike shape that had said, "My Mom's #1."

The party was finally over. As usual, the house looked like a major storm front had moved through, glasses and beer bottles and canapé plates everywhere, under furniture, in potted plants, behind bric-a-brac. Melinda would be finding them for days. Normally she would start cleaning up immediately, getting the first few loads in the dishwasher out of the way. But tonight she could hardly stand, and thought she would probably end up breaking more than she cleaned.

Fortunately, her behavior--her morphing--had passed by unnoticed. Bailey was unaware of the little waves of disturbance that had periodically passed through his party. Except for Carol Wordsworth's abrupt departure fairly early in the evening, Bailey counted the party a success. He was, however, aware that his wife had had more to drink than usual.

"Didn't the party go well?" he said, hands on hips, looking around the messy rooms with satisfaction. Then he noticed her standing there, swaying. "A little too well for some of us," he told Mel with laughter in his voice. "Off to bed with you. I'll do a bit of picking up and be right behind you." When he saw that Melinda was having difficulty navigating the stairs, however, he swept her upstairs himself, leaving the dishes behind.

Mel knew what was on Bailey's mind--Bailey was always amorous when he was pleased with himself. Despite warning herself ahead of time, as she got caught up in the passion, Mel forgot to be cautious where she placed her hands. Her morphing caught them both unawares. When Bailey looked down and said, "It's funny, I feel fine," it was too late for her to remove her hand. But then he said, "Oh, Mel, I haven't been so good to you tonight all the way around, have I?" and she felt a small, guilty twinge of satisfaction. And as Bailey kissed her behind her ear and began stroking her in a genuine feeling of contrition, she couldn't think of a way to admit her own contribution. Later, as they both drifted off in a close, companionable sleep, Mel wasn't sure if it wasn't for the best, anyway.

Mel came downstairs late the next morning in an incredibly buoyant mood, considering the deep, pounding headache her excess drinking of the night before had occasioned. Still dressed in her big fluffy robe and slippers, she descended the stairs gingerly, almost bursting with the feeling that she was a new person. An odd--a very odd--thing had happened to her yesterday. She had changed, and because of that, her life had changed.

But then she glanced down into the living room below and stopped. She sat, falling onto the step with a jarring bump that traveled from her tailbone up into her hangover.

Bailey and the boys had gone out for their usual Saturday morning round of golf, which she had been grateful for because it left the house quiet and peaceful. But all the detritus of the night before still lay spread before her, like a party wasteland. Glasses, bottles, crumpled napkins, half-eaten food, all overlaid with the smell of old beer and tobacco ash.

You'd think they could have managed to take out one lousy trash bag , Mel thought. The sight below--and what it meant--hit her hard because she hadn't expected it. Her differentness had been so obvious to her, her new power so evident at the party, she had thought everyone would now see how completely things had changed.

How could they ? Mel thought, her teeth clenched. How did you walk past a half-ton of trash without noticing it? A reasonable question that she had been ignoring for over fifteen years. What am I, chopped liver? And she looked quickly down at her hands. But rather than what she expected, Mel saw instead that her fingers, partially hidden in the folds of her chenille robe, had morphed into sharp, curved blades, deadly looking files and long, pointed knives. She hurriedly buried her hands deeper into her robe, refusing to look again. They don't realize what I am , she thought. But then she wasn't exactly sure, either.

Mel wandered through the empty, silent rooms, picking up dirty dishes, retrieving trash from behind seat cushions and wiping damp circles off of the furniture, thinking about the odd direction her life had taken. It was, she thought, like a kaleidoscope: All the pieces were the same, yet with one twist, everything appeared somehow different. But apparently, only to her.

Mel put the dishes in the sink and automatically started to rinse them. She thought better of it, however, and made herself some tea instead. She sank down into the big chair in the TV room and held her steaming mug, leaning her head back and closing her eyes.

Although on the surface, everything was the same, she thought perhaps she knew what was different. The balance of power--such an amorphous, indefinable thing--had somehow tilted back her way. And she was going to be very, very careful she didn't lose it again.

Bailey had been so loving and attentive last night, then this morning had reverted to his old behavior. She was going to have to do something about that. And the boys, well, they were still young enough to learn.

After she finished her tea, Mel got up for another mug. She looked at the crystal, and thought she'd at least fill the sink with hot, sudsy water.

Mel heard the distant rumble of the garage door opening, the slamming of car doors, the loud laughing and joking of her three men. The kitchen door burst open, and Bailey and her sons greeted her with the boisterous good humor of a morning gone well.

Mel lifted her hands from the soapy water, shaking the suds from them and drying them on the dishtowel. In the face of such exuberance, it was impossible for her not to smile in return. Yes, things were different now. Bailey and the boys just didn't know it yet. With her hands still glistening slightly from the dishwater, Mel reached out to them.

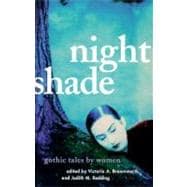

Copyright © 1999 Victoria A. Brownworth and Judith M. Redding. All rights reserved.