Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| About the Nobel Prize | vii | ||

| Introduction | ix | ||

|

|||

| How Do I Win the Nobel Prize | 1 | (10) | |

|

|||

| Why Can't I Live on French Fries? | 11 | (13) | |

|

|||

| Why Do We Have to Go to School | 24 | (14) | |

|

|||

| Why Are Some People Rich and Others Poor? | 38 | (13) | |

|

|||

| Why Do We Have Scientists? | 51 | (11) | |

|

|||

| What Is Love? | 62 | (9) | |

|

|||

| Why Do We Feel Pain? | 71 | (10) | |

|

|||

| Why Is Pudding Soft and Stone Hard? | 81 | (10) | |

|

|||

| What Is Politics | 91 | (12) | |

|

|||

| Why Is the Sky Blue | 103 | (12) | |

|

|||

| How Does the Telephone Work? | 115 | (13) | |

|

|||

| Will I Soon Have a Clone? | 128 | (13) | |

|

|||

| Why Is There War? | 141 | (14) | |

|

|||

| Why Do Mom and Dad Have to Work? | 155 | (11) | |

|

|||

| What Is Air? | 166 | (14) | |

|

|||

| Why Do I Get Sick? | 180 | (12) | |

|

|||

| Why Are Leaves Green? | 192 | (9) | |

|

|||

| Why Do I Forget Some Things and Not Others? | 201 | (15) | |

|

|||

| Why Are There Boys and Girls? | 216 | (12) | |

|

|||

| Why Does 1 + 1 = 2? | 228 | (15) | |

|

|||

| How Much Longer Will the Earth Keep Turning? | 243 | (11) | |

|

|||

| Acknowledgments | 254 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

by Mikhail Gorbachev

Dear Friend!

Do you know, actually, who invented the Nobel Prize? It was a Swede, Alfred Bernhard Nobel, himself a great scientist and outstanding inventor. He invented synthetic silk and welding with gas. His most famous invention was dynamite, and because he was not only a very smart man but also a very clever man, he opened his own manufacturing plant in which he produced dynamite. From there, he sold it to the whole world, and that is how he became very rich.

Shortly before his death, Alfred Nobel had an idea: He made a last will, and this will stated that nearly his entire immense fortune was to be used, after his death, to establish a foundation. This foundation would then have the task of awarding five large prizes each year to five outstanding men and women from the whole world -- three of them for the most important discoveries or inventions in the areas of physics, chemistry, and biology or medicine. One prize was to be for literary works that, as he said, were "the most advanced toward 'the Ideal.'" A further prize was to go to the person who managed to create peace somewhere in the world -- between two countries, for example, that had never gotten along and were at war. Much later, in 1968, a prize was started for economics, funded by the Federal Bank of Sweden on the occasion of its three-hundredth anniversary. Only the Peace Prize recipient is decided by a committee of the Norwegian Parliament; all of the other prizes are awarded by various Swedish organizations, including the Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Now, dear friend, you may think the whole thing is very strange and contradictory. A man who makes his fortune with dynamite, a deadly weapon, endows the world with prizes for things and works that are supposed to make the world wiser and happier -- like, say, Albert Einstein's discoveries in physics, or Boris Pasternak's novelDoctor Zhivago.That the "King of Dynamite," as Alfred Nobel was called by his contemporaries, was the founder of a Nobel Peace Prize must seem totally contradictory to you. I myself don't consider it a paradox. Alfred Nobel was, after all, a man of great vision; shortly before his death, he was willing to learn from his own mistakes -- something only very few are able to do. Late, but not too late in life, he understood that the fate of humankind was not supposed to be war, but peace. The same can be said of Andrei Sakharov, the ingenious Russian physicist and later a Peace Prize winner. At first Sakharov was one of the scientists who created nuclear weapons of unbelievable gruesomeness. Later on, however, he became one of the toughest and most uncompromising champions for nuclear disarmament, even risking his own health and freedom in the process.

So how do you become a Nobel laureate in the first place? To answer this question, we may have to think about it somewhat differently. We have to think about who has become a Nobel laureate to date. Let's take some of the most famous whom you've heard about already or will hear about for sure -- in physics class, for example. There, you will encounter the names of many Nobel Prize winners, names like Wilhelm Roentgen (who invented X rays -- you probably know already what an X-ray machine is), Marie Curie, Niels Bohr, and Enrico Fermi. All of them, no doubt, are the founders of modern physics. Or let's look at another area of knowledge: biology or medicine. The names of people firmly intertwined with these disciplines are Ivan Pavlov, Robert Koch, and Alexander Fleming. And have you read any books yet by George Bernard Shaw, Thomas Mann, Ernest Hemingway, or Toni Morrison? If you haven't yet, you surely will -- and not just because all of them received the Nobel Prize for literature for their great books, but because their books are truly great.

All right, those are just a few names. But I think you already understand what I mean to say: that the men and women who have become Nobel laureates are only those who have enriched human knowledge through some extraordinary contribution, who have discovered as-yet-unknown laws of nature or unimaginable secrets of human life and of man's soul. In short, they are people who have opened truly new horizons for all of us.

Among the Nobel Prize winners so far -- as you've already figured out by now -- have been many politicians and scientists who brought people peace. Alfred Nobel, of course, thought through this part particularly well, for nothing is more difficult to understand than peace -- and it is even more difficult for people to achieve. I know personally many recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize. All of them are wonderful, selfless people who spared no effort to end armed fighting, to restore peace and respect among people all over the world who seem to always be so senselessly embroiled with one another. To do this has never been simple or easy.

It is just as difficult as developing a complicated physics formula or solving an extremely challenging medical problem. Some Peace Prize winners have paid with their lives for their endurance and noble spirit -- Martin Luther King Jr. or Yitzhak Rabin, for example. Or they struggled with difficulties -- like Nelson Mandela, who sacrificed decades of his life in South Africa in the fight against apartheid. Nothing, not even prison and persecution, could dissuade him from his beliefs.

I do not want to make comparisons between myself and these men. But surely it was as much a surprise to them as it was to me when they learned that they had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Why? Because everything they did was done for the sake of humanity, not because they were striving for recognition or even for some award. Understandably, one is all the more happy about such an honor. For it is happiness to see that one has really achieved something for people -- and, above all, that the people have understood what one has oneself understood.

Do you want to know, my friend, what I understood? That war and violence were no longer supposed to be acceptable means in world politics, that no one should be threatened anymore with anybody else's weapons. From the moment that I was elected general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and thereby head of the Soviet nation, the most important question for me was this: What could be done to put an end to the nuclear arms race? How could we avert, forever, the nuclear catastrophe that for so long already had hung over humanity like the sword of Damocles? I had to begin to transform my ideas into reality literally on the day I was elected, because the next morning a new round of Soviet-American negotiations on limiting weapons was supposed to start in Geneva. For years, people had sat together and not moved an inch. People were negotiating for negotiation's sake. So I declared that at last results were needed; and to show how seriously I meant business, I soon let the Americans know that in Europe we were willing to stop positioning the most dangerous midrange missiles -- unilaterally and without any ifs, ands, or buts. Next ensued a long correspondence with then President Ronald Reagan, at first completely in secret and then a meeting with him in Geneva. At the end of these talks there were far fewer weapons in this world than before -- and much more trust between two political systems that had been enemies up to then.

Whoever brings peace to others also receives it. This was another important lesson for me from those years. Only in the light of worldwide détente, a period of relaxed tensions, were we able to begin democratic changes in the Soviet Union, such as perestroika, a policy of economic reform, and glasnost, a policy allowing more freedoms. Yes, I believe to this day that a modern country must definitely try to bring the interests of its own people in step with those of the world community. Things were different in our country for a long time. Only after we no longer felt threatened, because we had stopped threatening others, could we warm to the idea that life was much richer and more complex than the best and most perfect governmental plans. The scheme into which communism had pushed people for seventy years was actually also a form of violence. After it had all ended, somebody in Stockholm picked up the receiver and called me.

Do you know now, dear friend, how one becomes a Nobel Prize winner? Do you perhaps want to become one yourself? If you really want to know, you will succeed. You must always remain curious, never accept an answer as final -- and, above all, have faith in people, in their capacity for renewal, for solidarity, for poetry. And when one day you receive a Nobel Prize, I will take you to one of the conferences where Nobel laureates regularly meet. You and I will talk with the other laureates about how we can make people even a bit more thoughtful, science even a bit more revolutionary, literature even a bit more exciting.

And you will suddenly understand that your job as a Nobel Prize winner really only begins after you receive it.

Mikhail Gorbachev, born on March 2, 1931, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990 for his efforts to end the Cold War. He lives in Moscow and is chairman of the Foundation for Socioeconomic and Political Studies, which he founded.

Copyright © 2001 by Wilhelm Heyne Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich Essay compilation for English language edition copyright © 2003 by Ullstein Heyne List GmbH & Co. KG, Munich English translation copyright © 2003 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

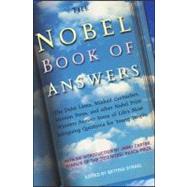

Excerpted from The Nobel Book of Answers: The Dalai Lama, Mikhail Gorbachev, Shimon Peres, and Other Nobel Prize Winners Answer Some of Life's Most Intriguing Questions for Young People by Bettina Stiekel, Jimmy Carter, Paul De Angelis

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.