Contents

1. Drinking with Daddy

2. Thunderbird off the Coast of Maine

3. The Weight of Air

4. First Love

5. We Are Always True to Brown

6. Graduation

7. Rocky Mountain Buzz

8. Drinking and the Romantic Imagination

9. Alabama 1965; Mississippi 1966

10. Fear

11. Note Found in a Bottle

12. Bow Wow

13. Beechwood

14. Parties in New York City

15. Living with the Dead

16. Fighting

17. Expatriates

18. Journalism

19. San Francisco

20. Warren After Dark

21. Opposites

22. Tais-Toi

23. Champagne

24. "I really want a drink."

25. Sarah

26. I Stop; I Start

27. The Sand at the Heart of the Pearl

28. Quad

29. The Mitchell Brothers

30. Stopping Again, Again

31. Healing

32. The Places I Went

Acknowledgments

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

My grandmother Cheever taught me how to embroider, how to say the Lord's Prayer, and how to make a perfect dry martini. She showed me how to tilt the gin bottle into the tumbler with the ice, strain the iced liquid into the long-stemmed martini glass, and add the vermouth. "Just pass the bottle over the gin," she explained in the genteel Yankee voice that had made her gift shop such a success that she was able to support her sons and husband. I watched enthralled as she twisted the lemon peel with her tiny white hands and its oil spread across the shimmery surface. I was six.

New York City in the 1940s was a postwar paradise. Soldiers brought back wonderful, exotic war souvenirs: bamboo hats from the Philippines and delicate lacquered boxes from Japan. It was all sunlight and promise and hope in those days. The streets were safe; the shopkeepers knew everyone who lived on the block. The women wore dresses and high-heeled shoes, and the men all wore brimmed felt hats trimmed with grosgrain ribbon.

Outside our windows the Queensboro Bridge rumbled with traffic. The avenues around our apartment building filled up with the rounded shapes of Buicks and Chevrolets. My father bought a secondhand Dodge for trips to the country, and he parked it across Fifty-ninth Street, right next to the bridge, so that we could admire it from the windows of our apartment. It was that car, I always thought, that wrecked our golden New York City life. In that car my parents started taking us out to visit friends who had moved from the city to the suburbs. These friends were always telling my parents how great the suburbs were. In the suburbs there were wonderful public schools. In the suburbs a young family could have their own house. In the suburbs there was plenty of outdoors for children to run around in, and a community of like-minded parents. In 1951 we moved.

Every evening at six o'clock, right on schedule -- because almost everything in those days was right on schedule -- the grown-ups in the suburbs would prepare for what they called their preprandial libation. They twisted open the caps of the clinking, golden bottles and filled the opalescent ice bucket, brought out the silver martini shaker and the heart-shaped strainer and the frosted glasses, and the entire mood would change. I loved those mood changes even then.

I loved the paraphernalia of drinking, the slippery ice trays that I was allowed to refill and the pungent olives, which were my first childhood treat, and I loved the way the adults got loose and happy and forgot that I was just a child. I loved the way the great men would sit down so close to me that I smelled their smell of tweed and cigarette smoke and whiskey and tell me their best stories about hiding in a tree at Roosevelt's inauguration, or dodging German bullets in France, or meeting Henry James as a doddering old man in a London club; and the way the women would let me play with their lipsticks and mirrors and would show off the mysterious lacy underwear that held up their silky stockings and held in their tiny waists.

I knew that, like them, I would grow up and get married. My husband would have a job in the city, and I would iron his Brooks shirts; I would learn to cook pork chops in cream sauce and to bake a Lady Baltimore cake, and I would serve cheese and crackers and nuts at parties and take care of my children. We would have a little house, just like my parents', and on vacations we would take our children to visit them just as they took us to visit Bamie in Quincy and Binney and Gram in New Haven and New Hampshire. In the evenings, I would greet my homecoming hubby with the ice bucket and the martini shaker. On Sunday mornings we would have Bloody Marys. In the summer we would stay cool with gin and tonics. In the winter we would drink Manhattans. In good times we would break out champagne, in bad times we would dull the pain with stingers. I was already well acquainted with the miraculous medicinal powers of alcohol. My mother dispensed two fingers of whiskey for stomach pain and beer for other digestive problems. Gin was an all-purpose anesthetic.

Drinking was part of our heritage, I understood. My earliest memories were of my father playing backgammon with my grandmother over a pitcher of martinis. The Cheevers had come over in 1630 on theArbella,the flagship of the Winthrop fleet. The trash came over on theMayflower,my father always said. The best Puritans, the Puritans like us waited until it was clear that the New World was a place worthy of our attention. I learned that theArbellaset sail with three times as much beer as water, along with ten thousand gallons of wine. Hemingway had called rum "liquid alchemy." Jack London and John Berryman and Dylan Thomas had written about the wonders of drinking. Brendan Behan came to visit and, with a drink in his hand, sang to me. "The bells of hell go ting-a-ling-a-ling for you but not for me," he sang. "O death where is thy sting-a-ling-a-ling, O grave thy victory?"

I found out about divorce at around the same time that I learned that the Russians, who lived on the other side of the world, had enough atomic power to blow us all up. These two ways in which my life could be shattered by outside forces wielded by irrational adults seemed equally terrifying. From what I saw around me in those idyllic suburbs, marriage was not a happy state. Often when there were parties at our house, the merriment of the first cocktails became sparring and loud arguing before the dessert was served.

By the time we had lived in the suburbs a few years, my father's suburban stories were appearing regularly inThe New Yorker.Although we couldn't afford to join a country club, or buy a new car -- all our cars were secondhand -- as a family we had a status conferred on us by my father's success. My father liked to tell divorce stories: he loved the story of how Gert Simon had left her husband while he was at work in his office in New York City -- taking the children, the furniture, and even the pets and leaving nothing at all -- so that he came back at nightfall to an empty house where he thought his home was.

Divorce was still pretty rare though. If you ask me, the grown-ups were too dressed up for the indignities of divorce court. They still had their hats on every time they went out. When they got clinically depressed, when their adulteries caught up with them, when all the martinis in the world weren't enough to blot out the pain of their humanness, they killed themselves quietly. No one talked about it. They hanged themselves with their hats on.

Copyright © 1999 by Susan Cheever

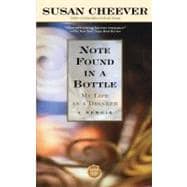

Excerpted from Note Found in a Bottle: My Life As a Drinker by Susan Cheever

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.