Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

Looking to rent a book? Rent Nude Walker A Novel [ISBN: 9781250002464] for the semester, quarter, and short term or search our site for other textbooks by Monk, Bathsheba. Renting a textbook can save you up to 90% from the cost of buying.

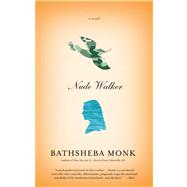

Bathsheba Monk is the author of Now You See It . . . Stories from Cokesville, PA. She lives in Pennsylvania, where she is writing her next novel and developing a musical. She writes radio essays and interviews other artists on National Public Radio’s Lehigh Valley affiliate, WDIY. Visit her online at www.bathshebamonk.com.

When I recall Afghanistan, I think of gray spiky plants with long taproots sinking into sand, shrouds of women kicking up dust as they move down the road, and skies the brittle blue of a prolonged drought. Arid. Ashy. Barren. So the sudden large cool drops made me laugh aloud as we trudged across the tarmac to board the C-128 at Bagram on the first leg of our trip home. I lifted my face to the sky to enjoy this farewell rain, which was like a kiss that would awaken the sleeping desert life.

“Bineki, did you lose this?”

I turned around. Max Asad, our unit translator, dangled a blue stone tied to a strip of black leather on the end of his index finger. “It was on the ground.”

I was so startled to see him that I grabbed the amulet, but it slipped out of my hands and I bent to pick it up again. “Thanks. It keeps coming off.” I fumbled as I tried to knot it around my neck.

“Here, let me.” He took the two pieces of leather and tied them together, his hands brushing my neck and cheek, pulling out strands of hair that got caught in the knot. “Your hair is like silk, Bineki. It keeps getting caught.”

I held my breath while he fussed over me, then I shoved the stray long hairs back into their knot under my cap. “Thanks. Again.”

I hadn’t noticed Max get in the queue and his unexpected appearance unnerved me. Actually, I hadn’t seen him in almost a year: he’d been hijacked by the Special Ops almost as soon as we landed. After one month in Kandahar, he’d moved out of the tent he shared with my boyfriend, Duck Wolinsky, and into the Ops’ barbed-wire enclave on the far end of the airfield so he could be ready to move out with them before dawn. The Ops paid native translators very well, but there was always the possibility that the enemy was paying more, so they wanted someone they could trust: that is, an American. Like all the best perks in Afghanistan, Max was theirs.

He turned me around and wiped some rain from my cheek with his thumb. “It’s sweet, the rain.”

“Yes. Sweet.”

“Where did you find it?” he asked, touching the stone.

I clasped my hand around the lapis lazuli. It seemed hot. “It was a present. A friend found it outside the wire.”

Duck had given me the stone, an intensely blue piece of lapis lazuli that he had found when he was repairing a satellite dish a couple of miles outside of Kandahar. The tie came undone easily and I’d lost it several times. Somehow, someone always managed to find it and return it to me, and it was starting to feel like a portent demanding my attention.

“You should be careful with stones. You never know what information they pick up.”

“You think stones hear things?”

“Why are you surprised? We can’t know everything. What I can’t understand, I respect at least.”

“I thought we invaded to get rid of superstition and give them good old American common sense. Et cetera.” I was trying to make him laugh, but he was so damned serious. The only other time I had spoken to Max was a year ago, almost to the day, when the 501st was having a send-off party for itself. I had cracked a joke while we were sipping orange soda out of plastic cups, and neither he nor his father had laughed. I remember his dismissive look, because I wanted him to like me.

“Is that what you think? That Americans have no superstitions?” Max shook his head.

Everything he said was so unlike what other men said. I wanted him to explain what he meant by “It’s sweet, the rain” what he meant when he said stones picked up information; why he never seemed to laugh. I didn’t understand him, and I wanted to. He wandered back to his place in line before I could answer.

After a year in Kandahar, I couldn’t say I understood the East, either. Women weren’t allowed off base without an armed male escort. So how could I claim to understand anything of a culture I never saw, a culture that measures time in generations and worth by the size of those generations, a culture whose people seem to grow out of the barren mountains, to float above the turbulence created by their many invaders—Alexander the Great, the British, the Soviets, and now us—waiting for an auspicious moment to touch down? Like everything in Afghanistan, my presence was just one more thing that would vanish in the desert, covered over with sand. Everything was ephemeral. Buildings were tents, laws were oral, and even the usual fortifications of civilization—walls—were illusions swept away in the wind of the next sand-storm.

I didn’t understand the East but I loved it, probably for that very reason. It was just out of my reach, and things you can’t own, that keep surprising you with their unknowableness, if that’s even a word, are a thousand times more exciting than things that jump in your lap.

The rain trickling down my face, the first we had the entire year we were in Afghanistan, was exciting because it was a surprise. But really, the weather was always a surprise at Bagram. The Taliban had destroyed the sophisticated weather-tracking equipment the Soviets had abandoned, claiming that only God could predict the weather, and now the base was dependent on decades-old weather balloons that the Czechs and the Canadians sent up and that Taliban raiding parties routinely shot down. The Afghanis trusted God to know the future, but their fortunes hadn’t changed since Alexander, so even I could predict what tomorrow would bring to the average Afghani. Today would bring a rain of bullets and the death of a close friend who didn’t agree with the politics of whoever was pumping the ammo. Tomorrow the Allies would rain herbicide on his poppy crop, saying it was immoral to grow a drug that the entire world wanted—a lot. Everything rained on Afghanistan, except the one thing they would have welcomed: water.

My unit, the 501st, was a supply and legal assistance company, consisting of supply personnel like me and lawyers who were helping the Afghanis write a constitution. Their highest authority was Muhammad, may he be blessed, as they say, and ours was the Constitution, may it be blessed too—why not? Right from the beginning, an idiot could see that wouldn’t go anywhere. While our JAG officers were busy explaining to the Afghanis the importance of due process with its uncertain outcomes, their mullahs were yelling “Off with her head!” It was like watching two plays performed simultaneously on the same stage, critics wildly applauding, mistaking activity for progress, mistaking chaos for a script. It would have been funny if it weren’t so screwed up.

As our queue moved slowly across the tarmac to board the plane, a muezzin’s call to prayer echoed off the hills; then suddenly the sky got inky black and the gentle rain became a downpour and drowned out all other sounds. The muezzin’s call had been part of the sound track for my year in Kandahar, along with the wailings of strange animals at night, exploding mortar shells, and the yelling that goes on in the military because everyone tries to be heard over the din of heavy machinery or is deaf from ordnance exploding near their heads. Sounds that you are forced to hear are noise. It wasn’t until that ride home that the noise stopped and the music began.

The loudest noise of all, an insistent downbeat, had been the badgering of my tentmate, Jenna Magee, who never wavered in her mission to bag my soul for Jesus. I’m an atheist—probably more like an agnostic, because who knows? Like, Afghanistan shocked the hell out of me: that a place actually exists where a person couldn’t even have a drink of water without carrying it on their head for a mile, and then the chances are pretty good that some jerk is going to shoot a hole in their bucket before they get home. I like the idea that there might be a spiritual heaven and hell, and it’s fun to speculate on which laws are the right rules of the road, so to speak. But Jenna’s brand of religion was as unambiguous as a car alarm at three in the morning. If she was right, then my indecision was wrong, and if I was wrong the consequence for me was hell—Jenna’s syllogism of salvation. The threat of hell was weirdly exciting, I have to admit, and when she would talk about Jesus taking over my life I’d answer, “Sounds good to me, great actually,” and she even had me down on my knees in the sand one evening when I was feeling—and had the bad judgment to share with her—that life could seem kind of random.

“Doesn’t it seem random to you sometimes, Jenna?” I asked her one night when I was particularly chatty from spiked Gatorade at a comrade’s birthday party. “Why do we have all this stuff and the Afghanis keep getting their stuff taken away?”

“They haven’t accepted Jesus into their lives,” Jenna had said triumphantly. “They’re like zombies, wandering aimlessly. They’re dead. You’re dead. If you ask Jesus into your life, He will take over everything. Explain everything. Nothing is left to chance. He has a plan for you. You’ll see!”

Her passion ignited mine and I said, “Great, let’s do it.” We knelt in our tent. I was thinking it would be fabulous to have a get-out-of-hell card, although it did occur to me in the throes of my would-be salvation: What happens after this? You just go around the game board collecting points and demerits until you die?

Jenna grabbed my hand and closed her eyes. “Lord Jesus, Kat Warren-Bineki knows she’s a sinner. She knows You died a bloody and horrible death to pay for her sins and she accepts Your bloody and horrible death on the cross as payment in full for her many sins. Kat Warren-Bineki knows that good works mean nothing to You, Lord, only belief. Right now, Lord, I ask You to save Kat Warren-Bineki and forgive her her many many sins and fill her heart with peace. Thank You, Lord, for saving Kat Warren-Bineki and help her live her life in a way that pleases You. In Jesus’ name. Amen.”

I was stunned that she lumped me in with all the other sinners, not mentioning my good qualities. Considering my lukewarm introduction to Jesus, as if I were just one of the hoi polloi, I wasn’t surprised when, after two minutes of squeezing my eyes and waiting for the cosmic boink, nothing happened. “It didn’t take,” I said. “Jesus did not enter the building. Anyway, all that blood-and-gore stuff is disgusting.”

“That’s how you know it’s real,” she said. “No blood, no glory. You must have felt something. How can you not have felt something?” She demanded a redo, which I declined. By then I was feeling like I was on a blind date where I liked the guy more than he liked me.

“Besides,” I said, “how can Jesus help me? He couldn’t even help himself. His own father made him do that stuff. How creepy is that?” Although, if you look through the annals of parent-child relationships, what God asked Jesus to do is typical, really.

Jenna had a trove of pamphlets that supported her beliefs, and she flipped through them until she located the one that addressed my particular unbelief, thrusting it at me.

“You’re missing the entire point. Yes, His Father asked Him to do it, but Jesus wanted to die for you. If you don’t believe that He wanted to die for you,” Jenna said, all snitty, “you’re going to burn forever in hell. You have to believe the story of Jesus dying for you or you’re screwed. Your life has no meaning. It’s just random bullshit.”

I was jealous of their passion—Jenna’s and Jesus’—but I was delighted that after the 501st was deactivated I would never have to listen to Jenna again. I was twenty-five years old, still young enough to think that things happen once and then they’re over; too young to know that human beings are, as my mother would say, a broken record.

We could sit wherever we wanted in the plane, and I found a window seat and moved into it, putting my backpack on the seat next to me, planning to move it when I saw Max coming. We were only one hundred and one people in the 501st, so there were plenty of empty seats. Jenna ambled down the aisle and stopped in front of me, picked up the backpack and handed it to me, then slipped into the seat. As there seemed to be no polite way to tell her I was hoping someone else would sit there, I bent my knees, put my feet on my seat, and hugged myself, trying to create a private space to be with my thoughts.

Reuber and Camacho, guys from downtown Warrenside, forged up the aisle. Reuber looked down and grinned at me. “Goin’ back to the world, Bineki!”

“That’s right,” I said.

Soldiers call home “the world,” as if everywhere else is just a bad dream you can hardly wait to wake from. After listening to soldiers from the 501st talking about “the world,” an alien from outer space would think Warrenside, Pennsylvania, was El Dorado instead of a has-been industrial town that spat its families out a generation ago. If Warrenside was so great, why would its scions voluntarily join the army? It’s the myth that keeps you going, that you have somewhere to go back to, a cool town whose residents can hardly wait for your return. In truth, you have lost your place in a cruel game of musical chairs. The world Reuber was returning to was light-years away from my world, but we would have the same reentry problem, because once you have gone to the bathroom in a fire latrine, you basically have nothing in common with anyone in suburbia; after you’ve convinced yourself with epithets and slander—hajji and rag head et cetera—that the people your army is trying to annihilate are subhuman, you have nothing in common with any thinking person. But unless you’re a homicidal maniac, how else can you get it up to kill someone? Not that anyone in 501st Supply and Support killed anyone, but we were ready if we had to. Goddamn, we were ready. But here’s the thing: the army may have given us night vision goggles, but they took away our ability to see gray. So what are you going to discuss over a Coffee Coolatta at Dunkin’ Donuts back in the world? Your conversational repertoire is subverbal—loading up the revolver at four in the morning and staring at your mate in the dark until she wakes up and, petrified that you’ve gone berserk, shoves the kids in the pickup and leaves. Wait, honey, you want to say, I’ve seen things! You don’t know what’s out there. I know! And all Honey knows for sure is that you’re the one with the gun and crazy ideas about how to fix things so they are black-and-white again.

“You are no longer on speaking terms with your world.” That’s what Duck used to say. “My dad was in Vietnam, so talk to him,” he always said, “if you want to know about returning to the world you almost died defending.” But you couldn’t actually ask Duck’s dad anything. He killed himself. Not in Vietnam, here. I mean, there. Home. The world.

It was pouring and our plane was still idling on the runway for what, I was beginning to suspect, would be hours. Jenna began chattering. “I am so glad to be out of here,” she said, “and to be going home where people are God-fearing. Where they can talk about Jesus without getting their heads cut off.”

“I guess they fear God here, too. That’s why they’re such fierce warriors.”

“Fierce warriors. Ha.” Jenna unzipped her Bible and turned to an underlined passage. “‘A man can only come to the Father through Me,’” she read, then closed the book. “Without Jesus, they’re just soulless bodies. They’re killing machines. They are not fierce warriors.”

“What about the part that says love thy neighbor as thyself?” I asked. “That part’s in there too, isn’t it?”

We’d had this same conversation for a year, but I was too polite to shut her off. The requirement to be polite had been drilled into me since I was a kid. It would make people feel bad, my mother said, to show up their ignorance. We had to worry about making people feel bad, because we were Warrens. According to the laws of a dominant male progenitor, I’m a Bineki, but you wouldn’t know it to be around my mother, who insisted that we hyphenate our name. Warren-Bineki. The Bineki part could be lopped off if anyone important noticed it. My dad was like a stud the Warrens brought in to pep up the stagnant gene pool, then see-ya-later. Mother never talked about the Binekis, because they were ordinary. My mother was scared of ordinary people, a fear she learned from her grandfather, who was insane on the subjects of socialism, communism, and labor unions. He never stopped warning his family about the violence of the ordinary ignorant man. Ignorant people, my mother said, were unapologetically violent.

I disagreed with my mother regarding almost everything, but in this instance I had to admit she was right. In April, Jenna, who was uncommonly ignorant, had accused Barzai Marwat, the Pashtun who worked in the Admin tent, of inappropriately touching her while she was laying a Jesus trap for his Muslim soul. When she complained, our commander, Captain Whynnot, handed Barzai back to the Afghani warlord who owned him, and within twenty-four hours he was hanging on the town soccer field as an example. After I grilled her later, Jenna admitted the inappropriate touching consisted of the Pashtun’s pulling a strand of her frizzy red hair through his fingers and laughing—he had never seen anything like it. That was it. He touched Jenna’s spectacularly ugly orange hair. For that, Barzai died. After it happened, I asked Jenna if she felt remorse about Barzai’s execution; she said if he accepted Jesus into his heart before he died, he could apologize to her in heaven for touching her.

I thought Jenna was lost in her holy thoughts when she said, “I was kind of open, sexually, like you, before I found Jesus. So I don’t regret any of it. It was His way of finding me, I guess.” She leaned in as if we were intimates. “He’s looking for you, Kat.”

“Sexually open? Are you insane? Duck’s my boyfriend. Everyone knows that.” I’m not bragging, but I am very sexy-looking and people—people who either want me or want to look like me—think I’m easy. I’m not. I’m one of those people other people use like a blank page for their fantasies.

Jenna opened her Bible angrily. She was jealous that I had a boyfriend and she didn’t. After the Barzai incident most of the guys were overly polite to her, but that’s it. They weren’t taking any chances.

Anyway, it was ridiculous to think of Jenna as being sexually open. The entire time we were in Afghanistan, she never took off her long underwear. I don’t think she got naked even to shower. I imagined she had three nipples or some other deformity. There was an otherwise perfectly normal girl in Basic Training who had an extra nipple underneath her left breast. She showed it off, as if it gave her extra sexual cachet. Of course, Jenna would see it as the mark of the Beast or something.

I got up from my seat, banged my head on the overhead, and wiggled over Jenna into the aisle.

“Hand me my backpack, will you?” I saw an empty seat farther up the plane. “I want to get some sleep.”

Most of the soldiers were sleeping, their bodies contorted in positions any normal person would find crippling. I found out in Basic Training that if I wanted to sleep I couldn’t always wait for a bed with sheets. Being able to fall asleep standing up was the most useful thing I learned on active duty.

I squeezed into an empty window seat a minute before we were cleared for takeoff, and in a while we were above the storm clouds, the snowy peaks of the Hindu Kush looming in the distance. I had to start thinking of Afghanistan as “there” instead of “here,” and I willed my internal compass to shift as the plane climbed higher, separating me from Afghanistan. I tried to sleep, but the agitation of the soldier sitting across the aisle from me, obviously having a bad dream, kept me awake. When he let out a scream I got up, worked my way to the back of the plane, where Camacho, Reuber, and Duck were playing poker, and plopped into a seat behind them.

Camacho and Reuber lived on the same street in Warrenside. They were inseparable best friends the entire time they were in Kandahar until the last few weeks, when they were always fighting, as if to settle who owned that street before they returned. Talk about a booby prize.

They both had contracts in their duffels for three thousand dollars a month from the recruiter for Charon Corp, the private contractor that had a lock on independent enterprises in Kandahar, such as the laundry, food concessions, road construction, and private security guards. Three thousand dollars a month was an unheard-of amount of money in Warrenside. My family had seen to that. Three thousand dollars a month would solve all their problems, they thought. Poor people always think that money is going to solve their problems, that happiness rides into town on a pile of greenbacks.

Camacho and Reuber were smoking the Cuban cigars and drinking the twelve-year-old Jim Beam that the Charon recruiter had stuffed in their duffel bags for the ride home. They were drunk and seemed to be enjoying the sensation, for the first time in their lives, of having a high-rolling suitor validate their worth.

Duck came over and leaned against my seat. “You okay, babe?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “I had to get away from Jenna.”

“You think about what we discussed last night?” he asked.

What we’d discussed last night was that we should move out of our parents’ homes and get married. We had known each other since we were six, Duck pointed out needlessly, as if knowing each other forever was a giant plus. Duck had always assumed we would get married, and I couldn’t think of a good reason why we shouldn’t, except for this irritable voice inside of me that kept whispering, This is it? No more? I pictured a vault door slamming shut while I practiced shallow breathing to ration the oxygen that had to last the rest of my life. Airtight safe.

A part of me wanted to risk my safe haven to see what else was out there, but I was afraid—of what, I couldn’t say. And Duck assured me that rumors of an exciting life outside our bunker only meant that it was full of peril. People leave you, he said. People let you down. Sometimes I imagined that I could experience the world while safely married to Duck, but when I was with Duck, the only experience I had was…Duck. When I joined the Guard to escape my mother before I became infected with whatever infected her, Duck joined the next day, shuttering his thriving cabinet shop in Warrenside. He wanted to make sure I was all right. Protect his investment. I didn’t speak to him for three weeks after that, because, after all, Duck was one of the things I wanted to get away from. But I couldn’t stay mad. Duck is Duck.

He’d said last night we weren’t going to find anyone better. We were only in our twenties and we weren’t going to find anyone better? Maybe he was right. The men my mother found to distract me from Duck were like aliens. Once, I came home from high school and there was a boy, Jason, from Massachusetts with his mother in our living room. They were having drinks as if driving six hours to have a vodka martini in Pennsylvania was a normal thing to do. Our great-great-great-great-grandfathers came over on the same boat from England, which my mother thought gave us something in common but which would make them, I told her—after I drove Jason off with my boorish behavior—fellow religious misfits, and probably fourth cousins. Hadn’t there been enough inbreeding? I asked her.

My mother told me they were the richest family in Marble-head, Massachusetts. They made their money in textiles, although the factories had been sold decades ago and they were now living on dividends from bank stocks, et cetera. When I asked Jason what he wanted to do after college, he looked at me like I was crazy. Part of me was being mean, but part of me really wanted to know, because I was going to have the same problem. I would never have to work. Thanks to my mother’s indiscretion in marrying my father, we weren’t rich-rich—like my second cousin Alix Warren, who once hired a mariachi band on the spur of the moment for a week-long party—but we were rich enough that, if I was prudent, I would never have to do an honest day’s work. I would have just enough money to paralyze me. If you have a burning desire to do something—like if you know you just have to make movies or you have to draw apples or think about Aristotle—then not having to do anything else is probably a great thing. But most people aren’t like that. Most people have to dream up ways to get money, and that ends up being their life, and then they claim it was what they wanted to do all along and they find ways to be happy about it. Which isn’t a bad thing, it’s just ordinary.

I always wanted to experience exotic cultures. I pictured myself a reincarnated Michael Rockefeller, going into unexplored territories like New Guinea—not getting eaten by the natives like he did, of course—but when I actually found myself in an exotic place, Afghanistan, aside from a few forays with armed male escorts to the local Saturday bazaar that was just outside the gate, I was required to stay within the barbed-wire perimeters of the post and go to parties at the mess hall for made-up events and drink the spiked Gatorade just like all the other soldiers. I had all this interest in the Afghani people, but I wasn’t even allowed to talk to them. I would have very much liked to hear what they had to say about me, although I can see now that as far as they were concerned I was just one more thing that crashed uninvited into their lives, something that would eventually go away.

What I respected about Duck then was that he was unapologetically ordinary. He was a rock. He had a normal carpentry business and a normal guy’s enthusiasm for hunting, fishing, and paying his bills on time, which was a big point of honor with him. Men liked him because he did things well. Women wanted to marry him, because they interpreted his reserve as self-possession, and they were jealous of me and thought I was a bitch because I was stringing him along. Did their jealousy arouse my passion? No. Of course I loved Duck, but I didn’t feel passion, which I thought was like you had to be with that person or you would kill yourself, like Romeo and Juliet.

With Duck I never felt that desperation. But wasn’t that a good thing? I had enough tumult in my life with my mother’s instability that I thought one more tumultuous thing would probably unseat me. I tried, stupidly, to talk to her about Duck before I left for Afghanistan—should I marry him? et cetera—and she just said she’d read in an article in Redbook that what first attracted you to a person was the thing you would cite in divorce court as the reason you could no longer stand him. Look at me and your father, she said, our attraction was purely lust. And now she couldn’t stand for him to touch her. That’s when I lost it. Dad was great and she was lucky to have found someone to put up with her! I yelled and screamed and kicked her heirloom loveseat and knocked out one of the legs. The whole ugly sofa just kind of collapsed in slow motion with dust from about a thousand years ago rising up, making us both choke. You would have thought I kicked her, she got so hysterical. “That was to be yours!” she kept screaming, as if I had my eye on it, which I certainly did not. See, that’s what you do when you have money and you don’t have a job: you read magazines written for women who don’t have a clue how to live their lives. And then she said, I forbid you to marry Duck.

Forbid! I stormed out of the house and got my bike, which I ride when I’m pissed off, out of the garage, and pedaled wildly across the Harlan Gardiner Bridge to the south side of town and got a flat tire on a piece of glass in front of the army recruiting station. The staff sergeant who came outside to see what all the swearing was about told me he’d fix the tire while I relaxed and watched a DVD about women in the army. In this film the women were fixing planes, flying planes, and shooting other people’s planes out of the sky. “That looks so cool,” I’d said to the staff sergeant, totally buying into the probability that I was a woman warrior, and he looked me right in the eye and said, “You have no idea how cool.”

I reached out and squeezed Duck’s hand. “Let’s talk about it later, after we land.”

“I don’t know what we’re waiting for.”

“Duck, you in or out?” Reuber shouted over the seat.

“Fold. I’m out. I’m saving my money.” Of course. He was saving his money for our future. That’s exactly what he would do. He would make a list to facilitate our future together and check off each item until we achieved, relentlessly and inevitably, domestic bliss. He looked so happy with himself that I felt guilty for being the lone woman on the planet who couldn’t seem to appreciate a man who wanted more than anything to take care of her. I was honest with Duck. I told him I didn’t feel romantic about him, but Duck said romance was for children, that romantic love had a life as brief as a two-hour movie. But don’t you love me? he’d asked. I know you love me. And I said, honestly, I would be lost without you, and he said, Then we got lucky. What the hell else do you want?

Now he touched the lapis lazuli that Max had retied around my neck. “Come on. Let’s watch these guys play.” And he dragged me into the seat opposite Reuber and Camacho.

“It’s you and me, pard,” Reuber said loudly to Camacho. “Mano a mano.” He flicked his cigar like a gangsta and turned to me and laughed nervously. Reuber was a chronic gambler. He bet on sporting events, dogfights the Afghanis staged outside the wire, anything and everything that had an uncertain outcome. A couple of years ago he gambled and lost on Linda Pasko, a rerecovering coke addict he’d met when he’d wandered into a Narcotics Anonymous meeting in the church basement while waiting for his Gamblers Anonymous meeting to begin. He’d married Linda when the 501st was activated, and her picture, along with the picture of their kid (who he wasn’t allowed to see) was now in another—luckier—soldier’s duffel bag. No one in the 501st liked to be around him, because there is a superstition in the military that bad luck is contagious, but everyone loved to gamble with him because he could be relied on to lose all his money.

“You wanna go mano a mano, pato?” Camacho said. “Let’s just cut cards.”

“Temper, temper, Camacho.” Reuber laughed.

“A thousand bucks a cut,” Camacho said. “Cut the cards, pato.”

Reuber fanned the deck out in front of him. He studied the arc of cards. He looked at our faces: Duck had straightened up to watch; Camacho was staring at him coldly. He checked to make sure I was watching too, then laughed loudly, closed his eyes, and with his index finger pulled a card out of the line. He waved his hand over it like a magician and turned it over. A five of hearts. He groaned.

Camacho reached out quickly, picked up a card, and turned it over. A three of clubs.

Reuber jumped up and did a little dance, his hands clasped above his head. “Yip yip yip,” he crowed. “Wanna go again, pard?” he said.

“Fuck!” Camacho screamed. He fanned in the cards and tossed them on the floor.

“Pick them up!” Reuber commanded.

“You pick them up, asshole.” Camacho stepped up to Reuber, bumped him with his chest, and shoved him into the empty seat.

“Pay up!” Reuber shouted. He stood up and pulled a Nepalese kukri knife he’d bought as a souvenir out of an ankle holster.

“You gonna use that thing on me, maricón? You’d better be good,” Camacho said.

Soldiers had spilled into the aisles and were jostling for positions to watch. Duck stepped between them.

“I don’t think I’ve ever known two bigger assholes,” he said. “Did either of you ignorant fucks even read your contracts? You don’t see a penny of the money until your sorry asses deplane in Baghdad. Then the money gets deposited into your bank accounts, which I’m sure neither of you even have.”

They looked stunned; then Camacho laughed. “Sorry, pato.”

“You cheated me, you fucker. I’ll kill you!” Reuber screamed.

“Hey,” Duck said. “You guys want to get Article 15s when you’re a couple days away from being done with this shit? What idiots.” He pointed at the knife. “Give me that,” he said.

“It’s personal property. I paid for it myself.”

“It’s not yours anymore. Handle first,” he said. Then he settled them down in separate seats like a father separating his squabbling children.

Watching Camacho and Reuber fight upset me, because it was a reminder of what was waiting for all of us back home. How could you be gone from your life for a year and not expect the seams to tear when you tried to squeeze back in? Personally, I would have been glad for the year I was able to defer my life, but really, my life—Duck Wolinsky—was right there, looking at me to see if I approved of how he’d handled those two delinquents.

I was walking back up the aisle, searching each row for my backpack, when I saw Max Asad’s black head dip into the aisle to pick up something he’d dropped. It looked like a piece of paper fell from a book he was reading. I stopped, thinking of what to say. I wanted to erase the bad impression I’d made on the tarmac. I had met Max at the 501st’s going-away party a year ago at the Armory, where he had stood awkwardly with his father, both with drinks in their hands, both clearly not knowing how to mingle in a crowd of enlisted men who were trying to control unruly children and chubby wives who couldn’t stop crying. Wiry white hair swirled around his father’s head like needles on a parched desert plant. He wore his trench coat draped over his shoulders, his elegance and grooming almost transforming his ugliness. Max, with his slender, graceful build and face—as smooth and tan as a ripe olive—right off a Persian frieze, wore his desert fatigues as if Armani designed them. He seemed like the only person in the room, besides me, who was truly alive. His brown eyes were slightly hooded as if something—no, everything—amused and disappointed him at the same time. It felt like a challenge, because I knew I wouldn’t disappoint him. I wanted to make him smile. At me. Only. I watched him introduce his father to Captain Whynnot, and his father bowed his head slightly and shook Whynnot’s hand, then casually turned away, uninterested. Max caught me staring at him, and he smiled and bowed slightly, that same amused look on his face, but he didn’t make his way over to me as any other man would have. So I made my way over to him. I had to know who was inside that amused look.

“Your family isn’t here?” he asked.

My mother had some imaginary—in my opinion—reaction to a new medication and couldn’t leave the house, and my father had to work.

“My dad is coming later,” I lied. “He couldn’t get free.”

He looked at me steadily. Just about the entire town was here to send off the 501st. “He must have an important job,” he said.

While my father certainly thought his job was important, all his tales of office triumphs were of how he, once again, fended off the process engineers who were trying to consolidate, automate, and eliminate his position. “It’s just a bad time.”

I waited for him to introduce me to his father, but his father turned away from me.

“You have to excuse him,” Max said. “He still isn’t used to women doing men’s jobs. He doesn’t know how to treat you.”

Then Max’s father pulled Max away as if I were radioactive at the same time Duck thought of something urgent to tell me and was tugging me in the other direction, saying, “I’m surprised that an Arab would join up.” It didn’t matter. I thought we would have a year to clear up our unfinished business. But I never saw Max, much less had a chance to speak to him, the entire time I was in Kandahar. That first month I was busy setting up shop, and when I went to find him he was already gone, plucked by the Ops. I found out from Jenna, who kept the unit’s personnel records, that he had graduated from Princeton and was fluent in Dari and Pashto, the languages of the tribes around the base. His father, as everyone in Warrenside knew, owned most of downtown, which included a strip club, a crime for which old Warrenside would never forgive him. My own dear mother had led the campaign to deny the Asads’ application to the Lenape Country Club, saying they had no class because of that strip club. All you do at the country club is play golf and tennis and get drunk with people exactly like you, so who won that round? I knew some of the men from the country club went to the strip club after business dinners or when their wives were out of town. Anyway, if being rich was the criterion for class, and I could never discern another, the Asads had become the classiest family in Warrenside. So Max had even less financial reason than me to join the army, especially as an enlisted man, and I wanted to ask him why he did it. At least that was the excuse I gave myself for intruding on him. He unnerved me unlike any man had before, so I practiced what I was going to say before I approached his seat.

“Everyone’s playing poker,” I said. “Don’t you want to play?”

“It’s not sport to take advantage of children.”

Duck had told me Max believed he was better than everyone. I sat down next to him, unnaturally unsure of myself, just as Melanie Martin, our embed from Channel 3, came up the aisle. She broke into a toothy smile. “Great,” she said. “You’re awake. You’re the only one I don’t have on tape.” She pointed a small video camera at Max, who held up his hand.

“You think I am in a zoo?” he asked.

“I have to interview everyone in the unit. It’s my job. It’ll just take five minutes.”

He closed his book and folded his hands over it.

“Come on,” Melanie said. “Everyone else did it.”

Melanie had done a video portrait of me and I hated it. I guess that’s another thing I have to agree with my mother about: never allow other people to define you, especially the media. That’s what an interviewer does: takes what you say and edits and rearranges and deletes until you look like one of those ransom notes with the words and letters cut out of different magazines. We talked for an hour with her damn camera on and I told her I wanted to travel and do some good. I was sincere, but she made me come off as a princess, and it really affected how everyone in the unit looked at me.

“So?” she asked sweetly, peering into the pop-out LED screen. “What did you do in Kandahar, Max?”

“You could have joined me on patrol anytime and found out,” he answered. It was the joke in the unit that Melanie would never put her butt on the line. The only reason she’d taken the assignment was that covering a war zone was the only way for a reporter right out of college to get noticed by the bigger stations. Everyone wanted the same plum assignments. Television reporting was like anything else: your good fortune was someone else’s bad.

“No, really,” she said. “What did you do? I mean, what was your job?”

“I was in a war,” he said. I could hear the violence in Max’s voice. It made Melanie back away. The rest of the 501st were supply personnel, like me, or lawyers and legal aides who were, as I said, helping the Afghanis draft a constitution. Max was the only member of the 501st who actually saw action, and one of the things you learn early in the military is that the only people who brag about what they have seen or done in combat are folks who have actually seen and done nothing. If you’ve been there you’d rather forget it, if you can. I’d only heard snippets of what the Ops did on patrol, and it was dirty.

“Okay. Great. Weren’t you like a translator or something?” She smiled encouragingly at him and swirled her free hand, palm up, as if to stir up his sluggish memories.

“Yes,” Max said, smiling for the first time. He seemed to find the whole thing amusing all of a sudden. “Or something.”

“So, what are you going to do when you get home?” she asked. It was the question everyone had been asking themselves and one another in the month since we got our orders. What are you going to do? It had only been a year, but already half the unit had been laid off from their jobs via e-mail.

“I will take over my father’s businesses so he can go back to his scholarly work. Okay?” Max cut the air with his hand. “Enough.”

In the month when Max was still bunking with him, Duck had told me that Max’s father, Dr. Edward Asad, was a famous scholar and had in fact written nine books about Arabic literature, but that meant nothing to me. “Is that what you want?” I asked after Melanie had thanked him cheerily and moved away. “To take over your father’s businesses?”

Max took his time examining my face, my hair, my neck, and then my hands, which were folded on my lap, and frowned.

He inhaled loudly and said, “You know what I thought of, the first time I saw you? I thought how much a girl like you would fetch in a harem.” He seemed to be enjoying himself. “I think ten sheep and four camels. No, fifteen sheep.”

I closed my eyes, imagining myself in harem pants and the payment arriving on my mother’s front lawn. “That’s actually not a very good price.”

“The most famous concubine in Suleiman the Magnificent’s harem was Roxelana. She was a Pole too, Bineki. It’s a natural attraction, the North and the South. The North is the land of ice; the South, the land of fire and passion. If ice mates with ice, there is only more ice. And if fire mates with fire, there is a conflagration. But ice and fire make water and life.”

I felt like he was drawing me under some kind of exotic veil and it was just us on the plane. I think I knew at that moment that I didn’t belong under that veil, but the fact that it was forbidden made me want it. “Did you just make that up?”

He laughed. “Westerners know nothing of Arab culture, and they don’t think they need to. That’s why we’ll be mired in the Middle East for decades. No, I didn’t just make that up. It’s Tayeb Salih, the most famous novelist writing in Arabic. You never heard of him, of course.”

Why should I have? The winners write the history books, and the West was still the winning team. “I’ll look him up in the library when I get home,” I said.

“I’m sure you won’t find his books in the Warrenside Public Library. The section on Arab literature is quite small.”

I nodded, trying to place the Arab section in the library, which I actually frequented, then felt embarrassed again because there was no such section and he knew it.

“Roxelana was his slave. Suleiman conquered all of Eastern Europe, and Roxelana was one of many slaves. He freed her and married her eventually.”

“I’m only half Polish,” I said. “My mother is a Warren.” He had made me say the one thing I’d spent my entire life disowning: that being a Warren meant anything whatsoever. Did he really think he could make me his slave? Who did he think he was? No wonder everyone hated him. I stood up.

“You are really nothing like Roxelana,” he said hastily. “I can see it now.”

“Believe me, you’re not Suleiman the Magnificent,” I said.

Duck, who had been watching from a couple of seats away, came over to us. “Hello, Asad,” he said.

“Wolinsky,” Max answered.

“What are you two talking about?” Duck asked.

I felt guilty, like I was betraying Duck for having what was a completely innocent conversation. If anyone was recording our conversation, they would find nothing whatsoever wrong with what we said. I told myself that. Yet I felt it was the most personal conversation I’d ever had, and Duck had caught us. In flagrante converso.

“Ready for the big day?” Duck asked him.

“What day?” I asked, looking from Duck to Max while Duck blathered about Max’s intended, hand-picked for Max by his father from his mother’s village in Lebanon. She was in Warrenside right that instant, selecting white tulle concoctions and ordering a five-tier cake held up with Doric columns. I could picture the little figurines on top of that cake: a plastic Arabian prince and a woman in a burka. Well, good luck to her. Duck was clearly waiting for me to congratulate Max.

“Fire and fire make a conflagration,” I said. “Isn’t that right, Suleiman?”

Max scowled.

“What? Hey, we’re getting married too,” Duck said, ignoring that I hadn’t actually said I would. He patted my head—as if I was a dog—and my face burned red. “Come on with me, Kat,” Duck said. “There’s a couple of seats in the back.”

I stood up meekly. Max grabbed my wrist and squeezed it until I looked at him. His eyes were alight. “And ice and ice is a frozen life, Roxelana.”

I yanked my arm away and followed Duck.

NUDE WALKER Copyright © 2011 by Bathsheba Monk

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

When I recall Afghanistan, I think of gray spiky plants with long taproots sinking into sand, shrouds of women kicking up dust as they move down the road, and skies the brittle blue of a prolonged drought. Arid. Ashy. Barren. So the sudden large cool drops made me laugh aloud as we trudged across the tarmac to board the C-128 at Bagram on the first leg of our trip home. I lifted my face to the sky to enjoy this farewell rain, which was like a kiss that would awaken the sleeping desert life.

“Bineki, did you lose this?”

I turned around. Max Asad, our unit translator, dangled a blue stone tied to a strip of black leather on the end of his index finger. “It was on the ground.”

I was so startled to see him that I grabbed the amulet, but it slipped out of my hands and I bent to pick it up again. “Thanks. It keeps coming off.” I fumbled as I tried to knot it around my neck.

“Here, let me.” He took the two pieces of leather and tied them together, his hands brushing my neck and cheek, pulling out strands of hair that got caught in the knot. “Your hair is like silk, Bineki. It keeps getting caught.”

I held my breath while he fussed over me, then I shoved the stray long hairs back into their knot under my cap. “Thanks. Again.”

I hadn’t noticed Max get in the queue and his unexpected appearance unnerved me. Actually, I hadn’t seen him in almost a year: he’d been hijacked by the Special Ops almost as soon as we landed. After one month in Kandahar, he’d moved out of the tent he shared with my boyfriend, Duck Wolinsky, and into the Ops’ barbed-wire enclave on the far end of the airfield so he could be ready to move out with them before dawn. The Ops paid native translators very well, but there was always the possibility that the enemy was paying more, so they wanted someone they could trust: that is, an American. Like all the best perks in Afghanistan, Max was theirs.

He turned me around and wiped some rain from my cheek with his thumb. “It’s sweet, the rain.”

“Yes. Sweet.”

“Where did you find it?” he asked, touching the stone.

I clasped my hand around the lapis lazuli. It seemed hot. “It was a present. A friend found it outside the wire.”

Duck had given me the stone, an intensely blue piece of lapis lazuli that he had found when he was repairing a satellite dish a couple of miles outside of Kandahar. The tie came undone easily and I’d lost it several times. Somehow, someone always managed to find it and return it to me, and it was starting to feel like a portent demanding my attention.

“You should be careful with stones. You never know what information they pick up.”

“You think stones hear things?”

“Why are you surprised? We can’t know everything. What I can’t understand, I respect at least.”

“I thought we invaded to get rid of superstition and give them good old American common sense. Et cetera.” I was trying to make him laugh, but he was so damned serious. The only other time I had spoken to Max was a year ago, almost to the day, when the 501st was having a send-off party for itself. I had cracked a joke while we were sipping orange soda out of plastic cups, and neither he nor his father had laughed. I remember his dismissive look, because I wanted him to like me.

“Is that what you think? That Americans have no superstitions?” Max shook his head.

Everything he said was so unlike what other men said. I wanted him to explain what he meant by “It’s sweet, the rain” what he meant when he said stones picked up information; why he never seemed to laugh. I didn’t understand him, and I wanted to. He wandered back to his place in line before I could answer.

After a year in Kandahar, I couldn’t say I understood the East, either. Women weren’t allowed off base without an armed male escort. So how could I claim to understand anything of a culture I never saw, a culture that measures time in generations and worth by the size of those generations, a culture whose people seem to grow out of the barren mountains, to float above the turbulence created by their many invaders—Alexander the Great, the British, the Soviets, and now us—waiting for an auspicious moment to touch down? Like everything in Afghanistan, my presence was just one more thing that would vanish in the desert, covered over with sand. Everything was ephemeral. Buildings were tents, laws were oral, and even the usual fortifications of civilization—walls—were illusions swept away in the wind of the next sand-storm.

I didn’t understand the East but I loved it, probably for that very reason. It was just out of my reach, and things you can’t own, that keep surprising you with their unknowableness, if that’s even a word, are a thousand times more exciting than things that jump in your lap.

The rain trickling down my face, the first we had the entire year we were in Afghanistan, was exciting because it was a surprise. But really, the weather was always a surprise at Bagram. The Taliban had destroyed the sophisticated weather-tracking equipment the Soviets had abandoned, claiming that only God could predict the weather, and now the base was dependent on decades-old weather balloons that the Czechs and the Canadians sent up and that Taliban raiding parties routinely shot down. The Afghanis trusted God to know the future, but their fortunes hadn’t changed since Alexander, so even I could predict what tomorrow would bring to the average Afghani. Today would bring a rain of bullets and the death of a close friend who didn’t agree with the politics of whoever was pumping the ammo. Tomorrow the Allies would rain herbicide on his poppy crop, saying it was immoral to grow a drug that the entire world wanted—a lot. Everything rained on Afghanistan, except the one thing they would have welcomed: water.

My unit, the 501st, was a supply and legal assistance company, consisting of supply personnel like me and lawyers who were helping the Afghanis write a constitution. Their highest authority was Muhammad, may he be blessed, as they say, and ours was the Constitution, may it be blessed too—why not? Right from the beginning, an idiot could see that wouldn’t go anywhere. While our JAG officers were busy explaining to the Afghanis the importance of due process with its uncertain outcomes, their mullahs were yelling “Off with her head!” It was like watching two plays performed simultaneously on the same stage, critics wildly applauding, mistaking activity for progress, mistaking chaos for a script. It would have been funny if it weren’t so screwed up.

As our queue moved slowly across the tarmac to board the plane, a muezzin’s call to prayer echoed off the hills; then suddenly the sky got inky black and the gentle rain became a downpour and drowned out all other sounds. The muezzin’s call had been part of the sound track for my year in Kandahar, along with the wailings of strange animals at night, exploding mortar shells, and the yelling that goes on in the military because everyone tries to be heard over the din of heavy machinery or is deaf from ordnance exploding near their heads. Sounds that you are forced to hear are noise. It wasn’t until that ride home that the noise stopped and the music began.

The loudest noise of all, an insistent downbeat, had been the badgering of my tentmate, Jenna Magee, who never wavered in her mission to bag my soul for Jesus. I’m an atheist—probably more like an agnostic, because who knows? Like, Afghanistan shocked the hell out of me: that a place actually exists where a person couldn’t even have a drink of water without carrying it on their head for a mile, and then the chances are pretty good that some jerk is going to shoot a hole in their bucket before they get home. I like the idea that there might be a spiritual heaven and hell, and it’s fun to speculate on which laws are the right rules of the road, so to speak. But Jenna’s brand of religion was as unambiguous as a car alarm at three in the morning. If she was right, then my indecision was wrong, and if I was wrong the consequence for me was hell—Jenna’s syllogism of salvation. The threat of hell was weirdly exciting, I have to admit, and when she would talk about Jesus taking over my life I’d answer, “Sounds good to me, great actually,” and she even had me down on my knees in the sand one evening when I was feeling—and had the bad judgment to share with her—that life could seem kind of random.

“Doesn’t it seem random to you sometimes, Jenna?” I asked her one night when I was particularly chatty from spiked Gatorade at a comrade’s birthday party. “Why do we have all this stuff and the Afghanis keep getting their stuff taken away?”

“They haven’t accepted Jesus into their lives,” Jenna had said triumphantly. “They’re like zombies, wandering aimlessly. They’re dead. You’re dead. If you ask Jesus into your life, He will take over everything. Explain everything. Nothing is left to chance. He has a plan for you. You’ll see!”

Her passion ignited mine and I said, “Great, let’s do it.” We knelt in our tent. I was thinking it would be fabulous to have a get-out-of-hell card, although it did occur to me in the throes of my would-be salvation: What happens after this? You just go around the game board collecting points and demerits until you die?

Jenna grabbed my hand and closed her eyes. “Lord Jesus, Kat Warren-Bineki knows she’s a sinner. She knows You died a bloody and horrible death to pay for her sins and she accepts Your bloody and horrible death on the cross as payment in full for her many sins. Kat Warren-Bineki knows that good works mean nothing to You, Lord, only belief. Right now, Lord, I ask You to save Kat Warren-Bineki and forgive her her many many sins and fill her heart with peace. Thank You, Lord, for saving Kat Warren-Bineki and help her live her life in a way that pleases You. In Jesus’ name. Amen.”

I was stunned that she lumped me in with all the other sinners, not mentioning my good qualities. Considering my lukewarm introduction to Jesus, as if I were just one of the hoi polloi, I wasn’t surprised when, after two minutes of squeezing my eyes and waiting for the cosmic boink, nothing happened. “It didn’t take,” I said. “Jesus did not enter the building. Anyway, all that blood-and-gore stuff is disgusting.”

“That’s how you know it’s real,” she said. “No blood, no glory. You must have felt something. How can you not have felt something?” She demanded a redo, which I declined. By then I was feeling like I was on a blind date where I liked the guy more than he liked me.

“Besides,” I said, “how can Jesus help me? He couldn’t even help himself. His own father made him do that stuff. How creepy is that?” Although, if you look through the annals of parent-child relationships, what God asked Jesus to do is typical, really.

Jenna had a trove of pamphlets that supported her beliefs, and she flipped through them until she located the one that addressed my particular unbelief, thrusting it at me.

“You’re missing the entire point. Yes, His Father asked Him to do it, but Jesus wanted to die for you. If you don’t believe that He wanted to die for you,” Jenna said, all snitty, “you’re going to burn forever in hell. You have to believe the story of Jesus dying for you or you’re screwed. Your life has no meaning. It’s just random bullshit.”

I was jealous of their passion—Jenna’s and Jesus’—but I was delighted that after the 501st was deactivated I would never have to listen to Jenna again. I was twenty-five years old, still young enough to think that things happen once and then they’re over; too young to know that human beings are, as my mother would say, a broken record.

We could sit wherever we wanted in the plane, and I found a window seat and moved into it, putting my backpack on the seat next to me, planning to move it when I saw Max coming. We were only one hundred and one people in the 501st, so there were plenty of empty seats. Jenna ambled down the aisle and stopped in front of me, picked up the backpack and handed it to me, then slipped into the seat. As there seemed to be no polite way to tell her I was hoping someone else would sit there, I bent my knees, put my feet on my seat, and hugged myself, trying to create a private space to be with my thoughts.

Reuber and Camacho, guys from downtown Warrenside, forged up the aisle. Reuber looked down and grinned at me. “Goin’ back to the world, Bineki!”

“That’s right,” I said.

Soldiers call home “the world,” as if everywhere else is just a bad dream you can hardly wait to wake from. After listening to soldiers from the 501st talking about “the world,” an alien from outer space would think Warrenside, Pennsylvania, was El Dorado instead of a has-been industrial town that spat its families out a generation ago. If Warrenside was so great, why would its scions voluntarily join the army? It’s the myth that keeps you going, that you have somewhere to go back to, a cool town whose residents can hardly wait for your return. In truth, you have lost your place in a cruel game of musical chairs. The world Reuber was returning to was light-years away from my world, but we would have the same reentry problem, because once you have gone to the bathroom in a fire latrine, you basically have nothing in common with anyone in suburbia; after you’ve convinced yourself with epithets and slander—hajji and rag head et cetera—that the people your army is trying to annihilate are subhuman, you have nothing in common with any thinking person. But unless you’re a homicidal maniac, how else can you get it up to kill someone? Not that anyone in 501st Supply and Support killed anyone, but we were ready if we had to. Goddamn, we were ready. But here’s the thing: the army may have given us night vision goggles, but they took away our ability to see gray. So what are you going to discuss over a Coffee Coolatta at Dunkin’ Donuts back in the world? Your conversational repertoire is subverbal—loading up the revolver at four in the morning and staring at your mate in the dark until she wakes up and, petrified that you’ve gone berserk, shoves the kids in the pickup and leaves. Wait, honey, you want to say, I’ve seen things! You don’t know what’s out there. I know! And all Honey knows for sure is that you’re the one with the gun and crazy ideas about how to fix things so they are black-and-white again.

“You are no longer on speaking terms with your world.” That’s what Duck used to say. “My dad was in Vietnam, so talk to him,” he always said, “if you want to know about returning to the world you almost died defending.” But you couldn’t actually ask Duck’s dad anything. He killed himself. Not in Vietnam, here. I mean, there. Home. The world.

It was pouring and our plane was still idling on the runway for what, I was beginning to suspect, would be hours. Jenna began chattering. “I am so glad to be out of here,” she said, “and to be going home where people are God-fearing. Where they can talk about Jesus without getting their heads cut off.”

“I guess they fear God here, too. That’s why they’re such fierce warriors.”

“Fierce warriors. Ha.” Jenna unzipped her Bible and turned to an underlined passage. “‘A man can only come to the Father through Me,’” she read, then closed the book. “Without Jesus, they’re just soulless bodies. They’re killing machines. They are not fierce warriors.”

“What about the part that says love thy neighbor as thyself?” I asked. “That part’s in there too, isn’t it?”

We’d had this same conversation for a year, but I was too polite to shut her off. The requirement to be polite had been drilled into me since I was a kid. It would make people feel bad, my mother said, to show up their ignorance. We had to worry about making people feel bad, because we were Warrens. According to the laws of a dominant male progenitor, I’m a Bineki, but you wouldn’t know it to be around my mother, who insisted that we hyphenate our name. Warren-Bineki. The Bineki part could be lopped off if anyone important noticed it. My dad was like a stud the Warrens brought in to pep up the stagnant gene pool, then see-ya-later. Mother never talked about the Binekis, because they were ordinary. My mother was scared of ordinary people, a fear she learned from her grandfather, who was insane on the subjects of socialism, communism, and labor unions. He never stopped warning his family about the violence of the ordinary ignorant man. Ignorant people, my mother said, were unapologetically violent.

I disagreed with my mother regarding almost everything, but in this instance I had to admit she was right. In April, Jenna, who was uncommonly ignorant, had accused Barzai Marwat, the Pashtun who worked in the Admin tent, of inappropriately touching her while she was laying a Jesus trap for his Muslim soul. When she complained, our commander, Captain Whynnot, handed Barzai back to the Afghani warlord who owned him, and within twenty-four hours he was hanging on the town soccer field as an example. After I grilled her later, Jenna admitted the inappropriate touching consisted of the Pashtun’s pulling a strand of her frizzy red hair through his fingers and laughing—he had never seen anything like it. That was it. He touched Jenna’s spectacularly ugly orange hair. For that, Barzai died. After it happened, I asked Jenna if she felt remorse about Barzai’s execution; she said if he accepted Jesus into his heart before he died, he could apologize to her in heaven for touching her.

I thought Jenna was lost in her holy thoughts when she said, “I was kind of open, sexually, like you, before I found Jesus. So I don’t regret any of it. It was His way of finding me, I guess.” She leaned in as if we were intimates. “He’s looking for you, Kat.”

“Sexually open? Are you insane? Duck’s my boyfriend. Everyone knows that.” I’m not bragging, but I am very sexy-looking and people—people who either want me or want to look like me—think I’m easy. I’m not. I’m one of those people other people use like a blank page for their fantasies.

Jenna opened her Bible angrily. She was jealous that I had a boyfriend and she didn’t. After the Barzai incident most of the guys were overly polite to her, but that’s it. They weren’t taking any chances.

Anyway, it was ridiculous to think of Jenna as being sexually open. The entire time we were in Afghanistan, she never took off her long underwear. I don’t think she got naked even to shower. I imagined she had three nipples or some other deformity. There was an otherwise perfectly normal girl in Basic Training who had an extra nipple underneath her left breast. She showed it off, as if it gave her extra sexual cachet. Of course, Jenna would see it as the mark of the Beast or something.

I got up from my seat, banged my head on the overhead, and wiggled over Jenna into the aisle.

“Hand me my backpack, will you?” I saw an empty seat farther up the plane. “I want to get some sleep.”

Most of the soldiers were sleeping, their bodies contorted in positions any normal person would find crippling. I found out in Basic Training that if I wanted to sleep I couldn’t always wait for a bed with sheets. Being able to fall asleep standing up was the most useful thing I learned on active duty.

I squeezed into an empty window seat a minute before we were cleared for takeoff, and in a while we were above the storm clouds, the snowy peaks of the Hindu Kush looming in the distance. I had to start thinking of Afghanistan as “there” instead of “here,” and I willed my internal compass to shift as the plane climbed higher, separating me from Afghanistan. I tried to sleep, but the agitation of the soldier sitting across the aisle from me, obviously having a bad dream, kept me awake. When he let out a scream I got up, worked my way to the back of the plane, where Camacho, Reuber, and Duck were playing poker, and plopped into a seat behind them.

Camacho and Reuber lived on the same street in Warrenside. They were inseparable best friends the entire time they were in Kandahar until the last few weeks, when they were always fighting, as if to settle who owned that street before they returned. Talk about a booby prize.

They both had contracts in their duffels for three thousand dollars a month from the recruiter for Charon Corp, the private contractor that had a lock on independent enterprises in Kandahar, such as the laundry, food concessions, road construction, and private security guards. Three thousand dollars a month was an unheard-of amount of money in Warrenside. My family had seen to that. Three thousand dollars a month would solve all their problems, they thought. Poor people always think that money is going to solve their problems, that happiness rides into town on a pile of greenbacks.

Camacho and Reuber were smoking the Cuban cigars and drinking the twelve-year-old Jim Beam that the Charon recruiter had stuffed in their duffel bags for the ride home. They were drunk and seemed to be enjoying the sensation, for the first time in their lives, of having a high-rolling suitor validate their worth.

Duck came over and leaned against my seat. “You okay, babe?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “I had to get away from Jenna.”

“You think about what we discussed last night?” he asked.

What we’d discussed last night was that we should move out of our parents’ homes and get married. We had known each other since we were six, Duck pointed out needlessly, as if knowing each other forever was a giant plus. Duck had always assumed we would get married, and I couldn’t think of a good reason why we shouldn’t, except for this irritable voice inside of me that kept whispering, This is it? No more? I pictured a vault door slamming shut while I practiced shallow breathing to ration the oxygen that had to last the rest of my life. Airtight safe.

A part of me wanted to risk my safe haven to see what else was out there, but I was afraid—of what, I couldn’t say. And Duck assured me that rumors of an exciting life outside our bunker only meant that it was full of peril. People leave you, he said. People let you down. Sometimes I imagined that I could experience the world while safely married to Duck, but when I was with Duck, the only experience I had was…Duck. When I joined the Guard to escape my mother before I became infected with whatever infected her, Duck joined the next day, shuttering his thriving cabinet shop in Warrenside. He wanted to make sure I was all right. Protect his investment. I didn’t speak to him for three weeks after that, because, after all, Duck was one of the things I wanted to get away from. But I couldn’t stay mad. Duck is Duck.

He’d said last night we weren’t going to find anyone better. We were only in our twenties and we weren’t going to find anyone better? Maybe he was right. The men my mother found to distract me from Duck were like aliens. Once, I came home from high school and there was a boy, Jason, from Massachusetts with his mother in our living room. They were having drinks as if driving six hours to have a vodka martini in Pennsylvania was a normal thing to do. Our great-great-great-great-grandfathers came over on the same boat from England, which my mother thought gave us something in common but which would make them, I told her—after I drove Jason off with my boorish behavior—fellow religious misfits, and probably fourth cousins. Hadn’t there been enough inbreeding? I asked her.

My mother told me they were the richest family in Marble-head, Massachusetts. They made their money in textiles, although the factories had been sold decades ago and they were now living on dividends from bank stocks, et cetera. When I asked Jason what he wanted to do after college, he looked at me like I was crazy. Part of me was being mean, but part of me really wanted to know, because I was going to have the same problem. I would never have to work. Thanks to my mother’s indiscretion in marrying my father, we weren’t rich-rich—like my second cousin Alix Warren, who once hired a mariachi band on the spur of the moment for a week-long party—but we were rich enough that, if I was prudent, I would never have to do an honest day’s work. I would have just enough money to paralyze me. If you have a burning desire to do something—like if you know you just have to make movies or you have to draw apples or think about Aristotle—then not having to do anything else is probably a great thing. But most people aren’t like that. Most people have to dream up ways to get money, and that ends up being their life, and then they claim it was what they wanted to do all along and they find ways to be happy about it. Which isn’t a bad thing, it’s just ordinary.

I always wanted to experience exotic cultures. I pictured myself a reincarnated Michael Rockefeller, going into unexplored territories like New Guinea—not getting eaten by the natives like he did, of course—but when I actually found myself in an exotic place, Afghanistan, aside from a few forays with armed male escorts to the local Saturday bazaar that was just outside the gate, I was required to stay within the barbed-wire perimeters of the post and go to parties at the mess hall for made-up events and drink the spiked Gatorade just like all the other soldiers. I had all this interest in the Afghani people, but I wasn’t even allowed to talk to them. I would have very much liked to hear what they had to say about me, although I can see now that as far as they were concerned I was just one more thing that crashed uninvited into their lives, something that would eventually go away.

What I respected about Duck then was that he was unapologetically ordinary. He was a rock. He had a normal carpentry business and a normal guy’s enthusiasm for hunting, fishing, and paying his bills on time, which was a big point of honor with him. Men liked him because he did things well. Women wanted to marry him, because they interpreted his reserve as self-possession, and they were jealous of me and thought I was a bitch because I was stringing him along. Did their jealousy arouse my passion? No. Of course I loved Duck, but I didn’t feel passion, which I thought was like you had to be with that person or you would kill yourself, like Romeo and Juliet.

With Duck I never felt that desperation. But wasn’t that a good thing? I had enough tumult in my life with my mother’s instability that I thought one more tumultuous thing would probably unseat me. I tried, stupidly, to talk to her about Duck before I left for Afghanistan—should I marry him? et cetera—and she just said she’d read in an article in Redbook that what first attracted you to a person was the thing you would cite in divorce court as the reason you could no longer stand him. Look at me and your father, she said, our attraction was purely lust. And now she couldn’t stand for him to touch her. That’s when I lost it. Dad was great and she was lucky to have found someone to put up with her! I yelled and screamed and kicked her heirloom loveseat and knocked out one of the legs. The whole ugly sofa just kind of collapsed in slow motion with dust from about a thousand years ago rising up, making us both choke. You would have thought I kicked her, she got so hysterical. “That was to be yours!” she kept screaming, as if I had my eye on it, which I certainly did not. See, that’s what you do when you have money and you don’t have a job: you read magazines written for women who don’t have a clue how to live their lives. And then she said, I forbid you to marry Duck.

Forbid! I stormed out of the house and got my bike, which I ride when I’m pissed off, out of the garage, and pedaled wildly across the Harlan Gardiner Bridge to the south side of town and got a flat tire on a piece of glass in front of the army recruiting station. The staff sergeant who came outside to see what all the swearing was about told me he’d fix the tire while I relaxed and watched a DVD about women in the army. In this film the women were fixing planes, flying planes, and shooting other people’s planes out of the sky. “That looks so cool,” I’d said to the staff sergeant, totally buying into the probability that I was a woman warrior, and he looked me right in the eye and said, “You have no idea how cool.”

I reached out and squeezed Duck’s hand. “Let’s talk about it later, after we land.”

“I don’t know what we’re waiting for.”

“Duck, you in or out?” Reuber shouted over the seat.

“Fold. I’m out. I’m saving my money.” Of course. He was saving his money for our future. That’s exactly what he would do. He would make a list to facilitate our future together and check off each item until we achieved, relentlessly and inevitably, domestic bliss. He looked so happy with himself that I felt guilty for being the lone woman on the planet who couldn’t seem to appreciate a man who wanted more than anything to take care of her. I was honest with Duck. I told him I didn’t feel romantic about him, but Duck said romance was for children, that romantic love had a life as brief as a two-hour movie. But don’t you love me? he’d asked. I know you love me. And I said, honestly, I would be lost without you, and he said, Then we got lucky. What the hell else do you want?

Now he touched the lapis lazuli that Max had retied around my neck. “Come on. Let’s watch these guys play.” And he dragged me into the seat opposite Reuber and Camacho.

“It’s you and me, pard,” Reuber said loudly to Camacho. “Mano a mano.” He flicked his cigar like a gangsta and turned to me and laughed nervously. Reuber was a chronic gambler. He bet on sporting events, dogfights the Afghanis staged outside the wire, anything and everything that had an uncertain outcome. A couple of years ago he gambled and lost on Linda Pasko, a rerecovering coke addict he’d met when he’d wandered into a Narcotics Anonymous meeting in the church basement while waiting for his Gamblers Anonymous meeting to begin. He’d married Linda when the 501st was activated, and her picture, along with the picture of their kid (who he wasn’t allowed to see) was now in another—luckier—soldier’s duffel bag. No one in the 501st liked to be around him, because there is a superstition in the military that bad luck is contagious, but everyone loved to gamble with him because he could be relied on to lose all his money.

“You wanna go mano a mano, pato?” Camacho said. “Let’s just cut cards.”

“Temper, temper, Camacho.” Reuber laughed.

“A thousand bucks a cut,” Camacho said. “Cut the cards, pato.”

Reuber fanned the deck out in front of him. He studied the arc of cards. He looked at our faces: Duck had straightened up to watch; Camacho was staring at him coldly. He checked to make sure I was watching too, then laughed loudly, closed his eyes, and with his index finger pulled a card out of the line. He waved his hand over it like a magician and turned it over. A five of hearts. He groaned.

Camacho reached out quickly, picked up a card, and turned it over. A three of clubs.

Reuber jumped up and did a little dance, his hands clasped above his head. “Yip yip yip,” he crowed. “Wanna go again, pard?” he said.

“Fuck!” Camacho screamed. He fanned in the cards and tossed them on the floor.

“Pick them up!” Reuber commanded.

“You pick them up, asshole.” Camacho stepped up to Reuber, bumped him with his chest, and shoved him into the empty seat.

“Pay up!” Reuber shouted. He stood up and pulled a Nepalese kukri knife he’d bought as a souvenir out of an ankle holster.

“You gonna use that thing on me, maricón? You’d better be good,” Camacho said.

Soldiers had spilled into the aisles and were jostling for positions to watch. Duck stepped between them.

“I don’t think I’ve ever known two bigger assholes,” he said. “Did either of you ignorant fucks even read your contracts? You don’t see a penny of the money until your sorry asses deplane in Baghdad. Then the money gets deposited into your bank accounts, which I’m sure neither of you even have.”

They looked stunned; then Camacho laughed. “Sorry, pato.”

“You cheated me, you fucker. I’ll kill you!” Reuber screamed.

“Hey,” Duck said. “You guys want to get Article 15s when you’re a couple days away from being done with this shit? What idiots.” He pointed at the knife. “Give me that,” he said.

“It’s personal property. I paid for it myself.”

“It’s not yours anymore. Handle first,” he said. Then he settled them down in separate seats like a father separating his squabbling children.

Watching Camacho and Reuber fight upset me, because it was a reminder of what was waiting for all of us back home. How could you be gone from your life for a year and not expect the seams to tear when you tried to squeeze back in? Personally, I would have been glad for the year I was able to defer my life, but really, my life—Duck Wolinsky—was right there, looking at me to see if I approved of how he’d handled those two delinquents.