The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Tupac Shakur

Tupac Shakur is chain-smoking, sitting in a chair, when I arrive for our interview one December afternoon in 1995. Glancing out the window of his hotel room off the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles, he bears little likeness to the hotheaded, fire-breathing hellion that he often becomes in his videos, in the courtroom, or on the local news. With the television blaring in the background, the twenty-four-year-old rapper's eyes dart around the room as the phone rings, his pager vibrates, and room service arrives in unison.

For all his bravado, Tupac Shakur could easily be confused with a nervous wreck of a man. He fiddles restlessly with his hands (his fingernails are bitten to the quick), can barely sit still, and speaks at warp speed, hardly taking a breath. "I just wanted to get out and go back to doing what I was meant to do, which is music," he told me that day. "I've been working nonstop because I had nothing but time, you know, to think about all the things I wanted to say on wax. You don't know what it's like to not be able to do what you want, when you want. I had that for nine months. . . . I'm making up for lost time."

Even though we've met a number of times before, he sizes me up like I'm unfamiliar. I understand. Our previous interviews all occurred at a much calmer time in his life, when Tupac Shakur was a happier man. I'd met a lot of Tupacs over the five years I covered him. All were complex, all were thoughtful, and all were exhaustingly contradictory.

The last time we'd spoken at any length was shortly after he'd been released from prison, where he'd spent nine months for sexual assault. Here was the world-weary version of Tupac, the one who felt he'd been betrayed by some of his closest friends and couldn't or wouldn't trust anyone again. Given his circumstances during the previous twelve months, I couldn't very well blame him. But the sight of him that day caused me to recall the first time I'd met him, as a fresh-faced, ready-to-tackle-the-world, aspiring movie star.

It was at the wrap party for the film Juice in New York City. Tupac had the starring role of Bishop, an unstable high school kid who wound up on a killing spree. His performance was haunting and amazing, and he completely upstaged the other actors in the film. I was invited to the party for background on the story I was doing on the director, Ernest Dickerson, for the Los Angeles Times. Though I vaguely remembered Tupac from his appearances in the Digital Underground music videos, the videos did him little justice. In person he was breathtaking. With his never-ending, curly eyelashes, smooth mahogany skin, and a smile that could reach the high heavens, Tupac's star potential was unquestionable.

We shook hands briefly as the publicist explained I'd be interviewing him the next day about his director. Over eggs and ham the next morning, we talked for hours about our favorite films. To my surprise, Ordinary People and Terms of Endearment were two films the then barely twenty-year-old knew well and liked. If you've seen these movies, you know they are two of the whitest, middle-of-America films you'll ever see on the big screen. Not a black person in sight for the entire two hours. But I loved them, and so did 'Pac. He broke down the plot lines of each (along with exact quotes) and why they touched him so much. I hadn't been covering hip-hop for long, but I knew this wasn't the normal exchange a rapper had with a reporter. He spoke excitedly about Shakespeare and other literary works that had influenced him when he was growing up. Catcher in the Rye and To Kill a Mockingbird were at the top of his list.

He also explained why he saw his music as an outlet for his political beliefs. Given his pedigree as the son of a Black Panther, it was only fitting that he would have a well-thought-out worldview. Still, the charm was all his own. Over the next few years, I'd run into him at various outings: parties for the show In Living Color, a Mary J. Blige concert, and sometimes even at the mall with a ton of friends, laughing it up as they bought jewelry and baggy jeans. Yet what I was seeing differed from what I was hearing about Tupac getting into fights with the who's who of black Hollywood. I heard the news of him being shot in a New York City recording studio elevator a few months after I started at Newsweek.

Whereas two or three years previously I would have been surprised to hear about the rapper being the victim of bodily harm, the ever-changing Tupac had begun to take on a disturbing persona with his increasing wealth and fame. Most know the story of Tupac; he is indeed a legend at this point. However, it bears repeating that his childhood was a very complicated one.

Born to the Black Panther Afeni Shakur in June 1971, one month after she was acquitted on bombing charges, Tupac lived a somewhat nomadic life. His family shuffled between Harlem and the Bronx, and eventually landed in Baltimore. There he fell in love with all things cultural and entered the Baltimore School for the Arts, where he took acting and ballet. The family moved to Oakland, California, when he was in his early teens. He would later say this time was the beginning of a downward turn for him as he watched his mother start to use drugs and eventually moved out of the house to avoid seeing her waste away. He ended up on the streets selling crack to earn money, later hooking up with the rap group Digital Underground, working as their roadie. With time, his voice came to be heard on their records and his image featured in their music videos.

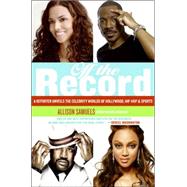

Off the Record

Excerpted from Off the Record: A Reporter Lifts the Velvet Rope on Hollywood, Hip-Hop, and Sports by Allison Samuels

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.