|

1 | (17) | |||

|

18 | (25) | |||

|

43 | (22) | |||

|

65 | (12) | |||

|

77 | (9) | |||

|

86 | (19) | |||

|

105 | (17) | |||

|

122 | (17) | |||

|

139 | (10) | |||

|

149 | (17) | |||

|

166 |

|

1 | (17) | |||

|

18 | (25) | |||

|

43 | (22) | |||

|

65 | (12) | |||

|

77 | (9) | |||

|

86 | (19) | |||

|

105 | (17) | |||

|

122 | (17) | |||

|

139 | (10) | |||

|

149 | (17) | |||

|

166 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Disappearances

I grew up on the mild-green, short-tufted buffalo grass prairies of northwestern Kansas. The High Plains they are called, and my family's spot upon them was Highland Farm. We were lifted on that great plain, four thousand feet above sea level, exposed to the sky, not cradled and protected by the earth the way Iowa or Minnesota farm families are. Each family in rural Kansas was alone together on the flat. At night we had distant yellow lights to remind us that we did have neighbors, but when those blinked off at bedtime, only the moon and stars penetrated the dark. Coyotes howled in our front yard.

When the Thanksgiving season approaches, I think of that home place and our big corner of Kansas more intensely than at other times, though, to tell the truth, it is on my mind always. Our rock-hard farmyard, gnarly with implement tracks and bony bumps, is the ground I walk on still, the given against which the baseline of my city life is too many eons removed. Here in town, the earth suffocates beneath pavement. Reality seems smoothed over, and I feel as if I'm the only one who isn't fooled. Beneath sidewalks and somehow beyond my neighbors' shiny cars and their meticulously raked yards, and then at whichever friend's house my son and I dine this year, a wintry defiance lurks, reminding me that except for that one savory hour when we eat, this holiday is a heart beating out into nothingness.

Thanksgiving, that day when we feasted on the bounty of our work, was often a forlorn holiday in Kansas. The hour at table was joyous, but the season itself boded emptiness and decline. This was especially true when we traveled. I have visions of desolate blacktops, straight and narrow between flat fields of stubble. The destinations were always towns where widowed great-aunts lived, their nondescript Plymouths parked in the unpaved drives of their trailer houses. Wandering the foreign burg with a remote cousin, I would try to imagine glamour in the unfamiliar surroundings despite streets of inelegant frozen mud. The movie theater, if there was one, would be shuttered, and the only traffic would be a sedate dirty pickup, jiggling slowly over the ruts as a farmer, with his belly full of food and relatives, headed out to a pasture to check his livestock.

The high point of those Thanksgivings came for me once when my brother Clark, home from his first teaching job in the far-off, eastern part of the state, let me drive his black GTO the entire hundred miles from our farm to Aunt Rosie's. I aimed the car with earnest precision, filling with pride as Clark complimented me. "Wow! You're a natural!"

I stared at my brother for as long as my fear of going off the road would allow. "You're just saying that, aren't you?"

"No! I mean it. If I didn't know better, I'd think you'd been driving since you were ten."

My brothers were that age when they started driving the pickup around the farm, but now Dad told me I would have to wait until there was a "teen" in my age, which wouldn't be until the following May.

Clark had graduated high school when I was only nine. He came home less and less frequently as the years passed, his departure merely the first of many disappearances I would witness. Thirty years later, he would be killed in a bicycling accident on Highway One, in California. "So far afield," I wrote in a memorial piece a year or so after the funeral, and my mother, who tends to hold her emotions close, confessed that those words caused her to set the article down and cry. We kids always took it for granted that to leave Kansas was a good thing.

Thanksgivings at home were more fun, although the guests delayed their arrival to the last anguished minute. The smell of roasting turkey reached into the farthest corners of the house, and my brother Bruce, five years my elder, became bored enough to play with me. He would challenge me to a contest I was sure to lose, such as seeing how far we could skate in our stockinged feet down the planks in the fake wood grain linoleum our mother had waxed the day before. Promptly yelled at, we would then loll in the easy chairs beside the windows at the far end of the big dining room. I would try to concentrate on a book, but my hair caught electricity from the vinyl recliner, and a menacing ionic charge hovered between Bruce and me as well. I could tell when his boredom was about to erupt in scathing sarcasm. The only potential victim in the vicinity, I would flee out into the frost-killed forest of my mother's yard. I bounced a stick along the sidewalk, stooped to cuddle a cat or dog, or went down to the barn to stroke the neck of Queenie, my ill-tempered mare. Sparks and dust would shoot up from her roan coat, thick for winter, causing her to lay her ears back and turn her rump on me. I would wander the back lot near the windbreak and climb around on ancient combines and in rusted truck cabs until finally I heard cars pulling into the yard.

The day was transformed. My girl cousins and I would dart back and forth among our aunts and uncles, swiping all the olives and sweet pickles off the relish tray. After the meal, we would tiptoe behind the barn and slide the door shut before Queenie made a dash for it. I would jam the cold bit into her mouth, then lead her out the front door and over to the abandoned concrete stock tank, where each cousin would perch in turn. After many attempts, we usually managed to get Queenie positioned right and steadied long enough for all to get aboard. We would ride out beyond the windbreak. Once, when a pheasant squawked and burst from the stubble, Queenie saw her chance and shied. My cousins and I, still holding onto one another, flew off. I clung to the reins, which jerked us around in an are and thudded us to the ground beneath the mare's front feet. Bruised in that exploit, we all four grabbed shovels and went to work on the anthill out by the storm cellar. We dug out of scientific interest in hibernation, we explained to our parents, but really it was out of a will to wreak vengeance on the animal kingdom, no matter how far down the ladder we had to stoop.

Even though I grew drunk with companionship on those rare Thanksgiving afternoons, dark would fall inevitably and the cousins would leave. The next morning the long weekend would begin. A thousand ewes chomped ensilage in the corrals, but the place seemed empty to me.

Our way of life was dying. I sensed this even then. Only old people lived in the fifty houses in my great-aunts' towns. Nearer home, a crop of widows and divorcees--my parents' sisters--began migrating, with my cousins, to Colorado cities. My brother Bruce and I departed as Clark had done, when we graduated high school. Today only my father and one of his Colorado-dwelling sisters still own farms. No one in my generation works the land. Some of us have tried our hands at farming, but generally only when other options have fallen through. I, for instance, went back to the farm at thirty-five, pregnant, and broke after a failed marriage. The return was humiliating, but soon the Kansas elements reclaimed me. Having been reared in the harsh environment, I hadn't felt truly alive since I last battled dirt and wind. That first spring, I rejoiced in the texture of the earth behind the plow. In the shop, armed with a grease gun, I scooted on a dolly beneath tractors, soothed by the smell of dust and grease, and by the massive machinery.

I reveled in its power. Ancestors only a couple generations before me had made their tenuous claim on the prairie, and now we were thundering over it in tractors bigger than their houses. But there were fewer of us. My parents, like so many farmers, had moved to town many years before, trading the farm I had grown up on for land closer to their other holdings. Children had spilled out of my grandparents' sod shanties; now I was living alone on this other ground, in a two-story, four-bedroom house with one baby boy. My parents thought I was crazy to want to live, as Mom said, "out in the middle of nowhere like that, in that ramshackle house." Dad commuted to this farm as if it were a factory, the land suited only for the mass production of crops, no longer a place to live.

The prairie of my childhood, with its cloud-shadowed rises and mild ravines, had disappeared. Instead of buffalo grass, rows of irrigated corn and soybeans vee-d into the distances. The state's floral pride, the sunflower, wasn't prominent along roadsides anymore, where only the toughest grasses survived the many poisons. When I walked through ditches on my way from the pickup to a waiting tractor, no grasshoppers clacked aloft to startle me. As a child, I had grown oblivious to their landings on my breastbone. The snake population had diminished as well, making such treks across ditches less foolhardy, but I missed the edge of adventure in the landscape.

Denuded of snakes and cousins, of friends, life in Kansas was even lonelier than in childhood. After two years, I began to make plans for my second migration.

The last Thanksgiving dinner I had in Kansas was at my parents' house. My son Jake and I were the only guests. My brother Bruce, although he was writing for a newspaper in another Kansas town, had taken his family to Arkansas to see his wife's parents. Clark was teaching chemistry at a junior college in Chico, California, too far to travel for a brief visit. There were no aunts and uncles around anymore. My mother and I went through the motions--stuffed the turkey, baked the pies, even got out the good china. But after we had loaded the dishwasher, put the tinfoil over the turkey and packaged up my share of leftovers, Mom went off to join Dad for a nap, and I, glad to have the event over with, plunked Jake into his car seat and started back to the farm.

The southerly sun cast angled light over miles of stubble--wheat, corn, and sorghum. Harvest had been laid up in the fat corrugated grain bins on the farms, and the sun made the elevators--twin white towers in every town--glisten. Jake fell asleep, and once home, I carried him inside and laid him in his crib. The house was silent, grown dingy in our absence. To offset the loneliness, I sat down in the kitchen and ate another piece of pecan pie. Then, stuffed beyond belief, I pulled on my farmer's flannel-lined denim jacket and went outside into the falling evening to walk. I followed the ruts the combine and trucks had torn through the yard after an early snow, which had frustrated our corn harvest. The shop's wide doorway gaped black and quiet where the day before my father's hammer had clanged, realigning a bent sweep rod beneath the flame of his acetylene torch.

I strolled among the grain bins, some squat, some tall, all of them full. At the bases of their doors lay mounds of grain that had escaped through the cracks. When I came to the largest bin, I stretched out my arms to embrace it and lay my cheek against the cold tin hillocks. Back in July I had waded this wheat in the beds of trucks, holding my scoop out to direct its flow from the combine augers. Yet in the harvest rush, I'd forgotten to capture a bag full before we dusted the crop with Malathion and binned it. Beneath the metal lay twenty thousand bushels of wheat, and Mom had baked her Thanksgiving bread with white flour from the store. With winter coming and Jake asleep in the quiet house, all that bounty seemed sterile and useless, the future hollow. I asked myself the question my father has obsessed on ever since his boys left for other occupations: Who will carry on?

Julene and her son Jake, he came to think during the two years we lived there. I relished my stature in the wake of my brothers' defections. I wanted Jake and me to be his answer, but had come, finally, to the disappointing conclusion that we were not.

Today, I live eight hundred miles from western Kansas, too far to travel for brief holiday breaks, but I've returned for the past four summers. I want my son to know his grandparents and their land. I can't uproot myself completely, nor reconcile myself to the fact that the land, once lost to me, then briefly reclaimed, is not our future.

Summers are always a busy time in Kansas, as long as it hasn't hailed or come a severe drought. Wheat trucks barrel down the gravel roads in July, hauling their bounty to the elevators, then, rattling empty, careen back to the fields, where the combines graze like giant mantises. I like to see the wheat before the machines pull in, a county full of it. I like to walk in it when it is unscathed and trackless, its trillions of bristles whispering. The effect is delusory, as if the occurrence of so much grain in one place is a natural phenomenon, and walking in it, I am in communion with a natural element, as ubiquitous as air or water or heat.

It was on a day like that a couple summers ago, when the buds were burnished gold but the stalks still too green to cut, that I decided to pay a visit to the home place. The road carried me out there, past both abandoned and still vital farmsteads, where green combines and red and white trucks waited silent and ready, the sun glinting off their windshields. On the sole curve, past the Rickard place, I felt the excitement in my belly from when I was a kid driving home from high school and would take the turn too fast. I drove with my windows down, the air rushing in, fire-lapped and dry. Fifteen miles of that, the tires rumbling over gravel, an occasional rock dinging the tailpipe, and then there it was, still five miles away, but prominently visible because of the gentle rise on which it stood. The Carlson farmstead was my family's center of gravity, but others could drive right by it, not even feeling the magnet's pull in their stomachs, as someone in a wheat truck did just then, filling the car with dust. I swerved and re-fastened my attention to the road until I arrived at the turn onto the half-mile of dirt track. After a dip between what used to be two pastures, but were now wheat fields, the trail dead-ended in our old farmyard.

I parked below the knoll leading up to the house. Opening the car door onto what I expected to be mere heat and wind, I was startled by a deer with a huge crest of antlers. It tore out of the thicket that had once been our north yard, where Dad had braced up the cherry tree with a makeshift post and rail crutch, and leapt past the remnants of the sheep barn into the wheat field. The pasture beyond that long building had once seemed to reach into eternity, but was now reduced to a single circle of wheat beneath the breadth of a pivot sprinkler. I watched the deer bound through the wheat like a merry-go-round animal, his rack aligned in the crosshairs of the vacant afternoon, then turned back to the house yard.

Some of my mother's yellow rosebushes were in bloom, and I imagined her posing before them, as she had for one of the pictures in the family photo album, the skirt of her housedress hugging her belly and thighs in the wind, which was always too intense and bothersome--full of dust in summer and needling cold in winter--to be called a breeze. I walked carefully, pulling back the branches that had overgrown the sidewalk, trying not to break or trample anything that would make the deer's haven less familiar when he returned. Millions of moments circled inside me, stirred by this visit as were the leaves overhead, tossed by the perennial wind. Should I tell Mom about the deer and the flowers, I wondered? She would be pleased to hear about them, but reminding her of the empty house would upset her. She never would have agreed to the trade, she once told me, had she known the farmstead her father built would wind up abandoned.

Grand by local standards, the old house is a monument to our dead: Grandpa Carlson, with his bald head, his Swedish accent and his way of turning big dreams into reality; Grandma Carlson with her nubbin bun, her sternness and her complaining; Uncle John, the farming hope of my mother's family, who was struck by lightning while driving a tractor; and now Clark, my older brother, who had died just the previous year. It was his death, so recent, that brought me to the home place that day.

Someone planted two evergreen trees after we moved. I had to lift their branches to make my way up the wide steps of the south porch. I ran my hand down the beveled glass in the front entry, then discovered the door unlocked. The house was as cold as a walk-in meat locker, holding the chill over from the night. Glass still lined the sashes of the bay windows, some of it original, rippled, hand-blown--a wonder, since the Carlsons, then the Bairs had raised children in the house, and at least two other families had lived in it since we left. I had forgotten how big the windows were. No easy chairs beckoned from in front of them, however, and the air conditioner had been removed from below the middle one, leaving a hole that framed a square patch of brush. Someone had torn the wall out between the dining room and Mom's sewing room. They laid a turquoise carpet over the wood grain linoleum Bruce and I had skated down. During my long absence, the house had been restored in my mind to its original elegance, so I was disappointed all over again by the north wall, which separated the dining room from the kitchen. Originally, a set of leaded glass cabinets and a mantel with a mirror above it appointed that wall, but, saying these features were too old to repair, my parents had them torn out the same year they had the upstairs balcony removed.

My mother had hung Clark's senior picture in the middle of the wall, when it was newly blank. As a child, I stared at the picture often and proudly, noticing how perfectly squared were his shoulders, the bows of his tie and his flattop. Remembering that picture's isolation reminded me of the time his classmates went on a field trip to Colorado Springs and Dad made Clark stay home to help with lambing season, and another time when he dressed up in the same gray suit he wore in the picture, to compete in a high school best-groomed contest. He wasn't able to get the grease out from under his fingernails, had even tried gas, and then reeked of the fumes. I remembered him standing in the dining room beside the varnished pine door leading onto the mud porch, where he'd scrubbed for nearly an hour. He let Mom perfect his tie knot, then said, his eyes brimming, "I look like a dumb farmer."

Upstairs, the hallway was still fifteen feet wide. Mom and Dad's room, gaping and bedless, no longer exuded mystery. Mom had always kept the curtains drawn over the windows, making it darker than the rest of the house. My cousins and I once got in trouble for sneaking into the room at night when the adults were gathered in the living room below. We tried on Mom's costume jewelry and wobbled in her heels before her big round dresser mirror.

Bruce's room had one window, looking west over the backyard. When as a child I entered his messy lair, through the narrow corridor walling off the stairwell, the afternoon light exploded through that window, and it seemed as if Bruce lived in the most spacious room of all. I now leaned my forehead against the filmy pane and looked down into the backyard. Concealed in the plum and olive thicket, I knew, was a concrete dome with a rusted vent pipe sticking up in the middle--the cap over the septic tank. To me as a child, it had been a mysterious surface on which to prance. There was no odor, just the bewitching contour of a spaceship. I would sit on it early evenings and watch the sky blaze over the elm windbreak beyond the hog lot. During fall sunsets, it was as if the yard's bare limbs were strewn with a giant canopy of rainbow satin. I would watch until I could barely distinguish the outline of the tall, ark-shaped hog feeder beyond the wire fence.

My mother told me that her older siblings had grown up in a sod house near the spot where the feeder now stood, but the roof had blown off and the blocks were crumbling by the time she was born. I would sit until she called me in to help serve supper at the big Formica dining table, where waited my father, two or three hired men, and my brothers, whose work among the men I envied.

I turned and leaned on my brother Bruce's sill. His room was bare now, like all the others, but had once contained two floor-to-ceiling stacks of cigar boxes filled with things I was afraid to sneak peeks at as a girl. I feared he may have tied an invisible thread between the dresser and his blue-painted chest of drawers or come up with some other devious detection system and would then repay me for the trespass. He collected arrowheads, animal teeth, sulfur for stink bombs, bullet casings, bird bones, bug carcasses, gunpowder gleaned from spent firecrackers, and chunks of molten glass he'd found in our dump, a bulldozed hole south of the house. He had slithered about the farmstead, making discoveries on his own ever since he was a toddler, sparking proud wonder in our parents, who were impressed by his curiosity and genius. And then I had come along, diverting some--but nowhere near enough, I had always felt--of their attention. I followed him everywhere in the manner of a younger sibling, trying to share in his discoveries, trying to win his admiration, while he fended me off with insults and made it clear he wished I would evaporate.

A different dynamic was at work between him and Clark. Bruce out-charmed his brother, whose temperament, as the eldest child, was serious, sensitive, and eager. While our father held Clark up to the First National Bank calendar and taught him his numbers when he was only three, then taught him to spell the word "International" by pointing out the letters on a wheat truck dashboard, Bruce engineered his own education. He found arrowheads on pasture hills, built a raft on which he attempted to float the Republican River (but wound up sinking), and subscribed to the Junior Audubon Society. He was the only one among us who knew there was no such thing as a chicken hawk. The hawks we referred to in that way were sometimes red-tails, sometimes ferruginous, he replied without hesitation when, a decade into adulthood, I developed my own interest in birds.

I crossed the hallway and paused for a moment before entering Clark's room. I wished there were some ritual by which I could make his ghost appear, some means to convince myself he still existed. The frequent dreams I had about him were not enough. I crossed the threshold and blew a kiss onto the air where his tin-framed bed used to be. During my early childhood, when Clark was a teenager, his room had radiated brains and accomplishment. His grand prize 4-H ribbons, for bottle calves, lambs and for test plots of wheat, had hung beside his Future Farmer of America and honor roll certificates. I walked to his window. He had stared out at the same baked gray farmyard as I had, with the big barn opposite and the dead cottonwood tree by the concrete stock tank where my cousins and I had mounted Queenie. The house stood at the center of Grandma Carlson's land, leased by our father, and when Clark got up mornings, he must have looked out to where his tractor waited for him in the nearest field. Behind it, a straight-edged line would have separated the dark dirt from the gray. He might have computed, on waking, as I did years later when I finally got my chance to farm, how many hours it would take him to finish the field. If he had any daylight left, he would use it to wash and polish his car, a red Ford Falcon. On Saturday nights, Dad let him fill it up from the farm gas tank, and he drove it to town, where, in the manner of kids all over the High Plains, he cruised Main Street in search of fellowship with his own kind.

(Continues...)

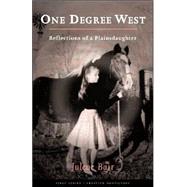

Excerpted from One Degree West by Julene Bair. Copyright © 2000 by Julene Bair. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.