| "Thou Shalt Not" | p. 1 |

| Before Orders | p. 3 |

| After the Summer of Love | p. 59 |

| Gay Is Good | p. 111 |

| Falling Apart | p. 129 |

| Secret's Out | p. 154 |

| Confrontation | p. 196 |

| Into the Courts | p. 250 |

| "Who Trespass Against Us" | p. 269 |

| The Globe and the Church | p. 271 |

| Explosion | p. 294 |

| The Unburdening | p. 322 |

| Inside, Outside | p. 353 |

| Outside, Inside | p. 411 |

| Toward Holy Cross | p. 455 |

| The Backlash | p. 511 |

| Faith and Morals | p. 548 |

| Postscript | p. 589 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 595 |

| Notes | p. 599 |

| Bibliography | p. 635 |

| Index | p. 639 |

| Table of Contents provided by Blackwell. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

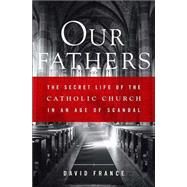

Excerpted from Our Fathers: The Secret Life of the Catholic Church in an Age of Scandal by David France

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.