CONTENTS

FOREWORD

INTRODUCTION

BASIC PASTRY INGREDIENTS

WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

Crusts

Fruit Pies

Chiffon Pies

Meringue Pies and Tarts

Custard Pies and Tarts

Ice Cream Pies and Ice Creams

Tarts and Tartlets

Savory Tarts and Pies -- and Quiche

Biscuits and Scones

Fillo

Strudel

Puff Pastry and Croissant

Danish Pastry

Brioche

Cream Puff Pastry

Fillings and Toppings

Sauces and Glazes

Techniques

Ingredients

Equipment

SOURCES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INDEX

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

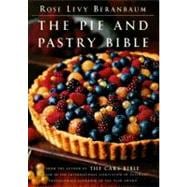

I have been thinking of this book asThe Pastry Biblefor ten years now, since the publication ofThe Cake Bible.But after much discussion, I decided to give it the titleThe Pie and Pastry Biblebecause I discovered that most people do not know exactly what "pastry" means or that piesarealso pastry.

The Oxford dictionary defines pastry as: "Dough made of flour, fat and water, used for covering pies or holding filling."

The writer couldn't have known the pleasure of a fresh tart cherry pie or of a flaky, buttery croissant, or his definition would never have remained so dispassionately matter-of-fact.

I did not grow up with much of a pastry tradition. Neither my mother nor grandmother baked. Once in a while I was treated to either a bakery prune Danish or &233;clair but that was it. Sunday morning breakfast was a buttered bagel. My father, a cabinet maker, also provided the greater New York and New Jersey area bagel factories with wooden peels, and the fringe benefit was a weekly string of fresh bagels.

The first pie I ever attempted was cherry pie, using prepared pie filling. It was during Thanksgiving break of my freshman year at the University of Vermont. I had just learned the basic techniques of pie making in class and wanted to please and surprise my father. It turned out that everyone else in the family was surprised as well but in different and disagreeable ways! The oven in our city apartment had never been used except to store pots and pans. My mother, who was afraid of lighting an oven that had been dormant so long, made a long "fuse" from a paper towel and took me into the living room, covering her ears. A few minutes later, when the flame reached the escaping gas, there was the loud explosion she had anticipated (not to mention unnecessarily created). Minutes later, my grandmother (whose domain the kitchen actually was) came running in crying, "The soap, the soap!" It turned out she stored her bars of soap for dishwashing in the broiler under the oven. The soap, by then, was melted and bubbling (much to my amusement). But the worst surprise was yet to come. During the baking of the pie, the cherry juice started bubbling out of the pie and onto the floor of the oven where it started to burn and smoke. Apparently the steam vents I had carefully cut into the top crust had resealed from the thick juices of the sugared cherries.

At Christmas break I tried again, this time lighting the oven myself -- though I did forget to remove the soap again. My creative though absurd solution to the sealed vents was to insert little straws in them so that the juices could bubble up and down without spilling. Finally, I discovered that all that is necessary is to make little cutouts, which, unlike the slits, cannot reseal. But these days I prefer a lattice crust for my cherry pies. The fruit is simply too beautiful to hide.

My next attempt at pie was two years later as a new bride. I wanted to surprise my Vermont husband with a New England specialty he claimed to enjoy: pumpkin pie. As I was emptying the contents of the can into the pie shell, I licked my finger, which confirmed my suspicion that this was not a pie I was going to like. When I presented it for that evening's dessert, I couldn't resist adding: "I don't know how you can eat this; it tastes like a barnyard." To which he answered: "It does and I can't! What did you put in it?" "Pumpkin." I said, thinking what a ridiculously obvious question. "What else?" he asked. "What else goes in?" I queried. "Eggs, brown sugar, spices, vanilla," he enumerated as I sat there feeling like a total fool. Coincidentally, I was reading James Michener'sSayonara,in which the Japanese bride did the same thing, making her American husband a pumpkin pie using only canned pumpkin without sweetener or flavorings, thinking that it was pumpkin pie that somehow appealed to Western taste. It made me feel a lot better. (Too bad I hadn't reached that chapter before my own misadventure!) The next week I tried again, making it from scratch. To my surprise I loved it. It took me thirty years to achieve what I consider to be the state-of-the-art pumpkin pie.

Making pie crust and other pastries was another story. Pie crust, in particular, never came out the same way twice in a row. My goal in writing this book was to delve into the mysteries of pie crusts so that they would always come out the way I wanted them to be -- tender and flaky -- and if not, to understand why. My goal was also to convey this knowledge in a way that would encourage and enable others to do the same. This was far more of a challenge than cake baking. When it comes to cake, if one follows the rules, perfection is inevitable. But for pastry you must be somewhat of an interpretive artist as well as disciplined technician. You have to develop a sense of the dough: when it needs to be chilled or when it needs to be a little more moist. The best way to become proficient is by doing it often. And here's the motivation: The best pastry is made at home. This is because it can receive individual attention and optimal conditions. Try making a flaky pie crust in a 100°F. restaurant kitchen and I'm sure you'll agree. Also, there is nothing more empowering than the thrill of achieving good pastry. I'll always remember my first puff pastry. My housekeeper and I sat spellbound before the oven, watching it swell open and rise. It seemed alive. It was sheer magic. I also cherish the memory of my nephew Alexander unmolding his first tartlet when he was a little boy (and didn't kiss girls). The dough had taken on the attractive design of the fluted mold and he was so thrilled he forgot the rules and kissed me!

Many people think of me as "the cake lady," but the truth is I am more a pastry person! I love cake, but I adore pastry because of its multiplicity of textures and prevalence of juicy, flavorful fruit. I have had the pleasure of developing the recipes in this book for more than ten years. All were enjoyable, but I have included only those I personally would want to have again and again.

My fondest wish is that everyone will know the goodness of making and eating wonderful pastry. Then they will walk down the street with a secret little smile on their faces -- like mine.

Rose Levy Beranbaum

Text copyright © 1998 by Cordon Rose, Inc.

FOREWORD

The first year I was married, I lived in Amherst, Massachusetts, and spent most of my time cooking my head off. I especially liked to make desserts -- the more complex, the better. I made Gâteau St.-Honoré, Zuppa Inglese, Napoleon, Dobos Torte every day of the week. No kidding. Word of my feats got out, and I was approached one day by another faculty wife at Amherst College (where my husband taught) who asked me to teach her how to make a pie crust. I was horrified. A pie crust? How in heaven's name would I ever teach anyone how to do something as elusive and as complicated as that?

Everything changed when I began to edit this book. Just as I had with Rose's book on cakes, I became mesmerized by pies. And since Rose is like Merlin in her ability to draw you in, it wasn't long before I became obsessed by pies. It took hold on a Sunday afternoon, as I left her apartment clutching a sliver of her pear pie. I saw as she sliced it how succulently juicy the pears were, yet there was no dripping of juice onto the pie plate -- all the juice seemed to cling to each slice of pear. I saw the crust as she was slicing it -- and it seemed crisp, crunchy, flaky -- and it was the most beautiful beige-brown against the juicy, holding-the-juice-to-themselves pears. When I got home and shared the treasure with my husband (reluctantly), I realized that Rose had transformed the meaning of pie for me.

I guess I'm bound to get some people angry when I say that I've always thought pies have needed Rose to lift them out of the homey, soggy, less-than-glamorous position they've occupied in America. The fact is, nobody knows how to make them well anymore. In her ingenious, utterly meticulous way, Rose has reflected long and hard on just how to bring a pie to the level of greatness. She has devised ways that enable a crust to stay crisp beneath the most juicy fruit filling, by placing the pie plate on the oven floor. She makes a fruit more succulent by macerating it with sugar, carefully collecting the juice, and cooking it so that it caramelizes and can create a synthesis with the fruit when the pie is baked in the oven. Rose makes the most of fruit, too. She keeps whenever and wherever possible much of the fruit in her pies fresh, so that it won't lose its personality when it reaches our mouths, and she cooks just enough of the fruit to provide a juicy cushion.

I could go on in this way about each one of Rose's recipes in this book, and I know everybody would think that I was writing a press release after a while. I'll try to be as composed as I can, but who else but Rose would go to Denmark and find out what Danish pastry is all about, and come back with recipes that make you swear you'll make Danish pastry as often as you can. Who else but Rose would go to Austria, and to Hungary, zealously watching master strudel-makers stretch dough, and then come home and make it one hundred times in her apartment in New York, so she could get it just right for us? Who else but Rose would come up with a cream cheese crust whose taste and texture defy description?

I used to think, before I edited Rose's first bible, that I made cakes as well as any home baker. Rose brought me to another level I didn't know existed. I began to make my cakes differently after that, and I also began to understand how important taste was to everything. I'll never add vanilla, or a strip of lemon zest, to a recipe again, whether it's one from Rose or not, unless it smells wonderful and is of the highest quality. I'll never make pound cake unless all the ingredients are at room temperature. With this book, I'll go to the farmer's market excited to find red currants, blueberries, Marionberries, sour cherries, and know with confidence that when I put them in one of Rose's crusts, they'll lose none of their fresh, lustrous brilliance. Now finally, after thirty-three years of baking, and under Rose's tutelage, am I ready to give the woman who asked me to teach her to make a pie, and roll a crust, the class she wanted.

Maria Guarnaschelli

Vice President and Senior Editor

Scribner

Text copyright © 1998 by Cordon Rose, Inc.

Excerpted from The Pie and Pastry Bible by Rose Levy Beranbaum

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.