Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

In the winter of 1949, when Joan and Mimi Baez were little girls, their aunt Tia moved in with them. She came through the chimney and brought music and ice cream in her carpetbag, or it seemed that way to them at the time.

Joan, who was eight, and Mimi, who was four, shared a bedroom on the second floor of the Baez family's clapboard house in Menlo Park, California, near Stanford University, where their father, Dr. Albert Baez, thirty-seven, worked in a cold war program to teach physics to military engineers in training. Their older sister, Pauline, ten, kept to herself in her own small room, a converted closet, and their mother, thirty-six, for whom Joan was named, tended to the house while listening to classical music on 78-rpm records a salesman picked out for her. The female contingent of the family submitted reluctantly to rooming-house life until the elder Joan's sister Tia, thirty-nine, joined them, freshly divorced for unimaginably adult reasons never to be discussed.

Sisterhood understitched the Baez household. The first of Joan and Albert's children had been named for Tia, whose proper name was Pauline Bridge Henderson (Tia meaning "aunt" in Spanish, Albert's native language), just as the third born had been named for their father's only sister, Margarita; Mimi was her middle name, which everybody in the family except Albert Baez preferred. Tia was fair and soft, with long, curly chestnut hair and the free-spirited poise of an artist's model; she somehow always seemed as if she would prefer to he nude and gazed upon. This may have come from experience: Tia had married a painter, traveled through Europe with him, studied dance with Martha Graham, written poetry ... she had, that is, lived all her era's romantic feminine dreams. Sipping sherry in the kitchen of the boarding house, Tia would regale her sister and the girls—sometimes all three, more often only Joan and Mimi, since Pauline tended to play alone—with stories of her travels and readings from her notebooks. To Big Joan, the relief, the novelty, and the vicarious pleasures that Tia provided nearly outweighed the envy she incited. A strong, handsome woman, the former Joan Bridge had married young and with ambivalence; feeling sinful and confused for having loved another woman, she yielded to the overtures of a gentle Mexican academic who said he would accept her as she was. In the decade to follow, she fixed her resources on rearing children. "You could feel the house lighten up when Tia came in," Mimi would recall. "But Tia was not a worker, and so Mother was real resentful that Tia's role was to come around and be the clown, get everyone laughing and basically not hold her end up. Mother carried buckets of stuff, and Tia told stories—and we loved her, because she liked to have fun, and she would tell us stories that seemed really naughty, and she went out on dates with men."

For several years, Tia kept company with a fellow living in the boardinghouse, Rugger, a bit of a roustabout with a child's sense of abandon that delighted the Baez girls. "He'd take my sister and Joanie and Mimi out together, and they'd have a glorious time," said Big Joan. "He'd buy them all kinds of candy and ice cream, and he'd take them to double features. He'd ruin them! Their father was furious—‘Why do they have to go to a double feature? Isn't one movie enough?’ I couldn't explain it to him. The girls were still girls—they were supposed to have fun. He was beside himself. He was terribly jealous, and so was I." Evidently picking up glimmers of information from snatches of grown-up talk, Joan and Mimi seemed troubled by the family conflict over Rugger. "The girls were very upset that the adults were at odds," Tia remembered. "They thought they were doing something wrong because they were happy, or Rugger and I were doing something wrong because we were in love and enjoying it. I was afraid they were getting the impression that men and sisters don't mix, and I guess they did. But Mimi and Joanie were fine, as long as they got the same kind of ice cream and the scoops were the same size."

As they grew, Joan and Mimi drew closer, and their older sister turned inward. "When Mimi was very young, Pauline and I hated her," Joan remembered. "Mimi was the youngest and the prettiest, so Pauline and I conspired against her. That didn't last long. Pauline was a loner." When she was eleven, Pauline built a tree house and spent much of her time between school and sleep alone there; when Joan asked if she could play with her, Pauline replied, "Sure, you can be the daddy. Go to work. Bye!" At mealtime Pauline would construct a barricade of cereal boxes around her place setting. "After Pauline built that tree house, she never really came out," said their mother. "Mimi and Joanie discovered each other. They were very different, like my sister and me in a way, but very tight, like us." Because young Joan could draw (mainly clever, skillful sketches of her family, her classmates, and herself), she was considered the artistic one. Joan also had a quick, sassy wit and a knack for imitating voices—"Joanie was so funny," said Mimi, "she made you laugh so hard you almost didn't mind that it was at your own expense." A lovely girl with deep liquid brown eyes and an easy, disarming smile, Joan thought of herself as unattractive; surgery to remove a benign tumor had left a tiny scar on her torso that she saw as monstrous. She endured schoolyard taunts because of her Mexican surname and dark skin, and she coveted her little sister's fairer, delicate beauty. "Mimi was the pretty one," said Dr. Baez. "She looked like an angel. All three of my girls, they all were beautiful—Pauline, Joan, too—beautiful. But not like Mimi." She had physical confidence and poise; under Tia's patronage, Mimi had been studying dance since the age of five. She struggled with books, however, because she was an undiagnosed dyslexic, and her schoolwork suffered. Mimi envied her sister Joan's way with words and her ease in adult company. "Joan was very jealous of Mimi's looks. It was very hard for Joan. Joan always thought she was ugly," said their mother. "I think Mimi was just as jealous of Joan ... [because] Joan was so talented. They were both talented, but I don't know ... I just know they loved each other so much, I thought sometimes they'd kill each other." The girls held hands constantly; once as they were walking, Mimi squeezed so tightly that her fingernails dug into her sister's palm, and blood smeared onto the sides of their dresses.

Encouraged by one of Albert's university friends, the Baez family started attending Quaker meetings, and they always brought the girls, all of whom endured the sessions dutifully and absorbed elements of the Quaker ideals that they understood and liked. "It was something we had to do, and it was a chore," Mimi would remember. "But all three of us seemed to get the basic idea that peace was a good thing. We basically made faces at each other [at the meetings]." Still, one speaker succeeded in capturing Joan's attention: a small, frail monkish fellow named Ira Sandperl. Moved by his lecture on pacifism, Joan asked him for advice in applying his principles to her life. "I asked him how I could learn to get along with my sister Mimi," Joan recalled. "She was very beautiful, and we fought all the time. It seemed so endless and unkind. Ira said to pretend that it was the last hour of her life, as, he pointed out, it might well be. So I tried out his plan. Mimi reacted strangely at first, the way anyone does when a blueprint is switched on him without his being consulted. I learned to look at her, and as a result, to see her for the first time. I began to love her."

All three girls showed interest in music. Pauline had taken some piano lessons and had practiced regularly but froze when it came to playing for her teacher. She and Joan (who had also studied piano briefly) both learned how to play the ukulele from a Stanford colleague of Albert Baez, Paul Kirkpatrick. "He taught Joanie and me the same thing on that ukulele the same day," remembered Pauline. "I became so concerned in doing my little three chords correctly, I didn't want anybody to hear me at all until I had it perfect. And Joanie picked up the thing and just started strumming away, and if the chords weren't quite right, it didn't matter—she played it for the people right off, you know. And then she just went on playing, because everybody clapped and cheered and said, ‘Oh, isn't it great!’ And me, I kept practicing my three little chords until they were perfect. I guess they didn't think I was very good, because they didn't even hear me. But it was like that. Joan was ‘Ta-da!’—center stage." During one of these living-room performances, Joan decided to sing, too. "Singing in the house while I played the ukulele—that was the first time I remember people saying, ‘Oh, you have a very nice voice,’" Joan recalled. Mimi scored high on a third-grade music aptitude test and took violin lessons for several years. "I did very well, but I was really more interested in singing," said Mimi. "But that was more of Joanie's thing."

Late in the spring of 1954, when Joan and Mimi were thirteen and nine, Tia and Rugger took them to a concert in the gym of Palo Alto High School. It was an informal program of songs and talk to raise funds for the California Democratic Party, featuring Pete Seeger. Tia considered herself politically aware and liberal, like Big Joan and Albert, and she wanted Joan and Mimi to hear Seeger. "I liked him very much," Tia said. "I thought if I still had some influence on those girls, they should hear something they weren't going to hear on the radio." Indeed, Seeger could not be found on any of the country's commercial stations, nor on records from the major labels, in concert halls, or in nightclubs; he had been blacklisted in 1952 for his association with Communism. Along with Woody Guthrie and Huddie "Leadbelly" Ledbetter and folklorist Alan Lomax, Seeger had been a central figure in the boomlet of folk-style recordings and performances between the Depression years and the beginning of the Second World War. By 1950 Seeger, as a member of the Weavers (along with singer-guitarist Fred Hellerman and singers Lee Hays and Ronnie Gilbert), had helped break folk into the pop mainstream with the quartet's hit records of "On Top of Old Smokey," "Wimoweh," and Leadbelly's composition "Goodnight, Irene," among others. The accomplishment carried irony for a socialist such as Seeger—a demonstration of his music's appeal to the masses through commercial means that brought sizable profits to the record industry, as well as to the Weavers. With the rise of the cold war and the intensification of anti-Communist sentiment in the early 1950s, Seeger found himself liberated from the irony of mass popularity and economic success; he was no longer welcome in most concert halls and nightclubs and returned to performing in community centers, schools, and private clubs for modest sums, usually under the auspices of organizations associated with the left. At Palo Alto High School, the political component of his presentation was one of implication. "It seemed to me that I could make a point if I made it gently," Seeger explained. "I suppose you could say what I was doing was a cultural guerrilla tactic. I sang songs about people from all walks of life, and I talked about how anyone from any walk of life could sing this kind of song himself. What I was getting at was the idea of flip-flopping the power structure, so every individual had some power, rather than all the power being centered on a few organizations or just one. I said, ‘Sing with me. Sing by yourself. Make your own music. Pick up a guitar, or just sing a cappella. We don't need professional singers. We don't need stars. You can sing. Join me now....’"

The idea surely ran counter to the prevailing cultural tenets of glamour and professionalism: Down with the aristocracy of the Hit Parade, up with egalitarian amateurism. A message with appeal to the disenfranchised, the disconnected, and the tone deaf alike, Seeger's call for musical insurgency touched both Joan and Mimi Baez, as it would connect with many other young people who saw him perform during the 1950s. "Joan told me later that it was after that concert that she looked herself in the mirror and said, ‘I can be a singer, too,’" Seeger recalled.

"I don't remember the actual concert anymore," Joan would say. "All I know is that was a major moment for me." (Mimi would not remember any of it.)

"I remember," said Tia. "Mimi and Joan both announced that they decided they wanted to sing. Mimi was not exactly a big out-there, out-in-front girl like Joan. But she really loved music. Pete's message was, you know, ‘That's okay. You don't have to be a star to sing. Sing for yourself—that's what matters.’

"Joan came away with something a little bit different ... ‘Wow, maybe you don't have to look like a movie queen, and you can still be a star. I can sing. So I can go up there like Pete Seeger, and everybody will like me.’

"And I thought, ‘Now, how different can two girls be and want to do the same thing?’"

Chapter Two

Seeger described himself as a sociopolitical Johnny Appleseed during the mid-1950s, "sowing the music of the people," and he would quickly have reason to claim more success than his metaphoric progenitor. At the end of the high school concert Joan and Mimi Baez attended, Seeger sold a copy of his home-published booklet How to Play the 5-String Banjo to Stanford sophomore Dave Guard; three years later, Guard and two friends, Nick Reynolds and Bob Shane, inspired by Seeger and the Weavers, formed a folk group and called it the Kingston Trio (to evoke the Jamaican township rendered voguish by Harry Belafonte and the calypso fad). A nearly groomed, collegiate, WASPy-looking group of athletic young men singing and playing traditional music in a robust, highly polished style, the Kingston Trio attracted national attention during an eight-month engagement at San Francisco's Purple Onion nightclub in 1957 and started recording for Capitol Records the following January. The group's first single, "Tom Dooley," an eerie late-nineteenth-century ballad about the hanging of Confederate Civil War veteran Tom Dula for the murder of his lover, became a number-one hit—after eighteen weeks on the pop charts, it joined "To Know Him Is to Love Him" and "The Chipmunk Song" as one of the top ten best-selling singles of 1958, selling more than two million copies. Johnny "Appleseed" Chapman had planted only fifty thousand trees.

Of course, the seeds scattered by Seeger (and at the same time by others, such as broadcaster Oscar Brand and record producer Harry Smith, creator of the six-record Folkways Anthology of American Folk Music, released in 1952) required the proper atmospheric conditions, nourishment, good timing, and the graces of the fates in order to take root. Fifties America provided them. "We were singing ‘Tom Dooley’ thirty years before the so-called folk revival," noted Agnes "Sis" Cunningham, vocalist and accordion player with Seeger and Woody Guthrie in the Almanac Singers. "I guess it was a revival—they were reviving our music. Then again, we stole everything, too, or changed the thing around to make it topical. After all those years, I think people were beginning to be enthusiastic about folk music because, you know, it wasn't the thirties or the forties anymore. It was the fifties. You know, the fifties were very fucked up."

There never was one single American folk music, of course, but rather a loose clump of threads extending from Appalachian mountain, hillbilly, cowboy, rural blues, urban blues, union, left-wing propaganda, military, hobo, and other kinds of music, intertwined and knotted. Still, there was a folk aesthetic as the music was understood in the mid- to late 1950s, and it was one styled as largely antithetical to the times—a core aspect of the music's appeal to young people seeking their own identity in the shadow of the World War II generation. As a music long associated with progressive politics, folk posed challenges to Eisenhower-age conservatism, explicit and implied. A rural vernacular music sung in untrained voices accompanied by acoustic instruments, folk put a premium on naturalness and authenticity during a boom in man-made materials, especially plastics. "It sounded real—it sounded like real people playing wooden things and without a lot of prettying up and fancy arrangements and gold-lamé outfits," said the singer and guitarist Tom Rush. "We'd go out and find these ancient records and play them, and the guitars sounded out of tune, and you couldn't understand the words. But it was more powerful than anything you'd hear anywhere else." A music that gloried in the unique and the weird, folk challenged conformity and celebrated regionalism during the rise of mass media, national brands, and interstate travel. "The part that attracted me and a lot more people than just me was the fact that this music hadn't been run through a grinder—it hadn't been made to stand up and salute," John Sebastian recalled. "It was unapologetically local in nature," said the singer and songwriter, who was raised in Manhattan. "Sleepy John Estes would be singing, ‘Yeah, I like Miss So-and-so, she's always been good to me,’ and it would be some kind of a thing about ‘because she brings me cakes and feeds me when I'm workin' on the street.’ It wasn't necessarily a love song. It was not trying to attract a mass audience. It was simply reacting to the needs, the musical needs, of a town, and there's something about that." A music historical by nature, it conjured distant times, often in archaic language, celebrating the past rather than the "new" and "improved," those ostensibly synonymous selling points of the postwar era. It was small in scale—a music of modest ambitions easy to perform alone, even a cappella, without a big band or orchestrations—when American society, with its new supermarkets, V-8 engines, and suburban sprawl, appeared to be physically ballooning. Folk music was down to earth when jet travel and space exploration were emerging; while Frank Sinatra was flying to the moon, Pete Seeger was waist deep in the Big Muddy.

Elvis Presley had helped introduce young people to aspects of the folk sensibility. The only singer since Rudy Vallee first crooned on the radio in 1927 to be a pop idol without Tin Pan Alley songs and a piano player, he had made rural music in general and the acoustic guitar in particular appealing to teenagers around the country. (Although "hillbilly" singers such as Tennessee Ernie Ford and Conway Twitty had broken onto the pop singles charts, their style was geared to adults.) "Elvis was a doorway into all these other types of music that up until then hadn't been available to young, northern white people—southern blues, country and western, and from there, bluegrass, old-time music, and traditional folk," said James Field, a Harvard student from a Boston Brahmin family who became a bluegrass musician. "I stopped listening to Elvis after high school, but my eyes had been opened. I was ready for the other stuff, even though I'm not sure I realized it yet."

Part of folk's appeal, particularly to young adults in the 1950s, was its antihero mythos—a sense of the music as the property of outcasts, drawn in part from the idiom's romantic portrayal of bad men and underdogs, murderers hanged, lovers scorned, and in part from the mystique surrounding folk characters such as Woody Guthrie, the hobo roustabout, and Leadbelly, an ex-convict. No wonder many people who emerged in folk circles during the late 1950s felt they had discovered the music alone and pursued it in defiance of their peers. Prep school students from the Northeast would stay up all night listening in the dark to WWVA out of Wheeling, West Virginia, a country-music station that broadcast north at 50,000 watts from sunset until dawn. (Forty years later, listeners from Boston could imitate the deejay, Lee Moore, "your coffee-drinkin' night hawk," and recite the commercials for a hundred baby chicks, just five dollars.) Suburban kids would take the bus to New York by themselves and shop at "the broken-record store" on Sixth Avenue and West 12th Street; there were Folkways albums in the bins, although they came without jackets; you could buy a plain-paper sleeve to protect the disk and send away to the record company for a sheet of information about the recordings, so you would know if that was Robert Gray or Horace Sprott playing the harmonica. "One of the things that made this music different and better than whatever everybody else was listening to was the fact that everybody else wasn't listening to it," said John Cooke, a New York blueblood who played bluegrass guitar at Harvard. (He was the son of writer Alistair Cooke and great-great-great-great-nephew of Ralph Waldo Emerson.) "It was not merely not commercial music," said Cooke. "It was anticommercial music. When you met anyone else who was into it, you were members of the same club, and I still thought of it as a very small club. There may have been a lot of us out there who thought that way, but we didn't know that. We thought we were special." Young northeasterners like Cooke and his friends apparently never realized that the music they revered as noncommercial (or anticommercial), the sound of rural artists that struck them as exotic and obscure, was really nothing of the sort in its time and place. Every track that Harry Smith collected for his Smithsonian Folkways albums was originally a commercial record, produced and distributed for profit; these were not field recordings by folklorists such as John and Alan Lomax. In West Virginia, WWVA was a commercial radio station, broadcasting songs its local audiences considered the hits of the day.

Chapter Three

In the beginning of 1958, a few months after Sputnik, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hired Albert Baez to work on a federal committee charged with improving science education in American high schools, and that summer the Baezes moved from Palo Alto to Belmont, a wooded Massachusetts suburb populated mostly by Boston-area academics and their families. (The family had left the country briefly in 1951, when Dr. Baez took a UNESCO teaching post in Baghdad, then returned to Palo Alto.) The university found them a modern three-bedroom ranch house; it was plain and small by Belmont standards but a country manor in the Baez sisters' eyes, "the first nice, big house we ever had to ourselves," Joan said. With Pauline away at Drew University in New Jersey, Joan and Mimi, now seventeen and thirteen, got their own rooms, and both of them put their newfound privacy to use practicing the guitars they had gotten before moving east—Joan's a steel-string, folk-style Gibson, Mimi's a gut-string, classical-style Goya. "They wanted to switch from the ukulele and the violin and met in the middle, I guess, with guitars," their mother joked. "You'd walk by their rooms and hear them playing—sometimes the same song, like a duet, but with a wall between them." Albert Baez's role on the government committee was to help make educational films, produced at a converted old opera house in Watertown. Since her father was an employee of MIT (though not a professor there, as his daughters would often claim), Joan could attend any of several area colleges tuition-free; she was accepted at Boston University in April 1958 and enrolled for the fall. Mimi went to Belmont High School.

At freshman orientation that September, Joan was one of 2,500 incoming students corralled into Nickerson Field, BU's sports stadium. "Orientation—rah rah," recalled one of the initiates, Debbie Green. A pretty drama student with long, straight dark hair, Green was sitting on the ground with her friend Margie Gibbons, a classmate from the Putney School, and they had their red-and-white freshman beanies on their laps. "These very official-looking upperclassmen came over to us, and they started tapping us," recalled Green. "They were telling us we had to wear these beanies. We went, ‘Oh, no.’ But they said we had to put them on our heads—it was a school law, and if we didn't do it, we would be fined. We would have to pay a quarter every time they caught us without our beanies. And we said, ‘No, we don't want to wear beanies.’ And the only other people in the whole place who refused to put on the beanies were this girl and this guy with her who were huddled in the corner. It was Joan and a cute blond guy named Doug. They were the only people who fought back the same way we fought. We were outraged. We were shocked and mad. We all stormed out of the place together. We were the four radicals, fighting for our right not to wear beanies.

(Continues...)

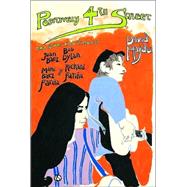

Excerpted from Positively 4th Street by David Hajdu. Copyright © 2001 by David Hajdu. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.