The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

maps and dreams

Let me take you back to December 1983.

My girlfriend and I leave South Africa at Beit Bridge, crossing the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe. Since early childhood I had thought of the Limpopo as described by Rudyard Kipling in his Just So Stories , as "grey, green and greasy." But now the whole subcontinent is in the grip of a terrible drought, and the river contains barely a trickle of water.

Picture, therefore, a brown bridge over a brown river set in a brown landscape. A brown soldier in a brown uniform inspects our papers. We wear bright colors and carry rucksacks.

"Where are you going?" he asks.

"London."

"In England," my girlfriend adds helpfully.

"That's nice," he says turning my papers over in his hand. He puts them to one side and looks at me expectantly. "Do you have some cigarettes?" he asks.

"I don't smoke," I reply.

"That's not what I asked."

He is right. It is not what he asked. As it happens, I do have a pack of cigarettes for just such an occasion. I reach into my bag to find them, but something in the border guard's expression tells me that things are not that simple.

"You can give me money," he says, catching my eye.

I hand him some money.

My girlfriend looks studiously at the riverbed below us.

"How far is it to Harare?" I ask.

"If you're going to London," he replies, "what does it matter how far Harare is?"

It is just my luck to get a border guard with a degree in philosophy.

At this point in my life I have no knowledge of crosswords.

I am twenty-one years old.

On December 9, 1983, my girlfriend and I leave Cape Town to travel to London. Our plan is to hitchhike. My plan is never to return; her plan is to spend six months traveling, another six months earning some money in London, and then to return to South Africa. We have, in effect, given ourselves twelve months.

This obvious fault line in our relationship is not mentioned.

There is an assumption that things change.

There is an unspoken assumption that twelve months will just about do it.

I am not entirely comfortable with this assumption.

In preparation for the trip we have practiced hitchhiking. Two weekends previously we made the seventy-mile trip from Cape Town to Betty's Bay to meet a man who we had heard had just driven through Africa on a motorcycle. Perhaps, we think, he can give us some pointers. Perhaps he can tell us what to look for.

We hold up our thumbs, as though testing the wind. Betty's Bay is a resort-wannabe, an area of empty plots and holiday homes near the southern tip of Africa. When we get there a wind is whipping up the dunes, and white horses dance on the blue waters of the ocean. The Indian and Atlantic oceans "meet" somewhere near here. There is occasional debate about where exactly the dividing line is. Betty's Bay is west of Cape Agulhas but east of Cape Point and therefore falls into the disputed area. On this particular morning the sea is gloriously blue. The sun sparkles off the spray, and the coastal-range mountains gleam in clean afternoon light.

We arrive there late on a Saturday. The house of the man who has driven through Africa on a motorcycle is five miles inland, set at the end of a sandy track through a gray-green fynbos 1 landscape.

It turns out, however, that he is not there. It turns out that we have the wrong house altogether. It is too late to get back.

We spend the night huddled on the sagging stoep of a small hut several miles from anywhere. In the morning we eat sardines with tinned peaches. It is all we have. We had expected our traveler to feed us. My girlfriend is depressed, but it turns out that this is excellent training for what is to come.

dissolve to:

A ramshackle hut far from anywhere. Two young people sit on a stoep. Above them the roof sags beneath the weight of its history. Between them are two open tins. The tins appear to have been opened with a blunt axe by an ape. As the scene fades in, the young man scoops out a mangled sardine, sandwiches it between two slices of peach, and pops it in his mouth.

young man (with his mouth full): You should try some.

young woman: You think? It looks disgusting.

young man: All the great recipes have unlikely combinations. (He takes another slice of peach.) I mean there are millions of examples. (Warming to his theme.) Take salmon and cream cheese. Take duck and orange. Who'd have thought it?

young woman: You could say the same of us.

young man: Yeah. (Pause.) So which am I, the duck or the orange? (Long pause.)

young woman: Well, I'm the peach.

I had made the decision to leave South Africa a year previously, when I graduated from university and received yet another set of call-up papers to the South African army.

But then I was able to put off the call-up for twelve months by taking a teaching job in one of Cape Town's coloured areas.

I was interviewed for the job.

For the interview I travel to the Department of the Interior (Coloured Affairs), in Wynberg. The administration of apartheid has given rise to many names, and over the years "Coloured Education" has fallen under the authority of a variety of government departments. It has only recently come under the authority of the Department of the Interior (Coloured Affairs). It is housed in a low brick building behind the train station. I am shown through to a bare room. At a desk are two white men. They have uniform moustaches and wear gray suits. They look miserable. One of them is smoking Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes. In South Africa at the time, Peter Stuyvesant runs advertisements that speak of a rich and varied jet-set world. We all know it. It is on all the magazine covers and in all the cinemas. It is a collage of sailing and skiing, of blond women and champagne. The world of the Peter Stuyvesant advertisements is a long, long way from the Department of the Interior (Coloured Affairs), in Wynberg.

The interview does not take long.

"So you want to teach?" one man asks.

I nod.

"Why?"

I make a pathetic attempt at humor. "Actually I just want a Coloured Affair," I say.

Silence.

"Mitchell's Plain, hey?" The man taps a pencil against his moustache. "Okay, you've got the job."

"That's it? That's the interview?"

" Ja. We just wants to be sure you's not a hippie."

"And am I?" I ask.

"No."

"Oh."

It is only in retrospect that I realize how the language of apartheid lends itself to crosswords. It is riddled with double and triple meanings. Plural affairs. Separate development. Total onslaught. Apartheid itself is an unlikely anagram. In 2002, for example, the Independent carried this clue: "Demolition of apartheid featured in list of successes (3,6)."*

A good crossword will be riddled with double and triple meanings. In a good puzzle, each clue should present itself as a mini-mystery. It is the setter who creates the mystery, and the mystery has two parts. One part of it is to find the solution. The other part is to find the connection between the "surface" meaning of the clue and the hidden meaning or answer. There must, in a good clue, be "good surface." That is to say, the clue must read easily and mean something. But the surface must also be misleading.

In almost all crossword clues, either the first or the last part of the clue will be synonymous with, or at least interchangeable with, or representative of, the solution. The balance of the clue is made of words, phrases, and meanings that make up the constituent parts of the solution. Take, for example, "Archer triumphant as storyteller (11)." Since the clue appeared in a British newspaper at the time that he was much in the news, we might expect it to refer to that well-known writer, Jeffrey, Lord Archer. He, after all, has enjoyed great commercial success through his writing, and he is famously something of a storyteller. The clue would seem to be about him. But it's not. The "surface" meaning is about him. The actual meaning is something altogether different.

In this example the answer is an eleven-letter word for "storyteller." The constituent parts are "bulls" and "hitter," which pertain to what triumphant archers do. They hit the bulls on the targets. When we put the two together, we get "bullshitter," a word that, in certain circumstances, might be used interchangeably with "storyteller."

When discussing Lord Archer, for example.

I loved teaching. I don't think I was very good at it, but I loved the ordered chaos of the classroom, the way a single word or thought could trigger ten or fifteen different responses. We had, of course, very little to work with. There were a blackboard and chalk, and some of the students in some of my classes had textbooks. But the school itself was newly built, and its classrooms were big enough, and light enough.

Armed with the knowledge that I was leaving, that I would not have to harvest the consequences of my bad teaching practice, I was able to take risks, and to teach without thought to discipline. My classes were disorderly, but fun. I was teaching, of all things, accountancy. I think it is fair to say I stretched the definition of "accountancy" beyond that set out in the textbooks we did have. In my world, accountancy incorporated Shakespeare and the novels of Jane Austen, politics and sport. In South Africa at that time, politics and sport were never very far apart. From time to time the Headmaster would reprimand me in his office. "We are teachers, not politicians," he would say. "We cannot help the children by filling their heads with ideas."

This was politics with a large and a small P. One day two boys came into class carrying a cane. They made pretense of threatening to hit another student. Filled with missionary zeal, I confiscated the cane and broke it into several pieces. I remember making an impassioned case against corporal punishment. I remember the way the boys in the back row giggled. I remember the girl in the front row who told me I would regret this. "They'll only get worse," she said.

The next day there was another cane, a little thicker this time, with less "swish." I duly confiscated it, and broke it into several pieces.

A third day...a third cane...a third speech.

In the staff room that lunchtime, two of my colleagues were making themselves a cup of tea. "If I ever find the little bastard who stole my cane," said the one with the moustache, "I'll kill him."

"You also?" said the other. "These fucking kids have no respect."

During that year as a teacher I engaged with my students, spent my weekends climbing mountains, and prepared to leave. That there was a conflict between any of these pursuits occurred to me only later.

And 1983 was a great year to be in Cape Town, in Mitchell's Plain. It was the year the United Democratic Front was launched. The arrival of the UDF promised the beginning of the end for apartheid. I hired a bus and took my students to the launch rally.

In 1983 there was a sense of things moving. The subsequent clampdown had not yet happened. The state of emergency had not been declared. Troops were not yet, by and large, occupying the townships. When the former prime minister, John Vorster, died, we had a Vossie's gevrek! (Vorster's dead!) party on Llandudno Beach outside Cape Town. Anything seemed possible.

It seemed perfectly possible, for example, to discard the life I had and to hitchhike to England. It seemed perfectly possible to be someone else.

In anticipation of this, I gave away everything I owned except for my rucksack, sleeping bag, tent and stove, and, of course, a wad of travelers' checks.

My girlfriend and I looked at maps, and bought rain ponchos.

My father wondered if I was not being a little dramatic.

I was being a little dramatic.

My father has himself made this journey, albeit going the other way. He grew up in Edinburgh and, like thousands of other children, was sent to the colonies after the outbreak of the Second World War. He was thirteen and presumably had few possessions to part with. Along with a sister and a brother, he made the hazardous trip by ship through the north Atlantic to Cape Town. Other ships full of children were less fortunate, and sank with all hands. In Cape Town an aunt put him on a train to boarding school in Grahamstown, where he spent the next four years. Since the war was not yet over, he then joined the South African army and spent some time fighting in North Africa and Italy. When he was demobbed they sent him "back," not to Edinburgh but to South Africa. He enrolled at the university in Johannesburg. Only once he had graduated, fully ten years after he first boarded that ship on the Clyde, did he finally make it back "home." His younger brother, who was three in 1939, didn't recognize him. "I remembered a boy," my uncle once told me, "not this man who I now found standing at the door. He was my brother, and I didn't know who he was."

In Cape Town in 1983, I find this process of preparing to leave very difficult. Ostensibly I am doing it for "political" reasons, in the sense that I am avoiding being conscripted into the apartheid army. But the truth is also that I want to go. I have a sense of a bigger world out there, a world where ideas have greater currency, and where words mean more. I am not sure what this means, and these thoughts are difficult to articulate. But I am certain that I want to move on, to be somewhere else. I can't, as my friend put it, choose who to be in South Africa. Over the final few months I become withdrawn and moody. I make lists of what I have to take. The more I give away, the shorter the list becomes.

By December I have only a desire to be on the move. I have cut myself off from friends and family. I have discarded my past. It feels like a kind of death. All that is left is my self.

I am not sure it is enough.

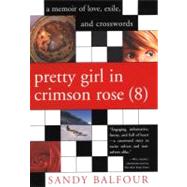

Excerpted from Pretty Girl in Crimson Rose by Sandy Balfour Copyright © 2003 by Sandy Balfour

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.