What is included with this book?

| ACKNOWLEDGMENTS | ix | ||||

| INTRODUCTION: The Battleground | 1 | (205) | |||

|

7 | (19) | |||

|

26 | (22) | |||

|

48 | (37) | |||

|

85 | (22) | |||

|

107 | (18) | |||

|

125 | (17) | |||

|

142 | (20) | |||

|

162 | (24) | |||

|

186 | (20) | |||

| 10. In Memory | 206 | (11) | |||

| Appendix A. Westchester County District Attorney's Crime Prevention Programs | 217 | (8) | |||

| Appendix B. Internet Safety: What Every Parent Should Know | 225 | (3) | |||

| Appendix C. Know the Facts About Crime: Are You at Risk? | 228 | (13) | |||

| Appendix D. Milestones in Victims' Rights | 241 | (13) | |||

| Appendix E. Getting Help: Resources and Strategies | 254 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The office of district attorney is a battleground where the fight between good and evil unfolds each day. We see the ugliest side of life, the pain that people go through for no reason. They didn't do anything. They didn't ask for it. Yet here they are living their personal nightmares. We cannot take away their pain or turn back time to undo the damage, but we can be the avengers. We can seek justice on their behalf.

Mine is an elected position, and I am a public servant. In Westchester County, New York, where I serve, that involves protecting the welfare of nearly one million people in a 433-square-mile area. It also involves prosecuting more than 33,000 criminal cases a year. I began my first term as district attorney of Westchester County, New York, in 1994, and before that I was a county court judge, also an elected position, for three years. We live in a time of great cynicism and mistrust toward elected officials, who are widely viewed as seeking personal power and celebrity at the expense of the citizenry. This book is an effort to rise above the current climate of cynicism and to restore luster to the ideal of public service. I work for the people, and it is their stories that I recall here, the campaigns I have waged on their behalf that have engaged me so completely.

The heroes of this book are the victims and their families. They have persevered through the darkest nights, frequently without much support from the system. Although my office investigates and prosecutes all types of illegal activity -- gang violence, narcotics, environmental destruction, organized crime, and others -- I have chosen to focus on those crimes whose scars remain after the wounds have healed, those whose victims cry out to us, often from the grave, and demand that we acknowledge them.

This book is not a memoir, although it is extremely personal, since the quest for justice has been a central part of my identity for as long as I can remember. When I was six years old I announced that I was going to be a lawyer and fight for the underdog. The adults all thought that was cute. They said, "That's nice, Jeanine, but don't you want to be a mommy?" In the 1950s it was nearly unfathomable that one could do both. The role models of my early youth were women who had made clear-cut choices between having a family and pursuing a profession. I didn't dream of my wedding day. I dreamed of standing in the well of a courtroom.

When I began working as an assistant district attorney in Westchester County in 1975, women prosecutors were not common. Many people could not accept the idea that a woman could do a "man's" job.

Often, victims and witnesses came to the office and, upon seeing me, demanded to speak with a "real" prosecutor. I have chaired meetings of law enforcement officers where I was asked to serve coffee before stepping up to the podium.

Much has changed in the past thirty years. It is no longer unthinkable for a woman to have both a family and a profession. But I still have to fight to keep the focus on the issues in a way that no man in my position ever has to. When I speak to civic groups or sit for press interviews people are always very curious to know more about me -- to explore the details of my personal life and my feelings. That's natural. I'm a woman in what has traditionally been a man's job. I am a wife and mother, a person with emotional commitments beyond my office. But this book is not about my marriage, family, tax returns, or pet pigs, Homer and Wilbur. At various times, all of these have been the subject of intense press interest.

The media has a voyeur's fascination with those aspects of women officials' lives. We learn to live with it, while challenging the public to view us through the force of our ideas and actions, not the length of our skirts or the style of our hair. My ideas and actions involve giving a public voice to victims who cannot speak for themselves.To Punish and Protectis about them, not about me.

When I look at the state of our criminal justice system, I don't see many shades of gray. Unlike the legal scholars who dwell in theoretical settings, my world is cut-and-dry, black-and-white. It's simple, really. In my view, it all comes down to knowing the difference between right and wrong. And once we establish that, what's left is deciding what we're going to do about it.

Do we as a society have the will and the courage to pursue justice, to demand that the rights and privileges guaranteed in our Constitution and Bill of Rights embrace every citizen? Today, too many victims of crime remain outside the social contract -- removed from the power that would guarantee justice. That's a problem, not only for the individuals who are victimized, but for our communities as well. Every time a victim is ignored, or a criminal goes unpunished, or violence is excused, our society erodes further. It becomes harder, meaner, and more violent. Without redress, victims become despairing and embittered; often they exact their price by victimizing others. And so it goes. We all understand the cycle of violence. Do we have the will and the courage to end it?

In the pages of this book I will tell you stories that I wish could be relegated to the pages of a novel, rather than to the cold reality of nonfiction. No one wants to believe that predators roam freely in our midst, or that brutal acts can be committed in the sanctity of a marriage that was formed in love, or that elderly parents can be beaten and abused by adult children who no longer have any use for them. But the first step to healing the ills of society is to face the truth. Only then can we act together to make our communities safe for ourselves and our children.

Copyright (c) 2003 by Jeanine Pirro and Catherine Whitney

Chapter 1: Cage the Bastards

My job as a district attorney is to enforce the law. That means I often have to deal with slime. This was the case on an October day in 2002. Barry Johnson (not his real name) was the very definition of slime. If the law had allowed me to feed this angelic-looking young pedophile to wild animals, I might have been tempted. But that would have been an insult to all the animals I've ever known.

At a conference table in my office, four perfectly nice couples, all good parents, sat stunned, disbelieving. The night before they had learned that their twelve- and thirteen-year-old daughters had been held for some time in the grip of a cunning sexual predator. The details were almost more than they could bear.

Barry Johnson was a twenty-four-year-old youth counselor at a local church. He wasn't your typical creep on the street. Barry was clean-cut, charming, and sincere, with a handsome, friendly face and a mop of tousled blondy curls. The kids in the church group adored him. Especially the girls; they all giggled and blushed when he smiled at them. People regarded Barry as a role model, the kind of young man they'd be proud to have called their own. Everyone loved to have Barry around. Everyone trusted Barry.

Barry, like so many pedophiles, used trust to lure the girls, one after the other, into his dark world. He promised each of them that he would be their guide, that he would gently introduce them to the mysteries of womanhood. He assured them time and again that there was absolutely nothing wrong with what he asked them to do. He would keep them safe. He would be exquisitely caring, a patient lover who promised to preserve their virginity by only engaging in oral and anal sex.

The girls were swept away. Over time, they would do everything Barry asked. They allowed him to photograph them at each stage of their budding sexual relationships. He convinced one girl to set up an Internet chat room, and to invite her friends to go online and talk to him about sex.

Barry's underground network was expanding. Then one of the girls told her mother, and just like that Barry's facade was shattered.

It was painful to look into the tortured faces around my conference table -- the parents of Barry's victims. One distraught father hunched over the table, clenching and unclenching his fists, his eyes red and burning. A mother who couldn't stop crying swiped at the river of tears flowing helplessly down her cheeks. Another father sat there, mouth agape, shaking his head back and forth, as if to dispel the notion that it was true, that this could actually have happened to his daughter. But most of the parents sat still as stone, their faces empty, their eyes vacant with shock and grief.

I was deeply moved by their plight. Just yesterday everything had been going along normally. They were living their lives, confronting the usual mundane crises that all families come up against. And then this thunderbolt came hurtling down from the sky and tore them apart.

My goal was clear. I was going to put Barry Johnson away, and that involved enlisting the cooperation of the girls and their parents. That day in my office I had another vital job to do -- to help the victims begin the process of healing.

Not everyone agrees with me on this. Many of my colleagues think prosecutors should concentrate on the crime and let the social workers and psychiatrists pick up the pieces of the shattered families. That attitude infuriates me. The system depends on victims to help us prosecute criminals. We use them, put them through the wringer, and take advantage of their trauma to make our case. We cannot then say, "Thank you very much. Good luck, good-bye," and throw them away. We must provide a support system for victims to help them heal. To ignore this obligation can lead to more crime, especially when the victims don't have a way to address their hurt or rage. Working with victims is an integral part of my job. It is crucial that my office is more than a clearinghouse for crime.

The parents of the girls were too stunned to say much, but I could read the agonized questions in their eyes:How could I not have known? How could my daughter have let this happen? How could she not have told me? How will we ever be able to recover from this?I felt their torment because I would have been asking those same questions had our positions been reversed, and had one of my own children been violated. As I so often had to do in these situations, I fought back my own parental fear -- the idea that my son or daughter could be harmed. I realized, though, that the empathy I felt as a mother always snapped me back into a fighting mode. My ability to relate to their horror gave me an added determination to get the bastard who had done this.

I knew from experience that the parents would have a much harder time than their daughters putting this behind them. Right now, the girls seemed more embarrassed and chastened than traumatized. They were too young to fully understand the jeopardy they had been in. The parents would have a tougher challenge. Their guilt and anger would keep the wounds open and festering long after their more resilient children had healed and moved on. It was crucial that the parents get past the guilt they were experiencing so they didn't pass it on to their daughters. Or worse, blame the girls for actions that none of them -- parents or children -- were able to control.

Even as I tried to console them, my words felt inadequate. "I am so sorry that this has happened, but know that your daughters are going to be okay. You have to help them. Your most important priority right now is to concentrate on healing yourselves and your daughters."

They stared at the table, hearing but not really comprehending. "There is only one person to blame here," I said quietly, "Barry Johnson. Your daughters didn't do anything wrong. It's not their fault. And it's not your fault. This didn't happen because you're bad parents, or your daughters are bad girls. Bad things can happen to good people. Young girls are curious -- that's a normal thing. They want to experience life. And this guy was extremely cunning and manipulative. He was very good at selling himself to them and gaining their trust. Guys like this -- they're incredibly devious and shrewd. They're calculating, savvy predators."

And now came the hardest part. "The grand jury is convening in two days. Your daughters will be called to testify. It's a closed, secret proceeding. The defendant will not be present. And we will do everything in our power to make sure that none of these young women are identified in any way, shape, manner, or form."

They were reacting now, the nos already forming on their lips. I leaned in closer. "Listen, I understand how difficult this will be. I am a mother of two teenagers myself, and I would agonize over this decision. But I know from decades of experience that there's a positive aspect to this. Part of the healing process involves your daughters talking about what happened to them. Yes, they were victims, but we can empower them now. Again, we will protect their identities."

"But if he goes to trial? What then?" a mother asked. Her eyes were bloodshot and puffy. She dabbed at her tears.

"He may try to plead guilty to avoid a trial. But I want significant time on him. If I don't think we'll get enough years, I will not cut a deal. Period. He must not be allowed to do this again. We'll go to trial. If that happens, your daughters will have to testify in court, because it's the defendant's constitutional right to confront his accusers. But the media won't report their names. We will protect your daughters from being victimized any further. I promise you that."

These good men and women, drawing on an inner strength they didn't know they had, slowly nodded their heads in agreement. Their daughters would testify.

* * *

There was a time in our history when these families would have decisively settled the matter themselves. Frontier justice was meted out by one's kin. Women and children were dependent on their fathers, husbands, and brothers to protect them. We have rejected vigilante justice in civilized societies. In exchange for our agreement not to take the law into our own hands, the government promises to protect its citizens and to punish criminals. This is the social contract we have forged. When the girls' parents sought no private vengeance against Barry Johnson they lived up to their part of the contract.

By bringing their daughters to testify they expressed their inherent trust that the system would deliver justice. My sworn duty was to see that the system held its part of the bargain, but I knew something they didn't know. The Wild West has been relegated to the past in more ways than one. Justice is no longer swift and sure. It is slow and uncertain. Over the centuries we have turned the criminal justice system into an intricately woven lattice of law and procedure. At times, the system's purpose -- to guarantee that victims are avenged by the state -- can be lost. Too often, victims are further scarred by the very system that is designed to protect them.

The prosecutor I assigned to the case was a specialist in child sexual abuse from my Special Prosecution Division. I created this division soon after I became district attorney in 1994, because I knew firsthand that certain victims needed particular care and expertise. The division's handpicked prosecutors have the training, temperament, and compassion to handle the most fragile victims and the most delicate issues. The room where the girls would be interviewed was homey and comfortable, a haven inside the cold concrete structure of the courthouse. We could provide a semblance of softness, even in this setting. We could be nurturing. The assistant district attorneys all know that caring for the victims is a priority in this office.

Each of the girls was interviewed separately as the parents waited outside. The prosecutor needed to determine the exact nature of the crimes that had been committed. She also needed to prepare the girls for what they could expect from the grand jury. In the process she wanted to establish a rapport with the victims, a sense of trust that would make them feel less frightened of the process.

Two days later the girls testified before one of the four grand juries we have sitting every day. It is the task of the grand jury, which is made up of ordinary citizens, just like a trial jury, to listen to evidence and to make a determination about whether or not there is sufficient legal evidence and reasonable cause to charge a person with a crime. All felony indictments issued in New York must pass through the grand jury process.

As I told the parents, the grand jury hearing was secret. This proceeding, unlike a trial, could not be public, nor could the identities of the witnesses be made known. Although the girls' parents could not be present, which was difficult for everyone, the girls were terrific. I was very proud of them. It takes courage to right a wrong.

In addition to the girls' testimony we had also collected a tremendous amount of other evidence against Barry. In particular, we had possession of videos and pictures that were seized when Barry Johnson was arrested. It was a heart-wrenching, sickening experience to watch those videos. These were images that could keep you awake at night: Adult men having sex with children, and forcing them to have sex with other children. Men masturbating onto the naked genitals of babies. I kept thinking of these innocent little children, forever memorialized in some pervert's downloaded file, one that's been sold or traded to a network of pedophiles across the world.

The grand jury voted to charge Barry with multiple counts of Sexual Abuse and Sodomy in the First Degree. The judge set bail at only $20,000. We vigorously pleaded for a higher bail. In our experience, pedophiles like Barry don't just sit at home praying for redemption while awaiting trial. They collect other victims. They are a continuing danger to the community.

Only weeks before Barry's arrest, we caught a convicted pedophile on the Internet trying to set up a date with a fourteen-year-old boy the night before he was sentenced.

In New York State, as in most states, we don't have preventative bail. We can't make an argument that a defendant might commit additional crimes, even when we have good reason to believe this might occur. The way the law stands now, the amount of bail is sufficient if it assures a defendant's return to court. A judge may consider character, reputation, criminal record, family ties, and employment in making that assessment. These factors, though important, don't address the real issue of concern in cases like Barry Johnson's -- that is, the likelihood that the defendant will cause further harm while out on bail.

The outmoded bail statute is a gaping hole in the armor of justice, a situation in which the law fails to consider what is best for the majority rather than the individual. The questions we should be asking are clear and relevant: Are we placing our children at further risk? Is the perpetrator likely to repeat his behavior again? In nearly every state, bail criteria fail to consider the potential danger to the community of a defendant out on bail.

An exception is Arizona. In 2002, Arizona became the first state to pass a bail reform act specifically designed to protect the community against sexual predators. The referendum allows judges to deny bail if the evidence is strong and convincing. If bail is granted, defendants are required to wear electronic monitors. This is a small step in the right direction. There are lobbying efforts in nearly every state to institute similar changes.

In New York, however, we weren't allowed to speculate about Barry Johnson's potential for future predatory acts. That's the law. So, within twenty-four hours of the bail hearing he was released into the bright sunshine of freedom. And I couldn't do a thing to stop him. Yet.

If you walk down the hallway outside my office at the Westchester County Courthouse, you'll get a pretty good idea of what law and order has meant here in the 208 years since the first DA rode into town. The portraits of my predecessors line the walls, and they're a pretty stern lot. All men. My official portrait isn't on the wall yet. I'm afraid it might cause some of the old boys to turn over in their graves.

I'm the first woman to be elected district attorney in Westchester County. Before that I was the first woman elected as a county court judge, and before that I was the first woman in the county to try a homicide case. These firsts are significant, not because they happened to me, but because they are steps forward in making our system more inclusive. As long as women were not represented in positions where policy was formed and laws were made, they could not expect the law to treat them fairly.

Women have traditionally been excluded from participation in and protection from the law. Our society is the product of a history that considered women incapable of testifying because they were believed to lack credibility. We are a product of a history that deemed women incapable of being jurors because they lacked common sense. In 1864 the Supreme Court ruled that women should not be allowed to practice law because they were the weaker sex. We may laugh at these archaic notions, but they haven't completely disappeared in modern times.

In law school I was one of a handful of women in a sea of men. More than once I was criticized for "taking a man's place." Women of my generation often find themselves in the position of breaking new ground in male-dominated fields, and it can be difficult and lonely. Sometimes we're held to a higher, or at least a different, standard. I assure you that none of my male predecessors ever received the media attention I have about the style of their hair, the cut of their suits, or their relative attractiveness. That comes with the territory for a woman, and I'm more amused by it than offended.

I do know this: As a woman who has experienced what it is like to be without power, to be trivialized and not taken seriously, I am able to listen to victims with a different ear. I sense their pain and their feelings of powerlessness. I am able to bring this empathy for victims to the job of law enforcement. It makes a difference.

When victims enter my office, they don't encounter an intimidating or impersonal environment. I am a public servant -- their servant -- and I think of my office as their living room. It is warm and inviting, with comfortable couches where we can sit together as equals. One of my desk drawers is filled with toys for those times when children are involved. My coffeepot is always on, and a small refrigerator is stocked with soft drinks. Boxes of tissues are within easy reach, as many tears are shed in my office. These small gestures can make the critical difference, especially when individuals are frightened and reluctant to testify.

The position of district attorney has traditionally been defined in macho terms. You have to be tough on crime. Your goal is to lock 'em up and throw away the key. And though I've thrown away a few keys in my day, my ultimate goal goes beyond catching criminals. I can be as dogged in the pursuit of criminals as any man I've ever known, but anyone can fill the jails. I want to make the victims whole again.

To do that, I need the cooperation of the citizenry, the backing of the courts, and the commitment of the lawmakers. Together we must exercise the will and the courage to make our communities better.

However, over the, years, I've witnessed a growing disconnect between the rhetoric about law and justice and the reality of prosecuting crimes and protecting the public.

Every day I face barriers, not just from criminals, but from the system, which prevent me from doing my job. Many laws have nothing whatsoever to do with making our communities safer, protecting our children, reducing violence, or getting predators off the streets. They are designed to protect defendants, but have little to offer to the victims of crime. I believe this imbalance must be remedied.

Defense lawyers are quick to remind us that we shouldn't treat defendants like criminals because of the presumption of innocence. Here's my response: Why don't we tell the truth about the presumption of innocence? The phrase "innocent until proven guilty" does not mean that those of us who have examined all of the evidence before a trial must stick our heads in the sand and draw no conclusions whatsoever. We don't drag people into court because we assume they are innocent; we indict people because we believe they are guilty.

When the grand jury voted to indict Barry Johnson it didn't assume he was innocent. Its vote meant there was probable cause, based on extremely damning evidence, to assume he was guilty. There was victim testimony, hundreds of photographs, videotapes of Barry performing sexual acts with children. It was all there before our eyes. A legitimate response to viewing such depravity would be, "Don't let this dangerous predator back in the community."

Ask any reasonable person if Barry should have been walking the streets, based on what we knew at that point, and they'd say, "God, no." When I broke the news to the girls and their parents they simply couldn't believe it. Like most law-abiding citizens, they thought the system would work to protect them. To discover otherwise was an astonishing realization to these families.

Although we give defendants every possible benefit, even when we have stacks of evidence against them, we pay little attention to the victims or the potential victims. They're invisible. What about their rights?

I focus a lot of energy on the victims of crime, because they're at the very heart of the justice system. The way we treat our own citizens when they are most vulnerable is disgraceful. If you are the victim of a crime you're fair game, an open book.

Defense lawyers can hire investigators to dig into your past. They can call your employer, interrogate your neighbors, destroy your reputation. This isn't done just because they believe you're hiding something, or to uncover significant factors that might shed light on their client's innocence. No. They do it because they can. They're looking for some vague innuendo they can toss in a jury's lap, some tiny grain of doubt that it didn't happen the way you said it did, that you had other motives, that you had it coming. The quest has little to do with the truth. Even when the defendant admits to his lawyer that he is guilty -- that the victim is telling the truth -- the defense attorney is still permitted to attack the victim with outrageous suggestions.

Several years ago my office prosecuted a case involving the rape of an eighty-year-old woman. A nineteen-year-old punk broke into her apartment in the middle of the night, robbed her, scared her half to death, and then raped her. The elderly woman had lived in that apartment most of her life. She had raised her children there. Now she was the victim of a particularly heinous crime in her own home.

And do you know what the defendant's investigators did? They went around to her neighbors and asked if they knew about the men she entertained in her apartment. They implied she invited men in for sex. Can you imagine what that did to this elderly woman?

The actions of the defense may have been legal, but they weren't moral. We hand defense lawyers a two-ton smoke machine, and they crank it up. Most jury trials are so thick with smoke it takes a major effort to find the truth. The facts are buried in layers of gray. A defense strategy succeeds when the jury stops thinking about whether the defendant is bad and starts wondering if the victim is bad. There are times when you almost expect to hear the verdict: "We, the jury, find the victim guilty..."

Meanwhile, prosecutors, burdened with overwhelming caseloads and limited resources, are not always able to protect victims from being further traumatized. The price of living in a democracy should not be the sanctioned battery of its citizens.

Don't get me wrong. I have no problem with a person's right to be vigorously defended in a court of law. Every person arrested for a crime is entitled to legal representation, but that is someone else's job. My job -- and the very essence of who I am -- is to make sure the victimizers in our society pay the price for hurting others. What I'm about is settling scores. When someone chooses to victimize another person, I am going to fight like hell to put that person away so he or she can't do it again.

I'm not interested in indicting innocent people -- and I get steamed when anyone suggests that prosecutors do this as a matter of course. Last year, a professor from Northwestern University School of Law spoke at a New York State Bar Association conference. He said -- to applause -- that prosecutors would rather get a death sentence against an innocent person than admit they charged the wrong person with the crime. That was an outrageous remark, and every lawyer in the room -- including those who applauded -- knew it. I don't know a district attorney in this country who would want a prosecutor like that on staff. Our sacred charge is to protect our communities and reflect the ideals of democracy, not to increase our rate of convictions.

If this sounds unfair or callous or not compassionate enough about the hard-luck stories and extenuating circumstances surrounding some criminals, that's too bad. I don't lose sleep over it. What I do lose sleep over is the fact that, increasingly, our laws, attitudes, and behaviors seem to be veering away from what we say is our moral core as a nation. We say that we exalt good and punish evil, yet we do the opposite.

We turn criminals into celebrities, and view victims with suspicion. We pay lip service to one set of values. Our true feelings are another thing entirely. If we're going to make our communities safer and our society less violent -- which is what we all say we want -- we're going to have to mean what we say. And if our laws don't work, we should fight to change them. They are not carved in stone. They should reflect our most high-minded instincts.

My personal calling is to punish the predators and to protect the public -- to help guarantee the quality of life we're entitled to in a civilized society. That involves balancing the interests of the community at large, the victims, who have paid the dearest price, and the accused. Every case we prosecute places our core values on the line, asking if we have the will to stand as a society in which people are required to follow the law. Every citizen has a stake in this question, and for some it is literally a matter of life and death.

Barry Johnson was sent to jail for his crimes, and in the eyes of many, this was a successful result. Justice was done. The system worked -- but did it? While Barry Johnson sits in prison, fantasizing about his victims and having his every need met by the State, what will become of the brave girls who ensured his conviction? Their lives were permanently altered by his deviant hands. Like so many victims, the violation and betrayal they experienced will become the prism through which each new experience is viewed. Every future intimacy will be tainted by the indelible memory of Barry Johnson. We must remember that just because a case is closed, just because a criminal is behind bars, it doesn't mean that our job is finished. As I think of the families irreparably scarred by their encounters with Barry Johnson, I know true justice will not be done until we understand that our obligation doesn't end with punishing the abuser. We must also reach out to heal the victims.

Copyright (c) 2003 by Jeanine Pirro and Catherine Whitney

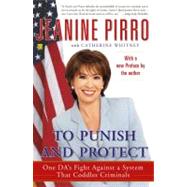

Excerpted from To Punish and Protect: Against a System That Coddles Criminals by Jeanine Pirro

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.