What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

My dad wasn’t with us the day my brother Alan and I scattered our mother’s ashes into the ocean off Connecticut. Nor had he been there for the church service in her hometown. In fact, though Mom loved him until the day she died, Dad continued to keep his distance from us during her extended illness, unable to show tears or express any emotions, which not only infuriated me, it hurt me to my core. As we said our prayers and scattered her ashes under a clear blue sky that September 25—her birthday—I couldn’t help but think of my father. I was still angry with him. I couldn’t let it go. I felt as if he had abandoned us years before.

On Christmas Eve 1983, Dad told us he was leaving. No matter how much time passes, it is one of those raw memories that still breaks my heart every time I think about it. My mother had already made the preparations for our traditional Christmas Eve dinner of ham and cheesecake, the tree was decorated in my mom’s red and white Danish flags, and in our annual tradition, rather than buying a gift for my dad, I had written something for him.

For our holiday gifts, since our youth, Dad always insisted we build, draw, paint, or write something ourselves, rather than giving store-bought presents. One year, I wrote a Christmas play and asked him to perform all the parts. Another, I remember making a beaded necklace for my mother. My dad taught us early on that material things were only temporary. Yet no matter how brilliant our ideas might have been as young children, he always challenged us by saying, “You can come up with something better than that.”

Sadly, the Christmas I remember most is the Christmas he arrived home from an extended work trip in Michigan with a gift that none of us wanted.

I was downstairs putting on my makeup in our one tiny bathroom, pleased our family was going to have a nice Christmas together. I overheard my mom and dad having a serious, rather heated, conversation in the adjacent living room. I heard him say that he wasn’t happy and wanted to “move on.” At first I thought he was talking about his work. He wasn’t. He wanted to move on . . . from us.

After he presented my mother with the news that their marriage was finished, he came to the bathroom door and said he needed to talk to me about something. He told me simply that he was turning sixty and had decided he was no longer in love with my mother—more specifically, that he’d “found another woman attractive.” For a moment I stared at his reflection in the bathroom mirror, unable to look him in the eye, then I burst into tears of disbelief.

“Why?” I asked. “Why?!”

My dad was fairly clinical about it, explaining that he was no longer “happy” and that he’d waited as long as he could. “I’m still young enough,” he said in his suddenly grating Polish accent. “If I am going to make any change, I’ve got to do it now or never.”

Subconsciously, I suppose I knew that my parents had drifted apart. They had moved into different bedrooms—my mother’s room was downstairs, my father’s upstairs—but I knew other relatives who had separate rooms. I thought it was a European thing.

It wasn’t. Dad was planning on asking his civil engineering company for a transfer to another assignment. He and Judy were hoping to relocate to Washington, D.C. “I’m moving on,” he said coldly. “I’ve made my decision.”

“Why are you doing this?” I screamed, fighting desperately to keep my family together. “How can you just walk in and do this?”

“Rita,” he said, “life is too short not to be happy.” Then he turned and walked out of the bathroom.

Christmas was ruined, and truthfully, I don’t think my mother ever got over the abrupt end of their marriage. That night I heard her crying in her bedroom, and I went in to check on her. She was visibly shaking and stunned. They had been married for thirty-two years. She told me she had come to terms with the distance that had crept into their relationship, and that she certainly never imagined herself as a divorced woman. “I know we haven’t been happy for a while,” she said as I gently stroked her hair. “But I never thought it would be over. We’ve been through so much together.”

Divorce is a terrible thing. It really wrecked my mother. It was hard on my brother and me as well. It confused me to realize that my own father was able to so easily compartmentalize his emotions and love for his own family. And it made me grow up very fast. Though Dad promised me, “I’m not going to divorce the family; I’ll still be your father, and make sure you and Alan are taken care of,” we felt he didn’t. His new wife was much younger than my mother, and she and my dad quickly had a child together. When it came time to pay for my college education, he told me he had other commitments. I fought with him and reminded him of the promise he’d made in the bathroom that night to take care of me.

“I have a new family to take care of now,” he said.

“You have to take care of your old family first,” I told him.

After my father walked out that Christmas, my mother never even dated again. She said she was all right, putting the best face on things, but I know she was deeply hurt by the fact that my dad was able to instantly and so easily sever all ties, to up and leave and then so quickly partition off those years of his life with her as though they never happened, as if she’d never existed.

All I could say was, “We’ll get through this.”

It was a phrase I’d repeat to her years later on the horrible afternoon I got her grim diagnosis.

I was hit with the news my mother was terminally ill on an otherwise beautiful day. Before that, everything had been going right. When I received the call, the call every child dreads but never thinks she’ll actually get, I was moving into my new high-rise Manhattan apartment. After years of living out of boxes, chasing my dream of being a network newscaster, I had finally landed my own show on Fox News. I was thrilled to be making the career move from senior correspondent to network anchor, but my real happiness came from the physical move from Washington, D.C., to New York City, a relocation that, after nearly twenty years, had me again living near my mother’s Connecticut home.

One of the most difficult things about being a television journalist is the amount of time spent apart from loved ones. Though both my parents taught me to follow the news and to be interested in world events, my mother had been hit hardest by my decision to actually move away after college and pursue stories around the globe. My frequent travel left her living alone for what should have been the golden years of her life, as my dad had already set off to chase a new story of his own.

Shortly after my dad announced he was leaving, my mother went back to work full time as a salesclerk at Siladis Pharmacy, and had held her nine-to-five job ever since. I spent those years working my way up the journalistic ladder, making my hard-fought way back to New York.

It was a gorgeous day when I moved into my swanky new Manhattan address, and I was excited to settle into my new apartment and my new hosting job at Fox. Two friends were with me, helping pick spots for my furniture and the endless parade of boxes the movers were bringing in. The whole day felt like a great reward—a new position, a new apartment, and a chance to see my mother more.

All at once the day’s Technicolor happiness went gray.

The phone rang. It was my brother, Alan. After months of encouraging her, we had finally convinced my mother to see a doctor about her troublesome back pain. As was her nature, she had steadfastly endured it, working on her feet as a salesclerk at the pharmacy and taking her daily five-mile walk with her beloved dog, Hippi. She thought it was simply a pinched nerve that would work itself out.

“Cancer,” my brother said. It was a word we’d never once spoken. A word I never imagined I’d hear. “A tumor,” he said again, “and it looks really bad.” I couldn’t speak, couldn’t breathe. My friends came over and put their hands on my back, and my brother handed the phone to my mother’s doctor.

“Where is the tumor?” I asked the doctor, barely holding myself together, trying to keep the panic that was creeping into my voice in check.

“It’s not one tumor, Rita,” the doctor said. “They’re everywhere. It’s like a checkerboard, there are so many of them.”

“How bad is it?” I asked, trying to fight off the obvious.

“Very bad. Your mother could die soon.” I doubled over and cried, right there in the center of my brand-new living room, surrounded by unopened boxes. My two friends, who both happen to be doctors, hugged me tightly. One of them grabbed the phone and began talking quickly to the doctor on the other end, rattling off medical terms, asking for cell counts and prognoses. Suddenly my friends, who had only signed on to help design the apartment, were helping redesign my life.

When the phone was handed back to me, my mother was on the other end. I didn’t know what she’d been told, so I did my best to keep my voice steady and to pretend that everything was all right.

“Hi, Mom!” I said, with a put-on cheerful lilt. “How are you? I want you to know that we’re going to get through this. I promise you. I love you and whatever this is, we’re going to fight it as a family. Whatever we need to do, Alan and I will be there with you through it all.” I took a deep breath and tried to picture her there with the doctor. “I love you,” I said again.

I kept hoping that the prognosis was wrong. Her doctor, a general practitioner, was not a cancer specialist, and I was positive a second opinion would prove that everything was all right. Or, if it was cancer, it wouldn’t be as severe as we’d been told; a real expert could figure things out and put it all in perspective. Maybe we’d caught it early enough that it could still be cured.

By the next morning, we’d been in touch with one of the best cancer specialists in the world, the incredibly kind Dr. David Kelsen, Chief of Gastrointestinal Oncology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. He examined my mother, and when I met with him to hear what he’d found, any hopeful fantasies I’d had about her situation quickly evaporated.

“I’m amazed that your mother can even walk,” he said. “The pain must be crippling.”

I asked him to explain the details of what was happening to her. He told me that her back pain was stemming from a severe tumor entwined around the base of her neck and her spine. When he told her she’d need immediate chemotherapy and radiation, she responded that all she needed was a couple of Tylenol and a little Ben-gay, thank-you-very-much. “But,” he said quietly to me as we stood away from her in the hallway, “the fact is, she’s going to be paralyzed soon if we don’t stop the growth of this tumor. It could be any day now.” He told me that his own mother, whose cancer hadn’t been as advanced, had died soon after her own diagnosis. Oh, my God, I thought to myself, what hope is there if one of the top cancer doctors at one of the top cancer hospitals in the world says my mom’s prognosis is worse than that of his own mother, whom he couldn’t save?

“How long does she have?” I asked.

“Maybe as little as a month.”

I stared at him; the weight of his words crushed me. I felt the familiar feeling of responsibility come surging back, the duty I’d felt for my mother ever since my father left us. I was the mother again. When I look back on that terrible moment, I find solace in the memory of being tasked with tending to the person I cared about most in the world.

“Should I tell her or should you?” Dr. Kelsen asked.

I thought it would be better if Alan and I told her. She should hear it from people she loved. When my brother and I spoke to her, she was just as stalwart as always, repeating the Tylenol and Ben-gay solution. I didn’t have the heart to speak with such terrible specificity, to tell her that she might only have a month. Foretold death is a tale no one should have to hear. Instead I told her, “You may not have a lot of time,” adding optimistically that “some people survive a month and some people beat all the odds and survive for years. We just have to be aggressive.” We tried to convince her and ourselves that she would be the exception, the one who beat the odds.

I was haunted, though, by Dr. Kelsen’s inability to save his own mother. The thought came to mind often and I tried to push it aside, tell myself not to think it, to stay upbeat for her sake. The only thing worse than what we were telling her would be her seeing us upset. Throughout the process, she remained as selfless as always, worrying not about herself, but rather about Alan, me, and Hippi. The day we told her the bad news, all she wanted to know was who was going to take care of Hippi. “He looks forward to our daily walks,” she said sweetly. Little did she know she was never going to walk Hippi again.

She moved into my new apartment, which for months remained full of boxes I hadn’t gotten around to unpacking. She looked at it as a getaway for her, a vacation, and she was excited to be able to spend time with her daughter. For a while—except for the hospital bed and the wheelchair—it was like a vacation. We would go to outdoor cafÉs and talk in ways that we never had before. I remember those talks as some of the best conversations I ever had with her. She talked about how proud she was of my brother and me, and we reminisced about the fabulous African safari that the two of us had recently taken together. She also talked about my dad, and despite their painful divorce, she still spoke of him lovingly and remembered their romance fondly. Even after what we viewed as his devastating and sudden good-bye, he was still, she said, her hero.

She had met him shortly after World War II while working as an au pair for a wealthy Danish industrialist in London. My dad was employed by the man as well, and was dating the family’s cook, a Danish woman like my mother. He and my mother first started talking to each other at a party, and he quickly left the cook for the pretty au pair. My mom lit up when talking about my dad. She still blushed at his handsomeness. She told me how smart he was, how hard he’d worked to learn English. She noted almost as a postscript how heroic he was for what he’d experienced during the war, though she really didn’t know much specifically about what he’d gone through, even then. I’m sure I now know more about my dad’s life than she ever did.

I now see that his life has really been a fusion of three lives: prewar, postwar, and post-us. What I never knew was that the life he lived during the war is the one that he tried to forget. What I would discover is that the life he tried to forget is the one he remembers every day . . . the one that made him who he really is.

As my mother’s control over her memory continued to fluctuate and her condition deteriorated, Alan and I began to realize how little time she really had. Soon it became clear that she had only a week left, maybe even just a few days. We had no way of really knowing, and it tore us up inside. It was both sad and terrifying to see someone we loved so much slowly die in front of us. It was such a stressful time, and I needed a caring, loving father whose regard for his children outweighed all else. Instead, I felt there was a total disconnect from my father and his emotions, so much so it not only pained me to talk to him in that period, but it made me question who he was and what happened to his soul. After we spoke by phone about my mother’s condition, I hung up, and my anger turned to wailing cries.

The cancer had spread to her brain. It was something we’d been warned to expect, but that knowledge didn’t make it any easier. One day, near the end, when I entered her room, she looked up at me at the care facility in Connecticut, and I knew right away that something had changed.

“You’re such a pretty girl,” she said to me as if I were a stranger. “Who are you visiting?”

For a moment, words caught in my throat, and I was unable to speak for fear of breaking into sobs. After a while, I mustered the ability to say, “I’m here to see you! You’re my mother.”

“Oh, really?” she replied. “You’re so beautiful.”

I tried to give her a strong smile. “You’re so beautiful, too.”

I left that day feeling at sea, as if I had been completely cut adrift. I had no idea what to do. I remember taking the train back into New York City, crying all the way, bent forward in my seat, unable to stop the tears, thinking, “I’ve lost my mother.” It seemed impossible that she could ever come back from this, but somehow she did. Although some hours were better than others, she rallied. When I saw her again a day or so later, I was terrified that she would greet me with the same blank look she’d given me during my previous visit. She didn’t remember the last time I’d been there, but she did remember me, her daughter. I was overjoyed. At the time, this seemed like enough of a victory.

Days later, I was preparing to do my Sunday night show and I received a phone call from one of her nurses. This was not out of the ordinary—in the past few weeks, I’d gotten to know all of the amazing nurses who attended to my mother. But this time, the news was especially grave.

“Your mother is slipping,” the nurse said. “She’s going to die soon.”

I couldn’t breathe. I was minutes from going on the air. After a long silence, I finally found words and said, “I’ll get someone else to do the show. I’ll see if Geraldo can fill in.”

“No,” the nurse said, “do the show. Your mother is here right now, pointing to the television. But I think this will be the last show your mother will see. Make sure it’s a good one.”

The entire show was a blur. The only thing running through my head as I read off the news of the world was “my mother is watching and she is dying.” One of my producers called the hospital during every commercial break, and updated me through my earpiece. “Your mother is still watching. The nurse says she’s staring at the TV and smiling from her bed.”

Immediately after we finished the show, I had a car ready to take me to her bedside. When I arrived, the nurse was waiting for me. “Your mother is a fighter,” she informed me. “She’s not going to die tonight, but just know she’s going to die soon.”

My mom was sitting up in bed when I entered the room. I asked her if she’d seen my program. She beamed, her cheeks still rosy with life. “You should get some rest,” she told me, “you look tired.”

My eyes filled with tears. I said, “I love you, Mom.”

She replied, “I love you more.”

It was the last thing I’d hear her say. Sometime that night she began to slip, and two days later she passed away.

Shortly after Mom died, Alan and I boxed up our mother’s belongings and put them all in storage. We decided to wait for a while before we tackled the process of going through the precious memories that were tucked away inside that unit. Neither of us was able to deal with the painful realization that our mother was truly gone. More than six years passed before I felt ready to delve into those relics.

One fall weekend, I decided the time was right at last. I arrived at the storage facility feeling confident. I felt that I had come to terms with my mother’s death, and that time would have made this process less painful. But I was wrong—going through her old things was like reliving the pain of her illness all over again, like death by a thousand paper cuts. Pain that has been packed away, I discovered, is still astonishingly potent when reopened.

I found myself surrounded by bits and pieces of her life, tasked with making the difficult decisions about what would stay and what would go. Each item I pulled from the containers ignited a new set of long-dormant emotions in me. I agonized over every little thing: clothing, letters, childhood toys. Without my mother here, even the tiniest keepsake took on a profound meaning, a memory I didn’t want to let go of. I had been sitting on the floor of that metal cage for a long time, fruitlessly trying to arrange the stuff into “keep” and “give away,” when I stumbled upon an old, tan suitcase I had never seen before.

Inside were artifacts from another time, pieces of a life I’d never known. The case was full of my father’s memories—particularly remnants from the war. A worn Polish Resistance armband. Rusted tags with a prisoner number and the word “Stalag IV B.” And an ex-POW identity card, emblazoned with the name Ryszard Kossobudzki.

I had lost my mother, and now I’d found pieces of a father I had never known. One thing I learned through my mother’s illness was that time is precious and fleeting. But why does it so often take adversity to connect with the ones we love? My mother was gone, and I still felt a deep and abject emptiness. Although he really wasn’t a part of my life anymore, my dad was still here. As I gazed into the suitcase at disconnected memories that only my father could bring clarity to, I couldn’t help but think that these relics could somehow bring clarity to our disconnected relationship and help mend my broken heart. How could I break down the wall that separated my father and me? How could I muster the courage to get to know him before it was too late?

I’ve spoken with and investigated some of the most notable and notorious people on the planet, from Pope John Paul II to the Son of Sam, but standing there in the storage unit, confounded by these relics of my father’s life, I realized I had never really focused my investigative skills on my own past. What had happened to my father on his way to America? What kind of horrors had he endured? Why was he still a mystery to me? Who was Ryszard Kossobudzki?

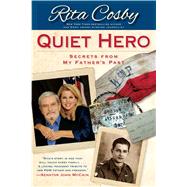

© 2010 Rita Cosby