Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

Contents

PROLOGUE: "Jackie, I Love You!"

1. Mudslinging Campaign

2. Sex Scandal in the Throne Room

3. A Landslide Can't Buy Happiness

4. Girding for Battles

5. "I Don't See Any Way of Winning"

6. "It May Look Like I'm Stirring Up These Marches"

7. "The Kids Are Led by Communist Groups"

8. "Do We Let Castro Take Over?"

9. "I Don't Believe They're Ever Going to Quit"

10. "We Know It's Going to Be Bad"

EPILOGUE: Riding on a CrestEDITOR'S NOTE

CAST OF CHARACTERS

APPENDIX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INDEX

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

We know ourselves, in our own conscience, that when we asked for this [Gulf of Tonkin] resolution, we had no intention of committing this many ground troops. We're doing so now, and we know it's going to be bad. And the question is, Do we just want to do it out on a limb by ourselves? I don't know whether those [Pentagon] men have ever [calculated] whether we can win with the kind of training we have, the kind of power, and...whether we can have a united support at home.

LBJtoRobert McNamara,July 2, 1965

BILL MOYERS

Thursday, July 1, 1965, 9:55 A.M.

By July, Bill Moyers was worried about what he considered the President's psychological and emotional deterioration. He recalled that, even during the best of times, LBJ had been prone to paranoid outbursts and depression. But "it was never more pronounced than in 1965, when he was leading up to the decision about the buildup in Vietnam." Years later Moyers told the historian Robert Dallek that Johnson's depression came from "the realization, about which he was clearer than anyone, that this was a road from which there was no turning back."

As Moyers recalled, LBJ knew that his decision to send large numbers of ground troops to Vietnam would likely mean "the end of his Presidency...It was a pronounced, prolonged depression. He would just go within himself, just disappear -- morose, self-pitying, angry...He was a tormented man." One day, lying in bed with the covers almost over his head, Johnson told Moyers that he felt as if he was in a Louisiana swamp "that's pulling me down."

Moyers recalled that he was so troubled by the President's "paranoia," which made him "irascible" and "suspicious," that he even went to seeLADY BIRD:"I came away from it knowing that she herself was more concerned, because she was more routinely and regularly exposed to it." Moyers got calls from "Cabinet officers and others" who were "deeply concerned about his behavior." He noted that one day the President would be in severe depression. Then, "twenty-four hours later, no one who had seen him this way would ever have suspected it." LBJ would convince himself that he could win the war. Or the passage of a bill would "be an antidote." But when Johnson returned to the problems in Vietnam, the "cloud in his eyes" and the "predictably unpredictable behavior" would reappear.

Both Moyers and Richard Goodwin independently confided their worries about LBJ's mood swings to psychiatrists. As Goodwin recalled, one doctor told him that the President's "disintegration could continue...or recede, depending on the strength of Johnson's resistance and, more significantly, on the direction of...the war, the crumbling public support, whose pressures were dissolving Johnson's confidence in his ability to control events."

Stung by ridicule for ducking out of the Vietnam teach-in of May, McGeorge Bundy arranged to debate Professor Hans Morgenthau on television in late June. Once again he was defying the President's wishes. A furious LBJ told Moyers, "Bill, I want you to go to Bundy and tell him the President would be pleased, mighty pleased, to accept his resignation." Startled, Moyers did not reply. "That's the trouble with all you fellows," Johnson carped. "You're in bed with the Kennedys." Moyers lunched with Bundy to convey the President's annoyance with his debate and other speeches Bundy planned to deliver. Now he reports back to Johnson, who tells him that the real problem is that Bundy has been co-opted by the Kennedys.

MOYERS:He knew that he had...gone against the President's...wishes on these speeches. But he reiterated to me..."my honest understanding of the President's desire, stated three or four months ago, to make some speeches in the right way."...He...felt it was good to take some of the...criticism from the liberal community...away from the President and attach it to him...As best I could tell, Bundy was trying to say to me, "Look, if the President has any idea that anything's wrong with me...there's not...I'm very happy in my job."...

LBJ:You see, they [Robert Kennedy and his circle] would naturally talk to Bundy, and to Larry, and to Dick...That's where they would start. Then they'd take on...people...like Cater. Maybe Harry. They're kind of liberal and on the fringe, and not known as tied too closely [with me]. And then move in. I would imagine, though, that this started with Bundy. Because he's had to be sat down a time or two...The other day...he insisted on bringing up the Javits resolution. I said, "No, I'll think about that." He said, "We've got to decide it."...I just had to finally just really embarrass him and say,..."I told you two or three times, quit that! Let's go on to the agenda."...It was rather rough...You can see the crowd that's doing this. Bobby's going to Latin America now. He's got Gilpatric working for him. You saw the Gilpatric story in theNew York Timesthis morning. That's not accidental.

MOYERS:I saw that. Of course, I think there's a lot can be done with just more candidness. I think that's our basic problem, as I have mentioned to you before. Our image is due...primarily to their interpretation of our being overly secretive. I just think more candid and sincere discussion --

LBJ:And I just think you ought to say that -- on Jack's speech -- that you know that it's amusing to some of them that a man should have this affection for another man. But...if they will look at anyone who has been with me twenty-five years...John Connally...Walter Jenkins...all of them have this feeling. And that you have it. And that as far as this business of saying somebody's a "messenger boy," you just have never heard that. You have always given your honest opinion, and a good many times you've been vetoed. But...at thirty years old, you have made more big decisions that have been approved by the President than would have been approved if you had been working for AT&T.

MOYERS:Which is true.

LBJ:...Just say, "Now I know I'm not supposed to be a Sorensen, but Sorensen went much stronger than Jack [Valenti] did. He said that Kennedy was Christ." Compared him to Christ! But...they had a better feeling for Kennedy than they do [us]. And they've never liked Jack because they feel Jack is a personal servant of mine. And he is wonderful for me. He is not irritating to me. He's pleasant. He's soft. I think Buz is good for me. I think Harry is awfully good for me. I don't have men that clash with me? Marvin just says every day, "Mr. President, I don't think we ought to do this." But he does it in a nice, kind way.

ROBERT McNAMARA

Friday, July 2, 1965, 8:41 A.M.

Johnson must now decide among three main proposals for the American future in Vietnam. McNamara wants a serious escalation. George Ball wants to negotiate withdrawal. William Bundy is for "holding on" at present force levels but using American troops for more aggressive "search and destroy" missions, which, if successful, could lead to more U.S. ground troops. McGeorge Bundy wrote LBJ on July 1, "My hunch is that you will want to listen hard to George Ball and then reject his proposal. Discussion could then move to the narrow choice between my brother's choice and McNamara's. The decision between them should be made in about ten days."

LBJ:I'm pretty depressed reading all these proposals. They're tough, aren't they?

McNAMARA:They are...But we're at a point of a fairly tough decision, Mr. President...We purposely made no effort to compromise any of our views...

LBJ:Two or three things that I want you to explore. First, assuming we do everything we can, to the extent of our resources, can we really have any assurance that we win? I mean, assuming we have all the big bombers and all the powerful payloads and everything else, can the Vietcong come in and tear us up and continue this thing indefinitely, and never really bring it to an end?...Second,...can we really, without getting any further authority from the Congress, have...sufficient, overwhelming [domestic] support to...fight successfully?...You know the friend you talked to about the pause [Robert Kennedy]. You know the Mansfields. You know the Clarks. And those men carry a good deal of weight. And this fellow we talked to the other day here at lunch has a good deal of weight...He's got cancer, in my judgment. I've never told anybody, but I saw him yesterday coughing several times.

McNAMARA:He doesn't look good.

LBJ:He went home that very day and he hasn't been back since. Had a stomach upset. He can't carry on much for us. We have to rely on the younger crowd...The McGoverns and the Clarks and the other folks...If you don't ask them, I think you'd have a long debate about not having asked them, with this kind of a commitment. Even though there's some record behind us, we know ourselves, in our own conscience, that when we asked for this resolution, we had no intention of committing this many ground troops. We're doing so now, and we know it's going to be bad. And the question is, Do we just want to do it out on a limb by ourselves? I don't know whether those [Pentagon] men have ever [calculated] whether we can win with the kind of training we have, the kind of power, and...whether we can have a united support at home.

McNAMARA:...If we do go as far as my paper suggested, sending numbers of men out there, we ought to call up Reserves. You have authority to do that without additional legislation. But...almost surely, if we called up Reserves, you would want to go to the Congress to get additional authority...Yes, it also might lead to an extended debate and divisive statements. I think we could avoid that. I really think if we were to go to the Clarks and the McGoverns and the Churches and say to them, "Now, this is our situation. We cannot win with our existing commitment. We must increase it if we're going to win, and [with] this limited term that we define [and] limited way we define 'win,' it requires additional troops. Along with that approach, we are...continuing this political initiative to probe for a willingness to negotiate a reasonable settlement here. And we ask your support."...I think you'd get it...And that's a vehicle by which you both get the authority to call up the Reserves and also tie them into the whole program.

LBJ:That makes sense.

McNAMARA:I don't know that you want to go that far. I'm not pressing you to. It's my judgment you should, but my judgment may be in error here...

LBJ:Does Rusk generally agree with you?

McNAMARA:...He very definitely does. He's a hard-liner on this, in the sense that he doesn't want to give up South Vietnam under any circumstances. Even if it means going to general war. Now, he doesn't think we ought to go to general war. He thinks we ought to try to avoid it. But if that's what's required to hold South Vietnam, he would go to general war. He would say, as a footnote, "Military commanders always ask for all they need. For God's sakes, don't take what they request as an absolute, ironclad requirement." I don't disagree with that point...I do think...that this request for thirty-four U.S. battalions and ten non-U.S., a total of forty-four battalions, comes pretty close to the minimum requirement...

LBJ:When you put these people in and you really do go all out [and] you call up your Reserves and everything else, can you do anything to restore your communication and your railroads and your roads?...

McNAMARA:Yes, I think so...By the end of the year, we ought to have that railroad...and...the major highways opened...The problem is you can't send an engineering company into an area...unless you send combat troops with them. And we just don't have the combat troops to do that...

LBJ:What has happened out there in the last forty-eight hours? Looks like we killed six or seven hundred of them.

McNAMARA:Yeah, we killed a large number, I'd say, over the last three or four days...At least five hundred.

LBJ:...Can they continue losses like that?

McNAMARA:...Of the numbers that are killed by [U.S.] Air Force actions, and a great bulk of these people are killed that way, I would think that 75 percent are probably not from what we call the...guerrilla force.

DWIGHT EISENHOWER

Friday, July 2, 1965, 11:02 A.M.

LBJ:I'm having a meeting this morning with my top people...McNamara recommends really what Westmoreland and Wheeler do -- a quite expanded operation, and one that's really going to kick up some folks like Ford. He says that he doesn't want to use ground troops. He thinks we ought to do it by bombing. We can't even protect our bases without the ground troops, according to Westmoreland. And we've got all the Bobby Kennedys and the Mansfields and the Morses against it. But [Westmoreland] recommends an all-out operation. We don't know whether we can beat them with that or not. The State Department comes in and recommends a rather modified one through the monsoon season, to see how effective we are with our B-52 strikes and with our other strikes...Westmoreland has urged...about double what we've got there now. But if we do that, we've got to call up the Reserves and get authority from Congress...That will really serve notice that we're in a land operation over there. Now, I guess it's your view that we ought to do that. You don't think that we can just have a holding operation, from a military standpoint, do you?

EISENHOWER:...You've got to go along with your military advisers, because otherwise you are just going to continue to have these casualties indefinitely...My advice is, do what you have to do. I'm sorry that you have to go to the Congress...but I guess you would be calling up the Reserves.

LBJ:Yes, sir. We're out of them, you see...And if they move on other fronts, we'll have to increase our strength, too...[The State Department says] we ought to avoid bombing Hanoi until we can see through the monsoon season whether, with these forces there, we can make any progress...before we go out and execute everything. Of course, McNamara's people recommend taking all the harbors...Mining and blowing the hell out of it...They go all out. State Department people say they're taking too much chance on bringing China in and Russia in...They [want] to try...during the monsoon season to hold what [we've] got, and to really try to convince Russia that if she doesn't bring about some kind of understanding, we're going to have to give them the works. But they believe that she doesn't really want an all-out war.

EISENHOWER:...[For them to] agree to some kind of negotiation...[you must say,] "Hell, we're going to end this and win this thing...We don't intend to fail."...

LBJ:You think that we can really beat the Vietcong out there?

EISENHOWER:...This is the hardest thing [to decide,] because we can't finally find out how many of these Vietcong have been imported down there and how many of them are just rebels.

LBJ:We killed twenty-six thousand [Vietcong] this year...Three hundred yesterday...Two hundred and fifty of them the day before. But they just keep coming in from North Vietnam...How many they're going to pour in from China, I don't know...

EISENHOWER:...I would go ahead and...do it as quickly as I could.

LBJ:...You're the best chief of staff I've got...I've got to rely on you on this one.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

Saturday, July 3, 1965, Tape-recorded Diary

The family spent the long Independence Day weekend at the LBJ Ranch.

LADY BIRD:We helicoptered to the Coca-Cola Cove, where the big boat met us...Marianne [Means] put on a good demonstration of waterskiing...while I sunned and read...When the fast boat whirled past us, Lyndon had exactly the expression of a little boy aged two and a half sitting in the ice cream parlor chair -- a mischievous, happy, the-world-is-mine look.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

Monday, July 5, 1965, Tape-recorded Diary

LADY BIRD:Lyndon...is as proud of the new fast boat as Luci is of her green Sting Ray -- Took all of the pretty girls he could gather...for a ride...I [talked] to George Reedy about something serious and sad that worries me. He's having trouble with his feet. He will have to leave to have an operation...It has been excruciatingly painful for months...I flinched to think of George as a very old and kindly-natured bull in a pen, the daily object of the sharp darts of a host of rather brutal picadors...He feels like he's at his rope's end and will leave for this operation just as soon as Lyndon gives the go signal on [a new] press secretary. Lyndon had spoken about Bill Moyers...I think I do not remember three successive days at the ranch with such a minimum of calls from McNamara and McGeorge Bundy and Dean Rusk...Briefly the world has stopped to take a breath.

THURGOOD MARSHALL

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals

Wednesday, July 7, 1965, 1:30 P.M.

Johnson offers the job of Solicitor General to Judge Marshall, who famously championed school desegregation before the Supreme Court in the landmark 1954 caseBrown v. Board of Educationand succeeded in twenty-eight other cases before the Court. Without saying so flat-out, LBJ makes it clear that he intends one day to appoint Marshall as the first black Justice on the Supreme Court. (This he ultimately did in June 1966. When an aide later suggested another black judge, Leon Higginbotham, for the Court, Johnson glared and said, "The only two people who ever heard of Judge Higginbotham are you and his mama. When I appoint a nigger to the bench, I want everyone to know he's a nigger.")

LBJ:I want you to be my Solicitor General.

MARSHALL:Wow!

LBJ:Now, you lose a lot. You lose security, and you lose the freedom that you like, and you lose the philosophizing that you can do [on the Court of Appeals]...I want you to do it for two or three reasons. One, I want the top lawyer...representing me before the Supreme Court to be a Negro, and to be a damn good lawyer that's done it before...Number two, I think it will do a lot for our image abroad and at home...Number three, I want you to...be in the picture...I don't want to make any other commitments. I don't want to imply or bribe or mislead you, but I want you to have the training and experience of being there [at the Supreme Court] day after day...I think you ought to do it for the people of the world...And after you do it awhile, if there's not something better, which I would hope there would be,...there'll be security for you. Because I'm going to be here for quite a while.

MARSHALL:That's right, that's right.

LBJ:But I want to do this job that Lincoln started, and I want to do it the right way...I think you can see what I'm looking at. I want to be the first President that really goes all the way.

MARSHALL:I think it would be wonderful.

LBJ:...I want to do it on merit...Without regard to politics...I'm not looking for votes...I had [a margin of] 15 million. All I want to do is serve my term and do it well. But I also want...to leave my mark, and...see that justice is done. And you can be a symbol there that you can't ever be where you are.

MARSHALL:The answer is yes.

LBJ:Well, it's got to be!

* * *

LBJ:I've thought about it for weeks.

MARSHALL:I'm so appreciative to be able to help.

LBJ:Well, you can. Because you live such a life, and they've gone over you with a fine-tooth comb, and they could never use anything about you to thwart us, and we're on our way now.

MARSHALL:Wonderful!

LBJ:And we're going to move!

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

Wednesday, July 7, 1965, 8:05 P.M.

With a House vote on the voting rights bill just ahead, Dr. King is concerned about a substitute proposed by Republican Congressman William McCulloch of Ohio that, he fears, will dilute its effect. McCulloch's substitute would not enforce voting rights automatically. Federal action would require a complaint by twenty-five or more citizens in a voting district, possibly opening the way to local intimidation to keep blacks from voting. LBJ uses this opportunity to complain to King about his recent public criticism of Johnson's Vietnam policies.

KING:This McCulloch [proposal]...would stand in the way of everything we are trying to get in the voting bill...

LBJ:...We're confronted with the...problem that we've faced all through the years -- a combination of the South and the Republicans...How do we avoid this combination?...I've done the best I could. But they're hitting me on different sides, and the press is...[on] Vietnam or the Dominican Republic. Some mistake here or some mistake there. I'm getting kind of cut up a little bit. And Wilkins is having a national convention. And you're somewhere else. I called Meany to ask him to help and he'd gone to Europe...I called Joe Rauh and said, "For God's sakes, you try to get in here before it's too late."...They got a wire sent from Roy to all the Republicans. But the Republicans are...going to quit the Negroes. They will not let the Negro vote for them. Every time they get a chance to help out a little, they'll blow it...They could elect some good men in suburban districts and in cities. But they haven't got that much sense. That's why they are disintegrating as a party...

Now, when I went up with my message, I could have probably passed it by seventy-five. But [our situation in Congress] is deteriorating. The other day, they almost beat my rent subsidy, which is very important to...the poor people...Smith comes out and says my bill has had a lot of venom in it. I have a "great hatred for the South," and I'm like a "rattlesnake." I'm trying to "punish" them...So, he gets the Congressmen from the thirteen old Confederate states, and he [adds] a hundred [of them] with a hundred and fifty Republicans. That gives him two hundred and fifty...A good majority...

Unless we can pull some of the Republicans away, we're in trouble...Now the smart thing to do...would be to get some language that [will]...get this bill passed and start registering our people and get them ready to vote next year...You-all are either going to have confidence in me and in Katzenbach, or you ought to pick some leader you do [trust] and then follow [him]. I started out on this voting bill last November, right after the election...I called you down here and told you what I was going to do. I went before the Congress, made the speech, and asked them to work every weekend...They're getting tired of the heat from me. They don't like for me to be asking for rent one day and poverty the next day, and education the next day, and voting rights the next day. They know I can't defeat them out there in their district in Michigan and some other place.

So I'm just fighting the battle the best I can. I think I'll win it. But it's going to be close, and it's going to be dangerous...I cannot influence the Republicans. The people that can influence the Republicans are men like the local chapters of CORE or NAACP, or your group in New York...and these states where you've got a good many Negro voters. You've got to say to them, "We're not Democrats. We're going to vote for the man that gives us freedom. We don't give a damn whether it's Abraham Lincoln or Lyndon Johnson...We're smart enough to know, and we're here watching you. Now, we want to see how you...answer on that roll call."

* * *

LBJ:You ought to find out who you can trust...If you can't trust [me], why, trust Teddy Kennedy or whoever you want to trust...The trouble is, that fire's gone out. We've got to put some cedar back on it, and put a little coal oil on it...My recommendation would be that you...come in here and follow my political judgment and see if we can't get a bill passed.

KING:All right...Now there's one other point that I wanted to mention to you, because it has begun to concern me a great deal...In the last few days...I made a statement concerning the Vietnam situation...This in no way is an attempt to engage in a criticism of [your] policies...The press, unfortunately, lifted it out of context...I know the terrible burden and awesome responsibilities and decisions that you have to make...

LBJ:...I did see it. I was distressed...I'd welcome a chance to review with you my problems and our alternatives there. I not only know you have a right, I think you have a duty, as a minister and as a leader of millions of people, to give them a sense of purpose and direction...I've lost about 264 lives up to now And I could lose 265,000 mighty easy. I'm trying to keep those zeros down, and at the same time not trigger a conflagration that would be worse if we pulled out.

I can't stay there and do nothing. Unless I bomb, they'll run me out right quick...The only pressure we can put on is to try to hold them back as much as we can by taking their bridges out...[and] their ammunition dumps...[and] their radar stations...A good many people, including the military, think that's not near enough...I don't want to pull down the flag and come home running with my tail between my legs...On the other hand, I don't want to get us in a war with China and Russia. So, I've got a pretty tough problem. And I'm not all wise. I pray every night to get direction and judgment and leadership that permit me to do what's right...

KING:I certainly appreciate...your concern. It's true leadership and true greatness...I don't think I've had the chance to thank you for what I considered the greatest speech that any President has made on the question of civil rights...

LBJ:I'm having some new copies printed. I'll send you some of them...And I hope that you do talk to Roy [about the voting rights bill]. You-all see what can be done quick, because...this thing will be decided Thursday and Friday.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

Wednesday, July 7, 1965, Tape-recorded Diary

Lady Bird is spending most of the summer at the ranch while her husband stays in Washington. LBJ told one aide, "I don't like to sleep alone, ever since my heart attack." He feared that he would suffer another coronary and no one would be there to help. When Lady Bird was away, Johnson would ask friends, like his secretary Vicky McCammon and her husband, to stay the night in the First Lady's dressing room: "The only deal is you've got to leave your door open a crack so that if I holler, someone will hear me."

LADY BIRD:[Lynda] said something that brought a pang to my heart. She had been talking to her daddy. He sounded lonesome. She said, "You know, Mother, he's never the same without you."...She had called Jack Valenti...and asked about Lyndon. And he felt too that he was tense and lonesome. I feel selfish, as though I was insulating myself from pain and troubles down here. But I do know I need it.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

Thursday, July 8, 1965, Tape-recorded Diary

At St. Matthew's Cathedral in Washington, eighteen-year-old Luci Johnson has converted to Catholicism. Her parents and sister attended, but Lynda left the church in tears. Lady Bird "could not help but think we went in four and came out three." LBJ is indignant at Father James Montgomery, who gave Luci a "conditional" baptism, implying that her Episcopal baptism as an infant was invalid. He is also angry at Episcopalians like Bishop James Pike and Dean Francis Sayre of the Washington Cathedral, who have called Luci's decision an "insult" to their church. Leaving her husband at the White House, Lady Bird later flew back to the ranch.

LADY BIRD:He's hurt and angry at the Catholic Church. He thinks they've let her down. And he is hurt and angry too at the Episcopalians...No one is surprised Bishop Sayre took the occasion to preach a sermon...The gist was that she had done wrong...Anybody that hurts his little girl wounds Lyndon deeply...I called Luci, and I found, from her standpoint, that she had been consolinghim.She said, "But you know, that bad man didn't come home until twelve o'clock for dinner last night. But I was the best daughter I could be, and I tried to help him."...

Luci's self-confidence is shaken. She is almost hurt and frightened that she should have caused a rift, a disturbance, trouble for her parents...between any churches. Perhaps in part this will have a sobering effect on her, [and show her] that she can always trust her own judgment...She was also blissfully wide-eyed, happy, that she had had a message...from the Holy Father himself, welcoming her: "Tome,Mama,Luci-- just a little girl!"...Bishop Hannan...talked to Lyndon...[He will] issue a statement that the Church...[intended] no reflection on her previous baptism...Well, one can only go forward...So I tried to console and love.

I wish I could have been more use to Lyndon. He said, "Things are not going well here...Vietnam is getting worse every day. I have the choice to go in with great casualty lists or to get out with disgrace. It's like being in an airplane and I have to choose between crashing the plane or jumping out. I do not have a parachute."...When he is pierced, I bleed. It's a bad time all around.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

Saturday, July 10, 1965, Tape-recorded Diary

Johnson joins his wife at the ranch for the weekend.

LADY BIRD:About every ten minutes, Lyndon picked up the talking machine [in his car] to give Dale Malechek a job to do -- hinge off a gate here, a cow has got a cancer eye, put in a cattle guard there. Dale needs a stenographer's pad in his pocket when we are at home!...Lyndon...has every reason to feel fulfilled and proud this weekend. Last week the voting rights bill passed [the Senate] and the Medicare bill [passed the House] -- that impossible bill.

LADY BIRD JOHNSON

Sunday, July 11, 1965, Tape-recorded Diary

LADY BIRD:Lyndon talked to [Luci by telephone]. Then he handed the phone to me, saying, "I'll let your mother talk. She's like an old cow when her calf gets out. She just moos and bawls and looks around for her." If Lyndon has lost a certain something by the lack of the most polished Eastern education, he has the compensation at least of the earthy expressions, some so amusing, that really say what he thinks in a clear way...[I] said goodbye to Lyndon in his city clothes. I almost look upon them as fighting uniforms these days. And it is a little sad to say goodbye to him heading back to the city of troubles.

DEAN RUSK

Thursday, July 15, 1965, 9:12 A.M.

The previous day at noon, after a telephone call, LBJ walked into the office of his secretary Juanita Roberts and said, "Well, Adlai Stevenson just died." On a London street the UN Ambassador had suffered a heart attack, fallen backward, struck his skull on the sidewalk, and died. When Lady Bird heard the news at the ranch, she knew "how heavily this blow m

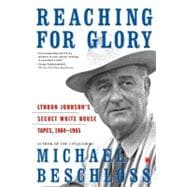

Excerpted from Reaching for Glory: Lyndon Johnson's Secret White House Tapes, 1964-1965 by Michael R. Beschloss

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.