| Acknowledgments | vi | ||||

| Introduction | xi | ||||

|

1 | (12) | |||

|

13 | (18) | |||

|

31 | (10) | |||

|

41 | (8) | |||

|

49 | (14) | |||

|

63 | (17) | |||

| Afterword | 80 | (3) | |||

| A Chronology of Woodrow Wilson's Life | 83 | (25) | |||

| Bibliography | 108 | (5) | |||

| Sources of Illustrations | 113 |

What is included with this book?

| Acknowledgments | vi | ||||

| Introduction | xi | ||||

|

1 | (12) | |||

|

13 | (18) | |||

|

31 | (10) | |||

|

41 | (8) | |||

|

49 | (14) | |||

|

63 | (17) | |||

| Afterword | 80 | (3) | |||

| A Chronology of Woodrow Wilson's Life | 83 | (25) | |||

| Bibliography | 108 | (5) | |||

| Sources of Illustrations | 113 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

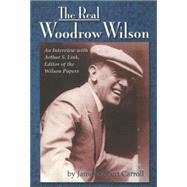

Chapter One

"LITTLE DID THEY KNOW:"

The Beginnings of the

Wilson Papers Project

CARROLL:How did you get interested in Wilson

originally?

LINK: I really wasn't interested in Wilson primarily. I was trained as a Southern historian at Chapel Hill, interested in twentieth century history -- this would be the late '30s, early '40s. And, of course, there wasn't much written about it.

My main interest at the time was the progressive movement in the South. In fact, if I may say so, I think I discovered it. Quite a very lively movement. Hardly different at all from Wisconsin and the Middle West. So I was searching about for a dissertation topic -- this was '41, '42, I was at the University of North Carolina -- and just at that moment the Wilson papers were opened to researchers. I think I was the second person to use them after Mr. [Ray Stannard] Baker, the official biographer, had finished. So I got terribly interested in the Democratic campaign of 1910 to 12. The Democratic Party was very much like today, transforming itself from an agrarian, populist party ... pretty much a bourbon-populist party, with conflicting traditions. [William Jennings] Bryan had announced in 1910 that he wasn't going to run for president in 1912 ...

CARROLL: At long last.

LINK: At long last, exactly -- after three tries. So this opened the field. And Wilson comes out, the governor of New Jersey. There really wasn't much on Wilson. We have Baker and we have [Joseph] Tumulty and the memoirs and things like that. But what fascinated me was, here's a man who is, I thought slightly mistakenly, who had been a pure academic. He'd been in academic affairs all his life, except for a brief, one-year try at law. Suddenly [he was] going as it were from the presidency of a small university [Princeton] to the presidency of the United States. How in the world could this happen?

I did my dissertation on the South and the Democratic campaign of 1910 to 12. This involved vast newspaper researches and as much manuscript research as one could do in those days, which wasn't a great deal. And I saw in the South a lively two-party system -- and a tremendous amount of support for Wilson. And that's really how I first got intrigued by this man.

I went to Columbia University in 1944-45. I was in Henry Steele Commager's seminar. And Commager was very interested in this subject. And I said I'd like to start a book on the political education of Woodrow Wilson. Which is what I did. I really started about 1909-1910, [Wilson's] entry into politics in New Jersey.

CARROLL: You were doing what at that time?

LINK: I did my doctoral work entirely backwards. I graduated with my [bachelor's degree] in 1941. I tried to get into the Navy and Air Force, but I couldn't do it. I thought I was going to be drafted. So I said, why don't I -- by that time I knew what I wanted to write my dissertation on -- at least get started on the dissertation. Then I got, not deferred, I got turned down. So I went ahead and wrote my Ph.D dissertation without taking any courses beyond the [master's degree], without taking my general examinations. One year, '43 or '44, I taught in the Army program at North Carolina State in Raleigh. That's when I studied for my generals, passed my generals, in 1944. I was ready to take my Ph.D, and they said: "But you haven't got enough course credits." So they said: "Why don't you go up to Columbia -- you've been here five, six years and you got everything we have to give you -- and go up for a year and take some courses and do your own work?" Which is what I did. In Commager's seminar I started this book. I did an enormous amount of newspaper research, particularly the coverage of the New Jersey period, the governorship, as well as the presidential campaign.

CARROLL: In those days, nothing was on microfiche?

LINK: Oh no, gracious me. I went through 325 newspapers for a two-year period. Just knocking it out on my typewriter. We didn't have Xerox back in those days. I was working twelve, fourteen hours a day in what we used to call the Annex of the Library of Congress, I think it's now called the Jefferson Building, right across the street from the old building. Anyhow, I finished this book.

Meanwhile, we had just moved to Princeton, in 1945, because I was appointed an instructor. I took my manuscript down to the then-director of the Princeton [University] Press, Davis Smith, Jr. He read it and was terribly excited and he said, "Look, Arthur, you've got the makings here of a wonderful first volume in a two-volume biography of Wilson. Why don't you add some chapters?" I had started some chapters covering his early life. "You could go through, as you do, the election of 1912, and then you could complete his life in one more volume." I said, "Fine, I'll be back." And I did. And that's how Wilson: The Road to the White House came out. So that was 1947.

CARROLL: Little did you know.

LINK: Little did I know. But I must say by that time I was really hooked on Wilson.

CARROLL: What intrigued you about Wilson: he was not as well known as people thought? Were you being surprised by him all the time?

LINK: It's hard to say what intrigued me most. So many things did intrigue me. Now mind you, I didn't know all that much about Wilson at this time. But I knew enough to realize I was dealing with a really first-class individual, a person of just unbelievable abilities, an obvious genius. A man of enormous oratorical ability, a marvelous writer, a great scholar. I guess there was a personal element, too. We were born about forty miles apart. I was born in Newmarket, Virginia. He was born in Staunton, Virginia, of course. We both came from similar backgrounds, ministerial backgrounds. My father was a minister. Wilson's father was a minister.... I think Wilson's integrity, his courage, and above all his extraordinary political skills intrigued me. As I say, at this point, I didn't know all that much about him, but I knew enough to think, "Well, here's a person really worth putting a lot of time into."

CARROLL: Did Ray Stannard Baker's eight-volume biography of Wilson [published from 1927 to 1939] seem kind of intimidating to you? I guess you were trying to bring something new to Wilson.

LINK: Yes. As you know, Baker's pretty much is a personal biography, not very deep in political or diplomatic history. I think it's a marvelous biography, the type that it is. But I'm primarily a historical biographer, really a historian. Baker was primarily a ... well, a journalist, if you'll pardon me. It was a journalistic type of biography. At that time, I really didn't have that much interest in Wilson personally. I was interested more in how he fit in in the context and history of the time. All that changed as I got to know him better and better. And I think The Road to the White House , once you get into the New Jersey politics, is a pretty good book. But I'm sure I would write it differently if I were ...

CARROLL: Really?

LINK: ... Oh indeed, I certainly would. I've got one excuse. When I started the work, the papers, the essential papers, of his early life, simply were not available. First of all, the correspondence between Wilson and his first wife were closed. Secondly, the correspondence with his lady friend, Mrs. Mary Ann Hulbert Peck, were closed. This was kind of a love affair. Not kind of. I guess he did have a love affair with her in 1908 to 1910. But most importantly, the Wilson papers to 1902 had not yet been discovered. So it's just as well I did not try to do the ... you know, I sketched out his career, analyzed his historical and political science writings, things like that.

CARROLL: But The Road to the White House was received very well. And as you got into the second volume, I guess you decided, "Well, we need more than this."

LINK: Exactly. That's right. Well, the problem was that The Road to the White House , particularly beginning about 1907, was written on such a level of detail, that to do this for a president of the United States obviously would require volumes. Which it did require: four more, up until 1917. I had no idea. I thought I'd do two volumes on Wilson. Well, I ended up doing five volumes and got it up to the First World War.

CARROLL: Did you stop there purposely?

LINK: I did not. I stopped there because I got sidetracked, I got derailed on the Wilson papers [publishing project]. In fact, they slightly overlapped. I published the last volume in the biography, Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace , in 1964. And by that time we were already heavily at work on the first [published] volume of the Wilson Papers. There was simply no way to do both. Plus, remember I was teaching full time over the period, having a very heavy load of graduate students. I had something like thirty-eight Ph. Ds during my career, and I was serving on departmental committees. I was very active in the profession ... I think I had that old Link energy. And I work pretty hard.

CARROLL: Would there have been one more volume or two more volumes in the Wilson biography after the five you completed?

LINK: There would have been at least four: two volumes on the war, hopefully only one volume on the Peace Conference, although maybe two, and one volume from 1919 to his death. Probably a ten-volume work.

CARROLL: Did you get started on some of those?

LINK: Not really. I have done a bit of article writing, incidental writing, on that later period, a good deal of it. Then other books.

Plus there's no way ... I'm getting to a point in my life where I can't go as I did around the world and working from a new source and spending ten years in Washington. I'm too old for that. Somebody will have to finish that.

CARROLL: How did you get involved [as editor of] the Wilson papers? Where were the papers, by the way?

LINK: What were thought to be the papers were in the Library of Congress. Wilson had willed them to the American people. They were to be deposited in the Library of Congress after Mr. Baker had finished with his biography.

CARROLL: Was Baker allowed to see everything?

LINK: Everything except the letters between the second Mrs. Wilson, I'll call her Edith, and Woodrow. I think he saw everything else. I mean he was allowed to see everything else. He couldn't see everything else by a long shot. There's more than one man could do.

CARROLL: More than he could do, not more than what you could do.

LINK: That's right. (Laughs.)

CARROLL: So what were thought to be the papers were at the library. They had been sealed by the family or what?

LINK: Actually, they were left to the Library of Congress. Mrs. Wilson was given the power to say when they should be opened. There was in fact an agreement between Woodrow Wilson and Baker before Wilson died that Baker should have first crack at them, which he did.

Now, I say "thought to be the papers." We'll get back to that.

You asked me about my relationship to the papers, how that got started. Nineteen fifty-six was the centennial year of Wilson's birth, as you know. And the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, which Franklin Roosevelt had helped organize in 1920, 1921, had never had enough money really to be a big mover in any field. They had held some conferences, made some grants and things like that. They led, sponsored the celebrations for Wilson's centennial. And the president of the foundation, Raymond B. Fosdick, was a student of Wilson's, class of 1905, at Princeton, a very close friend. And he was determined that the Woodrow Wilson Foundation with its rather small endowment in those days should devote its entire resources to getting out a fairly complete edition of Wilson's papers. And he's the one really who engineered and powered this whole movement.

So the Wilson Foundation board in 1958 voted to devote its entire resources to getting out a comprehensive edition of Woodrow Wilson's papers.

CARROLL: Little did they know.

LINK: Little did they know. And they appointed a committee to select an editor. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., was on it. August Heckscher [was vice chairman] and Philip C. Jessup were [some of] the people on it. [Other members included Fosdick as chairman, Jonathan Daniels, Harold W. Dodds, John B. Oakes, and Francis B. Sayre.] I don't mean to sound self-serving, but I was obviously by that time the one person who knew the materials, who had worked widely with the Wilson materials in that period. So they chose me as editor. I accepted.

CARROLL: How, exactly, did they ask?

LINK: I remember quite well. We met at the Century Club in New York in the spring of 1958. We talked about a lot of things and finally they said, "By the way, would you be willing to be editor of the papers?" Well, I knew there had been a lot of talk about this. And I accepted in one minute, I guess.

CARROLL: Then, little did you know.

LINK: (Laughs.) Little did I know. But I said, "Look, there is a problem." This was 1958. "I'm going to be Harnsworth Professor of American History at Oxford this coming fall for a year." "Oh, that's all right. That makes no difference at all. You can start in 1959."

Copyright © 2001 James Robert Carroll. All rights reserved.