|

xi | (2) | |||

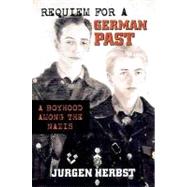

| Preface | xiii | ||||

|

3 | (24) | |||

|

27 | (21) | |||

|

48 | (19) | |||

|

67 | (14) | |||

|

81 | (20) | |||

|

101 | (17) | |||

|

118 | (10) | |||

|

128 | (13) | |||

|

141 | (12) | |||

|

153 | (9) | |||

|

162 | (11) | |||

|

173 | (12) | |||

|

185 | (9) | |||

|

194 | (11) | |||

|

205 | (10) | |||

|

215 | (7) | |||

|

222 | (9) | |||

| Appendix: Commencement Address, June 15, 1996 | 231 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

In My Father's House

When I think back to my childhood I see myself as an only child, accustomed from the beginning to play by myself in my room with my toy soldiers. My mother usually was busy in the kitchen or was reading a book in her sitting room. My father was away at work in the famous Duke August Library in Wolfenbüttel, my home town. On weekends he stayed home studying and writing in what we called the Herrenzimmer , the gentleman's study, which, in our apartment on the Harztorwall, served as our living room as well. I was used to my mother and my father working or reading by themselves alone. I thought everybody did that. So I never felt lonely or forsaken when I played by myself in my room. That was the natural way to spend one's time.

When my father was home on weekends he sat in our living room at his desk with books piled all around him. Sheets of white paper were everywhere, between pages and underneath the books. A shiny Continental portable typewriter stood in the middle. Every now and then, after much shuffling of papers and moving of books, he rattled on that machine for three to rive minutes, slid its carriage back everytime it pinged a signal, and pulled sheets of paper out at the top whenever he had filled them with rows of letters. The typewriter intrigued me. Though I was forbidden to touch it, I did take it out of its carrying case sometimes when my father was in the library and my mother had gone shopping. I rolled a sheet of paper into it from the top, and pecked at some keys to type my name or some other short word. I kept an ear out for the creaking of the garden gate to close up the typewriter the minute I heard my mother come home. But I was proud of myself that I had been a writer, even if for only a few minutes.

My mother, though, warned me that my father's work as a scholar was important. I was not to disturb him and ask him to play with me or tell stories about the war. If I wanted to talk to my father, she said, I had to wait until he was ready. So I often sat on the floor, underneath the big living room table, surrounded by some of my toy soldiers and railroad cars, which I had brought from my room in the hope that I might entice my father to play with me. Most of the time he paid no attention to me. Sometimes, however, he would turn around in his chair and look down at me, and I, hoping to snare him, would ask him a question. He usually shook his head, said, "No, no, not now," but then, a few minutes later, he would almost always look again, and I was ready.

I pretended there had been an accident on my railroad, a car had tipped over and spilled all the soldiers on the carpet. My father would get up from his desk, walk over, bend and sit down next to me on the rug. Then we fought battles, bombarded my toy soldiers with the pencil stubs my father used to carry in his vest pocket. We had trains collide and used a crane to set the cars back on the rails. That was great fun. I became very excited, so my father said that now the railroad workers had to take their lunch break and the soldiers had to pull back to rest, and we had to pause as well and wait for a while. When my mother then entered the room and saw us sitting on the floor, she smiled and shook her finger at my father. That was the signal for me to load my soldiers on the railroad cars and drive them across the hall into my playroom. I felt very happy.

Sometimes, instead of playing with my toy soldiers, my father would sit on the carpet with me and tell me of his life as a soldier during the Great War. He had joined up as a volunteer on the war's first day when he was nineteen years old, and had come back home on its last day as a lieutenant. He had been wounded and had a big hole in his upper back which I could see when I watched him shave in the morning. The hole was big enough for me to place my hand in it, though I never did that. And every now and then he would leave us for a weekend to serve with the reserves. When he sat on the carpet with me and spoke of the war he told of being hungry and thirsty and dirty and lonely, and of the enemy shooting at him. I asked him whether he had not been afraid. He said no, a soldier was not afraid. A soldier had his comrades who stood by him and comforted him. He had his sweetheart to think of at night and songs to sing to her:

Not I alone, did sing my song,

Annemarie,

T'was all of us who sang your song,

We of the company.

And my father would hum the refrain. It sounded very sad. It made me think of my mother, because her name was Annemarie too. It never occurred to me then that my father could not have known her during the war. But I imagined her in another song my father sang:

In the rose garden

I shall wait for you.

When the clover is green,

or the snow lies white.

To me as a six- or seven-year-old, this was my father, the soldier, the brave man who suffered and fought for his country and who loved his sweetheart whom he missed. I took in his words of comradeship, of loyalty, of bravery, and of love for people and country. It seemed to me if I, later in life, only could be like him, both a scholar and a soldier, I could not ask for more. I was very proud of him, the scholar and the soldier, the Gelehrte and the Soldat or, perhaps more exactly, the scholar-soldier. To me as a boy there was no contradiction between the two. I thought my father perfectly illustrated the combination. I was determined to follow in his footsteps. And so, early in my life, I began to think of a career among books and arms, scholars and warriors, among men who were quiet and studious, but also strong and brave. I thought of my future self as a man who took, combined, and preserved the best of his home, his family, and his country; a man who was, for his students and his soldiers, an inspiring model to follow.

Today, three scores and some years later, I still think of my father as the scholar and the soldier, though I wonder whether he had chosen the life of the scholar-soldier or whether he was the scholar whose lot it was to serve as a soldier in two wars, and loose his life in the second. I look at his portrait that hangs on the wall above my desk. It is drawn with colored pencils and shows the left side of my father's face as he gazes pensively through his glasses into a distance that cannot be seen. I do not know what he is looking at. I doubt that he is looking at anything. His eyes, rather than focusing on an object, invite me to join him in contemplating a problem, a riddle, a mystery. It is a look I well remember when I, as a little boy, asked him a question and he would take his time to search for words that I could understand. However, in the picture, it is answers for himself for which he seems to search. The father I remember as the scholar, the Gelehrte , had dedicated his life to the search for answers.

The picture, however, in its realism of time and place, portrays him as a soldier in his officer's tunic with his rank insignia and the number "17" of the Braunschweig infantry regiment on his shoulder. The soldier who drew the sketch added the initials "HB," the date "29.4. 1943," and as identification of my father, "scholar of peasant ancestry." A year later he added a few more words, as an afterthought, perhaps, or, more likely, as a mourner's lament: "My good captain and friend, Dr. Herbst, [SYMBOL OMITTED] 17.8.44 in Nisch/Serbia."

When the picture reached my mother and me in the waning days of 1944 I was about to begin my own career as a soldier. I then asked myself, was I really to follow in my father's footsteps? Was that his bequest to me, the life of a scholar and a soldier? Was that what he wanted me to do? There was little time to weigh such questions. The war pressed in on us from all sides and I did not know for certain how to answer, though I told myself, perhaps to drown out my own doubts, that that was indeed my father's legacy for me. I asked my mother what she thought about my father's life as a scholar and a soldier. Did he endorse that double role? Would he have chosen it if wars had not determined his steps? Through her tears she said only: "He was a scholar and he served his country; he had no choice."

Perhaps, I thought, I shall have no choice either.

But when I was still a little boy I thought that as a grown-up I would want to work just like my father, sitting behind a big desk, surrounded by books, and read and write. I knew that what my father did was called research, and I knew also that both he and my mother were never without books. In our living room, my father's room, just to the right of his desk stood the big Bücherschrank , its glassed-in midsection showing off leather-bound novels of World War I, books by Edwin Dwinger and Werner Beumelburg that later, when I was in my teens and had learned about the war from Bodo Wacker, my German teacher in the Große Schule , I hungrily devoured. There were many smaller volumes of church history and philosophy and others that dealt with books and their bindings, some of them written by my father. I did not find those titles very interesting, though I felt I should at least leaf through them to find out what my father's work was all about. To the right and left of the center glass door, wooden doors could be opened behind which stood row on row of cardboard file boxes, some of them crammed full with envelopes holding little paper slips with names and numbers scribbled in my father's handwriting, and others stuffed with blank postalcards that, too, bore strange notations. Some of the shelves were full of clippings from newspapers and magazines and what my father called Sonderdrucke , special reprints of articles and essays he or one of his colleagues had written. But that was not all. There were three more bookcases in the Herrenzimmer . One was black and reached to the ceiling. It loomed between the two windows that looked out on the park in front of the apartment. It was filled with history and art books and editions of the collected works of authors like Goethe, Schiller, Uhland, Hauff, and others. Another shelf, brown and half as high and placed next to the entrance door, was crammed with paperbacks. Finally, in front of the tall, white tile stove in the room's corner, stood a small brown shelf with the many volumes of Meyer's Konservations Lexikon , a treasure trove for me once I had mastered the art of reading and could find answers there to questions like What is a vagina? and What does it look like?, questions that I did not want to ask my mother or my father.

We had moved to the apartment on the Harztorwall when I was six years old and became a pupil in the primary school on the Karlstraße. Books, those that I needed for school and those that encircled my parents' living room, became very much part of my own little world. They surrounded me and followed me everywhere, at home and in school. They were favored presents at birthdays and at Christmas time, and, once I had learned how to read, they also began to crowd every available space in my playroom. I literally disappeared among books when, as I sometimes did, I visited my father in the Duke August Library. He was usually too busy to pay me much attention but he did not mind if I wandered off into what was called "the magazine." That was fine with me, and I was never happier than when I could vanish in the stacks among the miles of metal shelves with their books neatly lined up. I followed the spiraling iron stairs up and down, from under the roof of the huge building to the basement with its dark and dusty storerooms. I soon selected my favorite hiding places where I would sit on some empty shelf space and leaf through dusty parchments, fascinated by their sometimes brightly colored and sometimes somberly darkened and musty pages, mystified by their gothic letters and Latin text, but always prompted to keep on looking for something new, something unexpected, something that would make me famous as discoverer--famous as I had heard people say my father was, because he had there found manuscripts previously thought lost or nonexistent.

My admiration for the soldierly life, actually, had begun even before I listened to my father telling me about the Great War and to Bodo Wacker's narratives in my high school classroom. It had been stimulated even before I read the novels by Edwin Dwinger and Werner Beumelburg. It began when I was three years old and we still lived in the last house at the edge of town where the Kleine Breite (the Little Broad Road) ended as it met the Jahnstraße. The Jahnstraße was named after Turnvater Jahn, the father of the German "Turners" who, a hundred years before I was born, had taught that gymnastics and clean, healthy living would lead to a strong and vigorous Germany. The Jahnstraße ran along the training grounds of the Reichswehr, the German army of the 1920s and early '30s. The grounds stretched for miles up to and beyond the horizon. I could look across them from the window of my room in the house on the Kleine Breite. That is how I came to know something about the soldiers of the Reichswehr. I saw the troops often, right out of my window. The soldiers clad in their field gray uniforms rode in their cars and trucks across the expanse to the east of our house, pulling their cannons behind them and, sometimes, fighting mock battles, with lots of smoke blowing around the hilltop that overlooked the training ground. I was fascinated by what I saw and I tried to recreate these scenes in my playroom. In a wooden toy truck and metal toy staff car I carted my companies and battalions of plastic soldiers to their positions and led them to victorious combat. I spent hours, mornings and afternoons, in my solitary war games and rarely ran out of ideas about how to arrange and vary the scenes of battle. I lived and dreamt soldiering.

My father often took me out on the training ground for a walk at supper time, and then we marched across the grassy plain and hills. My parents had discovered that I, who was a notoriously bad eater, would munch almost anything as long as I could trot along, beat my drum, and pretend to be a soldier. It was then, too, that I learned from my father how to estimate distances, take cover, and deploy my troops who, we pretended, followed us in company strength. My father acted as my military advisor. Often, on days when the sun was shining, I used to ride on my tricycle on the Jahnstraße at noon time, peering down the asphalt ribbon anxiously, looking for the little black dot in the distance that, as it came nearer, slowly grew in size until it was big enough for me to know it was my father who came home for lunch on his bicycle. I could hardly wait to tell him what I had seen on the training ground through my window or what battle scenes I had arranged with my toy soldiers in my room, and I wanted his advice as a company commander. After all, he had been a soldier in the Great War. What better advice could I get? I wanted to be a soldier like him. Soldiering was something I thought I would do all my life.

It was Gerhard, my mother's brother, who lived with my grandparents in far-off Chemnitz, and who often visited us on the Kleine Breite, who introduced me to another kind of soldier than the one I knew from my father and from the Reichswehr I had observed out of my window. Uncle Gerhard usually came at Christmas time when my father and I had unpacked my windup railroad that ran on tracks that were so big they took up the whole floor of my room. I was three years old then, and I know that for sure, because my mother told me later that my uncle had come in 1931, the thirteenth year of the Weimar Republic of whose existence I was then blissfully unaware. Uncle Gerhard did not like the Weimar Republic. He said so several times, because, he said, thirteen horrible years were enough, what with inflation after the Great War when there was never enough money to buy food and clothing, the moral filth in the big cities, and the incompetence of the politicians. Young people like myself, he said, had to be ready to lead our fatherland out of its miserable state.

I wasn't quite sure what moral filth was and why and how politicians were incompetent--or, for that matter, what incompetent meant. But I had heard enough about inflation from my mother to know that it made our money worthless. My mother had told me more than once, how, as a student, she had rushed out early in the morning when the shops opened to buy a head of cabbage for one million marks, afraid that if she was late or had to stand in line for an hour or so, the price would have gone up to a million and a half.

I could only guess what my uncle meant when he spoke about moral filth in the big cities and about incompetent politicians. I was going to look for that filth when we went to Braunschweig, the big city near Wolfenbüttel, right after Christmas day. My mother wanted to shop there at the year-end sales. She, Uncle Gerhard, and I boarded the streetcar and rumbled along in the old creaky wagons through the Lechlum Woods, which stretched to the north of Wolfenbüttel, and then continued through the villages and open fields. In Braunschweig we walked past the store windows and looked at the mannequins who showed off pretty dresses for women and green loden coats for men. I didn't see any filth there. But then we heard music, fifes and drums, and singing. There were men marching in brown uniforms, carrying a red flag with white and black markings. People on the sidewalk next to us stopped. Some waved and applauded, others whistled and booed.

"These men in their smart uniforms," Uncle Gerhard said, "are our hope. They will do away with the filth, decay, and incompetence."

"How will they do that?" I asked, and my uncle replied: "They are soldiers for a new Germany. They'll bring us better days."

"But they don't wear a soldier's uniform," I said. "Their shirts are brown," and I looked at my mother because she had remained silent and shook her head.

"Well, Jurgen," she said, "these are a different kind of soldiers than your father was. Besides," she added, "your Uncle Gerhard and your father and I don't always agree. But it is true, we don't like filth and incompetence either."

I still didn't know what filth and incompetence meant but I sensed that, whatever they were, when both my parents and uncle disliked them so, they must be bad. And soldiers, even though they wore brown and not gray uniforms like the Reichswehr, were supposed to fight everything evil and harmful. So, perhaps my uncle was right also in his approval of the marching men.

Still, one thing puzzled me. Wherever I had seen soldiers, real soldiers in field gray uniforms, and wherever I had heard people talk about soldiers--my father and, later, after I had entered the Große Schule , my teacher, Bodo Wacker--people applauded and said good things about them. But here in Braunschweig, where the soldiers wore brown uniforms, some people hissed and booed. How could they do that, I wondered, if the men they booed were soldiers? They were a different kind of soldiers, my mother had said. Just how different were they?

I trusted my mother and what she said. She, too, knew about soldiering, and she, too, like my father, was, in a manner of speaking, a veteran of the Great War. Five years younger than my father, she had lived through the terrible winters of 1917 and 1918 in Chemnitz with her family, my grandfather Felix and grandmother Alma, her sister Mausi and my uncle Gerhard. She was a teenager then, and had been cold and hungry. She had subsisted on a diet of boiled turnips and cabbage with frozen potatoes and no meat or fat to speak of. I heard her remark once that instead of monuments with soldiers on horseback brandishing drawn swords we should just have a big turnip, cast in stone, erected in our marketplaces. That would be a more fitting memorial to the suffering of the children and women during the war. Her health suffered permanent damage; an anemic condition and stomach upsets remained with her for the rest of her life. In 1919 she entered the University of Rostock on the Baltic Sea as a student of German literature. In the following year, she decided to transfer to the University of Leipzig in Saxony. It was there that she met my father.

My father was the first member of his family who attended a university, and only the second who entered a white-collar career. His family roots went back to the agricultural lands of the Ruhr valley. From the late 1700s on, his ancestors had been weavers and tailors, carpenters and blacksmiths, teamsters and foundry workers. The first white-collar worker among them was my father's father, born in 1865, of whom I remember nothing. He made his living as a postmaster, moving from the Rhineland, where my father was born in Düsseldorf, to Delitzsch, a small town in rural Saxony near Leipzig. From there my father came to the university.

My mother's family, just as my father's, were rural folks. They traced their ancestry back to Lutheran ministers and soldiers to the generation of my mother's grandparents. From what little we know of earlier times, a judge, a local official, a shoemaker, and their wives and children were among them and had resided in rural areas of Saxony and Thuringia. During or shortly before the Great War my grandparents with their two daughters and one son moved to Chemnitz, the city that was thirty years later to become Karl Marx Stadt in the communist German Democratic Republic.

In Leipzig my parents met for the first time. My father studied history and, in the center of the German book publishing trade, immersed himself in the bibliophile's specialties of bibliography, the craft of bookbinding and its literature, and what we today would call library science. My mother, working for a doctorate in German literature and, like my father, stimulated by the Leipzig environment, planned to enter the publishing industry. I never found out what it was that made her give up, just short of reaching her goal, her plans to obtain a degree. Whether it was the financial difficulties created by the inflation, the urgings of my father--a possibility that, knowing his unconventional attitude as a person who believed strongly in the equality of the sexes, I have always discarded--or the possibility that my mother simply decided that she would find an outlet for her literary interests at my father's side and did not need the doctorate, I cannot say. But when, in 1924, just after the worst of the inflation had passed, my father submitted his dissertation and received an invitation to start work at the Duke August Library in Wolfenbüttel, my parents decided to leave Leipzig, set their wedding day, and prepared their move to the little North German town.

In Wolfenbüttel, the former residence of the Dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, the library's famed collections of Bibles, maps, and incunabula, unmatched anywhere in Europe, promised a fertile field of research for my father. The city's literary reputation proved to be of special attraction to my mother. Wolfenbüttel had been the one-time home of the philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and of the playwright Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. When Lessing during the last decade of his life presided over the Wolfenbüttel library he wrote there two of his most memorable dramas, Emilia Galotti and Nathan the Wise , the latter one of the German language's most powerful pleas for toleration and humanity. Wolfenbüttel, too, had been home to the young Wilhelm Raabe from whose pen flowed a series of short stories and novels that I would read with fascination during my high school days. And it was to Wolfenbüttel where the humorist Wilhelm Busch, the creator of the Max and Moritz stories, which later were to provide the model for the Katzenjammer Kids, came on frequent visits and spent many of his vacations. Given ail these incentives and attractions, the additional fact that Wolfenbüttel promoted itself as a city of gardens and schools made it ever more persuasive to my parents to accept the invitation. No doubt, too, they were thinking of the children they might have and of the schools these children would attend. I, of course, not having been conceived, never mind born as yet, was not consulted how I might feel about Wolfenbüttel's schools. In retrospect, though, I could only be grateful to my parents for the town and the schools they had picked for me.

So, having made their decision, my parents were married by my grandfather Felix on May 30, 1925, in the Church of the Cross in Chemnitz, Saxony. Everyone present there, I was told later in a cherished family tale, knew what had happened when my mother came home to Chemnitz from Leipzig to ask her father for permission to break off her studies and marry my father. Grandfather Felix looked at her disbelievingly and then exclaimed: "You fool, all that work for nothing!" and gave her his blessing.

From my third year to my sixth the memories of my home on the Kleine Breite in Wolfenbüttel and of my grandparents' apartment in Chemnitz provided the two geographical poles of my existence. I looked forward each year to summer vacation when my parents and I embarked on the long train ride from Wolfenbüttel to Chemnitz. We used to stop over between trains in Leipzig where my Uncle Paul, my father's brother, and his wife, Tante Mieze, with their two daughters, Bärbel and Ursel, would await us on the platform and accompany us as we switched trains in that huge station. It seems that no one in that group ever forgot how my teddy bear rode in my backpack and made people laugh and wave at us as we marched from one platform to another. I heard that story from my Leipzig relatives decades later again and again.

Chemnitz itself struck me, even as a little boy, as a rather unappealing city, the soot from its factories filling the air and covering every inch of space outside. While in Chemnitz I had to wash my hair every night and carefully wipe the black dust away from my eyes and out of my ears. I did not like that. But there were nice woods at the outskirts of the city where we went whenever we could to escape the dirt, feed the squirrels, and follow the many walking paths that inevitably ended up at a restaurant where we sat down for coffee, cake, and whipped cream, a ritual that, after the worst of the depression had passed and, as my Uncle Gerhard said, Adolf Hitler had made us human beings again, we never omitted. It was something I liked very much, though Uncle Gerhard, who had his bachelor apartment in Chemnitz, always warned me that, while the cake and whipped cream were allright, I should watch the peanuts. If I continued to munch them as I did instead of feeding them to the squirrels, I would turn into a squirrel myself.

One of the great attractions for me in Chemnitz was Grandmother Alma's cooking. She had a wonderful knack of serving Saxon specialties, such as a soup made of blood sausage with egg whites floating in the broth or a pancake-like concoction called Quarkkeulchen . These were fried of eggs and a curdy cream cheese and then smothered with cooked prunes. Even though I was not a hearty eater, I had my favorites. I loved dumplings made of yeast and served with stewed cherries and, even more, dumplings made of potatoes and served with any kind of roast and some vegetable like cauliflower, brussel sprouts, or kale. Meal times in Chemnitz were something to look forward to, and I always was on my best behavior. I would never have risked angering Grandfather Felix or Grandmother Alma and being sent away from the table. The food was just too good.

By the time I was six and arrived for the vacation, my first cousin had just been born to Aunt Mausi and her husband, Uncle Heini, who also lived in Chemnitz. It became my task to push the baby carriage, and I took great pride in playing "protector" of the little girl. Uncle Gerhard, however, would have none of that. I was a boy, he said, not a baby's maid, and I was growing up to be a soldier. So he gave me a red flag on a black pole, with a swastika in the middle of a white field, put his old steel helmet of the Great War on my head, and urged me to march ahead of the rest of the family on our wanderings through the woods. I wasn't sure I really liked that because I was fond of pushing the baby carriage. That was a real task, I thought, whereas marching ahead with flag and helmet was just make-believe. Besides, the helmet really was too big and heavy and it made my head hurt. So I was very glad when Grandmother Alma and my mother intervened. Aunt Mausi rolled up the flag and placed it and the helmet at the foot of the baby carriage, and asked me to push the carriage again. Thereafter, we left helmet and flag at home.

At my grandparents' apartment I played railroad or streetcar. The carpet in the living room had all sorts of intricately snaking lines that made for a great network of pretend rails on which I moved the wooden blocks from a construction set. Uncle Gerhard approved of that. In fact, at one Christmas after my sixth birthday, he gave me a beautiful silvery train to add to my railroad at home. It was the "Flying Zeppelin," with a rotating propeller at its end. From then on, Uncle Gerhard could do no wrong. By that time, too, the Weimar Republic was no more, and the soldiers in their brown uniforms had become a familiar sight on the streets. Uncle Gerhard, who himself wore such a shirt at times, no longer spoke about filth and incompetence, but he also didn't seem to be very happy when he wore his brown uniform. "The damn thing," he said, "takes too much of my time." He didn't exactly explain what the "damn thing" was. Grandfather Felix said he should watch his mouth when he spoke in his house.

I thought all of that a bit strange. When I asked my uncle whether he didn't like to be a soldier, he replied only that the men in the brown shirts were not "real" soldiers, after ail. I felt vaguely reassured because I hadn't forgotten my mother's remark in Braunschweig that the brown-shirted soldiers were different from my father's kind of soldiers. "Real" soldiers, I was now all the more convinced, wore field gray, not brown, uniforms. That was why, a few years later in Wolfenbüttel, I was bitterly disappointed when an anti-aircraft regiment moved into the city's army barracks. In their blue air force uniforms I could not quite accept these soldiers as "real" either.

Without clearly realizing it at the time, in my childhood years I had been steeped in the traditions of German Wissenschaft , of the Prussian-German army, and, through my grandparents in Chemnitz, of Lutheran Protestant Christianity. Loyalty, courage, steadfastness, faithfulness, righteousness, and love of God, country, family, and friends --these were the virtues I had been taught to live by. They made up an inheritance that in my childhood and early manhood years appeared immensely attractive to me and that, despite the growing intensity of the war that would engulf me in my teens and despite the revelations of its horrors, still proved, until very nearly the end of my life in Germany, the rock on which I believed I could stand and survive.

Above all, it was the picture that I, as a child, had built up of my father that embodied for me that inheritance and that sustained my determination to create a life in his image for myself. He was to be my model. I could not tolerate the slightest doubt in his right and righteousness. Any such doubt would have undermined my sense of selfhood and destiny.

Thus it was that, later in life, as my childhood lay in the past and I lived in another country, a sense of unreality overcame me when I listened to others talk about their fathers. I heard friends speak of an ambivalence they harbored toward their fathers, an ambivalence that had arisen out of conflicting emotions of love and anger and that had persisted into their adult lives. My friends remembered their fathers as protectors whose love they had not earned and as disciplinarians whose anger they had not deserved. They remembered their own inability to understand what they took to be the contrariness in their fathers' manifestations of love and anger and their own confused reactions. They felt resentful because they could not see how they had earned such treatment from their fathers, and they felt guilty because they also seemed to think that they somehow deserved it. As a result their memories of their fathers were tinged with ambivalence, an ambivalence that shifted uneasily between expressions of love and outbursts of anger.

I did not understand what my friends were talking about. I thought I knew of no ambivalence in my feelings toward my father, had never felt that I could not understand his behavior, and did not share my friends' resentment and guilt. My father had never left me in doubt about his love. When I had disappointed him and he had disciplined me, I had accepted his sorrow as justified and his punishment as just. It was another token of his love. I had been disturbed only that I had given him occasion to be sad and angry and that I had failed to live up to his expectations. My father, I used to tell my friends and myself, could have done no wrong. For me he had always been a tower of strength and righteousness: the quiet, serious scholar, loved by myself and my mother, and the loyal, incorruptible officer, revered by his comrades and soldiers.

As time went on, however, my sense of unreality led me to question whether I was so different from my other friends after all and whether I did not secretly harbor ambivalent feelings toward my father. Had his path through life been as straight and uncomplicated as I thought it had been? Had I never been puzzled and unsatisfied when he responded to my questions and I listened to his explanations? When I pondered what my friends and acquaintances had said and when I tried to place what I knew about my father into the circumstances of his life, there were parts that did not seem to fit so easily and smoothly as I had thought.

I remember asking him early on, when he was still at home and working in the library, why, when we visited in Chemnitz, Uncle Gerhard sometimes wore the brown shirt of the SA, the storm troopers of the Nazi party. My father said only that Uncle Gerhard had his reasons, and each one of us would have to decide for himself what was best.

I was all the more puzzled about his answer when some time later my mother and my grandfather told me that my father steadfastly refused to join the SA and the Nazi party and thus had excluded himself from any chance of becoming the director of the Duke August Library. To become a party member and thereby to declare his loyalty to the Hitler government was a step the party expected everyone to take who aspired to any elevated position in the civil service. So why would my father refuse to join and yet not appear to mind that Uncle Gerhard wore the brown shirt? By the time I heard of this I could no longer ask my father because the war had begun and he had left home to be a soldier again. When I asked my mother about it, she, too, said only my father could explain that, but, she added, he had done the right thing.

When I was twelve and my father came home on his first leave from the war I had other, more pressing, questions to ask him. I wanted to know why the Führer, two years ago, had himself assumed control of the army and had dismissed several generals. My father said only that good soldiers do not question their superiors. I, seeing myself as the son of an officer and a future soldier, accepted that answer and did not think it right to ask further questions. But I still felt uncomfortable with the idea that the Führer, who had not been trained as an officer and had not risen through the ranks, could dismiss soldiers, even generals, from their posts. That did not seem right to me, and I really wanted to know how that was possible.

But then I asked my father to go out with me wearing his uniform and the service medal he had been awarded. I wanted to show him off to my friends. But my father refused. He was glad, he said, being home, to wear his civilian clothes. Besides, he said, we were going to church together on Sunday to listen to Propst Rosenkranz preach at St. Mary's. We could meet my friends there. But that wasn't the same, I thought, as an afternoon stroll down the Lange Herzogstraße, Wolfenbüttel's main business street. Few of my friends came to church, and my father would not be in his uniform. I just could not understand him. What better clothes could there be than an officer's army uniform? I was quite disappointed. My father's refusal did not fit my image of him as a proud soldier.

The next year, when I was thirteen and Germany had been at war for two years, my father came home on leave again and remarked that the time might come that I would have to enlist in the armed forces. What branch did I have in mind? he asked. Though I had always thought of volunteering for an army officer's career I was not ready to say so. Perhaps it was my lingering unhappiness with my father's refusal to go out with me in his uniform or with his unwillingness to answer my question about the dismissal of the generals that made me hesitate. At any rate, I responded somewhat truculently that, wanting to belong to the very best unit there was, I was considering joining the Armed SS, the party's military fighting units.

Among us boys, soldiers of the Armed SS, portrayed by the Nazis as combining the most desirable qualities of army and party, represented an ideal that both fascinated and awed us. We had very few personal acquaintances who actually belonged, and most of us boys seemed to feel more comfortable with soldiers of the regular army, air force, or navy. But when my father asked me I blurted out my answer as though to spite him and myself.

I was not prepared for my father's reaction. There was nothing of the quiet earnest scholar or the resolved conscientious soldier about him when, his face turning a purplish red, his veins standing out in his throat and neck, he shouted at me so that it seemed it could be heard miles away: "Never, never will you ever join the Armed SS. You can do anything you like with your life, but you will not, never, under any circumstances, join the SS. Do I make myself clear? Do you understand that?"

I was far too taken aback to give any coherent response or to ask why not. I had never before seen my father in such a state of furious anger. I could only mumble, "Yes, yes," and withdraw into my room. I was not disposed to ever raise that issue again, and I could only wonder what it was that had provoked such an outburst.

When my father had departed again for his unit I asked my mother why he had been so angry. She only shook her head and said that she thought she knew, but that it was best not to talk about it and that he had been right in his telling me never to even think of joining the SS.

When, in later years, I thought about these instances and tried to reconstruct for myself the probable causes of my father's outburst and of his refusal to explain why he had not answered my questions, I wondered whether there had not been more than one reason. After all, he was serving in Poland and, as a railroad transport officer, he must have seen the trains carrying their human cargo to the concentration camps at Auschwitz and elsewhere. Did he want to protect me from the knowledge of evil? Was he afraid that he might disillusion my faith in my country? Did he realize that, had he told me what he knew and feared, there was the very real risk that an incautious word of mine would expose me, my mother, and himself to arrest, deportation, and incarceration? These, I thought, were reasons enough to have sealed his lips.

And yet, I could not rid myself of the thought that, notwithstanding the probable reasons for his silence, I would have wanted him to share the doubts and ambivalences in his life. It would have helped me to better deal with the questions that were to come and disturb me. But, thinking of how difficult it had always been for me to face ambivalence, I could not help wonder whether, had he even wanted to share and explain, he would have been able to do so.

But even more so I wondered why for so long I had fervently resisted questioning the belief in my father's righteousness and infallibility. At first I surmised that I had done so simply because, for all practical purposes, my memories of him extended only to the first eleven years of my life. Then he had left at the beginning of the war, and I had seen him thereafter only for at most two weeks a year. I could not bear, I told myself, to destroy my happy childhood recollections of him. They were uncomplicated and comforting, and I wanted to keep them thus. At the same time, I dimly realized that by holding fast to an unblemished picture of my father, I, who strove so much to be like him, could escape ambivalence and doubts in my own life. But the more I thought about it, the more I began to suspect that, while partly true, that surmise could not fully explain my reluctance to probe into the ambiguities of his life and into my relationship with him.

After all, my memories of him did not end in 1939. After that year until his death in 1944 I not only saw him every year when he was on leave, I also received many letters from him. It was during these leaves and through the letters that I learned to my dismay that, far from leading the life I thought my father wanted me to live, I had often disappointed him. He let me know, not always justly, I thought, of his disapproval and censure. When I finally admitted these instances to myself, I realized that my relationship to him had not been as unperturbed and free of conflict as I had persuaded myself to believe. I had known resentment and guilt.

(Continues...)