Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

We were broke. The Clash then had no manager and were lurching from one financial crisis to the next. The band was recording London Calling at Wessex Studios, although the crisis of confidence between record label CBS and the Clash was so deep that no one was sure if the record would ever be released.

Joe Strummer, Mick Jones and Paul Simonon had no money. Topper Headon certainly had none. Neither had I or the Baker, who between us shared in all the band's decisions, did all of the Clash's administrative tasks and lugged around and set up the amps and PA. CBS was trying to soften the Clash -- toning down the band's image and its political stance -- by withholding money. The last-minute offer to appear at a music festival in Finland was a chance to earn some cash which was too good to miss.

But it had to be cash. We owed money to banks, and all accounts had been frozen pending a deal with former manager Bernie Rhodes. The Clash's appearance at the Russrock Festival, Finland, had been set up by Ian Flooks. He had recently set up his own agency, Wasted Talent, and was touting for trade, with a watchful eye on the managerless Clash. I had to impress on him that we were not interested in cheques or banker's drafts, just British pound notes -- up front, in the hand.

I conducted lengthy negotiations from the wall-mounted telephone in the corridor of Wessex Studios. Eventually the fee was agreed. That left just one more problem -- equipment. All the Clash's gear had been set up in the studio for the recording session. There wasn't time to dismantle it and send it to Finland. And anyway it had taken three days to get the right sound, and we just couldn't afford the cost in studio time to go through the whole process again.

From phone calls to Scandinavia, I achieved a personal coup through Thomas Johansen, Abba's road manager, who agreed that we could use Abba's PA and sound equipment. Abba were the only group which had ever made me star-struck. I anticipated the tingle of excitement when I would plug my jack-plug into Agnetha's amp ... As it turned out, I received more than a tingle.

We flew to Finland with the minimum crew. Rob Collins, a sound engineer whom we had used before, was called in at short notice, and Jeremy Green, the tape operator at Wessex Studios, was recruited on the spot to look after the guitars and amps. With the lift-off of the plane we all felt the lifting of pressure on the band. A kids-out-of-school atmosphere took over, which lasted for the whole trip. We were away from the pressures of recording and our money problems, with the prospect of earning cash-in-hand. We were on holiday!

The festival site just added to the holiday feeling. The changing rooms were some caravans behind the stage, next to a beautiful lake, with fir trees and sunshine. It was a long way from the streets of Notting Hill and the garages of Camden Town -- the subject matter of most Clash songs. And the band were playing outdoors, in the daytime -- almost unknown for them. The Clash had second billing at the festival, after Graham Parker and the Rumour. They hadn't played support for any band since the Sex Pistols on the Anarchy in the UK tour of December 1976. We knew Graham Parker and his gang, and they couldn't understand it: `How come you're playing support? How much are you getting paid?'

We played dumb and giggled up our sleeves.

Shortly before the Clash were due to play, the band asked: `Where's the money?'

`It's OK. It's safe back at the hotel' said the organizers, surprised at the demand.

`No, we want it now, in our hands, before we go on'

I was dispatched to the hotel with one of the Finnish promoters to fetch the money. He found it hard to believe that I was standing in the hotel room counting out 7500 [pounds sterling] in sterling, all wrapped in 100 [pounds sterling] bundles. This wasn't the normal way of doing business. The festival was funded by the Finnish government, under a youth arts development programme, so it was unlikely that they would have paid us short. But we had learnt from long experience not to trust anyone. Satisfied that it was all there, I bundled the notes into my atomic pink flight case and rushed back to the stadium.

`We've got the cash, lads. On you go!'

The band prepared to run on-stage when I noticed a buzz from the PA. I rushed on to connect a loose jack-plug, grabbed a mike-stand with my other hand and performed a backward flip across the stage as an electric current took a short cut across my chest. The crowd went mad with excitement. They thought my acrobatics were part of the act. I went mad. Grabbing the microphone, I yelled abuse about incompetent Finnish technicians and generally called for the whole of Scandinavia to plummet into an obscene hell, led by the cheering folk in the audience. They loved this even more, and as I went backstage to resume my grip on the case full of cash, the Clash went on-stage to a huge roar. The band put on a good show, fuelled by the Finnish vodka they'd demanded backstage before the set.

After the set the holiday mood continued. We watched Graham Parker's band from the stage wings, shouting encouragement and taking the piss. I had a cheap camera, and went on-stage and asked Parker to smite for a photo mid-song. He would sing a line and then say, `Fuck off, fuck off', to me out of the corner of his mouth.

After the concert all the bands and their entourages went to a huge banquet in the dance hall of the hotel. Everyone was working hard at getting wrecked -- Finnish beer is state-licensed, and labelled with one, two or three stars according to strength. We went for three-star. As was my way, I got more wrecked than most, and fell into a stupor, still with a dead-man's vice-like grip on the case of cash.

Eventually Joe and Paul decided to carry me to the bedroom. They told me the next day that they couldn't lift me and had had to drag me across the floor to the lift. My back had the carpet burns to prove it. As Joe passed Graham Parker, pulling me and the pink cash bag, Parker had shouted to him: `Who is that cunt?'

`He's our road manager,' said Joe. `He's looking after us.'

Waiting at Turku airport for our return flight, we were still in high spirits. We felt like we had got away with a bank heist. As photographer Pennie Smith said later: `Being on the road with the Clash is like a commando raid performed by The Bash Street Kids.' During the flight I sat with the briefcase on my lap and handed out wads of cash, making a real game of it.

`One for you, one for you, one for me ...'

Everyone stuffed wedges of notes into their pockets, to the shocked astonishment of the other passengers and flight staff. We had cash at last and wanted to flaunt it. We had bypassed our creditors and the banks, and had been fellow conspirators throughout the gig. Little did Graham Parker and the Rumour know that although we had played support, we had been paid more than them.

We changed planes at Stockholm, and each of us bought a copy of Playboy for Tony Sanchez's expose of Keith Richards and the Rolling Stones. Mick Jones was a `Keef' lookalike, and he knew it, but his attempts to live a Keef-like lifestyle were better hidden from the public gaze. He leant across and swiped me across the back of the head with his rolled-up Playboy . `Don't you ever do the same thing to us, Johnny,' he said.

And now I have. When I told Mick about this project he had no objections.

`Don't worry, I won't go on about the cocaine and the birds,' I said.

`That's a pity,' said Mick. `I could do with the credibility.'

`Fuck authority,' said Joe. `I loved that, "Who's in charge?" "He is ..." and there was you completely out of it,' and he leapt on to the burning log straddling the bonfire, sparks and flames leaping up around his fire-dance, his frame, still sporting a fine quiff, silhouetted in the aureole surrounding the eclipsing full moon. He looked just slightly older, slightly wiser, than the figure he cut on-stage twenty years previously.

And I clicked and slipped backwards. The Clash were filming a video for London Calling ...

The Baker and I had turned up at Battersea Park at midday. A bright spark at the council had thought of installing sleeping policemen in the park road, presumably to slow down runaway wheelchairs. It was murder manoeuvring the Clash's atomic pink flight cases of amps and speakers over them to the floating jetty, grandly called Battersea Pier, which bobbed up and down with the tide. Don Letts, who was doing the filming, turned up on a motor launch, dreadlocks flying, with the film crew. We set up the backline as if we were playing at the Lyceum -- amps, leads, mikes, stands, PA to roll back the sound. And we waited and waited for the band to arrive. We buttoned our coats against the growing cold of the afternoon and even Letts' good humour began to wane. Cold hours passed and the sun set. It began to rain and the Clash turned up. All the band's equipment was standing in the drizzle getting soaked. Don had sent out for some lights and I sent out for some Remy Martin. I wanted to pack up and go home. The boat pulled out, riding the swell of the river, and Letts was shouting instructions to the band through a megaphone, like he was at the Boat Race.

`All right, hold it. When we do that section again all gather around the mike then spread ...'

It was so weird it cheered me up, and the band ran through it again and again, patiently and professionally, looking urban and urbane, and wet. It was as if they had known it was going to rain, and known it was going to be filmed at dusk. Joe wielded his faithful old guitar, with its `Ignore Alien Orders' sticker. Paul sported a wide-brimmed gangster hat; Mick was in a dark suit, with a red tie and handkerchief sending off flashes of colour. Every time Topper hit the drums spray bounced up into his face, sparkling in the artificial light. Between takes I mopped at their rain-soaked guitars and faces with towels in a little wooden hut nearby, as they slugged Remy and hugged each other against the cold.

Finally, it was done and the band pissed off in a cab. Baker and I, cold, wet and starving, were left to pack everything away, without even the roar of the crowd to see us home.

Baker whinged. `Look at this stuff -- it's soaked. How are we going to dry it off? It's ruined."

I grabbed a mike-stand and dumped it into the water. Anger welled into strength, and I picked up a wedge monitor, hired from Maurice Plaquet, and with a roar hurled it into the Thames. To our surprise it floated, and, rocking with laughter, we watched it bobbing under the fairy lights of Chelsea Bridge.

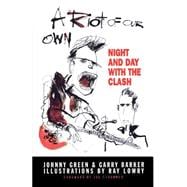

Copyright © 1999 Johnny Green and Garry Barker. All rights reserved.