Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Pearl Harbor, a cultural crossroads | p. 3 |

| Coming to America | p. 8 |

| The morning after | p. 18 |

| We need you after all | p. 34 |

| Linguists on the horns of a paradox | p. 47 |

| Expanding their numbers | p. 55 |

| Going overseas | p. 67 |

| Veterans becoming heroes | p. 77 |

| From Cassino to the gates of Rome | p. 84 |

| The 442nd on the offensive | p. 99 |

| Closing in on the Arno | p. 113 |

| On the other side of the world | p. 124 |

| They also served | p. 137 |

| Frank Merrill's samurai | p. 143 |

| In the darkness of the Vosges | p. 150 |

| The story of the lost battalion | p. 163 |

| La Houssiere and beyond | p. 174 |

| The spring offensive | p. 186 |

| The irony of Dachau | p. 200 |

| To Genoa and victory | p. 209 |

| Final actions in the Pacific | p. 221 |

| Frank Fujita and the other lost battalion | p. 225 |

| The last man in | p. 233 |

| The military intelligence service in Japan | p. 242 |

| After the war | p. 247 |

| Japanese American recipients of the Medal of Honor during World War II | |

| List of internment camps | |

| Text of the presidential unit citations awarded to the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team | |

| Table of Contents provided by Blackwell. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

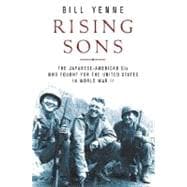

Excerpted from Rising Sons: The Japanese American GIs Who Fought for the United States in World War II by Bill Yenne

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.