The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

My name is Garnet Olivia Hubbard. In five weeks and three days, I'll be thirteen.

My sister Opal, who is fifteen and the self-appointed Boss of the Entire Universe, rolls her eyes every time I remind her I am about to become an honest-to-Pete teenager. She says I'm still a baby. If I'd called her a baby when she was thirteen, I'd still be recovering from my injuries. Anyway, it isn't true. I'm no baby. I've had to grow up fast, because of what happened on Mama's birthday last summer.

It was the first day of August, the last day of my regular life, and I didn't have a clue. Just before daylight I got up, unlatched the back door, and went to the garden. The tomato plants and Mama's pole beans were heavy with dew. Already the thermometer on the back porch was pushing ninety degrees, but I didn't mind the heat. I love summer, when there are no math quizzes or vocabulary lists. You can sleep as long as you want, then wake up to a clean slate where anything is possible, and you can make the day into whatever you want it to be. I wanted Mama's birthday to be perfect.

Deep in the corn rows the air was humid and still. I thumped the bugs off the corn, gathered four ears, and picked half a dozen tomatoes for the dinner Opal and I were making for Mama, a tradition as important as going to the opening game at the ballpark every spring, or staying up until midnight on Christmas Eve. The birds were waking up and singing their little hearts out. The morning freight train clattered through town bound for Dallas, its whistle echoing through the trees along Piney Road. At Mrs. Streeter's house next door, the screen door slapped open and her three-legged cat shot out and perched on the porch railing. Mrs. Streeter, in her nightgown and rhinestone-studded glasses, marched across the grass to fetch her copy of the MirabeauDaily Monitor. She picked it up and waved to me on her way back inside.

Then the lamp in my room came on, a sign Opal was up, getting ready to bake Mama's cake. As for Mama herself, she was still out like a light, getting her beauty sleep so she'd be fresh for her party.

My daddy was on his way home for the celebration. He worked on a ship called theWorld Explorer. It was based in New Orleans but sailed all over the Gulf of Mexico looking for places to drill for oil and gas. Mama said it was dangerous work, but Daddy said the pay was good, and he liked being outside instead of behind a desk. The worst part of his job was his being gone so much. Already he'd missed my first baseball game of the season and Opal's portrayal of Juliet in the eighth-grade play, which had gotten written up on the entertainment page of the paper. Me and Opal had been mad at him for missing our important events, even though it wasn't his fault. When it came to Mama, he wasn't taking any chances on making her mad by missing her big day. He got permission to come home for her birthday, even though he'd have to turn right around the next morning and drive all the way back to New Orleans.

I cut some okra off the stalks and headed for the house. The screen door banged as I came in, and Opal said, "Shhh! Don't wake her up."

I shucked the corn, rinsed the tomatoes, and helped Opal make a double batch of chocolate frosting. When the cake was done, we set it on the rack to cool, then tiptoed past Mama's door to get cleaned up. Later, we made PB & J sandwiches and iced tea for lunch and ate on the back porch, then finished frosting the cake.

We heard Mama's door open and close, and then the squeak of the faucet in her shower. Opal cocked her ear, listening for the beginning of Mama's daily serenade. Occasionally Mama sang a gospel tune, but mostly she sang country. She claimed to know the words to every song ever played on her favorite station, WSM. Today, though, we didn't hear anything but the shower running and the banging of the old pipes.

By five o'clock we could hear Mama opening and closing drawers, moving around in her room, getting ready for her grand entrance. Opal gave up watching for Daddy and went to our room to play records. I was sitting in Daddy's easy chair by the window, readingBlack Beautyfor the umpteenth time, when I saw his pickup barreling down the road, kicking up a cloud of dust. I yelled for Mama and Opal and ran out the door to meet him.

"Hey, sugar pie!" Daddy unfolded himself from behind the wheel, scooped me up, and twirled me around. "Where's your mama?"

"In her room, getting ready for the party. She's been in there all day. Opal thinks Mama's in one of her bad moods."

"On her birthday?" He set me on my feet again.

"Uh-huh. She didn't sing in the shower today. And last night she hollered at me and Opal for no reason, and then she started crying."

Daddy shook his head and took his duffel bag out of the truck. Then he reached under the seat for a bouquet of roses wrapped in wet newspaper. "Maybe these'll cheer her up."

But we both knew better. When Mama was in one of her snits, it took more than flowers to bring her around.

"Is that Mama's present?" I pointed to a box in the back of the truck.

He nodded. "But let's leave it here for now so we don't spoil the surprise." He handed me his duffel bag to carry. "Have you been practicing your fastball like I showed you?"

"Yes, sir, Daddy. Want to see?"

"As soon as we're through with supper."

We went up the steps and into the house.

"Melanie?" Daddy called out. "I'm home."

And then Mama twirled into the kitchen, smiling like the refrigerator saleslady on TV. "Hey, Duane."

"Happy birthday!" Daddy handed Mama the roses and bowed like a prince in a William Shakespeare play. "I was afraid they'd wilt before I got here. August in Texas. Hotter than the hinges of hell."

"Don't cuss," Mama said. "It's not refined."

Daddy laughed and swept her into his arms and kissed her with loud smacking sounds until she started giggling.

"Duane Hubbard, behave yourself!" she said. But she was smiling, a hopeful sign that relaxed the knot in my stomach that all week had been winding tighter and tighter.

For days Mama had been jumpy as a long-tailed cat in a roomful of rockers. She'd tried to hide it, but Opal and I noticed how she looked right past us when we talked to her, like she was seeing something else entirely. Plus, she was in constant motion. When she crossed her legs, her foot jiggled, and her fingernails drummed on the tabletop. Late at night she prowled the kitchen, cleaning cupboards and banging pans just like she'd done the year I turned ten, when she'd left us and headed for Nashville.

For as long as I could remember, Mama had the idea that she could be the next big thing in Music City if only she could get there. Performing at the Ryman Auditorium was her one dream in life. The time she left us, she got as far as Dallas before Daddy caught up with her and sweet-talked her into coming home. Since then, me and Opal have had to stay alert for signs she might leave again. Trying to keep your mama from running off is exhausting. I was glad Daddy was home, even if only for one day.

Mama put her roses in a vase and finished setting the table. Then Opal came running down the hall and Daddy picked her up and twirled her around.

"Daddy!" she yelped. "Put me down. I just finished curling my hair and you're getting it all messed up."

"Oh, don't be a fussbudget. You'd look pretty if you were bald-headed."

Opal waved him away, but any fool could see how Daddy's compliment pleased her. She said, "The chicken is ready for the pan."

"Okay," Daddy said, "but first..."

Me and Opal started laughing because we knew what was coming next. A shaving cream company had put up silly advertising rhymes along the highways, and Daddy brought us a new one every time he came home.

He said, "Here's one I saw this morning. 'Spring has sprung, the grass has riz, where last year's careless driver is.'"

Then me and Opal yelled, "Burma-Shave!"

"I don't see what's so funny," Mama said. "It's downright tragic, if you ask me. And besides, there is no such word as 'riz.'"

"Oh, Mama, don't be a spoilsport," Opal said. "It's just for fun. Besides, it reminds people to drive carefully."

If there was anybody in the great state of Texas who needed good driving reminders, it was Mama. Behind the wheel she was a regular menace, driving too fast, singing too loud, stomping on the brakes half a second before the traffic lights turned from yellow to red.

Daddy tied one of Mama's aprons over his jeans and started heating oil in the iron skillet we used for frying chicken. When the oil was smoking hot, Opal dipped the chicken pieces in egg batter and flour, and dropped them into the pan. Daddy dug a fork out of the drawer and started turning the chicken as it browned, all the while telling us about the men on theWorld Explorer, and that last Thursday they had helped rescue a man who had abandoned his rig after his welding torch sparked a fire.

"You see?" Mama was sitting at the table, watching us make dinner. "I told you it's dangerous out there. You'll get yourself killed one of these days, Duane Hubbard. Then what?"

Daddy kissed her on the nose. "You worry too much. Hand me that platter."

Me and Opal set out our feast, and an hour later the four of us were sitting at the kitchen table, full as ticks. The fan turned in a slow half-circle, blowing the hot, stale air. On the TV in the living room, the news announcer talked about the Olympics coming up in Rome, Italy, the integration sit-ins happening all over the place, and whether Senator Kennedy could be elected president and save our country from the Communists.

A couple of years before, the Russians had sent some satellites called Sputniks into space and the Communists had held a big convention in New York City. Ever since, people were scared the Communists would take over America. At school we practiced ducking under our desks and throwing our arms over our heads, in case the Russians bombed us to kingdom come. Like that would save us.

One day over lemonade and sugar cookies, Mrs. Streeter told Mama the whole world had turned topsy-turvy, and that she was more afraid of the Negroes, who had had enough of drinking from special water fountains and staying in hotels just for colored folks, than she was of the Commies. Several Negro kids had integrated a white high school up in Arkansas, and Mrs. Streeter said it was just a matter of time before colored people took over the whole country. Mama said it was a crazy time all right, and truly amazing that the outside world was totally discombobulated, but things in Mirabeau had hardly changed at all.

As we finished Mama's birthday dinner that night, I had no idea that my own personal world was about to turn upside down too.

Daddy polished off the last drumstick and took a long drink of iced tea. Opal left the table and came back with Mama's cake. I lit the candles, two pink and white 3s we'd bought at Woolworth's. We gave Mama her presents, a quilted pot holder and an African violet from me, a lipstick from Opal. FIRE AND ICE, it said on the bottom of the tube.

"Thank you, girls!" Mama beamed first at me, then at Opal. "I don't know what I'd do without my precious gems."

The sound of her voice washed over me like a rush of warm water. Happiness worked its way up from my toes and curled around my heart. Daddy leaned over the table and kissed Mama on the lips. It was such a perfect moment I felt like bawling. I wished for a camera to capture that night, to freeze it in time, but that would have been a mistake. As I found out later on, the worst pain in the world comes from remembering a happy time when you're stuck knee-deep in misery.

"Make a wish, Mama," Opal said. "Before the fan blows your candles out."

"Oh, my land, I cannot think of a single thing to wish for."

Opal rolled her eyes at me. We both knew better. Mama knew exactly what she wanted, the one thing she'd coveted since she'd first laid eyes on it back on the fourth of July.

We were standing outside Sadler's Music Store that day, our dresses limp as yesterday's handkerchiefs, our chocolate ice-cream cones melting and running down our elbows in a brown, sticky mess. Waves of heat danced on the sidewalk and seeped through the concrete so hot it burned my feet through the soles of my sandals. I stood on one foot and then the other while Mama cupped her hands to her eyes and peered into the window.

"There it is, girls," she said, her face lit up like she'd swallowed a lightbulb. "That guitar is just like Cordell Jackson's. If your daddy asks, tell him this guitar is what I want for my birthday."

Behind Mama's back, Opal heaved an exasperated sigh. All Mama talked about was how Cordell was the most talented woman in the music business. Not only did she write and record her own songs, she produced them too. Mama was determined to be the next Cordell Jackson.

Now, watching Mama cut big slabs of her devil's food birthday cake, I could barely sit still for thinking about how happy she'd be when Daddy gave her the guitar. Mama set the cake on our plates, Opal poured everybody some more tea, and we dug in. But Daddy couldn't wait to give Mama her present. He sat on the edge of his chair, his eyes snapping with his secret. After a couple of bites, he set his fork down and headed out to the truck. "Wait here," he called to Mama. "I'll be right back."

Mama licked frosting off her fork and leaned back in her chair, craning her neck. Daddy hollered, "Don't peek!"

She laughed and winked at Opal and me, so excited she could hardly stand it. She put down her fork and covered her eyes. Then Daddy came back toting a huge box topped with a red bow.

"Ta-da!" He bent down and kissed the top of Mama's head. "Happy birthday!"

Mama looked first at the box, then at him. "Duane Hubbard, what in the world?"

Daddy ripped open the box and lifted out a vacuum cleaner. "Top of the line, sugar, and looky here. A toe switch, so you don't even have to bend over to turn it on."

Mama stared at him like he was from Planet Krypton, then busted out bawling.

"Aw, Melanie, don't cry," Daddy said. "If I'd known how happy this would make you, I'd have got you one long before now."

Mama jumped up, ran into their room, and slammed the door.

Daddy looked like a grenade had gone off in his hand. "What did I do?"

Opal started clearing the dishes. "We told you what she wanted, Daddy. We told you twice."

"A fancy guitar, when all she knows is three chords? That don't make a lick of sense."

"Mama says the best songs ain't nothing but three chords and the truth." I ran my finger through a gob of chocolate frosting on the side of the cake, licked it off, then handed Opal the cake plate.

"Don't say 'ain't,'" Opal said. "People will think you're ignorant." She turned back to Daddy. "Women don't want practical things for their birthdays. You're supposed to give them something romantic, or something fun."

"I brought roses," Daddy said, a hurt expression in his eyes. "I think that's pretty romantic."

"Mama had her heart set on that guitar."

"Giving her that guitar would be the same as saying it's okay to run off to Nashville chasing some foolish notion that doesn't have a prayer of coming true." Daddy rubbed his chin. "I love your mama a whole lot, but let's face it. She can't sing worth a flip. Getting turned down by those music people would break her heart."

I thought about the summer when I was nine and readBlack Beautyfor the first time, and how I dreamed of having a horse of my own. Mama said we couldn't afford one, and anyway we had no place to keep a horse. She said that holding on to a dream was almost as good as having it come true, but it didn't seem like holding on to her dream was enough for Mama.

Daddy went out to the front porch, and me and Opal washed the dishes. When we finished, we poured some more tea and took our glasses out to the back steps. It was still hot enough to fry eggs on the sidewalk. Lightning bugs flashed in Mama's Queen Elizabeth rosebushes. The last of the sunlight glittered in the trees.

I dug my toes into the silky dust, fighting the choked feeling in my throat. It was hard to take, how fast Mama's special day had gone wrong. But lately it seemed like everything was more complicated. Last year everything was easier. Opal and I spent whole days hunting arrowheads on the riverbank, making Christmas ornaments out of tinfoil, or wandering around downtown. We'd start at one end of Central Avenue, passing by the dentist's office and Mirabeau Hardware, then we'd thumb through the new magazines at the drugstore and stop in at the Purple Cow for chocolate ice cream with sprinkles. Sometimes we'd wear swimsuits under our clothes and take the long way home, down the highway and across the wooden bridge to the river where the younger kids played water tag, and the teenagers who had cars played backseat Bingo after the sun went down.

But Opal had turned fourteen in February and didn't have time for me anymore. Now all she wanted to do was talk on the phone, listen to her forty-fives, and write secrets in her diary, which she kept under lock and key. As if I didn't know what she was writing about.

I took a gulp of iced tea. Far off, lightning flashed.

"Looks like rain." Opal stretched out her legs, fished an ice cube out of her glass, and crunched it with her teeth. In the soft light, with the summer sun still glowing on her skin, my sister was the spitting image of Mama -- blond and blue-eyed, so fragile-looking people fell all over themselves taking care of her. Mama said I took after Daddy's people -- brown-haired, plain, and sturdy enough to take care of myself. But I didn't feel sturdy at all. Not with Mama holed up in her room crying, and Daddy sitting alone on the front porch with nothing but his hurt feelings for company.

In the morning he'd be gone again, and I was afraid for him to go away mad, afraid he might decide not to come back. I watched the clouds roll in, trying to think of some way to fix everything that had gone wrong, but I couldn't think of anything. As much as Daddy loved baseball, I didn't think watching me practice my fastball would be enough to cheer him up. And it was no use talking to Mama. When she got mad, she stayed mad for quite a while.

"Can you believe he gave her a vacuum cleaner?" Opal sighed and crunched another piece of ice. "I swear, Garnet, men are thick as fence posts. That's why I'm never getting married."

"You will if Waymon Harris asks you."

Opal shot me a look. "What do you know about it?"

"You're hoping he'll be at the howdy dance next week. Plus, you're dying to sit beside him in homeroom next year."

The mention of school made us both grin. We loved getting ready for a new year. I liked the starchy feel of new clothes, and the way my shoes hugged tight to my feet after a whole summer of going barefoot. I loved the smells of chalk and lemon floor polish, and the yeasty smell of rolls baking in the cafeteria. Most of all, I liked sitting in the dark auditorium watching films about archaeologists searching for the lost tribes of Africa, or scientists discovering the atom. Subjects that made you think you could do anything you wanted in life, even if you came from a small town like Mirabeau, Texas.

Opal lifted her hair off her neck and let it fall. "Waymon might not even be in my homeroom," she said, taking up her favorite subject again. "There's a good chance he will be, though." She pretended not to care one way or the other, but the way she mooned over Waymon's name told a different story. "Harris comes right before Hubbard, and I don't think they'd break up theHs. Would they?"

Before I could answer, Opal grabbed my shirt. "Wait a minute. How did you know about the howdy dance? If you've been reading my diary, Garnet Hubbard, say your prayers and prepare to die."

"If you kill me, you'll never find out."

She grabbed an ice cube from her glass and stuffed it down my shirt. I rubbed one of mine into her hair, then took off running. She caught me from behind and we rolled on the grass like TV wrestlers, until we were both weak with laughter. My sister pinned me to the ground. "Well?"

"Opal and Waymon, sitting in a tree," I panted. "K-i-s-s-i-n-g."

"Youhavebeen reading my stuff, you little snoop!" She let go of my arms and jumped up. "Let's go in," she said, slapping at her legs. "I'll kill you later. The mosquitoes are eating me alive."

She hauled me to my feet and peered into my face, her eyes clear as rain. "Listen. Don't tell Mama I like Waymon, okay? You know she goes crazy every time I mention boys. Just because she eloped with Daddy she acts like I'm going to run off with the first boy who asks me."

"I won't tell. And I didn't read your diary. All I have to do is listen when you're on the phone with Linda." I slapped a mosquito off my arm. "Besides, Mama's so mad she probably won't talk to us for a week."

"As if the whole vacuum cleaner mess is our fault." Opal held the screen door open for me and we went in. "Poor Daddy."

We left our glasses on the counter in the kitchen and went down the hall, past our parents' room. A sliver of light, and Mama's voice, raw with tears, spilled out.

"Nobody in this family cares what I want!" Mama was shouting. The sound of breaking glass brought me and Opal to a dead stop outside their door. I wondered what Mama had smashed to smithereens this time. Last time it was a red and yellow vase Daddy had brought her from Mexico. Later, when she got over her mad spell, Mama glued the vase back together, but it was never the same. You could see cracks running all through it.

Daddy answered Mama, his voice too low to hear. More glass broke. Then Daddy's voice rose. "You want to run off chasing some dream that's only going to break your heart. What about me? What about the girls?"

"Yes, what about the girls? I have spent every day of the past fourteen years taking care of them and I am sick of it. It's your turn!"

A roaring started deep inside my chest and rose to my ears, so I couldn't hear what Daddy said back to her. They'd fought plenty of times, but this felt different. It felt like the end of everything. I wanted to run, but it was like I was glued to the floor, listening to the sounds of my family coming apart.

Then we heard Daddy's footsteps coming toward the hallway. Opal dragged me down the hall to our room and slammed the door. I was crying by then, my heart stumbling on the thought that Mama didn't want us anymore. But Opal's expression was hard and flat.

"What if she really does it this time?" I asked. "What if she picks up and goes to Nashville and never comes back?"

"Who cares? If she wants to go, let her go." Opal dragged a brush through her hair. Her eyes met mine in the mirror, and when she saw how scared I was, her voice got softer. "Don't worry about it. Nashville's just a dream, to get her through the hard times." She jumped onto her bed and strummed her hairbrush like it was a guitar. "It's o-nly make be-lie-ee-ve."

That was Mama's favorite Conway Twitty song, the one she played over and over again. I thought of how she made us stop talking every time it came over the radio. I could be in the middle of asking an important question about my homework, or trying to figure out which dress to wear for picture day; it didn't matter. Mama just had to hear every word of that song. It was amazing, how she could be standing in the kitchen, shelling peas or slicing tomatoes, and yet seem to be somewhere else altogether. Even more amazing: I had got all the way to twelve years old before realizing Mama wished I'd never been born.

We heard the TV come on in the living room, but neither of us wanted to face Daddy right then; we didn't know what to say. The rain had started, so we stayed in our room and listened to Opal's records for a while. I tried to get a head start on my summer reading, but the problems facing Huck Finn seemed tame compared to mine, and I gave up. After the ten o'clock news, Daddy turned the TV off. Opal stripped off her shorts and T-shirt and pulled on her baby doll pj's. She tossed my faded orange Texas Longhorns nightshirt onto my bed and switched on the fan. "Okay if I read for a while?"

"I don't care."

She went into the bathroom and brushed her teeth, then flopped onto her bed and opened her copy ofA Thousand Hints for Teens. She'd bought it by mistake, thinking it was a fan magazine, but now it was her Bible. Sometimes she read aloud from chapters like "Beauties Aren't Born, But Made" and "How to Talk to Boys." But that night she just flipped the pages back and forth, then snapped off the light.

I lay in the dark for a while, listening to the rain dancing on the roof and the quiet hum of the fan, hoping Opal was right and that everything would be normal when I woke up. The next thing I knew, it was morning and Mama was bending over me, calling my name.

I played possum. I didn't want to open my eyes and see her face for fear I'd start bawling again. But she switched off the fan and the August heat pressed down on me. Then it was either wake up or suffocate. I opened one eye. Across the room Opal was still asleep, her mouth open, one arm thrown across her forehead.

I sat up. Our room looked the same: The watercolor picture I'd painted in sixth grade and the blue ribbon I'd won for it at the county fair were still hanging on the wall next to my horse posters. Opal's portable phonograph sat in the corner, her collection of forty-fives stacked up like pancakes. Her lipstick collection and an unopened bottle of My Sin perfume she was saving to wear for You-Know-Who spilled across the dresser. But now everything felt as foreign as Timbuktu, because Mama looked at us and saw everything that was wrong with her life.

"Wake up," Mama said again, despite the fact that I was already sitting straight up, watching her. She wore a white dress with tiny red dots all over it, a red belt pulled tight at her waist, and her good summer shoes -- white high-heeled pumps with gold butterflies on the toes. On her wrist was the charm bracelet Daddy had given her a long time ago, before the yelling started. She reminded me of an expensive present, all wrapped up and tied with a bow.

She shook Opal's shoulder. "Come on, baby. Rise and shine."

"Go away," my sister mumbled, but then the heat got to her, too. She sat up, shoved her hair from her eyes, looked Mama over, and said, "Who died?"

"That's not nice." Mama's voice sounded raw. "If there's anything I hate, it's a kid with a smart mouth."

"If there's anythingIhate, it's a mother who tells lies!" I yelled. The words formed themselves, escaped my mouth before I could stop them. I expected Mama to get mad, to ask me what I meant. But she didn't say a word. Instead she pulled her truck keys from her pocket.Copyright © 2006 by D. Anne Love

Chapter Two

I shot Opal an I-told-you-so look. Mama was going to Nashville and never coming back.

Opal turned her ice-hard eyes on Mama. "Where's Daddy?"

But Mama wasn't ready to talk. Instead she started emptying our closet, dumping our jeans and dresses, sandals and tennies onto Opal's bed. When the closet was empty, she started in on the dresser drawers, taking out my underwear and socks, our swimsuits, and Opal's day-of-the-week panties. Finally she said, "Daddy left early to miss the traffic. He said to tell you bye, and he'll call soon."

I pictured my daddy on his ship in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico, a long way from anywhere, and tears pushed at the back of my throat. Then Mama said, "Garnet, get the suitcase."

I pulled the green suitcase from under my bed, the one we got the year Daddy drove us clear to Dallas for the Texas State Fair. Mama piled our stuff in it, everything all jumbled together, not folded neatly like she's always after us to do, and then I realized she was taking us with her. Even though I was worried sick about Daddy, my insides felt a little bit lighter. Mama couldn't have meant what she'd said the night before. Not if we were going with her.

"Are we going to Nashville, Mama?"

"Eventually. You girls will stay in Willow Flats with your aunt Julia till I'm settled in Music City. Then I'll come back for you."

"What about Daddy?" Opal crossed her arms and glared at Mama.

"That's grown-up business, Opal. I don't believe I care to discuss it. Now hurry up. I want to get on the road before it gets any hotter."

"Aren't we ever coming back here?" I asked. Suddenly Mirabeau, Texas, seemed like the best place in the world.

"Oh, for the love of Pete!" Mama spat. "You're carrying on like Mirabeau is the garden spot of the Western world. But you just wait. Once you see Nashville, you'll never want to come back here."

Opal flopped onto her bed. "I'm not going."

"Of course you are!" Mama said. "Julia will be happy to have you."

"We don't even know her!" Opal yelled. "All my friends are here. And I don't want to miss the dance. You said I could go, Mama. It's for all the incoming freshmen. I've already picked out my dress and everything."

"There'll be plenty of dances later." Mama tapped the toe of her shoe on the hardwood floor.Click. Click. Click. "Don't make me drag you out of that bed, Opal."

"If Opal isn't going, then neither am I!" I folded my arms the way Daddy did when he had had enough foolishness. "You said I could go shopping for school clothes with Jean Ann. You promised!"

"Sometimes promises have to wait," Mama said. "And I am not in the mood for any more back talk." She sat on the suitcase lid and snapped it shut. "Both of you, get cleaned up and get going. I want you in the truck in twenty minutes or I'll make you wish you were. Understand me?"

I saw how eager she was to drop us off like a pair of stray kittens onto some musty old relative, and something inside me died. I pushed past her, ran down the hall to the bathroom, and slid the lock into place. I turned the water on and sat in the shower, crying until my skin wrinkled and I felt hollowed out inside. There was only one explanation for how fast everything had changed: Mama had gone crazy. I was desperate for Daddy to come back and straighten her out. But he was burning up the road between Mirabeau and New Orleans, headed for theWorld Explorer. I rubbed my hair dry, wrapped myself in the towel, and went back to our room. Opal was standing at the dresser in her pj's, raking her makeup into a paper bag. I put on the denim shorts and white T-shirt Mama had left out for me and waited while Opal got ready.

We went outside. Morning sun poured through the trees. Down the street a lawn mower started up. Mama was already sitting in the pickup, a map and her bucket purse on the seat beside her. The windows were down, and Elvis was singing on the radio. Our green suitcase and Mama's two white ones were in the back, along with some taped-up cardboard boxes and a spare tire. I climbed in next to Mama. Opal crowded in beside me and slammed the door.

"Okay!" Mama said in a voice that seemed desperate for a new start. "Nashville, here I come!"

"Aren't you going to lock up the house?" Opal didn't bother to hide her contempt, but Mama didn't even notice.

"I left the key with Mrs. Streeter," Mama said. "She'll look after things till moving day." Mama ground the gears and handed me the map. "Here, Garnet. You can navigate."

The maze of red and blue lines spreading like a cobweb over the page made my stomach hurt. Map reading was not one of my talents.

"Your aunt Julia's house is right about there." Mama stabbed with her finger at a tiny black dot somewhere in the vicinity of Oklahoma and gunned the engine. My back pressed into the seat as the truck roared out of the yard and onto the blacktop. I stared at the map. Willow Flats seemed like a foreign country, a nothing place a hundred miles from nowhere. I stole a glance at Opal, but her face was blank; she'd gone off by herself to someplace I couldn't follow.

We took the road that ran past my school. The building looked August-lonely, the windows shut tight, except for the ones in the principal's office. Mr. Gatewood's Ford was parked in the shade of the oaks out front. The teachers' parking lot was empty. The swings where the little kids play stirred in the breeze. Sunlight bounced off the school's tin roof and poured into the cab, so bright my eyes watered.

We passed the field where Daddy taught me to pitch a fastball and hit fly balls, and I realized I'd left behind my collection of baseball cards and my pitcher's glove. But there was no use asking Mama to go back for them. She was driving like the devil was chasing her. The truck rumbled across the wooden bridge straddling the river, where a couple of boys were fishing with bamboo poles. When they saw Mama barreling down on them, they plastered themselves against the railing and waved as we flew past. When we reached the road to Jean Ann's house, I couldn't stay quiet any longer.

"Wait, Mama!" I yelled above the rattle of the engine. "Can't we at least stop and say good-bye?"

"Oh, sugar, there's no time. But don't you worry. As soon as I get established, we'll throw a real party for Jean Ann and all your friends. Yours, too, Opal."

"Big whoopee," Opal said. "By then they'll be living out at Sunny Acres drooling into their oatmeal."

Opal's drama club had performed at the retirement home last spring, and the sight of all those sick old people had depressed her for weeks.

"Well, it's certainly nice to know you have so much confidence in my abilities, Opal Jane."

Five minutes later we were parked in front of Sadler's Music. Mama grabbed her purse. "I'll be right back."

Opal slid down in the seat and shook her head. "She has no idea how much I hate her."

"Daddy says we aren't supposed to say we hate anybody."

"Fine. I won't say it. But that doesn't mean it isn't true."

I chewed the insides of my cheeks until I tasted blood. I wanted to hate Mama too, so it wouldn't hurt so much to let her go. But down deep I still had a soft spot in my heart for her, because of how bad she wanted her dream to come true.

A few minutes passed and then Mama came out of the store with a guitar case in one hand, her purse and a paper sack in the other. She handed the sack through the open window. "Those are my picks and extra strings. Don't lose them."

She set the guitar case in the back and braced it with the suitcases, then got behind the wheel. "Is everybody ready?"

When we just glared at her, she looked away. "Okay," she said under her breath. "Okay. Here we go."

She put on her white-framed sunglasses, turned up the volume on the radio, and started her concert. She knew every song by heart -- the words, the artist, the year it came out, its highest number on the Billboard chart.

"'Heartbreak Hotel,'" she shouted as we reached the highway, and the last of Mirabeau, and the last of my old life, slid away. "Elvis's first gold record. Nineteen fifty-six." Another song blared.At the hop, hop, hop. "Danny and the Juniors!" Mama informed us. Like we cared. "Now that was a great dancin' song."

It was after one o'clock when it finally dawned on Mama that her children hadn't eaten a bite all day. In a dusty town off the main highway, we stopped at a grocery store for a loaf of bread, some bologna, and Moon Pies. Mama gave Opal a handful of change and we went to the back of the store, dropped the money in, and slid three cold Coca-Colas out of the cooler.

There was no place to sit down to eat in the store, so we got back in the truck. Opal made sandwiches and passed them around. Mama hiked her skirt and drove with the cola bottle between her knees. "If I have to downshift, darlin', you grab this Co-Cola fast," she said to me.

For a while we were busy eating, and the only sound was the truck engine and the songs on the radio. Then the traffic slowed and we saw a detour sign. "Shoot!" Mama said. "Hold my Co-Cola, Garnet."

I grabbed the bottle and she popped the clutch and drove down a steep hill to a rutted track below. She sped past all the cars stopped on the roadway, until we came to a gravel road. There she made a hard turn that sent me crashing into Opal's shoulder.

"Ow!" Opal shoved me with her hip. "Get off me."

"I can't help it if she's driving like a maniac!"

"Hush up!" Mama said. "Look at the map, Garnet, and tell me where we are."

I unfolded the map and tried to get my bearings but it was impossible, with Mama whipping along the rough road, the truck sliding on the loose gravel, the radio blasting, and Mama asking me every ten seconds where we were. Plus, trying not to spill her Co-Cola.

Opal grabbed the map just as we flew past a road marker. She squinted at it for a minute and yelled to Mama, "We're on some farm road, about forty miles south of Mount Springs. You can get back on the highway there."

Mama nodded. "Where's my Coke?"

I handed her back the bottle and she drank it down, her eyes on the road. The radio station faded to static, and Mama worried the dial until she found another one. She kept singing and announcing the play list: Buddy Holly, Bobby Darin, Patsy Cline.

We rounded a curve and Mama hit the brakes. In front of us was a truck with a sprayer on the back, spewing fresh tar on the gravel. The stench rolled through the truck. My eyes watered. Moon Pie and bologna burned sour and hot at the back of my throat.

Mama leaned on the horn. The driver stuck his arm out the window and turned his palm up, like he was asking her what she expected him to do. The road was narrow and too curvy to pass, and we'd come too far to turn back. Mama backed off, and we inched along behind the tar truck, following it up one hill and down the other.

My stomach tingled. Cold sweat rolled down my back. "Stop, Mama!" I said. "I'm going to be sick."

"Oh, you are not. Mind over matter, Garnet. Think of something else."

But then I threw up all over my sandals, the sleeve of Opal's blouse, the map, and Mama's bucket purse. Mama pulled off the road and stopped. Opal jumped out, yelling something, but I was too sick to care. My stomach heaved and heaved. Heat shimmered on the road. Black spots danced in front of my eyes. Mama ran around the front of the truck and caught me before I fell. She said something to Opal, but her words sounded far away.

"Get your head down," Mama said. "That's right, down between your knees. Now breathe." It seemed like Mama kissed the top of my head then, but maybe I imagined it. When the world came back into focus, I saw that Opal had changed her shirt. She handed me a clean one too, and gave me the rest of her Co-Cola. Mama cleaned the map with a wadded-up tissue. "Looks like there's a town between here and Mount Springs," she said. "We'll stop there for tonight."

She rubbed my back the way she used to when I was little. Back then when I was sick, I'd lie in her bed that smelled like sunshine and lemons, eating strawberry Jell-O and chicken noodle soup, playing with books of paper dolls she'd bought at the five-and-ten. She gave me pink stuff when my stomach hurt, and cherry cough medicine when I caught a cold. Pretending to be a good mother. Pretending she cared. But now she ran her fingers through her hair, sighed deeply, and said, "How about it, Garnet? Can we go now?"

When I tried to talk, a loud burp came out instead.

"Oh, that's attractive," Opal said.

"Leave her alone." Mama wadded up our soiled shirts and tossed them into the back of the truck. She wiped off the dashboard and sprayed the cab with perfume to kill the smell. Then she noticed the gobs of black tar sticking to her good summer shoes. She shot me a hard look, toed them off, and threw them in the back too. She yanked open the door. "Well, what are you waiting for? An engraved invitation? Let's get a move on."

We got back in the cab, which still stank of bologna and puke. Mama gunned the engine and we took off again. I must have slept, because the next thing I knew, it was getting dark and Mama was pulling into the Sunset Motel. There were nine cabins, an office with peeling paint on the door, and a flashing neon sign that said VACANCY. Opal and I waited in the truck while Mama went to the office. When she came back, we hauled our stuff into number six, a room that smelled of sweat and cigarettes. There were two sagging beds with dirt-brown spreads, a table and chair, and a speckled mirror. In the bathroom the faucet dripped rusty water into a cracked sink.

"Charming place, Mama," Opal said. "Who's the innkeeper, Norman Bates?"

Opal had seen that new movie about a psycho boy who ran a motel. I wasn't allowed to go, but I heard all about it from Opal. She said Tony Perkins was so cute, it was hard to believe he could be that creepy. But he scared her so bad that for a while she was afraid to take a shower unless I stood guard outside the door.

"I am much too tired for your sarcasm, Opal," Mama said. "If you don't like the accommodations, you're free to leave." She opened her suitcase. "You can pout all you want, but I am getting cleaned up, and then I am going to that drive-in we passed for a burger and a shake. You can come along or stay here. I don't care."

When the bathroom door closed behind her, Opal threw herself onto the bed. "Wow. She is really off her rocker. Wait till Daddy finds out."

"That's what I'm counting on," I said. "As soon as we get to Aunt Julia's, we'll call him. Maybe he'll come and get us in time for your dance."

"I just hope we're not stuck with this Julia person for the rest of our lives," Opal said.

"You reckon she's as crazy as Mama?"

Opal snorted. "Nobody's as crazy as Mama."

And then, right on cue, Mama's voice came sliding out of the shower. "Crazy they call me, sure I'm crazy..."

Opal snickered, and that set us both off. We laughed until our sides ached, until Mama twirled out of the bathroom in a cloud of Shalimar and blue satin, her face shiny clean, her hair done up in a halo of blond curls. "If you're going with me, girls, shake a leg. I'm starving."

She unpacked her makeup case and put on fresh powder and lipstick. Opal and I took turns in the bathroom, and an hour later we pulled into the drive-in. Mama found a space near the end of the row and gave our order to the carhop. Music poured from a dozen car radios all tuned to the same station. A couple of teenagers started dancing. Halfway through the song, others joined in. Under the flashing neon lights Opal's face was the very picture of sadness. I knew she was thinking about missing the howdy dance, and I got mad at Mama all over again.

The song ended and another one began.

"Be-Bop-a-Lula!" Mama opened the truck door and grabbed my hand. "Come on, Garnet. I'll teach you to dance." In her high-heeled sandals and tight blue dress, with the light shining on her golden hair, she looked so beautiful I could barely breathe. Looking at her was like looking at a painting you could never afford to buy. Part of me wanted to fall into her arms and hold on for dear life, but another part didn't want any more memories that would make it harder to let her go.

"I don't want to."

"Fine." She let go of my hand like it was a hot coal, but she kept swaying to the music. "Opal? Want to dance with your mama?"

Opal stared. "Do I want to dance with you, after you've ruined my entire life? No, Mama, I don't believe I do."

"Oh." For a moment her face fell, then our mother smiled like she was doing a commercial for toothpaste. "Suit yourself, but it's sure a waste of a good song. Gene Vincent. Nineteen fifty-six. Boy howdy, that was a great year for music."

The carhop brought our order and we ate without talking. On the way back to the motel Mama was quiet, and I could tell she was thinking hard on something. Sure enough, as soon as we were inside number six, she sat us down and said, "Listen, girls. I know you're mad at me and you think I'm not being fair. But in this life, if you want something real bad, you've got to pay the price."

Opal crossed her arms, Daddy-style. Mama went on. "You two have your whole lives ahead of you, but look at me. Past thirty, even if most people think I don't look a day over twenty-five. If I'm ever going to make a musical career, I've got to go now, before it's too late."

She took a clipping out of her bag and passed it to us. WIN A RECORDING CONTRACT it said in red letters. PRODUCERS LOOKING FOR NEW TALENT. IT COULD BE YOU!

"I almost threw this out with the trash," Mama said. "It was lying under a tuna fish can, but I saw it just in time. I'm telling you, girls, when fate sends you a present, you don't dare send it back unopened." She folded the clipping. "I'm going to get one of those contracts. You'll see. One day you'll thank me for getting you out of Mirabeau, Texas."

"What's wrong with Mirabeau?" Opal said. "It's a nice place. I like it there."Mama laughed. "That's just because you've never been anywhere else. You're just like your daddy. No imagination. Believe it or not, there's a whole wide world beyond the Lone Star State, and I intend to see it all."

She thought for a minute, tapping her shiny red nails on the tabletop. "I've been thinking about a new name."

"How about Judy S. Carriot?" Opal threw herself onto the bed.

"Very funny, Opal. Be as mean as you want, but I need a stage name. Nearly everybody in Nashville has one. You know what Conway's real name is? Harold Jenkins!"

"If I was stuck with a name like Harold Jenkins, I'd change it too," Opal said.

Mama ignored her. "I can't very well go to Nashville as Melanie Hubbard."

"Why not?" I asked. "It's your name. But I guess you're throwing it away too, along with me and Opal."

"I'm not throwing you away. I am sending you to visit family! It's not that I don't want you."

"That's not what you told Daddy," Opal said.

Mama's face turned red. "I'm sorry you heard that. But that's what you get for sticking your nose where it's got no business being. Besides, I didn't mean it the way it sounded."

"How did you mean it?" Opal's voice cracked, and my own throat felt tight.

Mama's eyes filled up, and for a minute I felt sorry for her, but then I thought about having to leave my whole life behind, and how she was running away from Daddy, and my insides went hard.

"There's no sense in talking more about it," Mama said. "It's plain to see you're both determined to be mad at me."

Opal dug her pajamas out of our suitcase. "I'm going to bed."

"Me too," I said. "My stomach feels funny again."

I got ready for bed and climbed under the covers. Opal slid in and turned her face to the wall. After Mama switched off the lamp, I lay wide-eyed in the dark, bone tired and achy, but too keyed up to sleep. I kept wishing I was back home in my own bed. And I couldn't stop thinking about Daddy, wondering if he'd called home yet. I turned over and punched the musty-smelling pillow, trying to sort out all the feelings churning inside me, flipping like a coin from one side to the other.

Mama was brave for going after her dream; she was the world's biggest coward for leaving Daddy and sending us away. One thing I knew for sure: A longing for the extraordinary had grabbed ahold of her and was burning her up inside, so hot and fierce that her heart had gone stone cold toward everything and everybody standing in her way. That was Mama.

Fire and ice.

Copyright © 2006 by D. Anne Love

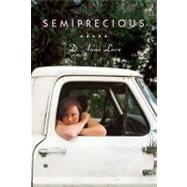

Excerpted from Semiprecious by D. Anne Love

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.