Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Why I saved the tape I can't begin to say, so I decide it must have saved itself for me.

As I scoured the house for a blank audiocassette, I found it -- unmarked, tossed in an old shopping bag from some long-ago Christmas. It's part of the limitless stuff you take when you move from one house to another, stuff that may end up lost or discarded or simply relegated to a cardboard box in a dusty corner, under tons of other stuff.

The tape player is on a low shelf under the TV. I pop in the tape and push play, and the gooseflesh rises up on my arms. It's Nino. He's talking on what must be an old answering machine tape from years ago -- way back in 1993, maybe '94. Amazing that this is still around.

My breath stops in my throat. I sink to my knees, then sit cross-legged on the floor by the tape player. I put my head down and listen hard, feeling the vibrations of the words as they come out of the speaker. When I turn up the volume, it's like he's speaking right into my ear.

Nino.

As far as I can tell, it's a business call. That's how I date it -- 1993. It must have been recorded then, because shortly afterward Nino switched from bulk paper sales to a career in funeral planning.

He speaks down low -- or maybe it's the tape quality -- so I can't hear a lot of the words. There's something in there about C-fold towels and rolls of waxed paper and paper bags by the gross and how he can get a better discount for quantity.

Back then he worked for Advance Paper and Chemical of Wilmington, and he sold all these janitorial products to big industrial firms as well as to small companies and mom-and-pops. He was good at it, made a good living for the time, and it was all due to his gregarious nature. Nino had an innate friendliness that just drew people to him and him to them. He was a natural salesman who leaned hard on his Italianness and that kind of blunt, humor-filled haggling to get people's respect and trust. It worked.

Of course, like most Italians, he especially loved selling to places where he could grab a bite to eat: restaurants, pizza places, sub shops. Those were his favorite stops, and he'd gladly find an excuse to linger for a while during the workday at some little roadside deli and order the biggest, sloppiest sub going, with lots of provolone and prosciutto and peppers and oil. Sometimes he'd take one wrapped for the road and share it with me when he got home. The man loved to eat: meat and potatoes, fried baloney sandwiches, and heaps and heaps of pasta.

It was an old joke between us. Nino had the vanity of a man who had always been attractive. In middle age, he watched with dismay as his waistline slowly expanded, but he could never curb that big appetite. And me, no matter what or how much I ate, I could never get up past 118 pounds.

Whatever he's talking about on the scratchy old tape -- the this-and-that of business or a detail about a pending deal -- the thrill for me is simply hearing his voice, a voice I haven't heard in more than a thousand days.

•••

There was a time I would have been unnerved by this sudden encounter with my late husband. I might have felt angry or desolate. I might have fallen back into the dark, closed-in place I went to when he first died. Today, I'm amazed to realize that this feels only good: a moment of reunion, warm, like an unexpected clasp of hands. I catch a glimpse of myself in the glass door of the stereo cabinet, and I'm smiling.

I can't talk back to him, can't ask him the questions I've yearned to ask or tell him the things I think he'd like to know about our lives since he left us. I think he knows anyway. Somehow, putting one foot determinedly in front of the other, we've all of us -- me and the kids -- come through it. We've all learned how to be glad again, unself-consciously glad, and our thoughts of him are mostly good.

Hi, Nino, I tell him in my mind. I've been thinking about you so much. You are so welcome here.

On the tape, too, is a message from my mom.

"Hi, Debbie," she says. Her voice, always matter-of-fact, sounds softer, like it's wrapped in gauze. "I just wanted to wish you a happy Nurses Day...."

I want to catch every sound, every pause and intake of breath. Unbelievable. How long has it been?

"Happy Nurses Day."

That was so like Mom, to notice a made-up holiday on the calendar and call just to acknowledge it. She was unerringly thoughtful. Not effusive and never sentimental, just thoughtful and nice.

Natalie Matilda Purse (divorced from my dad, she took back her maiden name after Darlene, the youngest of us, turned twenty-one, and she always called herself "Gnat," like the little bug) was not one to spend hours on the phone. Once she said what needed to be said, it was, "Well, I've got to hang up now." And off she'd go back to her treasured solitude, with her cats and her teapot and her crossword puzzles.

But she never lost touch with her kids, with Robert or Gary, with Darlene or with me. In a day or two she'd find a reason to call again, and we'd exchange the few words that were necessary to stay close and caught up.

We've missed both of you, I think, hoping my thoughts carry across from the place I am to the place -- if it is a place -- they now occupy. Nino, Mom, we never imagined we could miss you as long and as hard as we have. Nor did we know that one day it would all be okay again. We never thought it could.

Well, Mom, it's okay. Really okay for the first time in a long while.

Nino, the twins are doing so much better. You'd be proud to see them as they evolve out of that college kid thing into accomplished, responsible adults: Melissa with a good job at a bank, happy and engaged (yes, to Jeremy -- it's lasted), Michael working hard and studying and feeling a whole lot better.

They're healing up, too, from all that happened. I know it would be incredibly important to you to know that. We're through the worst of it, out of the keenest part of the sorrow and into the life that comes after.

Nino and I were married almost twenty-five years and were in fact just days from our silver anniversary when he died. We'd planned no big party; that was out of the question with both the kids in college. And we'd reluctantly decided that the second honeymoon we planned years and years ago -- a twenty-fifth anniversary trip to Hawaii -- would have to wait till the next big milestone ("Maybe the thirtieth," said Nino).

I managed to be okay with the change in plans, and Nino did come up with a great consolation prize: a pair of antique diamond earrings. The fact that he bought them secondhand from a coworker dimmed their luster a little bit, but really, they were gorgeous.

But overall, and secretly, I was disappointed. I'm the kind of person who would have said, Ah, to hell with it, let's rent a hall and hire a great Italian caterer and invite all our friends from Maryland and Jersey and Delaware. Let's get a DJ and bring all Nino's musician pals to play, too. Let's drink and dance, eat Chesapeake Bay crabs and baked ziti and roast beef sandwiches, and we'll worry about the cost later. You only live once.

I still mourn him, Nino, my husband, Michael and Melissa's father. But now mourning has a kinder face, an almost companionable nature. The fact that I can love the sound of my late husband's voice, feeling comforted by it rather than saddened, means I've turned a corner in the long, lingering good-bye that is grieving.

Once it was almost impossible for me to believe that the acute, relentless yearning that was my grief for Nino would ever let up. Somehow it has, though. Time has blunted the most painful edges. I've started to experience my memories as friendly little prompts that remind me of all the things I loved about my husband, without making me ache in that bad old way.

I went through this first with Mom. She died way too soon, at sixty-five. It had taken us the better part of a lifetime to grow as close as we both wanted to be, to get past the mother-daughter turmoils and become dear friends. And just as I was starting to love that and count on it, she was gone. Heart failure. I was bereft. Our best conversation had just begun.

The hurt came in waves, as sharply physical as the pain of childbirth, with the same sort of ebb and flow. For a while, I'd be okay. She was gone, I was coping, like everybody eventually does. Then it would well up again, a sadness so big I'd want to physically outrun it.

It took months, maybe a year before it started to ease up. I came to think of the experience as sorrowing. Not a noun. A verb. Sorrowing. It was an active thing, a thing I had to do and work at. On rough days I'd feel like the sailor on choppy waters who has to just grip the sides and hold on. I'd literally tell myself, Debbie, come on. This thing has a curve. It goes up, it hurts, it hurts, then you cry, then you crash down, and then it's calm for a while. Ride it out, girl.

In time, as the waves started to recede, I started to remember Mom as she deserved to be remembered: not with pain but with gratitude. For her grace and loyalty, her intelligence and independence, her pungent honesty, and her quiet devotion to us.

This isn't anything you learn to do better the second time. With Nino's death in April 1998, grief came around again; again, it was unexpected. But this grief was all new; this was hurricanes and torrents that propelled Melissa and Michael and me to places I never imagined we'd have to go.

My husband, my friend, companion, lover, and partner of twenty-five years, was murdered, shot down by the man who came to our house looking for me.

Well, he was not looking specifically for me, Debbie, at least not until he saw me in my yard that spring day. He was looking for a woman, any woman or girl he deemed attractive. He was looking for someone to savage and rape and, if necessary, to kill.

You'd think such a crime would take great planning, great cunning and secretiveness. No. He just drove around until he found someone -- me. He started with the neighborhoods near his home in Bear, Delaware, then wandered into Newark, about five miles away, then into Academy Hill, where we lived, then onto Arizona State Drive. Simple as one plus one. It wasn't a dark and stormy night; it was the middle of the afternoon, a bright, blue Monday in April.

That afternoon, I was in the side yard of our new home. I was busy planting a bank of rosebushes there, along the perimeter of our property.

It was my big landscaping project. If I got it right -- doubtful to begin with -- maybe our corner lot would start to rival some of the prettily landscaped and manicured yards throughout the rest of Academy Hill. I envisioned it as a fringe of gorgeous bursting color that Nino and I could see from our kitchen window. Not that I'd had much luck at this sort of thing. When we first moved in, just ten months before, an overgrown herb garden near the side door had defied my most valiant attempts to tame it. Finally, feeling utterly inept, I called on some friends from our old neighborhood just over the state line in Elkton, Maryland.

"They're taking over, like the Blob," I said. "Help!"

They did. Over one long autumn weekend, it took all six of us -- Kathy and Barb, Dale and Sam, Dot and me -- to wade through the intractable tangle of mint and basil and tarragon and thyme. We tied some off to stakes. We deadheaded some and pulled others out completely. We came out scratched up and dirty, but everyone went home with bundles of herbs to dry, and from then on I managed to keep the creeping foliage at bay.

Yard work was definitely not my forte. But I was game. I was willing to have another go at it. That Monday I threw on pink sweats and a gray hooded sweater and pulled on some work gloves. Then I headed outside into the nicest day of the year so far to plant my roses, pink and coral, bloodred and ivory.

From the start we called it our dream house: the big Cape Cod on a corner lot in Newark, Delaware. With a cathedral ceiling in the foyer, five bedrooms, and (best of all) a deck with a hot tub, this was it: our reward for a lifetime of hopes, dreams, and economic conservatism. When we moved here from Elkton in July 1997, Nino and I knew we were staying put. We planned to stay here for the rest of our lives.

From the time we lived in our first tiny one-bedroom apartment, we had worked toward this. Even as newlyweds, we talked endlessly about what we wanted in what I thought of as our "someday" home: a refuge and a haven, in a quiet neighborhood where we'd be comfortable leaving the house open and the car door unlocked. We refined that vision for more than twenty years, and in 1997, when we started looking in earnest, we knew just what we were after.

"I want lots of light, plenty of windows," I said. "No faux paneling, no small rooms, nothing dark. Everything light and airy."

"We need more space, certainly," said Nino. "Enough room for the kids to come home weekends and bring their friends. Oh, yeah," he added, as if it was an afterthought, "a place to park the boat."

Besides everything on our wish list, there were very practical reasons we needed to move back to Delaware. We both worked there, and it made sense to live closer to our jobs. But the big thing was Michael's choice of college, the University of Delaware. Out of state, we just about managed his tuition. In state, we got a financial break that made life a whole lot easier.

We found everything we needed -- the location, the space, and a small-town, Mayberry feeling -- in a development called Academy Hill.

Academy Hill is only about twelve miles from Wilmington, but it might as well be in another galaxy. One of many subdivisions in the area, it was designed to feel as removed as possible from the teeming cities and four-lanes and eight-lanes that crowd the area and link it to Philadelphia and New York, Baltimore and Washington.

The subdivisions have subdivision names: Arbour Park, Eagle Trace, Beaulieu. We looked at them all, but Academy Hill struck us as ideal, with spick-and-span homes of various models, and little of the cookie-cutter sameness of older communities. Here, behind carefully cultivated shrubbery, surrounded by insulation walls to blunt the roar of Interstate 95, Nino and I had found our version of the good life.

Of course, Academy Hill wasn't really Mayberry. It was a suburban approximation set along those four-lane and eight-lane crossroads. But for us, at this stage of our lives, it was the right choice. We'd worked hard for this: the breathing space, the peace and quiet, the elbow room. We may have stretched our finances a bit to bankroll the new life, but it was worth it. With lots of space inside and out, we kept spare rooms for Michael and Melissa, both away at college. I decorated to my heart's content, with my ever-propagating collection of Beanie Babies, my cats and cows, my angels, andGone With the Windplates.

I had always liked the country look, and I indulged myself, especially in the kitchen, which was as bright and airy as any in a magazine. This home on Arizona State Drive was the model home for the community when it was under construction, so it had great window treatments (daffodil yellow in the breakfast nook) that we got to keep.

We made new friends easily. Though something of a homebody, Nino was still very social within the neighborhood. He made it a point to meet the people on our street, to the extent of going up and greeting perfect strangers. We were especially close to Gene and Karen Nygaard next door; we became comfortable enough to walk in and out of each other's homes, barely knocking, for a cup of coffee or whatnot.

Gene's an engineer, but he may have missed his real mission in life: he's great in the garden. His property always looked like a showplace -- like something out of Martha Stewart, with jewel-like lawns and lush flowering trees. Sometimes I'd compare his place with ours and cringe. We practically had tumbleweeds blowing across the yard, and I'd think, Gee, he must hate living next door to us.

But Gene was sweet. When he saw our landscaping left something to be desired, he gave us an unofficial and belated housewarming gift: four rosebushes to plant out front.

"They don't get enough sun over here," he said, digging them out from a spot at the top of his driveway and placing them, one by one, in black plastic garbage bags. "But you've got light all day."

Later he wished he could take back that friendly gesture. It was a hard burden for him. But how could we assure him that nothing that happened that Monday was his fault?

He never said the words straight out. But I know Gene continued to torment himself. What if he hadn't given me the roses?

"What if?"

Whenever they arise -- the what-ifs -- I dodge them fast, before my mind has a chance to take them seriously.

Any circumstance, good or bad, can be endlessly deconstructed, reconstructed, rescripted. I could certainly do it with April 20, 1998.

What if, that day, I had gone shopping instead? I had a shopping list. I needed milk, juice, cereal.

What if Nino had decided to join me out in the garden after work instead of going inside for a snack? He was a maniacal mower: he trimmed that grass down so low that it never reached the quarter-inch mark. The yard was something we could have worked on together.

Or what if we had never moved to Academy Hill? There were literally dozens of beautiful communities in the same area, so why here, and why this house?

Or what if it had rained? What if?

I could go that road, easily, trying to mentally change and rearrange everything in forty-plus years of living that might have altered the events of one day. But do I want to do that? Would I really make changes in the whole of my life just to try to avoid a few minutes of it, the minutes it took for so much of my future to be determined?

If so, why not go back even further and ask, What if I had never met and married Nino? What if I had never found this great job in Delaware? What if I didn't like roses? But I did all these things. I couldn't help it, didn'twantto help it. And I certainly couldn't decide now to regret it.

When what-ifs come up, I do the mental equivalent of sticking my fingers in my ears and humming, loud. I refuse them, just block them out.

Some things you must accept, even things from which you naturally recoil, like the gross and evil things and people of life.

Some things, damn it, you must just accept.

And what if I'd had a busy night the night before? I was a hospice nurse on overnight call. Sometimes during my shift I'd be on the run for sixteen hours nonstop, visiting patients at home, counseling their families, and monitoring their care before rushing off to the next stop, which could be two blocks down the street or an hour up north.

But it didn't happen that way. I had a quiet Sunday night with no calls. Otherwise, I would never have taken on what was for me a strenuous chore: working in the garden on Monday. I would have been too bushed.

And if I had not been in the garden, the cruiser -- the man in the green Plymouth -- would never have spotted me. He would have driven past the empty yard on the corner of Arizona State Drive, and some other woman or girl would have been the recipient of what turned out to be my fate. I would have remained unchosen.

Later on, I probably would have heard about a crime, a murder, a rape, and been horrified and alarmed and sorry for some other woman and her family. I would have wondered, Oh, my Lord, what if that had been me? and talked about it with people at the market or the post office. I would have shuddered at the thought that it could happen so close to my home. I would have sent up a little thank-you that nothing that shattering had ever happened to our family.

And my life -- busy, happy, relatively uneventful, sometimes mundane -- would have rolled out over the years, much as it had in the years before.

Of course, I don't go there, to "what if."

Except sometimes when I do.

Usually, after my shift ended at 8 A.M., I said good-bye to Nino then slept most of the morning away. Most days I managed to wake about one in the afternoon, just in time to make lunch and loll in front of the TV for one delicious lazy hour, usually to watchAll My Children.Then, time to gear up for another night.

Nino always said that by late afternoon on these days, once I was thinking about and preparing for work, I became a different person. "Debbie," he'd observe, "I can always tell when you're going into work mode."

I could tell, too. It was a very conscious thing, but, by this point in my career, pretty automatic, too. It was important for me to center myself and marshal my energies for the night to come. I seldom knew how the night would play out, but I couldn't see patients with my energy flagging or half my heart in it. I had to be all there, every time. No one dies twice. I have a lot of professional pride about this. I couldn't allow myself to get it wrong, not even for one of my patients.

Dying is hard work. The job of a hospice nurse is to make the arduous physical transition a little easier, helping ease the pain so patients can deal with what dying's really about: taking leave of a world of people and things they love. It's our job to educate the dying person and his family about what's going on at every stage of the leave-taking: from month to month, and at the end, from moment to moment. So that they, not we, are in charge of how a death goes.

Being admitted into hospice, which is designed for those with a six-month life expectancy or less, is a great commitment for family members. For the patient plan to work, they must learn all they can about things like symptom management, the care of a bed-bound patient, how drugs work, and how to combat the nausea and vomiting that accompany some drugs. This is how it goes, and the workload can be hard and unpleasant.

But thanks to hospice care, families get to do this important event -- death -- together, actively. They're not helpless spectators in an antiseptic cubicle, at the whim of rotating strangers in white coats. Patients get to die at home, in their own beds, with kids and grandkids in attendance, surrounded by their own things: framed photos and cherished keepsakes and pets -- it's funny how often they want their pets there.

Given the choice, people can transform dying into a luminous affair, even a celebration. I once attended the death of a woman whose family gathered at her bedside to sing her favorite hymns. "Amazing Grace." "Will the Circle Be Unbroken." With lamps lit and candles all around, they filled the room with an almost incandescent energy. Her death was as peaceful as any I have ever seen. None of this could happen in a hospital cubicle.

As a nurse, it wasn't my place to partake in the emotion of a death. The whole philosophy of hospice precludes it. My role was that of helper, a support -- strictly supplemental. But like every hospice worker I've ever known, the time comes when you break the rules. The bonds develop, whether you want them to or not. Your heart and your humanity don't always observe the protocol.

Take Keith. At the outset, I would never have imagined that I could fall in love with this young man or his family. They were more distant than most, to the point of being aloof with me and the other nurses. Understandably, Dot and Charles were fiercely protective of their son's privacy and reluctant to let anyone observe their collective sorrow.

Keith had AIDS, at a time when AIDS was not just a death sentence but a moral and social scourge. He was just thirty-four. After the death of his partner, Keith moved back home to be with his mother and dad, and together they waited for the inevitable. Months passed before I could gain their confidence; they were reluctant to reveal themselves, even to Alex, one of our spiritual counselors. It was as if they thought that we, too, might tar their son with the stigma that often accompanied a diagnosis of AIDS -- that we would make it our place to judge his lifestyle, his choices, and his fate.

But in time they eased up. They stepped out from behind their emotional armor. They began to look forward to our weekly visits, when Keith, with evident pride, always wore his AIDS ribbon. They knew we cared -- how could we not? Keith couldn't help but respond to kindness, because in it he recognized himself. He was one of the gentlest, most caring people I have ever known. Once the barrier between us fell, it became impossible for me to stay with the company policy of professional detachment. Keith just melted my heart.

During the couple of hours a week I typically spent with him, Charles always set up a TV tray, and Dot always served homemade iced tea and cookies. In nice weather, we sat in the garden, where we chatted about anything at all: news, politics, entertainment, especially the movies. I had to admire Keith, who insisted on leading as normal a life as possible. In the direst circumstances, he went to the movies at least once a week with his father. For him, this was no small task. As the disease progressed, so did the wasting of his body. But his spirit was almighty. Even near the end, when what was left of him could have blown away on a breeze, Keith's vitality overwhelmed me. We'd hug, and I could feel the skeleton beneath his skin, the way his bones interlocked, even the protrusion of his joints. But boy, when Keith hugged me, I knew I was being hugged.

Keith fought hard to live. He was in the program a little more than two years. As he began his last decline, I stepped up my visits to twice a week, then three times. When the time came to prepare for his death, his parents requested that I be there, no matter who was on call. This, too, required some juggling. An important tenet of hospice nursing (besides not getting emotionally involved to begin with) is to let go, let the team take over when the shift is through. Share the burden. Break that rule and you'll burn out fast.

But for me, this was no longer the death of a patient. This had become a death in the family. When Dot and Charles called that May evening, I jumped in the car and hurried over. The three of us sat at Keith's bedside, hearing his faint final breaths and gently giving him permission to go. His favorite music played in the background. Then Keith, the patient I now called a friend, died with dignity in the room where he grew up.

With rare exceptions, I'm on call Sunday through Wednesday. The rest of the week is mine to do whatever I want. I'm on call three nights out of seven then I have four days off. Kind of a lopsided way to live, but I like the freedom, so the schedule suits me.

That Sunday night, my pager was silent. No one was dying or even required care, so I didn't have to go out. I even managed to sit down with Nino and Michael (visiting for the weekend from his dorm at the University of Delaware -- with his laundry, of course) to watch a movie. We rentedKiss the Girls,with Morgan Freeman.

It didn't exactly make for restful sleep, this thriller about a serial murderer who targets women. It left me with a scary feeling. On the job I often visit the shabbier neighborhoods of Wilmington and Newark and Bear, which all have their problems with crime. And often as not, I'm out there in the overnight hours.

Nino usually came with me when the neighborhood was dicey, but this wasn't always possible or practical -- he had to work, too -- and like any woman, I occasionally wondered what I'd do if I were approached or harassed or, God forbid, mugged. From time to time I'd thought of taking martial arts training to help me feel more secure. I never got around to it.

I lay down about eleven and tossed a little, wishing I hadn't watched that damned movie. This wasn't like me. Usually I loved a good scare. Finally I dozed off and didn't get up till Nino did, a little after five in the morning.

Copyright © 2003 by Debra Puglisi Sharp

Chapter One

Mondays always seem more hectic than other weekdays. It shouldn't be true for Nino and me. His work schedule isn't your typical nine-to-five, nor is mine. But Mondays are Mondays are Mondays.

Though as routine as ever, this Monday is busy from the start. I've had a decent night's sleep -- an extraordinary seven hours -- so I'm up. But for some reason, I'm a little out of sorts. Nino's grumpy, but that's how he greets every day till he gets his quota of caffeine. I'm relieved when he heads out for his morning cup of coffee from the Wawa, a chain convenience store in our area. I used to make coffee at home, but home-brewed doesn't suit him -- only Wawa's will do, and he stops there every morning for a big sixteen-ouncer, cream, and sugar, along with his daily pack of Winston Lights.

I feed our four cats, then feed Fish, a single massive grommie who reigns in solitude in his big tank. Fish belonged to my mom. I inherited him when she died, and since then we've developed a strange intraspecies relationship.

Nino and the kids don't believe me, but I'm convinced there's affection for me behind those big fish eyes; in fact, when I walk through the dining room, his eyes follow me everywhere with what seems like lively interest. This morning I pause by his tank, and as usual he lifts his big pink head for a pinch of food.

I have to smile.

"Hey, Fishie," I say this day. "Morning, buddy."

The first minute I get, I pour a strong cup of tea and call Michael, bent on continuing a discussion that began over last night's dinner. Of course we end up bickering.

On Tuesday there's a school dinner, where our son is supposed to receive an academic award. But he's being typically balky. Modesty is a commendable trait, but Michael is almost too retiring; he never wants to flaunt his accomplishments before the world, even the little world of his classmates and teachers.

Michael has strong principles about this sort of thing. To him, there's no contest but the contest with himself. He shuns the idea of being judged "better" than someone else. It's a very pure way of thinking, noble even. I respect it. But Nino and I are proud parents, and we wish just once he would change his mind.

We talked about it at the table on Sunday, where he put forth his usual arguments: he didn't compete against other people, academically or in sports. All that mattered to him was doing his personal best, and he didn't know why this stuff was so important to us.

"Well, soon you'll be out there interviewing for jobs, Michael. It'll look so impressive if you've won all these awards...."

"Mom," he said, with exaggerated patience, staring down at his meat loaf and peas, "if they want to know about me, they can just look at my GPA."

At that, Nino sighed -- a big, deep sigh that meant he was starting to get ticked off. "Michael, please," he said, biting off the words. "It's one night of your life. Do it for your mother."

Good move, Nino -- if at first you don't succeed, there's still the old guilt trip. I'd tried it myself, earlier in the day: "Michael, honey, come on. Just do it for your dad." Michael will not be persuaded.

Up till now, all his awards have ended up at the bottom of his bedroom closet, buried under a pile of track shoes. It's become a tug-of-war between us -- I'll display the running trophies or plaques on the hearth, and when I'm not looking he'll turn them face down or lock them away altogether.

This morning around eleven I give it another shot -- "Come on, honey" -- and I hear him groan on the other end of the line.

"Mom, what's the big deal with this?"

"The big deal is it means a lot to your dad." I hear the edge creep into my voice; I'm getting impatient, too. "If it doesn't mean anything to you, do it to please him. How much effort does it take?"

From there it's all downhill. One or the other of us, I can't remember which, hangs up.

Stubborn kid. I stand with the receiver in my hand, fuming. Then I decide to shrug it off. No use fretting this into something bigger than it should be.

Stubborn kid. Stubborn parents.

I'll talk to him again later, when we've both cooled off.

Nino stops home for lunch, and I do the fried baloney thing.

Fried baloney is a kind of family joke, and the kids still snicker when their dad demands what is for him a childhood tradition: four thick slices hot off the grill, piled high on two pieces of bread with mustard. It's comfort food for Nino, just as tomato soup with grilled cheese (we called them "cheese-and-cook-it" sandwiches) put me right back in the kitchen of my girlhood home in Burlington, New Jersey.

After lunch he girds himself to make a phone call that could have an appreciable impact on our money situation. It's to Melissa's financial aid office, and he's calling to inquire about one of her loans.

By choice, Nino has always handled money management for our family, including those damned college loan applications. But he hates every contentious second of it. He constantly reminds me how frustrating it is to fill out the endless forms, year after year, trying to convince the ruling boards that we're not too well-off to qualify for aid and going into battle with the dense, multiple levels of bureaucracies that hold the keys to the kingdom.

Worst of all, he says, is doing this by phone, where he has to listen to prerecorded messages directing him to make one of a dozen menu choices then listen to Muzak for minutes at a time while praying for a live (and hopefully responsive) human being.

He's doing that now: waiting, his ear pressed to the receiver, growing more flushed with each passing minute. He shakes his head. "You know, Debbie, I don't know what you'd do if you had to handle this on your own."

It's not the first time he's expressed this sentiment. All our married life he's chafed about being the one who has to balance the checkbook and get everything paid on time. His refrain: "Debbie, I'm glad you don't have to deal with this. You'd never be able to figure it all out." According to Nino, I remain the tender, hapless little woman who can't cope with the important things of life, things like mortgages and tax returns and car repairs. Those are man's work.

Today, though, wrangling with the loan people, he's reached the end of his tether. When he crashes the phone down, I know it hasn't been a successful call.

He grabs his jacket and storms toward the door. "You know what?" he says. "I might as well just take my car and drive off the Delaware Memorial Bridge."

And he's gone.

Two down. Both Nino and Michael are mad.

Well, okay. Everybody's at cross-purposes today, but I don't have to let it wreck my own day. It's still early, and it's beautiful out: sunny and breezy, not too cold, perfectly April. I'm free until 4 P.M., when I call in for my assignment. I've got just enough time to accomplish something, so at about two in the afternoon, I lug the four rosebushes out to the side yard, where I've already dug four deep holes and filled them with the good organic soil recommended by Gene.

With trowel and spade in hand, I start to dig. I feel clumsy and inexpert. Homey, one of our four cats -- the only outside one -- curls beside me in a square of sunlight.

About 3 P.M., Nino comes home from work. He parks his Jeep in the driveway and ambles over. By now he seems okay. The lines have eased out of his forehead, and his shoulders are down, relaxed. Thank God.

I'm surprised he doesn't offer to join me; Nino loves yard work. The joke in our family is, "When Dad gets out the weed whacker, stand back." He couldn't be bothered with edging and raking, but if it involves a tool that makes noise, he's all for it. Gene Nygaard's always telling him he trims the grass too short: "Hey, you really need to bring the blade up on your mower." Nino just laughs and, heedless, roars on.

But today, he's not interested. Must be tired. "Better you than me," he says, then smiles at Homey. "Hey, looks like you've got a helper there."

"Yeah."

He heads inside, where he typically grabs a snack after work.

"Do me a favor, Nino," I call after him, "tell me when it's 3:45. I need to report in to work."

I labor on, packing loose earth around the balled roots of the rosebushes. After a while it seems like it must be getting close to four. But Nino hasn't called. As a nurse, I need to be on time; he knows that.

Maybe he's asleep, I think; he sometimes takes a nap after work. I brush the caked dirt from my knees and walk toward the open garage, where a staircase leads to the kitchen.

As I approach the house, Homey at my heels, I see kids scrambling from a school bus at the corner and construction workers swarming over a building site across the street.

Our neighbor Joe Strykalski is walking his dog.

Gene Nygaard waves from his front lawn, where he's on the cell phone with Karen. She's in North Dakota for the funeral of her father.

As I walk into the garage, I hear nothing but the distant buzz of a sod cutter somewhere out in the April afternoon. I open the door and walk into the kitchen.

It's so fast. A blow catches me from the left, my glasses fly off, and instantly I'm in a blurred world; my eyesight is so poor that without glasses or contacts I can scarcely count the fingers on my hand.

I fall forward through space, almost in slow motion, though the floor seems to rush up at me. I crack my head against the cat food bowl, and water splashes out, and blood splashes out.

My first reaction -- a thought, not quite a thought -- is confusion. What was that? What fell?

I fell. Through the distorted lens of my vision I see someone moving around me. I lift my head and stare up at the dark silhouette of a man. Tan jacket, baseball cap -- I can't see much more. The sunshine in the kitchen creates a weird backlight, glowing from behind him so his big shape looks haloed.

"Where's your money?" he says. This is no voice I've ever heard; the sound of it is deep and quiet, but there's another quality in there, too, something like excitement. Like he's about to tell me a secret.

Fear doesn't happen yet; it's two beats away, or three. I'm stunned, still trying to decide and accept that someone is in the room with me, a stranger who has struck me. Why did he do that? Oh, yes. Money. Hurry. Give it to him.

"My purse. My wallet's in my purse. On the counter by the sink." I don't keep lots of cash on hand. For the first time in my life I'm hoping there's lots of it in there. I know my rings -- my diamond anniversary ring and a diamond pinky ring -- are there, too, along with my watch, where I took them off before gardening.

Take them.

I watch to see him move away. I wait, all my senses tuned up, for the sight and sound of him walking out of the room. But he doesn't go. Blood spreads across the floor, and my head hurts.

"Where's your husband?" he says.

"I don't know." It comes out a whisper.

Nino's an orderly man, a creature of habit whose activities and location can almost always be charted by the calendar and the clock. When he comes home from work most afternoons, he has a snack, lies down for a half hour or so, then goes outside to walk and chat up the neighbors, pacing off the frustrations of his day.

If he went out today, he must have taken the front door leading out onto Oklahoma, the broad drive that leads from the street into our development. Otherwise we would have passed each other in the side yard.

The blow was so strong that I'm senseless on the tile floor, with an odd buzzing inside my head. I feel stupid. I can't put thoughts together so they mean anything.

Something inside says, Move. Run. Do something. I can't. I'm just hunched into myself, arms up around my head where he struck me.

Just go away, I think, and in that instant I am gathered up in his arms.

The basement door opens. Somehow I'm on my feet again. He's prodding at the small of my back, propelling me down the narrow wooden stairs. I'm wobbly, but I manage to stumble down them without tripping.

I notice for the first time that my right hand, held tight against my stomach, is shaking. For a second this surprises me. Then I recognize in a strangely detached way that I must be really scared. This may be the first thing I clearly articulate in my mind: I must be really scared.

At the bottom of the stairs he gives a big shove. I land face first on the concrete floor, so hard that I wonder if I've broken my nose. Whatever fear that was kept at bay by that first stunned feeling now just opens up inside, blossoms, explodes, rushes to every part of me like electricity.

"Now," he says, with that same tense excited voice, "let's do this."

With rough hands he's pulling my sweatpants down, then my panties. Oh, Jesus. Jesus Christ. Not this.

My eyes are wide open and staring. Though very little light comes in -- the basement windows are dusty and set up high -- I can look from side to side and see things. The basement is heaped up with lots of old musical equipment, boxes of old tax records, boxes I marked "summer clothes" and "holiday decorations" and "Mom's dishes" -- twenty-five years' worth of pack rat stuff. The dehumidifier whirs in a corner.

I get intermittent flashes of clarity, lucid thoughts spooling out in front of me like old home movies. We have been here so briefly -- just one Halloween, one Thanksgiving, one Christmas. Improbably, I'm thinking of last Christmas, when, for the first time ever, Nino didn't argue when we got a real tree to fit the fourteen-foot foyer.

Most years he lobbied for an artificial tree ("So clean, so economical"), a notion I resisted with all my might. And on this at least, I always prevailed. No pipe cleaner Christmas tree in my house, no plastic greens and garland. I wanted that good sweet fresh tree smell all around, and though Nino grumbled, he let me have my way.

On that first Academy Hill Christmas, my sister Darlene and her husband, Bill, bought the tree at the local firehouse. When they lugged it in, we all just gaped. It was massive. We made hot cider and ate spice cookies and loaded that tree down with all the decorations we'd collected over the years. My mom's fragile glass ornaments hung alongside things the kids had made at school over the years, gingerbread men made of felt and Popsicle sticks and Elmer's glue. No tinsel, though. Not after the time one of our cats, Kiki, ate a few strands, then walked around the house with most of it hanging out the other end.

Now he is beginning. He is brutal. He's all over me from behind, making low noises as he does it. It goes fast, which is no mercy. I'm so tense I tighten up, and it hurts. When he's through, I'm wet from him and dirty and ashamed of my degradation.

I hear a sound like a little girl's, the kind of sound my Melissa used to make when she was small and scared of something in the night.

"Shut up, bitch," he says, so I know the sound must be coming from me. "Shut up."

Melissa was always afraid of storms, especially the sound of the wind and the sight of everything tossing all around. It made her feel the world was falling down around us. But I reveled in it -- the rain, the wind, the lightning, and the majesty and energy of it all. And when she'd run to me, whimpering, I'd bundle her up on my lap and we'd watch together out the window. "See? It can't hurt you, honey. So hush."

"Shut up, bitch," he says.

Back to the kitchen. We have moved there somehow, and now everything's going fast. The phone rings. Must be four o'clock. I get my daily work assignment at four precisely, no deviation, every single day I'm on call. If I don't call them, they call me. The phone stops, rings again, stops.

Back to the floor. I take another hard landing, smash my nose again, then he's got my arms pulled up behind me. He loops some kind of thin cord around my wrists, over and over. Then something falls over me. It's the flowered quilt from Nino's and my bedroom, which is on the first floor off the dining room.

I'm worried for my husband. I know Nino. If he walks in on this, he'll do anything to defend me and our home, and I don't know if he can win a fight with this man, who is bigger and probably a lot younger.

A part of me is willing him away. Another part is helplessly angry, wondering why he hasn't come to rescue me.

Nino, for God's sake, stay away.

Nino, for God's sake. Come home.

The man walks away. Long minutes pass, ticking off on the kitchen clock. Five minutes. Ten. I listen for anything at all and hear nothing. My breath, which had been coming in short sharp bursts, starts to calm. It's over.

The littlest of our cats, who's old but so tiny and round he still looks like a kitten, comes sniffing around. Paddington sticks his nose under the quilt, and I'm comforted. He's there. The intruder is gone. And now the front door opens, and I know my husband's back.

Breathe.

But no. The tread of these steps is heavy and slow. Not like Nino's steps.

Kitchen drawers open and slam shut, one after the other. What's he looking for? He's going through the cutlery, it sounds like. There is clatter, and it sounds big and violent in my ears. What's he looking for?

When he lifts me, it's like he's carrying something disposable, not a person at all. He takes me into the foyer, and I can hear things from the outside -- construction sounds, traffic -- so I know our front door is open.

"Oh, no. No, no, Jesus. Don't do this."

"Shut the fuck up."

I'm on the floor, on my back this time, and there is a flash of brightness and I see the knife: long sleek blade, fat black handle. He brandishes it so I can see -- like he's going, Look at this! -- then presses the sharp end to my neck, so hard I can feel the point of it piercing my skin.

"Do you want to just shut your fucking mouth?" Then I hear the rip of duct tape.

For nine years, I've worked with people on the cusp of death. Sometimes I'd wonder, couldn't help wondering, how I'd die. With a little prayer going up, I'd think, Please, nothing devastating, none of the cancers. It's so hard on everybody, especially if dying comes too early or lasts too long. I wanted that good death where you live out all your seasons, do most of the things you have planned, last long enough to hold the grandchildren and maybe even the great-grandchildren, then pass softly, like a sheaf of wheat falling before the wind. I have been so idealistic about this, and arrogant, too, thinking I could choose. I believed if I concentrated hard enough, I could create that graceful, good death for myself.

Now I know how the story really ends. I'm going to be murdered.

More than anything else, it's surprise I feel. I never thought of this.

But wait. I need time to prepare. Let me get used to this. Let me figure out a way to do it.

He carries me lightly, effortlessly. Three things are before me, like the snapshots that always crowded the front of our refrigerator, stuck on with smiley-face magnets and cow magnets: Melissa. Michael. Nino.

Still wrapped in my favorite quilt -- it's brand new, I think, in that odd detached way, hoping it doesn't get damaged or dirty -- I'm tossed into the back of his car. I hear every sound as a distinct thing, a warning bell, a death knell, and with every sound I am flooded with disbelief. The hatchback slams. The driver's side door opens and closes. The key turns in the ignition. The engine starts.

I have heard this many times on TV over the years: if you're being attacked, never let yourself be taken to a "secondary crime scene." I remember it now so distinctly, seeing the detective, J. J. Bittenbinder with the big mustache, talking about this onOprah."Do anything you can to keep from being taken from your own environment. Take any risk, do anything you can."

I'd shuddered to hear it, especially when he said it's better to struggle and run and be shot at than to be forced into a car and driven off.

The man eases his car from the front door into the street then pulls slowly away.

Copyright © 2003 by Debra Puglisi Sharp

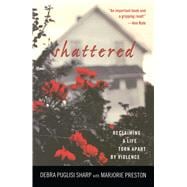

Excerpted from Shattered: Reclaiming a Life Torn Apart by Violence by Debra Puglisi Sharp

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.