Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Preface: First Songs: The hymns of my childhood | p. 1 |

| A Brief History of Hymns | p. 17 |

| Plain Chant | |

| Martin Luther | |

| Isaac Watts | |

| Charles Wesley | |

| William Cowper | |

| Fanny Crosby | |

| Modern praise songs | |

| Simple Gifts: Songs of Simplicity | p. 27 |

| "Simple Gifts" | |

| "He Lives" | |

| "Imagine" | |

| "In the Garden" | |

| "O Holy Night" | |

| "Joy to the World" | |

| "Away in a Manger" | |

| "O Little Town of Bethlehem" | |

| "Jerusalem" | |

| "In the Bleak Midwinter" | |

| Amazing Grace: Songs of Wonder | p. 77 |

| "Amazing Grace" | |

| "Be Thou My Vision" | |

| "How Great Thou Art" | |

| "Just As I Am" | |

| The Prayer of St. Francis: Songs of Love | p. 117 |

| "Make Me a Channel of Your Peace" | |

| "There Is a Balm in Gilead" | |

| "Abide With Me" | |

| Afterword: Only Joy | p. 155 |

| "The Old Rugged Cross" | |

| "Be Still My Soul" | |

| "Faith of Our Fathers" | |

| "Nearer My God to Thee" | |

| "His Eye Is on the Sparrow" | |

| And other hymns | |

| Acknowledgments | p. 163 |

| Select Bibliography | p. 165 |

| Index | p. 167 |

| About the Author | p. 179 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Preface

FIRST SONGS

I treasure some of the grand old hymns. My great joy is to sing them with people like me who hold them deep in their memories and call them forth with passion.

At the nondenominational Rockbound Chapel, fastened to a granite boulder on a hill over the sea near Sedgwick, Maine, I sing songs with other summer visitors -- strangers and people I barely know. In untrained, inelegant, often too-loud or too-soft voices, we sing to each other of our pain, loneliness, and fear, topics we would hesitate to admit flat out in gatherings after services. We also sing of love, grace, trust, hope, peace -- sentiments that are left out of the usual daily patter. We sing words that matter to us.

We are a mixed lot in age, sex, and occupation. We are fishermen, poets, CEOs, clerks, teachers, publishers, builders, mechanics, retirees, holiday rusticators, and others. We sing out our souls for each other. Our hymns are like hugs.

We are Protestants, Catholics, and those who would prefer not to be labeled. Some of us are of troubled faith and others are more agnostic than not. Even if our pew companions don't exactly share creeds, our hymns carry all of us to those Thin Places described by the Irish, elevated states of consciousness where almost all barriers between mortals and gods vanish.

Most of us Rockbound singers, like everybody else, spend portions of our days listening to music on our radios, TVs, or CD players. We are sung at. But in the tiny chapel we find our own voices. It makes no difference how well we sing, only that we do so. We raise our notes to each other and to heaven. No celebrity musician ever receives as much fan-love as we humble amateurs do, from each other, from the spirit within and around us.

My friend Scott Savage, a conservative Quaker, tells me that often hymns "break out." His family's favorite is "The Holy Ghost Is Here," written in 1834 by Charles H. Surgeon. Scott writes: "At the noon prayer before lunch this hymn breaks out, or while we cut up apples for canning applesauce, or on a walk, or returning from meeting, my wife and our two children sing it together unprompted and quite sweetly, while Ned the horse finds his way home."

At the Rockbound Chapel, songs don't break out in quite the same way. We raise our hands before the service and call out the page numbers of cherished songs, while Jim Lufkin, our energetic pastor, scribbles notes and prepares the agenda. After we get rolling, accompanied by a grand older lady, Alice Egland, on the piano -- she knows scores of hymns by heart -- or with the help of a visiting fiddle, flute, or even a saw player, the spirit breaks out in earnest. In an hour we might cover two dozen hymns, first and last verses, sometimes all the verses. Old, old hymns. Never anything modern.

Words, mere words, flat on the page or preached dead in the air, can ruin faith and often divide congregations. Theological niceties spun by divine theorists for centuries have led to ridiculous and murderous quarrels. Are we saved by grace or works? Does God recognize full-body baptism or a sprinkle? On and on the words of dogma spin into an eternity of nonsense.

As Kierkegaard put it rather bluntly: "When a lark wants to pass gas like an elephant, it has to blow up. In the same way, all scholarly theology must blow up, because it has wanted to be the supreme wisdom instead of remaining what it is, an unassuming triviality."

A great preacher can almost lift mere words into the realm of song, but some don't even come close. Their verbiage leaves me annoyed, bored, betrayed, or asleep. During some sermons in various churches, I daydream that I had brought a basket of ripe fruit to lob at the pulpit. Why should I sit here politely listening? I think, gazing out the window at the blowing tree limbs, the rushing clouds, or the tombstones of the blessedly dead.

We forget such sermons as quickly as possible. We also may forget even the words of wonderful sermons. But hymns -- the classic, lasting hymns -- resonate from childhood on. Even those of us who haven't warmed a pew in decades can recall hymns we learned in Sunday School, and in such songs our childhood faith is often restored.

William James observes inThe Varieties of Religious Experience(1902): "In mystical literature such self-contradictory phrases as 'dazzling obscurity' 'whispering silence' and 'teeming desert' are continuously met with. They prove that not conceptual speech, but music rather is the element through which we are best spoken to by mystical truth."

Music is transcendent theology. Hildegaard of Bingen, the twelfth-century mystic and composer, took music so seriously that in one of her plays, while the soul and the angels sing, the devil has only a speaking part. Music has been denied him. Because of his unmelodic nature, he can't approach the Thin Places.

Of course, not all hymns take us there. In fact, some hymns propel us in the opposite direction. They leave us lip-syncing the verses, deflated by trivial or sappy tunes and lyrics, Muzak for the well-fed, somnolent mind. For me, a mediocre hymn is as bad as a lousy sermon, because I am expected to participate in the debacle by at least pretending to sing along. I snap shut the hymnal and stand in silence until the last note relieves the congregation.

But oh! When it hits! When a great old hymn reaches way down inside where you live: then the problem is not shall I sing, but can I manage to sing at all. I choke up and stumble over words and notes. Nothing can mean so much as a classic hymn.

Such hymns go to a source in us beyond our control and leave us overwhelmed with joy and recognition. Suddenly, when words and music combine, I see, as in the tremendous line of "Amazing Grace" -- "I was blind but now I see." On paper that line may not mean much. In song, it's almost more truth than I can bear to express.

I rediscovered such a wallop when I sorted through my father's possessions after he died. In his cellar workshop I came across records he had made of himself and our family singing together.

I remember my dad as a shy and mostly silent man. He almost never expressed extremes of emotion and reproved his three children for excessive enthusiasm. "Don't gush," Pop would say. He spent most of his evenings quietly in the cellar, after working all day for General Electric. In his workshop he constructed wood and mechanical projects: a wagon for my brother and me (the "Bill/Bob"); a crutch for my mother when she fell and broke her ankle; a snow-blower concocted out of an ancient fruit tree sprayer; and the device that allowed him to create these records.

His forty-five-RPM vinyl discs were scratchy and definitely homemade, but on one my father's passion for hymns was obvious. He both sang and accompanied himself on the piano. The record label said "Francis, 1948":

"TAKE TIME TO BE HOLY"

Take time to be holy

Speak often with God

Find rest in Him always

And feed on His word.

Make friends with God's children

Help those who are weak

Forgetting in nothing

His blessing to seek.

His voice was a determined whisper, as if he was embarrassed to be recording himself, but behind that whisper I felt a need that he couldn't express in any other way. In his reserve and shyness he often found it difficult to "make friends with God's children." Here he almost cries out that he wants to do just that.

In another of Pop's recordings, I heard my mother and me in 1946 singing "Jesus Loves the Little Children":

Jesus loves the little children

All the children of the world

Red and yellow, black and white

They are precious in His sight.

And "Jesus Loves Me":

Jesus loves me!

This I know

For the Bible tells me so.

On a record dated "Christmas 1950," I tentatively plunked out my nine-year-old's piano version of "O Little Town of Bethlehem" while my mother encouraged me, "Good, Billy, very good," and Pop stood by with his marvelous machine.

In church, in Sunday School, and at home, we sang together. As World War II ended, the nuclear age began, the Cold War descended, and the Korean War erupted, hymns became our everyday certainty. They lifted us above the world and assured the Henderson children that a greater power than all others protected us in love.

At our church, Philadelphia's Oak Park Fourth Presbyterian, I joined the Junior Choir with my younger brother, Bob. At Christmas and Easter we sang for the congregation. My favorite was "Christ Arose":

Up from the grave he arose

With a mighty triumph o'er his foes

He arose a victor

From the dark domain

And He lives forever

With his saints to reign

He arose! He arose!

Hallelujah! Christ arose!

I loved the imaginary pyrotechnics. There was Jesus low, very low, in the dark domain (whatever that was), and suddenly up he rushed, like a huge whale from the ocean depths, with a great splash as he surfaced and surged upward to the sky.

Since I was the tallest child, I was positioned on the back row in front of the altar on the highest step. Attired in my black and white robe, I could sing to all in the stone church below me. "He arose!" I shouted from my pinnacle, as the whale jetted to the stars. "He arose!"

In grade school I started trumpet lessons and my brother tackled the trombone. One July we serenaded the Wednesday night singers at our little summer church on the outskirts of Ocean City, New Jersey. I remember the bare plank floors, wooden folding chairs, an out-of-tune piano, and a few dozen of the faithful. Our first-ever recital. Bob and I stood in front of the group as the sun set through the windows and the ocean sighed a block away. "Trust and Obey" was our duet, a rather simple hymn. We had practiced it hard and were quite confident. We hit the first few notes OK, lost our place, and stopped dead with stage fright. Finally, after a long silence, we were politely thanked by the minister, who escorted the comatose boys to their seats next to their parents and younger sister, Ruth. The congregation applauded lightly.

"That's all right," said the minister. "God appreciates the effort."

It would be decades before I tried "Trust and Obey" again, and then it would be in a big city, deep in my cups.

Gradually, as I became a teen, church and its hymns lost interest for me. Girls, sports, and scholastic ranking were more important. Pop urged, indeed begged, me to attend services with him and Mom, but I refused. I sang no more hymns.

But I continued to practice the trumpet. It was thought by education pundits that music inoculated kids against juvenile delinquency and made them appreciate the finer things. Music was practical. Plus, said the guidance counselors, trumpet-playing would look good on my permanent record. I would appear "well-rounded" for college admissions (well-rounded was a top virtue of the times). Music was a higher-education insurance policy.

I practiced mightily and progressed to first rank in the junior and senior high school brass sections. In eleventh grade I was named drum major of the Lower Merion High School marching band. In a ridiculous two-foot-tall rabbit fur headpiece, a maroon military uniform and cape, and a long shiny baton, I strode duck-footed onto the halftime football field and blasted my whistle at the musicians under my glorious command. We attempted to entertain the uninterested crowd with our squawking of "Semper Fidelis," "The Thunderer," or "Stars and Stripes Forever." Then we fled the field in ragged lines blaring the school fight song.

I was becoming very well-rounded.

With my brother and a few friends I started a dance band -- the Continentals. Like thousands of boys then and since, we thought music was the key to fame, fortune, and girls. I figured we'd become as famous as the Paul Whiteman band. But Saturday practice sessions often ended quickly as we took up our real interest -- driveway basketball.

We Continentals managed to learn only two songs -- "Beat Me Daddy Eight to the Bar" and "You Always Hurt the One You Love." Our first gig was a Methodist teen dance. Our two tunes lasted only a few minutes. We knew no other tunes. That was it for the Continentals. The minister scrambled around for a record player to fill the void.

Our washed-out school music teachers had long ago lost any zeal for their profession. Years of listening to students butcher the classics had worn them down. They never hinted to me, or they had forgotten entirely, how music could revolutionize heart and soul. However, I was told that a knowledge of classical music was important for college.

I borrowed Beethoven's Fifth Symphony from the library. It was one of the few symphonies I had heard of. I lay on the couch, determined to listen carefully and find out what use this music would be to me. At one point, the theme seems to dissolve as if Beethoven is done with it. Then, as any Beethoven lover knows in his gut, it begins again almost imperceptibly and gathers to a roar of affirmation. Here, I was propelled to my feet in ecstasy. So that's what music can be, I suddenly knew again -- a glimpse from the hymns of my past.

After college, I taught school for a year, wandered around Europe for a few seasons, and returned home to Main Line, Philadelphia when my father died suddenly. I expected to be drafted into the army at any moment and shipped to Vietnam.

While waiting for the summons from the draft board, I worked as a reporter for the local paper, but my real office was Roach and O'Brien's bar, a concrete-block eyesore on Lancaster Avenue, the great eighteenth-century Conestoga wagon route to the West. Over R&O's a large neon arrow pointed inward. Flat out, with no frills, it announced "BAR."

Here I learned what a bender was -- mourning my father, girlfriendless, spiritless, dreading Vietnam. The jukebox serenaded my bar brothers with the top hits, played over and over. Nobody listened. Now and then we looked up at the TV and the latest reports of body counts.

Sometimes on my car radio I would happen upon an evangelist and I'd recognize the rhythm of his sermons and the cry of his songs. I tried to sing but gave up after a few lines.

All I recalled from the church of my childhood was incomprehensible, doctrinal silliness: Life Everlasting, if you believed in Jesus. If not, Eternal Damnation, and that went for billions of people who never had a chance to raise their hands at Billy Graham, Oral Roberts, Jimmy Swaggart, or Carl McIntire revivals. These billions burned forever, as did their ancestors at that moment. Could you hear their screams, the cries of the children? And that probably went for Catholics, too, and certainly for Jews.

Couldn't we talk about this sadism? I wondered, staring at the bottles behind the bar. How could anybody believe this stuff? But there was nobody to talk to.

"Is this God a moron?" I'd ask a bar buddy, who had no opinion, hadn't thought about it, but probably suspected that I sounded subversive and maybe unpatriotic.

Are all these people who believe in this God morons also? I continued the conversation with myself. My father believed all that. Was he maybe insane?

My mother admitted she had doubts about particular doctrines, but she was sure Pop was in heaven now and that she would join him some day. What was I missing here? I sat there watching the beads of moisture run down my beer mug while the Beatles sang "Michelle Ma Belle" on the jukebox for the umpteenth time that morning.

Couldn't God have just sent flowers to let us know of His love instead of making His son into a bloody sacrificial lamb? I pondered.

Booze, that's where love was. Dependable, warm, fuzzy beer-and-a-bump love.

What a difference it would have made if somebody had walked into that dark, stale room and announced to us, "God loves you, I love you. That's what this religion is really all about. Love. The rest is nonsense. Come sing with us."

But nobody ever did.

However, this God business, I discovered, did have practical uses. Divinity students were excused from the draft. I played the religion angle and applied to Princeton Theological Seminary. But when I showed up for the interview, I was too shaky and hungover to make much sense.

Crozer Theological Seminary, where Martin Luther King, Jr., graduated, admitted me with a scholarship. But I was too far gone to attend. Besides, somebody who believed all that stuff could use the scholarship more than I. I wrote to them that I was sick. They replied that they were sorry about my illness and I was welcome to join them when I got better. Crozer really did seem concerned about me personally, I noticed, rather amazed.

When the letter from the draft board arrived, I reported for my physical. But they didn't want me. My shrink informed them I was insufficiently violent and too drunk to shoot straight.

Somehow, in the years ahead, I didn't kill myself with booze.

Then one night at a party, many years later, I began to sing again. I was working as an editor for a New York publisher and although I hadn't received an invitation to this fancy book party, that didn't stop me from oiling up at a nearby bar and making an entrance.

Far across the crowded room I recognized the evangelist Ruth Carter Stapleton, sister of then-president Jimmy Carter, sitting on the sofa, temporarily alone. She was the author of one of the just-published books being celebrated that night -- a biography of her beer-swilling, loose-lipped brother Billy, proprietor of a Plains, Georgia, gas station.

This was a literary crowd. Theodore White, author ofThe Making of the Presidentseries, was the other honored author. Everybody seemed to ignore Ruth, as if she were some sort of born-again freak.

Booze-bold, I strode across the room and, without introduction, plunked myself down hard next to her. Too carefully, I placed my glass on the coffee table in front of us.

"Hi! I'm Bill Henderson," I announced.

"Ruth Stapleton," she smiled.

"I know. I know who you are. You're the only evangelist I've seen for real in person since Billy Graham. Ocean City, New Jersey, 1948. He was in a hall by the boardwalk and you could hear the ocean breaking outside. My dad took me there. He was very religious, believed in faith healing. Billy Graham was just a kid, almost, and very popular. My dad and I sat in the back of the hall and Dad let me sit on the aisle side so I could see straight up to the microphone where Billy spoke."

I stopped for a breath in my rambles.

"Yes?" she smiled, encouraging me.

"You want to hear more?" I stared into her eyes, unsure.

"Certainly."

"My dad was one of the few guys I ever knew who really believed. I mean really, really believed. No doubts. He talked to Jesus all the time. Even on the job. The world around him hardly even existed."

A crowd was pushing out of the dining area and some of the diners came our way.

I found I was holding Ruth's hand. I didn't care what the others thought.

She tightened her grip on my hand, so that I wouldn't pull away. "Tell me more about your dad."

"It seemed like we were the good guys, my dad and I and Billy Graham. I'd heard of the communists but I was only seven years old so I didn't know what all that was, except it was evil. And we were good, and if I looked up I might see Jesus and His angels riding like cowboys across the clouds. Our guys!"

I held her hand tighter. "All those summers in Ocean City, my mom and dad took us to church twice on Sunday, morning and evening. All summer long we sang."

I gazed into Ruth's eyes and began to sing: "Trust and obey, for there's no other way..."

She joined me.

In the midst of that clever mob, we sang:

Trust and obey

For there's no other way

To be happy in Jesus

But to trust and obey.

Nobody paid any attention to us. When we stopped singing, I teared up and couldn't remember the rest of the hymn. I had no more words for her. I leaned over and kissed her on the lips.

Then I knew I was terribly, dangerously drunk and I had to get out of there fast, hopefully without crashing headfirst through the glass table in front of us.

" 'Bye," I managed, and lurched to my feet. I loped through the literati and stumbled down the steps onto the street. Three words began to rearrange themselves in my mind: "If Ruth's God is love, then love is God."

I played with the words. And what is sin? Sin is the withholding of love from others, from yourself, and from God. That's sin. It really had nothing to do with hell and damnation and the only Son of God and the Trinity and all that. This was about love. I was finally beginning to see. And I had started to sing again.

Ruth and I wrote each other in the next year; a few letters filled with her kindness and compassion, but too soon she was dead from pancreatic cancer, and I drifted once again.

In the mid-eighties I married Annie. We had a daughter, Holly, and we lived where we still live -- in a hamlet on the eastern end of Long Island. Down the road from our house is a small Presbyterian church, no bigger than a country storefront, with an old steeple that slants toward the rear as if about to crash down on the congregation.

To Annie, church was ceremony -- songs and stories. She wanted Holly to know these traditions, so she enrolled her in the church Sunday School. But I resisted attending. The idea of walking into a church after decades of absence evoked astonishing dread. Did hell and damnation live there? How annoying that they might try to welcome me back with their Christian grins.

On the night of February 25, 1990, our part of Long Island was entombed by a record blizzard. Not much moved on Sunday morning and the town's plows managed to cut only a narrow lane to the village center past the church.

My usual Sunday morning ritual was a bagel and coffee in bed with theNew York Times. But outside I could see noTimesdelivered on the mounds of snow.

"We're off to church!" Annie announced.

"You can't drive down there!" I yelled.

"Yes, I can!" she called back.

In seconds I reasoned that I had to get hold of aTimesto survive my Sunday in good habit and that I could also chauffeur Holly and Annie safely to church. I'd buy theTimesat the general store, read it there, and pick them up after the service.

But why not go into church, too?

"I'm coming with you!" I hollered to Annie.

Off we spun into the snow.

With Holly and Annie, I walked through the church door into a mostly empty room. The organist was snowed in. Only a dozen people who lived nearby had turned out. The minister carried us in song. Simple, tentative voices muffled by the snow on the roof. Outside it was silent -- not a car, not a crow. We could have been in the Roman catacombs at the very start of it all. No organ propelled us, no piano. We sang as best we could, missing words, mashing notes, but confessing everything to each other in our unadorned voices, as the snow swirled around us.

I don't remember what hymn it was, but suddenly I was gasping for breath, overwhelmed by recognition. In our singing was the love I sought, as we all did. I knew then it was all right for me to be in this little building. Because of that song, and because of my daughter, Holly, singing next to me in her innocence and simplicity, I was back in the church of my father and mother.

Six months later I was a member of the church, and years later I was asked to be an elder and accepted -- a cranky, suspicious-of-cheap-doctrine elder, amazed by my title.

The forgotten hymn has brought me full circle.

What follows is my celebration of classic hymns that have sustained me over the years, and more recently have given me hope -- even joy -- after a diagnosis of serious illness.

There are hundreds of songs that I might have included here, but, as I said at the start, I particularly want to appreciate hymns that I consider to be world hymns -- that do not insist on narrow theologies, but rather love, wonder, and simplicity, my names for God.Copyright © 2006 by Bill Henderson

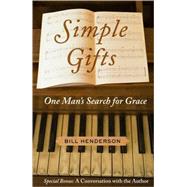

Excerpted from Simple Gifts: One Man's Search for Grace by Bill Henderson

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.