| Introduction | p. 13 |

| Ocean of Wisdom | p. 21 |

| Inside Out: The Dalai Lama Interviewed by Spalding Gray | p. 39 |

| The God in Exile | p. 59 |

| Searching for the Dalai Lama | p. 79 |

| Hope for the Third Millennium | p. 99 |

| Human Rights and Universal Responsibility, The Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama | p. 131 |

| Table of Contents provided by Blackwell. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Ocean of Wisdom

[From Dalai Lama, My Son ]

Almost three years after the birth of Lobsang Samten, I gave birth to Lhamo Dhondup, who was to become the fourteenth Dalai Lama. My husband was bedridden with illness for two months prior to Lhamo Dhondup's birth. If he tried to stand up, he felt giddy and lost consciousness. He told me that each time this happened, he saw the faces of his parents. He could not sleep at night, and this was very difficult because he kept me awake and I had to work during the day. It was thought he was playing a cruel trick on me, but now I know this was not so. It was just one of a series of strange happenings in the three years that preceded the birth.

During that time our horses seemed to go mad, one by one. When we brought them water, they raced for it and then began rolling about in it. They could neither eat nor drink. Their necks stiffened, and finally they could not even walk. All thirteen of them died. It was such a disgrace to the family and a great loss, for horses were money. After this there was a famine for three years. We had not a drop of rain, only hail, which destroyed all the crops. Everyone was at the point of starvation. Families began to migrate, until only thirteen households were left out of forty-five. My family survived solely because the monastery of Kumbum supported us and supplied us with rood. We lived on lentils, rice, and peas that came from their stores.

Lhamo Dhondup was born early in the morning, before sunrise. To my surprise, my husband had gotten out of bed and it seemed as if he had never been sick. I told him that I had a boy, and he replied that this surely was no ordinary boy and that we would make him a monk. Chushi Rinpoche from Kumbum had passed away, and we hoped that this newborn infant would be his reincarnation. We had no more deaths or other strange incidents or misfortunes after his birth. The rains came, and prosperity returned, after years of destitution.

Lhamo Dhondup was different from my other children right from the start. He was a somber child who liked to stay indoors by himself. He was always packing his clothes and his little belongings. When I asked what he was doing, he would reply that he was packing to go to Lhasa and would take all of us with him. When we went to visit friends or relatives, he never drank tea from any cup but mine. He never let anyone except me touch his blankets and he never placed them anywhere but next to mine. If he came across a quarrelsome person, he would pick up a stick and try to beat him. If ever one of our guests lit up a cigarette, he would flare into a rage. Our friends told us that for some unaccountable reason they were afraid of him, tender in years as he was. This was all when he was over a year old and could hardly talk.

One day he told us that he had come from heaven. I had a strange foreboding then, for a month before his birth I had had a dream in which two green snow lions and a brilliant blue dragon appeared, flying about in the air. They smiled at me and greeted me in the traditional Tibetan style: two hands raised to the forehead. Later I was told that the dragon was His Holiness, and the two snow lions were the Nechung oracle (the state oracle of Tibet), showing His Holiness the path to rebirth. After my dream I knew that my child would be some high lama, but never in my wildest dreams did I think that he would be the Dalai Lama.

When Lhamo Dhondup was a little more than two years old, the search party for the fourteenth Dalai Lama visited our home in Taktser. The party included Lobsang Tsewang, a tsedun (government official), Khetsang Rinpoche from Sera monastery (who was later tortured and killed by the Chinese), and others. The first time they visited us was in the eleventh or twelfth month, and it was snowing heavily. There was about four feet of snow on the ground, and we were in the process of clearing it when they arrived. We did not recognize any of them and realized that they must be from Lhasa, but they did not tell us their mission.

They could speak the Tsongkha dialect fluently, for they had been in Tsongkha for three years searching for the Dalai Lama. They had been told that they would find His Holiness in the early morning in a place that was all white. The party stopped at our door and said they were on their way to Sanho but had mistaken the road. They asked me to let them have some rooms for the night. I gave them tea, some of my homemade bread, and dried meat. Early the next morning they insisted on paying me for my hospitality and for the food for their animals. They said good-bye very warmly. After they left, we knew that this was the search party for His Holiness, but it never entered our minds that there was a purpose in their visit to our home.

Three weeks later the party returned to our home. This time they said they were going to Tsongkha, and could we please show them the road. My husband guided them to it himself, and they left. After two weeks they came back a third time. This time Khetsang Rinpoche was carrying two staffs as he entered our veranda, where Lhamo Dhondup was playing. Rinpoche put both staffs in a corner. Our son went to the staffs, laid one aside, and picked up the other. He struck Rinpoche lightly on the back with it, said that staff was his and why had Khetsang Rinpoche taken it. The party members exchanged meaningful looks, but I could not understand a word of the Lhasa dialect they spoke.

I was in the kitchen later, drinking tea on the kang , when Khetsang Rinpoche joined me there. It was easy to converse with him because he could speak both Tsongkha and Chinese fluently. As we sat there, Lhamo Dhondup stuck his hand beneath Rinpoche's heavy fur robes and seemed to tug at one of the two brocade vests he was wearing. I scolded my son, telling him to stop pulling at our guest. He drew a rosary from under Rinpoche's vest and insisted it was his. Khetsang Rinpoche spoke gently to him, saying that he would give him a new one, that the one he was wearing was old. But Lhamo Dhondup was already putting on the rosary. I later learned that this rosary had been given to Khetsang Rinpoche by the thirteenth Dalai Lama.

That evening we were summoned by the party. They were seated on the kang in their room. In front of them were a bowl of candy, two rosaries, and two damarus (ritual hand drums). They offered our son the candy bowl, from which he selected one piece and gave it to me. He then went and sat with them. From a very young age Lhamo Dhondup always sat eye to eye with everyone, never at anyone's feet, and people told me that I was spoiling him. He then selected a rosary from the table and a damaru , both of which, it turned out, had belonged to the thirteenth Dalai Lama.

Our guests offered my husband and me a cup of tea and ceremonial scarves. They insisted that I take some money as their way of thanking me for my hospitality. When I refused, they told me to keep it as a sign of auspiciousness. They said they were looking for the fourteenth Dalai Lama, who they were certain had been born somewhere in Tsongkha. There were sixteen candidates, they said. In truth they had already decided upon my son. Lhamo Dhondup spent three hours with them that evening. They later told me that they had spoken to him in the Lhasa dialect and that he had replied without difficulty, although he had never heard that dialect before.

Later Khetsang Rinpoche drew me aside and, addressing me as Mother, said that I might have to leave my home and go to Lhasa. I answered that I did not want to go, that I could not leave my home with no one to look after it. He replied that I should not say that because I would have to go when the time came. He said not to worry about my home, that if I left, I would live very comfortably and not have any difficulty. He was going to Tsongkha to see the local governor, Ma Pu-fang, to tell him that the Dalai Lama had been born in Tsongkha and that they were planning to take him to Lhasa.

Early the next morning, as they prepared to leave, Lhamo Dhondup clutched on to Khetsang Rinpoche and wept, begging to go along. Rinpoche comforted him, saying he would come back to get him in a few days. Then he bowed and touched his forehead to my son's.

After they met with Ma Pu-fang, they returned once more. This time they said there were three candidates for the Dalai Lama. These three boys had to go to Lhasa, and one would be chosen under the image of Je Rinpoche. Their names would be put in a bowl, they said, and with a pair of gold chopsticks the name would be selected. In fact, they had already decided upon my son. I said again that I could not go, whereupon Khetsang Rinpoche spoke frankly to me, saying that I definitely had to leave for Lhasa. He confirmed that my son was the fourteenth Dalai Lama but told me to keep it to myself.

Four days later four envoys from Ma Pu-fang arrived at our home, took photographs of our house and family, and told us that we were to leave for Tsongkha the next day, on the orders of Ma Pu-fang. I was in the eighth month of my pregnancy and said that I was unable to go. But they told me it was compulsory and important. They said that the families of all sixteen candidates had been summoned.

It took eight hours on horseback to get to Tsongkha. I felt acute discomfort on the journey and had to rest every hour or so. Once in Tsongkha, we were put up in a hotel. My husband and his uncle took my son to Ma Pu-fang's residence. There all the children were told to sit in a semicircle in chairs. The other children cried and refused to let go of their parents' hands, but my son, with great dignity for his young age, went directly to the only vacant seat and settled himself. When the children were offered candy, many of them grabbed handfuls, but my son took one piece, which he immediately gave to my husband's uncle. Ma Pu-fang then asked Lhamo Dhondup whether he knew who he was speaking with. Without hesitation my son replied that the man was Ma Pu-fang.

Ma Pu-fang said that if there was a Dalai Lama, then it was this boy, the brother of Taktser Rinpoche. He said this boy was different, with his big eyes and his intelligent conversation and actions, that he was dignified far beyond his years. He dismissed the other families and told my husband and me that we were to remain in Tsongkha for a few days. For twenty days Ma Pu-fang looked after us and our steeds. On the fourteenth day I gave birth to a baby, who died soon afterward. Each day Ma Pu-fang sent food for us and for the animals, as well as money for daily expenses. He told us to regard him as a friend. He said that we were not ordinary people and were not his prisoners but that we would be going to Lhasa. We were so happy at the news, but our tears were both of joy and of sorrow. I was sad to leave my native land and all that I had known for thirty-five years. With a mixture of apprehension and anticipation I left Tsongkha, for an uncertain future.

I later heard that Ma Pu-fang demanded of the Tibetan government an exorbitant ransom in exchange for the departure of my son. The government complied with his blackmail, only to be met with another ransom demand for more money. This money was borrowed from Muslim traders, who were going on a pilgrimage to Mecca via Lhasa, and who were to accompany us on our journey there. I also heard that Ma Pu-fang was not satisfied with this second ransom and demanded that a hostage of the government be left behind, to be released on news of the safe arrival of His Holiness. The search party therefore left behind Lobsang Tsewang. Later this man escaped from the custody of Ma Pu-fang and returned safely to Lhasa.

Khetsang Rinpoche informed me of all this. My husband and I told Rinpoche that they had made a serious error in telling Ma Pu-fang the truth. They should have told him that we were going on a pilgrimage, and then none of this unpleasantness would have arisen. Rinpoche acknowledged his mistake, but he said it was wiser to have spoken the truth, in case they had been stopped on the journey. I had known Ma Pu-fang since childhood because he was acquainted with my father's two brothers. He had inherited the governorship from his father. China was in upheaval at this time. Civil war between the Kuomintang and the Communists was raging. When the Communists gained control of China, Tsongkha fell to that faction. I heard that Ma Pu-fang escaped to Arabia, where he took up a teaching post.

Finally Ma Pu-fang informed us that we were to leave for Kumbum, where preparations for our journey to Lhasa were being made. He gave us a gift of four swift steeds and a tent and said that if we were in trouble, we must inform him. I had just given birth, and social protocol outside traditional village life demanded that a woman not leave the house until a month after a birth. But my brother-in-law from Kumbum told me that this was a special case, and allowances would be made for me, so it would not be a breach of the moral code.

Six days after the birth of my child (the daughter who died soon thereafter) we left for a stay of three weeks at Kumbum. There I spent my days making clothes for everyone for the journey. Others at the monastery were as busy making preparations.

My husband and I then returned to Taktser one final time, to settle affairs on the farm. Once I got there, I had to prepare grass and fodder for our pack animals and horses. Since most of the route to Lhasa was barren, uninhabited terrain, I had to make ample provisions for the animals. I also packed a lot of Tsongkha tea, chang , vinegar, dates, persimmons, and new clothes for my family. Since the Kumbum monastery was like a home for us, we gave the monks custody of all the important articles from our home. We invited them to say prayers for our oncoming journey, and we invited all our neighbors and relatives for meals, to bid them goodbye. We were soon to leave forever.

Our relatives wept that they might never see us again. We Amdo folk are very emotional and sentimental, and sorrow, except to protect the loved ones at the time of death, is shown by tears. Our relatives journeyed with us for several days, and then they returned to their homes. I wept so much that I was blinded most of the day of our departure. We could not even bid each other farewell, so choked were our voices.

After this we returned to Kumbum. One day two monks came to me and said they had heard some unfortunate news: that Lhamo Dhondup was not the real Dalai Lama, but that it was a boy from Lopon. They said this in order to tease my son. When they left, to my surprise, I found my son in tears, sighing miserably. When I asked him what was the matter, he said that what the two monks had said was untrue, that he was the real Dalai Lama. I tried to comfort him, saying that the monks had been playing a trick on him. After a great deal of assurances he felt better.

I asked him why he was so attracted to Lhasa, and he said that he would have good clothes to wear and would never have to wear torn clothes. He always disliked wearing tattered clothes, and he disliked dirt. If there was even a spot of dust on his shoes, he refused to wear them. Sometimes he deliberately aggravated a tear by tearing it further. I would admonish him, saying I did not have the money to make new clothes for him. He would reply that when he grew up, he would give me a lot of money.

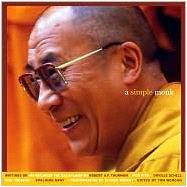

Excerpted from A Simple Monk by . Copyright © 2001 by Tom Morgan. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.