| Acknowledgments | p. vii |

| Map of the American South | p. x |

| The Prologue | p. xiii |

| First Journey | |

| Akbar's Tale | p. 3 |

| Tar Baby | p. 9 |

| Colonel Rod's Tale | p. 20 |

| The Mule Egg | p. 27 |

| Vickie's Tale | p. 34 |

| Rosehill's Tale | p. 48 |

| The Kudzu's Tale | p. 57 |

| Grandfather Creates Snake | p. 62 |

| Orville's Tale | p. 70 |

| Jack and the Varmints | p. 80 |

| David's Tale | p. 92 |

| Ross and Anna | p. 98 |

| Second Journey | |

| Veronica's Tale | p. 109 |

| A Polar Bear's Bar-Be-Cue | p. 110 |

| Taily Po | p. 119 |

| Kwame's Tale | p. 128 |

| The Story of the Girl and the Fish | p. 132 |

| Alice's Tale | p. 139 |

| Cornelia's Tale | p. 158 |

| The Plat-Eye | p. 160 |

| Fouchena's Tale | p. 178 |

| The Flying Africans | p. 189 |

| Minerva's Tale | p. 191 |

| Tom's Tale | p. 200 |

| The Story of Lavinia Fisher | p. 205 |

| Third Journey | |

| Ray's Tale | p. 215 |

| Fourth Journey | |

| Ollie's Tale | p. 237 |

| Kathryn's Tale | p. 248 |

| The Grandfather Tales | p. 254 |

| David Joe's Tale | p. 266 |

| The Peddler Man | p. 269 |

| Karen's Tale | p. 277 |

| Rose and Charlie | p. 289 |

| The Tale of the Farmer's Smart Daughter | p. 296 |

| Oyo's Tale | p. 312 |

| Mitch and Carla's Tale | p. 318 |

| How My Grandma was Marked | p. 326 |

| Wicked John | p. 327 |

| The Bell Witch's Tale | p. 341 |

| Annie's Tale | p. 350 |

| Shug | p. 358 |

| My First Experience with a Flush Commode | p. 360 |

| Angela's Tale | p. 363 |

| Rose Anne's Tale | p. 376 |

| The Song in the Mist | p. 387 |

| Granny Griffin's Tale | p. 400 |

| The Dead Man | p. 401 |

| Index of Stories/Storytellers | p. 413 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

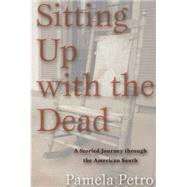

Chapter One

Akbar's Tale

I was wedged into the aisle of the plane, waiting impatiently to exit, when a fellow passenger whispered uncomfortably close to my ear, "They say that when you die, you have to change planes in Atlanta to get to heaven."

Atlanta's Hartsfield International Airport is the second-busiest in the United States. Although it looks like every other airport in the world, the talk there is exceptional. As soon as I arrived in the main terminal, a short, squarish security woman called me "baby," which I found unaccountably comforting (as in "You lost, baby," after I'd attempted to retrieve my luggage from the wrong baggage carousel; my suitcase was doing figure eights on another conveyor belt on the far side of the airport). A few minutes later a very tall African-American man questioned me about cigarettes in Japanese. When I looked confused he switched with great courtesy to chewy-voweled, Georgia English.

The South is a famously talky place. The quintessential Southerner, William Faulkner, wrote, "We have never got and probably will never get anywhere with music or the plastic forms. We need to talk, to tell, since oratory is our heritage ..." Even bones talk sometimes. Even when they're in the ground. There is a story from the South Carolina coast called "The Three Pears," or "The Singing Bones," about a little girl who exasperates her mother by eating pears intended for a pie. Understandably peeved, the mother chops the girl up with an axe and buries the pieces around the farmyard. The head is packed off to the onion patch, which next spring bears a "fine mess" of onions. Sent to pick them, the son hears the ground singing:

Brother, Brother, Brother

Don't pull me hair

Know mama de kill me

Bout the three li' pear

Eventually her bones testify to everyone in the family, and the mother gets so frightened she runs into a tree and dies.

When I first encountered this story I thought, imagine what a ruckus a Southern cemetery would kick up. So many bones prattling on about this and that, you wouldn't be able to hear yourself think. Strangely, this old rural tale is what surfaced in my mind as I was swept out of the Atlanta airport in my new rental car, into a twelve-lane funnel of life moving at top speed. "Such a metaphor," I scribbled on a note pad, risking annihilation as truckers passed me at 80 mph, and Highways 75 and 85 blurred together in a whirlpool of relentless motion. Atlanta is a city on the move, shamelessly advertising America's infatuation with roads and size and moneymaking right in its freeway-bound heart. No time for death here, much less quaint talking bones. If there were any, I felt sorry for them: no one would be able to hear their chants in the din.

Actually, that is not quite true. Atlanta discovered some of its own old bones a few decades ago, and they shout their message -- "Make Money!" -- loud and clear, which is probably why the story came to mind in the first place. In the center of the city is a four-block grotto of unearthed, nineteenth-century cobblestones called Underground Atlanta, excavated and rebuilt as a tourist mecca of glitzy shops and restaurants. These skeletal streets were the foundations of the original city, begun in 1837 and first called Terminus, appropriately enough, for the railroad speculation venture that it was. The district wasn't burned by General Sherman's Union troops in the Civil War; it was buried to make way for a railway aqueduct. What began as a commercial venture died as one, only to be resurrected over a century later on behalf of yet another kind of commerce. It is the Atlanta way.

Those who don't hear the call of money beneath the city chase it toward the sky. Office and shopping towers sprout in clusters throughout the metropolitan area like so many galvanized steel ladders to the future (getting from one to another means that Atlanta residents spend more time commuting in cars than almost all other Americans, each logging around thirty-five miles a day). It is no accident that Tom Wolfe's recent novel, A Man in Full , hinged on the fortunes of a reckless Atlanta speculator who built a skyscraper too high for his wallet. Not so much fiction as parable, Wolfe's story of success-run-rampant tells the tale of the city's recent history. In the 1990s, metropolitan Atlanta saw the greatest population increase in America. It currently consumes fifty acres of forest land per day to pave way for new construction. The city is, in fact, the epicenter of an economic boom so great that if the eleven states of the former Confederacy were lumped together as a separate nation, they could claim the fifth largest economy in the world (equivalent, so I'm told, to Brazil).

This is the "New South" that so many speak of: socially liberal and friendly to big business -- an attractive combination paid for in road congestion, air pollution, and overdevelopment. Yet Atlanta was on the make long before CNN, Coca-Cola, and the 1996 Olympics arrived. It has always been what some are complaining it has now become: a work-ethic driven, live-and-die-by-the-dollar, Northern kind of city, noisy and fast and flush with money.

Atlanta was the first stop on my first trip to the South. Over the course of the summer I planned four separate journeys, with brief rest stops at home in New England in between. I knew that my travels would generously overlap themselves and one another: because I was using storytellers rather than states or cities as my coordinates, I expected to leave a messy trail on the map, but gather a rich earful en route. On this first trip I took Georgia for my base, with forays planned both north and south of the state. The other journeys would take in the eastern seaboard, Appalachia, and "the Deep South," which included Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. More immediately, however, navigating Atlanta was my chief concern.

None of the people behind the desk at the Super 8 Motel in the heart of downtown had ever heard of Ralph David Abernathy Jr. Boulevard, which disturbed me. Abernathy was Martin Luther King, Jr's, right-hand man throughout the civil rights movement. While nearly every town in the South with more than one stop sign has a Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, or at least an Avenue, most of the major cities have named something after Abernathy too, and it's usually a pretty significant street. Atlanta is no exception, but it took two painters suspended on scaffolding in the motel lobby to shout directions down.

"No one's ever asked for Abernathy before," said one of the clerks.

I soon discovered why. Abernathy proved a conduit to Atlanta's West End, an old African-American neighborhood of bungalows with sagging porches, pawn shops, fast-food restaurants, and corner stores hidden behind antitheft grills. Conversational half-circles of chairs were set up here and there on the sidewalks but were all empty: already at 10 A.M. steamy, near-tropical heat had a stranglehold on the day. Here, at last, was a restful nook in the city -- a little ramshackle, but pleasantly quiet. I was no longer surprised it had been so hard to find. This neighborhood was the Atlanta anomaly, more Old South than New, where time was to be had in greater quantities than money.

All the bigger buildings seemed boarded up, except one. Marooned on the shabby street was a well-kept monument to Victorian whimsy: a many-gabled Queen Anne--style cottage with yellow patterned shingles, tall chimneys, and a giddy wraparound porch that looked like a carnival train of painted wagons. This was the Wren's Nest, former home of Joel Chandler Harris, the nineteenth-century newspaper man who gave the world Uncle Remus, and wrote down the Brer Rabbit stories.

I made my way onto the tangled grounds and a teenager named Matthew ran up and shook my hand. He lived nearby and was a summer intern at the house, now a museum. We traded confessions of childhood fears. He'd been afraid of hockey masks because the killer in Friday the Thirteenth had worn one; I'd thought pink paint could only be achieved by mixing white paint with blood, and one day insisted (on pain of sleeping elsewhere) that my room be painted blue. After these confessions we were buddies, and he showed me around the musty Victoriana: a full set of Gibbon in the library, windows shuttered against summer heat, tasseled lamps lit in the gloom, and 31 five-year-olds racing up and down the long, "dog trot" hallway, the electric heels of their Nike sneakers flashing red. The five-year-olds and I had come to listen to Akbar Imhotep, a storyteller who had not yet arrived. While I waited for Akbar, I watched a slide show about Harris' life, slightly unnerved that the rest of the audience consisted of a stuffed bear and rabbit -- both dressed for church -- and a fox in need of a taxidermist's touch-up.

At thirteen, Joel Chandler Harris had been packed off to learn the newspaper trade at Turnwold, the only antebellum plantation in the South to publish its own newspaper. He had spent Saturday evenings there with the owner's children, listening to two elderly slaves tell stories about cunning animals who lived by their wits, sometimes comically, often violently, usually successfully. These were "trickster" tales that had come from Africa with the slaves, and had been adapted over generations into a grand, elastic body of oral literature. Later in life, working for the Atlanta Constitution , Harris hit on the conceit of having a fictional former slave named Uncle Remus recount these stories in a newspaper column, which Harris would write in "darky dialect." Remus became such a hit that Harris collected his stories in 1880 in Uncle Remus: His Songs and Sayings , making both their names -- as well as that of the trickster hero Brer Rabbit -- famous worldwide.

Harris died in 1908. In 1946 Walt Disney Pictures released Song of the South -- the animated musical based on the Uncle Remus tales that brought the world the Oscar-winning song "Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, zip-a-dee-ay, my oh my, what a wonderful day" -- which struck many as paternalistic, at best. For the first time Remus began to look like what he had been all along: a white man's projection of the grandfatherly, accommodating, unthreatening, forgiving jester he wanted all black men to be. Though he never fell out of print, Harris fell out of favor with a thud. In the late sixties Disney withdrew the film from circulation. Then slowly, a decade later, the tide started to turn. Harris's "darky" speech was pronounced authentic African-American dialect; had he not chosen the vessel of Uncle Remus, it was declared he would have been the father of American folklore. As it was, Harris saved a body of oral tales that otherwise might have been lost. Disney released the film again in 1980 and 1986, and has made an estimated $300 million from it to date.

Akbar had arrived, damp with the same summer sweat that had turned my cornflower blue shirt cobalt under the arms. Solid, strong, and rounded all at once: he was a comfortable man to look at, with close-cropped, graying hair and a goatee to match. He swept into Harris's "good" parlor (reserved for company) followed by an unruly wake of black and white children, who settled into a kind of bobbing pool at his feet. I joined them cross-legged on the floor. In his pink and black African-print shirt, flanked by a pair of drums, Akbar seized the Victorian room by its own good taste, setting off a chain-reaction tremble in the drapery tassels, lace curtains, dried-flower arrangements, even a marble-top table, with his seated gyrations. A tall carving of Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox, arm in arm, watched from a corner.

Listening to the slide show in the dark, empty room I had been aware of a white voice condensing and interpreting Harris's life. Now, here in his parlor, where Harris had been too pathologically shy to tell stories even to his own children, a black voice was conjuring new life from the briar patch for the children of strangers.

TAR BABY

One time, old Brer Fox and Brer Bear was out sittin' around in the woods, and they was talkin' about all of the things the rabbit had done to 'em, to make 'em look saaad. Old Fox, he looked at Brer Bear, he said, "You know what, bear? That rabbit, he always was a little bit too sassy for me. You hear me?"

Bear said, "Yay-yuh, I hears you Brer Fox. What we gonna do about it, huh?"

Fox says, "Bear, I don't know about you, but if I ever get my hands on that cotton-pickin' rabbit, I'm gonna take his little whiskers, and nick 'em out one by one."

The bear says, "When you get through with that, hee, hee, hee, you give him to me, so I can just nookie him -- Bam! Boom! -- clean out cold. Let's go get him now."

"No. You wait here till I get back. I gots myself an idea."

As Akbar spoke, my knees ached to stretch out, but I was penned in by cookie-scented children on all sides, effectively stuck in a kind of perceptual briar patch of my own making: a white man's house built with money wrung from the stories of slaves, now administered by a black foundation -- which, word had it, faced an uphill financial battle because of the seesawing of Harris's reputation -- principally visited by white tourists who made their way to an off-the-beaten-track black neighborhood, where, if they were lucky, they could hear a black storyteller spin ancestral tales preserved by the intercession of a white man.

Well, old Fox, he left Bear sittin' there. He went down the road to his house, and he got him a bucket. He got that old bucket and he went on down in the woods and he filled it up with some of that old sticky, yucky, mucky, ooey, gooey tar. And he come back out there to where the bear was waitin' on him. When he got back he showed it to old Bear. Then he went and got some turpentine and he poured that over it, kind of softened it up a little bit. Then he went ahead and stirred it. And when he got it good and stirred up, he started scoopin' it up and shapin' it up, and after a while he shaped up a little old head. He worked up some shoulders, and chest, some arms and some legs, and when he got through with it, it looked just like a little bitty person. Some folks say, a little bitty baby. Y'all got any idea what he might a called it?

Kids: "TAR BABY."

Well, after he got this tar baby thing all shaped up, he knew that he had to catch that old smart rabbit. And he didn't know if this old tar-shaped thing was gonna do it. See, one thing that fox knows about, he knew that little rabbit ain't nobody's fool. So he figured, he gotta dress this thing up to get that old rabbit to stop and be friendly with it.

So he looked around to see what in the world he could dress it up with, and he noticed the buttons on old Bear's jacket. He called old Bear a little closer. The old Bear got close to him and he just, Pluck! Pluck! He snatched off a couple of buttons and he stuck them on the tar baby for eyes. He got him a piece a coal and he stuck that on for a nose. Hee, hee, hee, hee! He went on and shaped up a little old mouth. And, aaah, he squeezed some ears on the side of the head. Hee hee, hee, hee, hee! Hooo-EY! He looked at all the hair on Brer Bear's neck, and he just ... aaaah!!! ... stuck that on top of the tar baby's head. Then he took his jacket off and he wrapped that around it. And to top it off, he got old Bear's straw hat, and he stuck it -- eek! -- right on top of the head.

Now. He knew that if that Rabbit saw this little dressed-up tar baby thing, he was gonna stop and try to be friendly. Then he and old Bear would see what would happen when the tar baby didn't say nothin'. Now, to set the trap, they got that old dressed-up tar baby thing, and they took him out to the big road. And when they got out there, they set it up right by the side of the road, then they went out into the bushes to hide. Now, what I want y'all to know, is that right over there (Akbar points; children all look) on the left corner of the imagination, was a thing called a briar patch ...

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Sitting Up with the Dead by Pamela Petro. Copyright © 2001 by Pamela Petro. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.