Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

PROLOGUE

The tall, mustached Texan on horseback looks like the quintessential cowboy with his Stetson hat, red bandana, dusty boots, and jingly spurs. His sunburned arms and leathery face show the wear and tear of a rugged outdoorsman. But Howard Wooldridge isn’t your typical cowboy. He’s a retired police detective who’s riding across the country to promote a provocative message—legalize marijuana and other drugs.

Wooldridge, then fifty-four, and his trusty, one-eyed mare, Misty, began their journey in Los Angeles in March 2005, and it would end seven months and 3,300 miles later in New York City. With a bedroll and a bag of carrots tied behind the saddle, they clippety-clopped from coast to coast, attracting attention and generating press coverage as they passed through cities and towns. Along the way, they had to contend with rattlesnakes in Arizona and New Mexico, and the blistering summer heat of the Great Plains. With the exception of a few death threats, the folks they encountered were usually friendly and many offered the veteran lawman a meal and a place to stay overnight. “The horse is a wonderful vehicle because people relate to the cowboy cop image,” Wooldridge explained. “Then we start talking politics.”

Another surefire attention-grabber was the T-shirt he often wore, with the slogan:COPS SAY LEGALIZE DRUGS. ASK ME WHY.

During his transcontinental trek, Wooldridge lectured on criminal-justice issues at several colleges and universities. He spoke in a disarmingly folksy “Yes, ma’am” manner as he challenged students and other citizens to rethink their ideas about marijuana prohibition and the war on drugs. Wooldridge discussed his eighteen years as a police officer in Michigan and how he never once received a call for help from a battered housewife or anyone else because of marijuana. Yet Lansing-area cops spent countless hours searching cars and frisking teenagers in order to find some weed when the police could have been addressing far more serious matters.

“Marijuana prohibition is a horrible waste of good police time,” says Wooldridge. “Every hour spent looking for pot reduces public safety.” Based on his experience as a peace officer, he concluded that “marijuana is a much safer drug than alcohol for both the user and those around them . . . Alcohol releases reckless, aggressive or violent feelings by its use. Marijuana use generates the opposite effects in the vast majority of people.” Officer Wooldridge decided to protect and serve the public by focusing on booze-impaired motorists. His efforts earned him the nickname “Highway Howie” and kudos from Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

Wooldridge did not condone or advocate drug use of any kind, but he had enough horse sense to recognize that by banning marijuana the U.S. government “essentially drives many people to drink.” He felt that a substance should be judged by the actual harm it poses to the community. “From a law-enforcement standpoint,” Wooldridge asserted, “the use of marijuana is not a societal problem . . . America needs to end pot prohibition.”

Convinced that the laws against marijuana were a lot wackier than the weed, Wooldridge and several ex-cops formed a group called Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) in 2002. Before long, LEAP would grow into a 40,000-member international organization composed of former prosecutors, undercover narcotics agents, judges, prison wardens, constables, and other disillusioned government functionaries who, after years of toiling in the trenches of a conflict with no conceivable end, had come to view the war on drugs as a colossal failure that fostered crime, police corruption, social discord, racial injustice, and, ironically, drug abuse itself, while squandering billions of tax dollars, clogging courtrooms and prisons, weakening constitutional safeguards, and impeding medical advances. LEAP condemned the war on drugs as America’s longest-running bipartisan folly. Wooldridge called it “the most dysfunctional, immoral domestic policy since slavery and Jim Crow.”

When law-enforcement veterans defect from prohibitionist orthodoxy, their arguments tend to be particularly potent. But Wooldridge understood that LEAP’s views were very controversial. He knew that a long journey lay ahead, literally and figuratively, as he sought, one step at a time, to persuade Americans who had been exposed to years of government propaganda about the evils of marijuana. Many people reject the notion of legalizing drugs on moral and ideological grounds. They see marijuana first and foremost as a dangerous recreational drug, a harbinger of social decay. They believe the oft-repeated claim that smoking grass is a gateway to harder drugs.

The “devil’s weed” has long been a favorite target of U.S. officials who misstate or exaggerate the physical and psychological effects of “cannabis,” the preferred name for marijuana in medical and scientific circles. Although cannabis has a rich history as a medicine in many countries around the world, including the United States, federal drug warriors erected a labyrinth of legal and institutional obstacles to inhibit research and prevent the therapeutic use of the herb. They assembled a network of more than fifty government agencies and waged a relentless campaign against the marijuana “scourge,” a crusade that entailed sophisticated aerial surveillance, paramilitary raids, border patrols, sensors, eradication sweeps, the spraying of herbicides, national TV ads, antidrug classes in schools, and mandatory-minimum prison terms for marijuana offenders, including an inordinate number of black and Latino youth.

In 2005, the year that Wooldridge and Misty hoofed across the states, more than 750,000 Americans were arrested on marijuana-related charges, the vast majority for simple possession. And the tally would continue to grow, irrespective of who was president or which political party was in power. Despite billions of dollars allocated annually to curb cannabis consumption, half of all American adults smoke the funny stuff at some point in their lives. An estimated fifteen million U.S. citizens use marijuana regularly.

Marijuana is by far the most popular illicit substance in the United States, with 10,000 tons consumed yearly by Americans in their college dorms, suburban homes, housing projects, and gated mansions. Pot smoking cuts across racial, class, and gender lines. It has become such a prevalent, mainstream practice that cannabis users are apt to forget they are committing a criminal act every time they spark a joint.

The history of marijuana in America has long been a history of competing narratives, dueling interpretations. As Harvard professor Lester Grinspoon, M.D., observed in his 1971 bookMarihuana Reconsidered,some “felt that the road to Hades is lined with marihuana plants” while others “felt that the pathway to Utopia was shaded by freely growingCannabis sativa.” And so it continues. At the center of this dispute is a hardy, adaptable botanical that feasts on sunlight and grows like a weed in almost any environment. Marijuana plants are annuals that vary in height from three to fifteen feet with delicate serrated leaves spread like the fingers of an open hand. Ridged down the middle and diagonally veined, cannabis leaves are covered, as is the entire plant, with tiny, sticky hairs. The gooey resin on the leaves and matted flower tops contains dozens of unique oily compounds, some of which, when ingested, trigger neurochemical changes in the brain. The hotter and sunnier the climate, the more psychoactive resin the plant produces during a three-to-five-month outdoor growing season. Known for its euphoria-inducing properties, “hashish” or “kif” is the concentrate made from the resin of female marijuana.

Ancient peoples during the Neolithic period found uses for virtually every part of the plant, which has been cultivated by humans since the dawn of agriculture more than 10,000 years ago. The stems and stalk provided fiber for cordage and cloth; the seeds, a key source of essential fatty acids and protein, were eaten as food; and the roots, leaves, and flowers were utilized in medicinal and ritual preparations. A plant native to Central Asia, cannabis figured prominently in the shamanistic traditions of many cultures. Handed down from prehistoric times, knowledge of the therapeutic qualities of the herb and the utility of its tough fiber slowly spread throughout the world, starting from the Kush, the herb’s presumed ancestral homeland in the Himalayan foothills. The plant’s dispersal across Eurasia into northern Europe followed the extensive migratory movements of the Scythians, aggressive charioteers in the second millennium BC. A famous passage in Herodotus’Histories(440 BC) refers to Scythians “howling with pleasure” in their hemp vapor baths.

Details gleaned from various academic disciplines—archaeology, history, anthropology, geography, botany, linguistics, and comparative mythology—indicate that marijuana’s historical diffusion proceeded along two divergent paths, reflecting its dual role as a fiber crop and a psychoactive flower. One path moved westward from China into northern Europe, where cooler climes favored rope over dope, while the other path, the psychoactive route, hewed to trade lines that swung southward into India, Persia, the Arab Middle East, and Africa. As it traveled from region to region, the pungent plant never failed to ingratiate itself among the locals. Something about the herb resonated with humankind. Once it arrived in a new place, cannabis always stayed there—while also moving on, perpetually leaping from one culture to another.

Recent archaeological findings confirm that marijuana was used for euphoric as well as medicinal purposes long before the birth of Christ. In 2008, an international research team analyzed a cache of cannabis discovered at a remote gravesite in northwest China. The well-preserved flower tops had been buried alongside a light-haired, blue-eyed Caucasian man, most likely a shaman of the Gushi culture, about twenty-seven centuries ago. Biochemical analysis demonstrated that the herb contained tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive ingredient of marijuana. “To our knowledge, these investigations provide the oldest documentation of cannabis as a pharmacologically active agent,” concluded Dr. Ethan Russo, lead author of the scientific study. “It was clearly cultivated for psychoactive purposes” rather than for clothing or food.

The first reference to the medicinal use of cannabis also dates back to 2700 BC. It was subsequently recorded in thePen Ts’ao Ching,the pharmacopeia of Emperor Shen Nung, the father of traditional Chinese medicine. Credited with having introduced the custom of drinking tea, Shen Nung recommended “ma” (marijuana) for more than a hundred ailments, including “female weakness, gout, rheumatism, malaria, constipation, beri-beri, and absent-mindedness.” Shen Nung called “ma” one of the “Supreme Elixirs of Immortality.” “If one takes it over a long period of time, one can communicate with spirits, and one’s body becomes light,” thePen Ts’ao Chingadvises. When consumed in excess, however, it “makes people see demons.” Chinese physicians employed a mixture of cannabis and alcohol as a painkiller in surgical procedures.

In India, cannabis consumption had long been part of Hindu worship and Ayurvedic medical practice. According to ancient Vedic texts, the psychoactive herb was “a gift to the world from the god Shiva”—where the nectar of immortality landed on earth, ganja sprang forth. Longevity and good health were attributed to this plant, which figured prominently in Indian social life as a recreant, a religious sacrament, and a household remedy. Hindu holy men smoked hashish and drank bhang (a cannabis-infused cordial) as an aid to devotion and meditation. Folk healers relied on ganja, “the food of the gods,” for relieving anxiety, lowering fevers, overcoming fatigue, enhancing appetite, improving sleep, clearing phlegm, and a plethora of other medical applications. Cannabis flower tops were said to sharpen the intellect and impel the flow of words. “So grand a result, so tiny a sin,” the Vedic wise men concurred. There are no less than fifty Sanskrit and Hindu names for cannabis, all praising its attributes.

It’s been said that language reflects the soul of a people. Eskimos have dozens of words for snowflakes, which underscores the centrality of snow in Inuit culture. So, too, with cannabis nomenclature: The versatile herb has generated an abundance of terms in many languages.

Cannabis comes from the Greek wordKannabis,which is related to the Sanskrit rootcanna,meaning “cane.” In the Old Testament,kanna-bosm(Aramaic for “fragrant cane”) is identified as an ingredient of the holy anointing oil, a topical applied by Hebrew mystics and early Christian healers. Galen, the influential Greek physician (second century AD), wrote of the medicinal properties ofkannabis,but also noted that the herb was mixed with wine and served at banquets for pleasure. The first botanical illustration of the plant in Western literature appears in a Byzantine manuscript (AD 512) of Dioscorides, whoseMateria Medicais the foundation for all modern pharmacopeias; he recommended covering inflamed body parts with soaked cannabis roots. Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who laid the foundations for modern plant taxonomy, christened itCannabis sativain 1753.

Hemp, the common English name for cannabis through modern times, usually refers to northern varieties of the plant grown for rope, paper, fabric, oil, or other industrial uses. It derives from the Anglo-Saxonheneporhaenep. Differences in climate account for the paucity of hemp’s resinous secretion compared with its psychoactive twin closer to the equator.

Of the multitude of terms associated with the cannabis plant,marijuanais the most universally recognized and widely used within the English-speaking world (even though it is not actually an English word).Marijuanais a Spanish-language colloquialism of uncertain origin; it was popularized in the United States during the 1930s by advocates of prohibition who sought to exploit prejudice against despised minority groups, especially Mexican immigrants. Intended as a derogatory slur, “marihuana”—spelled with ajorh—quickly morphed into an outsized American myth.

Slang words for marijuana in English are legion—grass, reefer, tea, pot, dope, weed, bud, skunk, blunt, Mary Jane, spliff, chronic, doobie, muggles, cowboy tobacco, hippie lettuce. . . And there are nearly as many terms for getting high, stoned, buzzed, blitzed, medicated. One could fill dictionaries with the shifting jargon related to cannabis. The profusion of idiomatic expression is in part an indication of the plant’s unique allure as well as the perceived need for discretion and code words among users of the most sought-after illegal commodity on the planet. According to a 2009 United Nations survey, an estimated 166 million people worldwide—one in every twenty-five people between the ages of fifteen and sixty-five—have either tried marijuana or are active users of the herb.

Today, there is scarcely any place on earth that cannabis or its resinous derivatives are not found. A cannabis underground thrives from Greenland to Auckland to Tierra del Fuego. What accounts for marijuana’s broad and enduring appeal? Why do so many people risk persecution and imprisonment to consume the forbidden fruit? Does cannabis cast an irresistible spell that bewitches its users? Is the herb addictive, as some allege? What happens when a society uses marijuana on a mass scale?

It is difficult to generalize about cannabis, given that its effects are highly variable, even in small doses. When large doses are imbibed, all bets are off. Marijuana can change one’s mood, but not always in a predictable way. Immediate physiological effects include the lowering of body temperature and an aroused appetite. Flavors seem to jump right out of food. Realms of touch and taste and smell are magnified under the herb’s influence. Quickened mental associations and a robust sense of humor are often accompanied by a tendency to become hyperfocused—“wrapped in wild observation of everything,” as Jack Kerouac, the Beat scribe, put it. Similarly, Michael Pollan touted the “italicization of experience” that cannabis confers, “this seemingly virginalnoticingof the sensate world.”

There are detailed descriptions of the marijuana experience in literature that attest to the herb’s capriciousness, its tricksterlike qualities. A cannabis-induced altered state can be calming or stimulating, soothing or nerve-racking, depending on any number of factors, including an individual’s personality and expectations. Many people enjoy the relaxed intensity of the marijuana high; some find it decidedly unpleasant. It can make the strange seem familiar and the familiar very strange. Marijuana delinks habits of the mind, yet chronic use of the herb can also be habituating.

The marijuana saga is rife with paradox and polarity. It is all about doubles, twins, dualities: fiber and flower, medicine and menace, sacrament and recreant, gift and commodity. The plant itself grows outdoors and indoors. It thrives under a diurnal or a twenty-four-hour light cycle. It can be male or female, single-sex or hermaphroditic, psychoactive or nonpsychoactive. There are two principal types of cannabis—sativasandindicas.Recent scientific discoveries show that there are two sets of G-coupled protein receptors in the human brain and body that respond pharmacologically to cannabis. Marijuana’s therapeutic mechanism is bimodal; it acts upon both the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system, an unusual combination for a drug. Cannabis has biphasic properties, triggering opposite effects depending on dosage. As a healing herb, it is ancient as well as cutting-edge. It has been used as a curative and a preventive medicine. It is both prescribed and proscribed.

Cannabis has always lived a double life, and this also holds true for many marijuana smokers. An escape for some and a scapegoat for others, marijuana embodies the double-edged nature of thepharmakon,the ancient Greek word that signifies both remedy and sacrificial victim. Extolled and vilified, the weed is an inveterate boundary-crosser. Officially it is a controlled substance, but its use proliferates worldwide in an uncontrolled manner. It is simultaneously legal and illegal in more than a dozen U.S. states that have adopted medical-marijuana provisions.

California led the way in 1996, when voters in the Golden State broke ranks from America’s drug-war juggernaut and approved Proposition 215, the landmark ballot measure that legalized cannabis for medicinal purposes. It’s been an ugly, fractious battle ever since, as the federal government, working in tandem with state and local law-enforcement officials, responded to the medical-marijuana groundswell by deploying quasi-military units against U.S. citizens, trashing homes, ripping up gardens, shutting down cannabis clubs, seizing property, threatening doctors, and prosecuting suppliers. Much more was at stake than the provision of a herbal remedy to ailing Americans.

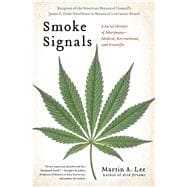

Smoke Signalsis a cautionary tale about U.S. government corruption and constitutional rights under attack. It tells the story of several exemplary characters who struggled against heavy odds, a David-versus-Goliath chronicle in which resolute citizens challenged powerful vested interests and deeply entrenched policies. This book also draws attention to underreported scientific breakthroughs and addresses serious health issues that affect every family in America, where popular support for medical marijuana far exceeds the number of those who actually use the herb.

The wildly successful—and widely misunderstood—medical-marijuana movement didn’t appear overnight. It was the culmination of decades of grassroots activism that began during the 1960s, when cannabis first emerged as a defining force in a culture war that has never ceased. In recent years this far-flung social movement has morphed into a dynamic, multibillion-dollar industry, becoming one of the phenomenal business stories of our generation. The marijuana story is actually many stories, all woven into one grand epic about a remarkable plant that befriended our ancestors, altered their consciousness, and forever changed the world in which we live.