Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

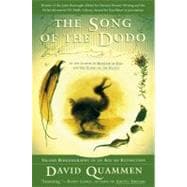

Looking to rent a book? Rent The Song of the Dodo Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions [ISBN: 9780684827124] for the semester, quarter, and short term or search our site for other textbooks by Quammen, David. Renting a textbook can save you up to 90% from the cost of buying.

David Quammen was born in 1948, near the outskirts of Cincinnati, Ohio, and spent much of his boyhood in an eastern deciduous forest there. His interest in the natural world -- hiking through woods, grubbing in creeks, collecting insects, taking reptiles hostage and calling them pets -- was so all-consuming that he would eventually, during adolescence, need remedial training in basketball.

At an early age he learned the word herpetologist and decided he might like to be one. But he had always been interested in writing; and at the age of 17, he met Thomas G. Savage, a Jesuit priest. Savage was to become a life changing teacher, fostering Quammen's literary ambitions and prospects, and encouraging him to attend college at Yale. He knew that at Yale Quammen would find a superb English department, and encounter people such as Robert Penn Warren, a great American novelist, poet, and critic. Despite his not having heard of Penn Warren, Quammen followed the priest's advice and enrolled at Yale. Fools luck was smiling on him, as were generous and trusting parents, and three years later he found himself studying Faulkner at the elbow of Mr. Warren, who became not just his second life changing teacher but also his mentor and friend. Quammen never forgot Thomas Savage's encouragement: The Song of the Dodo is dedicated to this vast-hearted curmudgeon, who died young in 1975.

In 1970, Quammen published his first book, a novel titled To Walk the Line, which had been steered toward daylight by Mr. Warren. Also that year, he began a two-year fellowship at Oxford University, England, where he continued studying Faulkner, loathed the climate, loathed the food, loathed the vestiges of upper-class snobbery, met a few wonderful people, and spent much of his time playing basketball (the remedial training had helped) for one of the university teams. Promptly after Oxford, Quammen moved to Montana, carrying all his possessions in a Volkswagen bus to this state in which he had never before set foot. The attractions of Montana were 1) trout fishing, 2) wild landscape, 3) solitude, and 4) its dissimilarity to Yale and Oxford. The winters are too cold for ivy.

Quammen made his living as a bartender, waiter, ghost writer, and fly-fishing guide until 1979. Since then he has written full time. In 1982 he married Kris Ellingsen, a Montana woman even more devoted to solitude than he is.

His published work includes two spy novels (The Zolta Configuration, The Soul of Viktor Tronko), a collection of short stories about father-son relationships (Blood Line), two collections of essays on science and nature (Natural Acts, The Flight of the Iguana), several hundred other magazine essays, features, and reviews, as well as The Song of the Dodo. From 1981 through 1995, he wrote a regular column about science and nature for Outside magazine, and in 1987 received the National Magazine Award in Essays and Criticism for work that appeared in the column. In 1994 he was co-winner of another National Magazine Award. In 1996 he received an Academy Award in literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He remains a Montana resident, despite the arrival of cappuccino.

In 1998 Scribner will publish Strawberries Under Ice, a new collection of Quammen's magazine essays and features, subtitled "Wild Thoughts from Wild Places." The wild places in question, from which he has drawn observations and inspiration in recent years, include Tasmania, southern Chile, Madagascar, the Aru Islands of eastern Indonesia, Los Angeles, suburban Cincinnati, and of course, Montana.

Reading Group Discussion Points

Other Books With Reading Group Guides

CONTENTS

I Thirty-Six Persian Throw Rugs

II The Man Who Knew Islands

III So Huge a Bignes

IV Rarity unto Death

V Preston's Bell

VI The Coming Thing

VII The Hedgehog of the Amazon

VII The Song of the Indri

IX World in Pieces

X Message from Aru

GLOSSARY

AUTHOR'S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOURCE NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

THIRTY-SIX PERSIAN THROW RUGS

Let's start indoors. Let's start by imagining a fine Persian carpet and a hunting knife. The carpet is twelve feet by eighteen, say. That gives us 216 square feet of continuous woven material. Is the knife razor-sharp? If not, we hone it. We set about cutting the carpet into thirty-six equal pieces, each one a rectangle, two feet by three. Never mind the hardwood floor. The severing fibers release small tweaky noises, like the muted yelps of outraged Persian weavers. Never mind the weavers. When we're finished cutting, we measure the individual pieces, total them up -- and find that, lo, there's still nearly 216 square feet of recognizably carpetlike stuff. But what does it amount to? Have we got thirty-six nice Persian throw rugs? No. All we're left with is three dozen ragged fragments, each one worthless and commencing to come apart.

Now take the same logic outdoors and it begins to explain why the tiger,Panthera tigris,has disappeared from the island of Bali. It casts light on the fact that the red fox,Vulpes vulpes,is missing from Bryce Canyon National Park. It suggests why the jaguar, the puma, and forty-five species of birds have been extirpated from a place called Barro Colorado Island -- and why myriad other creatures are mysteriously absent from myriad other sites. An ecosystem is a tapestry of species and relationships. Chop away a section, isolate that section, and there arises the problem of unraveling.

For the past thirty years, professional ecologists have been murmuring about the phenomenon of unraveling ecosystems. Many of these scientists have become mesmerized by the phenomenon and, increasingly with time, worried. They have tried to study it in the field, using mist nets and bird bands, box traps and radio collars, ketamine, methyl bromide, formalin, tweezers. They have tried to predict its course, using elaborate abstractions played out on their computers. A few have blanched at what they saw -- or thought they saw -- coming. They have disagreed with their colleagues about particulars, arguing fiercely in the scientific journals. Some have issued alarms, directed at governments or the general public, but those alarms have been broadly worded to spare nonscientific audiences the intricate, persuasive details. Others have rebutted the alarmism or, in some cases, issued converse alarms. Mainly these scientists have been talking to one another.

They have invented terms for this phenomenon of unraveling ecosystems.Relaxation to equilibriumis one, probably the most euphemistic. In a similar sense your body, with its complicated organization, its apparent defiance of entropy, will relax toward equilibrium in the grave.Faunal collapseis another. But that one fails to encompass the category offloralcollapse, which is also at issue. Thomas E. Lovejoy, a tropical ecologist at the Smithsonian Institution, has earned the right to coin his own term. Lovejoy's isecosystem decay.

His metaphor is more scientific in tone than mine of the sliced-apart Persian carpet. What he means is that an ecosystem -- under certain specifiable conditions -- loses diversity the way a mass of uranium sheds neutrons. Plink, plink, plink, extinctions occur, steadily but without any evident cause. Species disappear. Whole categories of plants and animals vanish. What are the specifiable conditions? I'll describe them in the course of this book. I'll also lay siege to the illusion that ecosystem decay happens without cause.

Lovejoy's term is loaded with historical resonance. Think of radioactive decay back in the innocent early years of this century, before Hiroshima, before Alamogordo, before Hahn and Strassmann discovered nuclear fission. Radioactive decay, in those years, was just an intriguing phenomenon known to a handful of physicists -- the young Robert Oppenheimer, for one. Likewise, until recently, with ecosystem decay. While the scientists have murmured, the general public has heard almost nothing. Faunal collapse? Relaxation to equilibrium? Even well-informed people with some fondness for the natural world have remained unaware that any such dark new idea is forcing itself on the world.

What about you? Maybe you have read something, and maybe cared, about the extinction of species. Passenger pigeon, great auk, Steller's sea cow, Schomburgk's deer, sea mink, Antarctic wolf, Carolina parakeet: all gone. Maybe you know that human proliferation on this planet, and our voracious consumption of resources, and our large-scale transformations of landscape, are causing a cataclysm of extinctions that bodes to be the worst such event since the fall of the dinosaurs. Maybe you are aware, with distant but genuine regret, of the destruction of tropical forests. Maybe you know that the mountain gorilla, the California condor, and the Florida panther are tottering on the threshold of extinction. Maybe you even know that the grizzly bear population of Yellowstone National Park faces a tenuous future. Maybe you stand among those well-informed people for whom the notion of catastrophic worldwide losses of biological diversity is a serious concern. Chances are, still, that you lack a few crucial pieces of the full picture.

Chances are that you haven't caught wind of these scientific murmurs about ecosystem decay. Chances are that you know little or nothing about a seemingly marginal field called island biogeography.

Copyright © 1996 by David Quammen

Excerpted from The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions by David Quammen

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.