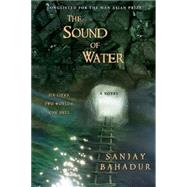

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter 1

It is comfortable in the tombdark womb of the earth. Two hundred and fifty feet beneath the arid crust, it is quiet and cool -- the charcoal silence broken only by the faint rustle of water slithering down the flakywhite walls and pitchdark ceiling. Raimoti pauses to listen. Nothing. He has strayed a little distance away from his gang of six coal diggers enjoying their well-earned dinner break at the coal face. Raimoti strains his ears, craning his wrinkled neck to catch the faintest whisper. He is seeking the sound of water: not the harmless pearl-drop tinkle but the deathly murmur of little waves lapping against the lean barrier of rocks. Today there is just the dry stone, no water. Only shadow under the black rock.

For almost a century, his father and his father's father before that -- all miners -- had lived dreading the sound and died in peace. For close to forty years Raimoti has continued their quest, but the Beast still eludes him. He hopes only to die like his forefathers on the surface, in a dry bed. He fears the Beast and wants to hunt it down before it hunts him out. He fears death by water. He fears being immersed and immured for eternity, within the dark labyrinth beneath the earth where even his gods wouldn't look for him. But he is a brave man, and so he hunts.

He doesn't look like much of a hunter as he crouches, worried, on the mine floor. He has a face that is of indeterminate age but is of someone no longer young. A web of deep wrinkles trickles down from his bony forehead and runs as lost rivulets across his crusty skin and along the corners of his mouth, collecting in shadowy puddles around his protuberant eyes and the hollows of his cheeks. His thinning hair is more gray than black and stands in erratic spirals on an elongated head, giving him a slightly startled look. Reality surprises Raimoti. And his eyes carry a wonderment that comes from questioning the sun and accepting the moon. From doubting light and believing in shadows.

No one, not even his long-dead mother, has ever found Raimoti handsome, but his face has a certain charm that frankness and simplicity bestow on people with uncomplicated hearts. Crooked, tobacco-stained teeth jostling behind his lips add to his bemused expression and are often responsible for luring people into believing that he can be pushed. His crumpled, large ears are a prominent feature of his face. They jut out from the sides of his head as he swivels them in his surreptitious quest for sounds: flat sounds, sharp sounds, dry sounds, wet sounds, colored sounds, white sounds. Black sounds. Sounds within. And from the world outside. His ears soak them all up and interfere with his heartbeats.

Raimoti peers dimly through the shadows and leans closer to the walls of the mine. His long and rough hands grope at the bumpy surface of the tunnel, feeling its coolness. He wipes some dust off with the tips of his fingers and sniffs at it with quivering nostrils. Sometimes soul can hide inside the body, but uttered words can reveal its nature. Sometimes water can hide inside dull rocks but is betrayed by restless dirt that can carry scents. But today the coal dust is sullen and silent -- resisting questions, yielding no secrets. At times earth can be unresponsive like this.

He turns on his heels and squats on his haunches, leaning his tired back against the wall, his thin forearms resting on his knees. Working underground is hard on the body and harder on the mind. It rapidly eats away youth, drains energy, and corrodes thoughts. In some worlds, a man may reach his prime after half a century of existence, but in this one at that age, the only thing that remains is a man's spirit -- and often not even that. Raimoti sighs. He feels too old but has some fight left in him yet. All his life, winning hasn't mattered, because he has been saving himself up for the one confrontation that he knows he is destined to have. He knows it will happen. He just doesn't know how soon.

He turns his head to one side -- away from the light. For a moment he thinks that he caught a glimpse of a sudden movement. After a few seconds, he lets out his breath, realizing that he held it for too long. He stands up slowly and arches his back to get rid of the dull ache that never seems to leave him nowadays. It wasn't so in his youth. He turns to take a look at the far end of the tunnel and decides there is time for a little more exploration.

As he enters deeper darkness, Raimoti clicks on his headlamp. A pale wisp of light emerges and wafts ahead of him, creating shapes that need interpreting, and throws lifelessness into sharp relief: pilings, rivets, roof wedges, rusted rails, debris of abandoned implements, and of course, unpredictable boulders of coal. They grow wild in the mines.

None of these is going to talk to him. He has to find his own answers. The deeper he goes, the more solid the shadows around him become. Silence creeps in from all sides and screams around his ears, making him even more edgy. Only his nose unearths a new fact: a faint smell of death that wasn't there till yesterday. He has known for long that the rocks in this part of the mine are ailing. They do not have long to live. But he had not expected that the end would come so soon or so suddenly. In here there is too little hope to feed them, and almost no happiness, and coal is delicate and vulnerable to melancholia, which abounds in this mine.

Raimoti believes in exhausting all possibilities before giving up, so over the last few weeks, he tried to talk about it to the supervisor and warn him, but no one pays much attention to what he says these days. Dejected, he tried to get assigned to another mine, but the manager did not want to talk to him. This mine and the men working in it are different. Men are not assigned to this mine. They are condemned to work here.

Anyone entering this mine can sense a life-sapping shroud falling over his mind, sucking out positive thoughts and suffocating aspirations. The men working in here are all hand-picked by the company for special treatment. Every day these fading men wear their faded blues and reluctantly descend into the unrelenting depths of this mine -- running away from the despairing emptiness of their lives above and toward the anesthetic hardness of coal below. Inside, they drill, hammer, dig, scrape, heave, and haul. They do things to unresisting rocks that they cannot do to people they leave behind on the surface. They exhaust themselves so that when they return to the world above, they carry less weight on their minds. Over time, some start losing bits of their souls to the underground. They deal with this by drinking. They drink hard so they can go down the next day, and then they drink harder after surviving one more day underground. They drink because they are lost on the surface, and they drink because they cannot find peace underground. This is not a place to exist. And it is a worse place to die.

Mine Number 3 is the oldest operational mine in the Area, dug open about a decade ago. It is quiet down here because the mine has been nearly abandoned. The machines are all gone. The drills, the trolleys, the fancy side-dumping loaders have long been shifted to the newest coal seam opened by the company. Even most of the men have gone. Only a handful of miners and foremen remain to work in the remotest corners, the darkest alleys, and the least accessible crevices of the mine, to extract the last pound of flesh from the earth. The clever young engineers have fine-carved the pillars to the last possible millimeter of the statutory twenty meters, in the hopes of maximizing the corporate goal of optimum offtake or production volume. The face has been taken to the extremes, leaving just a few holes where they want to extract a few more tons of the mineral. For this, they have deployed the "least productive" miners and supervisors: those too old or too young to be useful in the newer mines. There are also some known troublemakers -- insubordinate men who have dared think of themselves as equals of the charmed executives, yet who have continued to stay unaffiliated with the labor unions. They are all dregs. Expendable.

Raimoti is aware of this. He has lived all his life in coal mines. He knows how things work here, below the surface, away from the prying eyes of humanity. In his life, he has replaced many a miner lost to age, injury, or death. He has learned to accept the inevitable. In this dark and remorseless world, there are no winners or losers. There are only survivors. At first the machines were to aid men; now men toil to serve the machines. He knows that in a few months, as soon as he attains the officially acknowledged age of fifty-five, he will quietly be asked by the company to opt for voluntary retirement. He is nearing the end of the tunnel. He doesn't mind that -- he knows that the company has been fooled, just as his father intended. At least he will see daylight for the rest of his days.

Raimoti stops walking when he reaches an intersection. He realizes that the light from his headlamp is adding nothing to his vision, so he turns it off and stands still with his eyes shut, trying to see what eyes cannot reveal. The veil of darkness first breaks into narrow strips and then disintegrates into strands, allowing concentric circles of radiance to wash over him in ripples. He abandons himself to the warmth of that glow and drifts through space, time, and memories. He does this often. It soothes him as his mind floats across the surrounding harshness of life toward the seductive sponginess of nostalgia. Slowly, the pervading stench of dying rocks gives way to a fertile fragrance of wishful thoughts.

He is a small child nestled against the comfort of his mother's breasts. He cannot make out her face, but he can feel the love behind her smile and hear the soft murmurings of affection in his big ears. She smells of moist earth after the first showers of the monsoon. When he is a little older and they walk on dewy grass while she holds his fingers, he can feel the hidden pulse in her palm. It is all so real that he begins to believe it must have been true. He believes that at some point in life, he must have been truly loved -- that he was happy.

Another strand of darkness snaps, and he is sprinting through paddy fields chasing a giant who must be his father. The giant looks back and waits for the little boy to catch up. Raimoti feels a thrill as his father lifts him clear off the green ground and places him on wide shoulders. He feels the flutters of flying birds and the moist caress of the clouds in heaven as he straddles his father's back, his head touching the blue sky. God! He thinks. Can there be a greater joy?

Under the mining helmet, Raimoti's face acquires the hint of a smile. He squeezes his eyelids together with greater determination, hoping to force some more flowers out of a dead ground.

This time he is a young boy sitting under a tamarind tree, listening with rapt attention to a man singing to a god. The boy feels a bubble riding up his throat and bursting from his open lips.

In that silent corridor, Raimoti's voice rings out loud and bounces off the rocks. He knows it can't reach the heavens, but still, it pleases him. He sings out another line and waits for the ricochet. It doesn't come. He sings another line -- this time more softly, warily, afraid to disturb the impassive stones. But the walls are unresponsive. He nods knowingly: Today they are hiding something, and he has a fair idea what. He sings no more but concentrates on the glow on the inside of his eyelids.

The flashes of light rearrange to form a young man making love to a woman. Again, he can create no faces but can feel the frenzied breathing and hear the moans. Her body is supple and receptive and matches each thrust with equal passion. In time, the man rolls off, breathing heavily. The woman tries to pull him back and, finding him inert, tries to straddle him. But the man is completely spent. The lights become angryred and intense and contract to two circles that are headlights of a monster truck. The woman glances back toward the young man, then merges into the silhouette of the truck as it roars off. The man watches helplessly. Raimoti relives the man's perplexed agony.

His eyes, though still closed, smart with a forgotten pain, and everything blurs for a moment. And in that blur he thinks he sees another woman floating out of the shimmering haze. This time he cannot make out the size or shape of her body. She seems to be made of flames, and he feels the burn. He watches inwardly as the two figures dance a rhythmless dance from one corner of his eyes to another, fusing and slowly curling into ashes.

Nothing happens for a while, and then a black wooden doll emerges from the ashes and stares fixedly at him. Something stirs at its feet, and Raimoti is surprised to see the young man reappear from the ashes. He seems calm, almost detached. The doll slides toward him, but every time she comes close, the man takes a step away. At last the man halts outside the entrance of a cave, and the doll stops following. He takes a long, hard look at it and leaps into the gaping mouth of the cave.

Inside the gloomy cavern, the man is blinded. He gropes desperately and tries to find his way around the winding passages. He doesn't want to be there but is unable to find his way out. As he cannot see, he learns to follow sounds. Sometimes, when it is too quiet, he sings to dispel silence. Time passes, and he grows gnarled and bent, eventually taking to walking on all fours. His body becomes shaggy and heavy, and he loses his ability to sing. When he tries, it sounds more like a growl. His nails harden and lengthen into claws, and he moves silently through the cave, hunting rodents, snakes, and other small animals.

It is so dark now that Raimoti can barely discern the features of the strange creature that was once a sturdy young man. He tries to get closer to the dim form, but it hears him and lopes off. Raimoti gives a brisk chase, turns a corner, and stops. Ahead is a black lake, and the creature is hunched on the edge. He glares back at Raimoti and swiftly slips into the still waters. There are no ripples. Raimoti moves cautiously to the edge and peers down. He sees his own reflection leering at him. Suddenly, the level of the lake rises so rapidly that he leaps back. The cavern echoes with manic laughter, and a watery shape gushes out to lunge at him.

Raimoti screams and opens his eyes with a shudder. He is perspiring heavily from the play of lights inside his head. There is a very faint chuckle from somewhere deep in the tunnels, and his skin crawls. He looks down at his hands, shaking violently, and curses his wretched life.

He never wanted to be a miner. His father had been a prolific man, producing nine sons and five daughters with his two wives. Only three sons and four daughters survived to adulthood. In his carefree adolescence, Raimoti wanted to be a musician. He had a noble voice, a gift from the gods, and a fine ear for sound. He was always in great demand for Durga Puja and Ramlila. Once he had also traveled to the state capital for a performance. But everything changed when he lost three of his brothers within a span of two years. With many sisters of marriageable age, his family needed income. His younger brother died suddenly of cholera, just before his eighteenth birthday. So providence provided Raimoti's father a welcome opportunity to bring his wayward son back into the family profession. Raimoti was well above the average age when miners joined the company, so his father bribed the patwari to fudge the records and declare Raimoti the younger brother. The memories of his dead brother were buried beneath the immediacy of economic necessity. One fine day Raimoti wrapped his beat-up harmonium in a tattered sheet and picked up the shovel. And although he had lived another man's life all these years, he was determined to die his own death -- singing to his gods on a chaupal in front of his favorite temple. In the meantime, he hunted for the sound of water, a sound that his father had talked of but never heard; a sound that his grandfather had rambled about in delirium on his deathbed. A sound that spelled doom for a miner.

This morning, after his gang had donned their crumbling gum boots and helmets with torches, Raimoti had a strange foreboding. When they descended the shaft in the wobbly lift and started walking down the murky decline into the labyrinth, he heard the ghost of the Beast stalking them from the flanks. The Beast tiptoed, at times ahead of them, at times behind them, but always around them.

Raimoti feels drained and decides to go no farther. He is sure that he is very close, but he doesn't know where else to search. With heavy treads, he retraces his steps and reaches the place he started.

Raimoti can hear the faint laughter of his mates. He pauses to listen again. Still nothing. He is certain the Beast is lurking somewhere close: stealthy, restless, menacing. He places his hands against the moist walls of the tunnel, painted white with chalk dust as a precaution against accidental combustion of the surface. The rocks palpitate ever so softly, but there is no sound of the footfall of the Beast. As he turns back, he feels the rustle of a thousand fears behind his stooped shoulders. He retreats from the narrow gully into the main corridor, which leads to the mine face where his gang is waiting. He stops to take one last look before the walls squeeze him out to the relative brightness of the dimly lit corridor.

The five of them sit huddled against a small heap of coal that they have extracted. Three barrows have already been filled, and they will work till all six are brimming before they are permitted to return to the surface. Raimoti joins them and squats on his haunches. No one is permitted to smoke in the mine, so they share a slimy pouch of tobacco.

"What's the matter, kaka?" Arif asks with a twinkle in his eyes. "Are you hunting again?"

Everyone laughs. They know about Raimoti's eternal quest and find it amusing. Raimoti chews his tobacco in glum silence, spitting out a brownish stream of pik on the wall.

"Arre! The old man has the jitters again," comments Birsa, a sturdy lad from the hills, barely into his twentieth year. "I tell you, kaka, you worry too much, and it gets on our nerves at times. Where did you disappear to?"

"I heard some noises when we were coming down," Raimoti explains patiently, "and I thought I would investigate. I have been worried ever since the lake flooded last week. It is too close to this pit, and we have been digging toward it for the past month. You should be worried, too, beta."

"Why? Didn't we have an inspection by the engineers? They declared that the water wall is at least two hundred meters away. We will finish with this corridor by next week, and then they will probably close down the mine and shift us to the new one."

"Hatt re!" Arif says with disdain. "Those beti-chod sahibs will never let us leave till a couple of pillars or at least some scaffoldings collapse, breaking a few bones. The mader-chods are pitiless. But kaka, there really is no reason to fear. We are safe. I heard it from Ram Babu, the supervisor. He has opted for duty while we work this portion so he can take next week off for his daughter's wedding. He is such a coward that he never would have taken the risk if he felt there was the smallest danger."

Arif is the leader of the gang and tends to be abusive and aggressive. He was working in the latest mine, Number 8, when he fell into an argument with a junior engineer and smashed a shovel over the other man's head.

"You tried to break the engineer's head!" the inquiry officer charged.

"No," Arif replied, "I was only trying to break the motherfucker's teeth. His head got in my way."

Subsequently, Arif also fought with the union representatives who tried to intervene and wrangle some concessions out of the management on the pretext of settling the dispute. Arif called them whores and refused to get involved in their politics. He was promptly shunted to Mine Number 3 to rot. He has known Raimoti for many years and had been among the first to rush to extract the body of Raimoti's son when he was crushed to death in a minor collapse of the mine ceiling. Since that day Arif, himself an orphan, has loosely adopted Raimoti as a father. This prevents the other youngsters from taking too much liberty with the aging miner. The two also share a love for music and spend hours listening to songs, quawwalis and bhajans, on Arif 's tiny cassette player when Raimoti is sober and not under influence of the locally produced hadia or ganja. Arif, a religious man, doesn't consume these shaitani poisons. His only weakness is women. He is famed to have slept with every known whore in the vicinity and with some unknown ones besides.

"The only thing I do well is dig," Arif is fond of bragging. "With my pickax and with my prick!"

Raimoti is quite fond of Arif and thinks of him almost as a son. Like his father, Raimoti was a productive man and had six children before Mahila Jagaran Morcha -- the local women's empowerment group -- enlightened his perpetually pregnant wife and she forced him to have a vasectomy. He received an additional increment in recognition of this sacrifice, as per the company's policy. The government wanted its workers to produce more coal, not children. Soon thereafter, his younger son died of tuberculosis, and his older son died in the accident a few years later. His daughters fared better and were alive, to the best of his knowledge, though unhappily married to loaders and miners in other coalfields. He was hardly in touch with them. His wife, Dulari, a comely lady, abandoned him long before for a truck driver, leaving him to look after the children and get them married or cremated, as the situation demanded. Raimoti now lives with his only surviving brother, Madho, the youngest, and Madho's wife and three children. He gives half of whatever he earns to his brother, keeping aside the rest for his addictions and stray personal expenses.

Arif looks at his watch and gets up to stretch. He kisses the pickax and saunters toward the coal face. This is a sign for the others to end their rest. Raimoti, being the oldest and the weakest, is handed the shovel with which he has to keep loading the barrows.

Arif urinates against the exposed boulders of coal, shouting, "Look, kaka, I piss into the arsehole of the earth! Now it is plugged from this side -- nothing can pass through. You are safe, all you beti-chods! Dig away!"

They begin pounding the rock face in a steady rhythm...dha-tun-na! Dha-tun-na! Dha-tun-na!

They are transported from the reality of the world outside -- its sights, its smells, and its sounds. Nothing else reaches in here, where the earth lies tiredly exposed, split open to the manic pummeling of man in his lust for riches. For centuries the earth has been ravaged, gnawed, and bitten, yet she lies there, uncaring, unresponsive. How long? Raimoti wonders. How long will she take it before she decides it is enough? How long before she crushes the perpetrators in one gigantic twitch of her loins? How long before the Beast, nestling within her, emerges to swallow these plunderers? Not long, the whispers echo behind him, pricking his scalp, making him break into a cold sweat. He turns around to find only the receding vision of the tunnel before it bends out of sight. The bats of fear fly twittering away from him into the crisscrossed web of abandoned gullies. They hear the Beast!

"What was that?" Raimoti screams, throwing down his shovel. His eyes wide open, his mouth dry, he listens intently for the footfall. Thump! It comes, only a wraith -- unclear, unformed. Haa-haa-humph! it chortles, a little louder.

"What is it, kaka?" Arif asks, putting down the pickax.

"I heard it! It's on the other side of that face!"

"What? Are you drunk, kaka? Or has coal filled your senile brain? What do you hear?"

"Hushsh! Listen." The gang is shaken and they strive to listen. No one breathes. The only sound

they hear is their own heartbeats, thumping nervously like a tambourine within their heaving chests. The stillness is absolute. The silence complete. After an interminable moment they hear a sound. Faint but true: chchapp! gglugg! Like a little bubble bursting to the surface. Then silence again. Nothing. They wait, but still there is nothing.

"Chalo, bahin-chodon! Work," Arif says finally. "It's nothing. This crazy old man will frighten us to death. It was probably his empty stomach revolting against all that hadia he had before coming down. Do us a favor, kaka. Go and crap somewhere so we don't have to suffer your bowel sounds again."

Raimoti stands still. He can't be mistaken. He has dreamed of it too often. His father and his grandfather described it too well. "At first it will sound like a massive bubble," they said. "Then there will be creaking, as of a cot under a fat woman. Then there will be rumbles, followed by a deafening crash. Then you will die."

There is a dry creak from behind the wall in front of the gang. Arif hesitates a moment, then shrugs. He lifts the pickax in his burnt-brown and sinewy arms and swings it down with all his might.

A small chunk of coal falls off, no bigger than a man's head. Then they notice the trickle. At first it is just a slick, quite common in the underground. But soon it grows into a thin jet of icy water -- almost like the stream of urine Arif spouted.

It's the first claw of the Beast.

They hear an ominous rumble from within. Copyright © 2009 by Sanjay Bahadur