Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

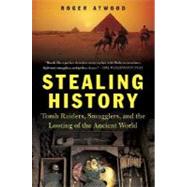

Looking to rent a book? Rent Stealing History Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World [ISBN: 9780312324070] for the semester, quarter, and short term or search our site for other textbooks by Atwood, Roger. Renting a textbook can save you up to 90% from the cost of buying.

| Introduction: Looters in the Temple | 1 | (18) | |||

|

|||||

|

19 | (14) | |||

|

33 | (27) | |||

|

60 | (17) | |||

|

77 | (9) | |||

|

86 | (23) | |||

|

109 | (14) | |||

|

123 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

131 | (36) | |||

|

167 | (9) | |||

|

176 | (12) | |||

|

188 | (22) | |||

|

210 | (19) | |||

|

|||||

|

229 | (12) | |||

|

241 | (9) | |||

|

250 | (13) | |||

| Epilogue | 263 | (8) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 271 | (4) | |||

| Notes | 275 | (36) | |||

| Glossary | 311 | (4) | |||

| Select Bibliography | 315 | (8) | |||

| Index | 323 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.