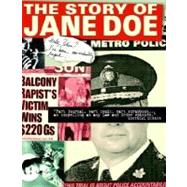

| The background A preliminary note from Jane Civil trial journal | |

| Safe at home in bed | |

| ""First interrogation"" (in the voice of Bill Cameron) | |

| Ruined blue party dress | |

| ""She's not such a tough nut"" (in the voice of Bill Cameron) | |

| ""Our own worst nightmares"" (in the voice of Margo Pulford) | |

| What's a Gentleman Rapist? | |

| ""Goddamn, if she didn't poster"" (in the voice of Bill Cameron) | |

| ""She's not the enemy"" (in the voice of Margo Pulford) | |

| Eating grass with the police | |

| ""They tell me not to call he | |

| Table of Contents provided by Publisher. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Excerpted from The Story of Jane Doe: A Book about Rape by Jane Doe

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.