What is included with this book?

CONTENTS

Overtures

FATHERS

The Landings

The Collector

Root-Light

Flight School

The Color of Rust

All Saints

SONS

The Two-Car Garage

Serpents

Bring Home the Coke

Loners

God's Script

Moonshine

RIVALS

Positano

Barnstorming

The Night Pool

The Corvette

Apollo

At the River

The Cutting Room

Resting Place

ENEMIES

The Canoe Beneath the Hammock

Re-enactment

Women

The Sudanese Dagger

The Sea and Old Men

FATHER AND SON

Vectoring

The Nightmare Life in Death

Walls of Books

Closings

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Index

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The plot was simple and strong: Four Southern suburbanites decide to go canoeing in the last remnants of the Appalachian wilderness. They are Lewis Medlock, a survivalist determined to master Nature single-handed; Ed Gentry, a friend whose only real acquaintance with the wild is what he sees reflected in Lewis's fierce excitement; Bobby Trippe, a soft denizen of sales meetings and country clubs who's just along for the ride; and Drew Ballinger, the conscientious family man who, like the rest, has no idea at all what he's getting into. These four plunge into a wilderness populated by few and brutal

inhabitants -- a terrifying place where one of them is sodomized at

gunpoint, one is killed, one almost loses a leg, and all of them learn,

of necessity, to murder.

I'd been watching that plot, the book, the script take shape since the days when my father took me onto the mild rapids of the Chattahoochee in an aluminum canoe, when I was hardly big enough to see over the gunwales. I'd never forgotten that night he and Al and Lewis King came back from the Coosawattee hurt and scared. I'd seen the arrow tremble on its rest as the tension of the bowstring grew too much to bear, and the silent flight of deer over fences as we staked out frozen cornfields; seen the young men climbing cliffs above the Italian sea, seen the narrow-eyed sheriff send us on our way at the edge of the Painted Desert. My father had sat in our living room in Atlanta in the fall of 1962 and talked the plot into that first Grundig tape recorder we'd bought in Germany, and we had all felt the fear of the wild among the dense, dark forests of Oregon. And all the while that he'd been writing the book, he'd been thinking of what the movie might be.

The novel hit the stands in the late spring of 1970 and climbed the best-seller lists quickly. Only the phenomenal success of Erich Segal'sLove StorykeptDeliveranceout of the number-one position. I watched from a distance. Jim Dickey was really on a roll, and all I could do was stand aside, amazed and amused, proud and a little appalled, as he loomed larger and larger in the book reviews, the magazine articles, on talk shows and publicity tours; combative and funny, drunk and outrageous and ruthless, in fact -- and even more outrageous and ruthless in the stories he told about his experiences. Talk and testosterone were taking over, with heavy hits of Jack Daniel's to keep things going. At a book-and-author luncheon with Erich Segal and Pauline Kael, Segal told the little old ladies that in his novel the only four-letter word was L-O-V-E. When the luncheon was over, and the three of them had crowded into the back of a limousine, somebody turned to Segal -- my father would sometimes attribute this remark to Kael -- and said: "Listen, you little cocksucker, what do you know about L-O-V-E?" It was a story that Jim Dickey liked to repeat on any and all occasions.

When I talked to Columbia on the phone, I would tell my mother what I was doing, and my father would tell me what he was doing. But his tales, exciting as they were, didn't lure me home the way they had before.

I was happy now not to be there. I had my own family to tend to in Charlottesville. We'd bought a big dog and rented a little house in the country. On warm days we swam in our own lake; when it was cold we had our own fireplace. I got a four-wheel-drive Ford Bronco and gave the Jaguar back to Big Jim. I went to my own classes and wrote short stories and started seriously to take photographs and study film, trying to cobble together my own primitive little documentaries. I liked the distance from my father. It made it so much easier for me, in my way, to try to be him.

Jim Dickey was only beginning to learn how little he'd have to say about the way his book was made into his movie. But he would always talk about whoourdirector was going to be, and our stars. To play the role of Ed, who narrates the book, Jim Dickey wanted Gene Hackman. But Hackman wanted to play Lewis. Or so it was said. To direct, Dickey liked Sam Peckinpah, who made his mark on Hollywood with the relentless violence, horribly literal and beautifully stylized, ofThe Wild Bunch.Peckinpah, an ex-Marine who specialized in Westerns, had a feel for the society of dangerous men in dangerous situations. His "misogynist heroes experience passion only in slaughter," said a British critic. Well, you could find worse sensibilities for the story at hand.

They met in London, my father remembered when all of this was coming back to us from the distant past. "We talked almost the whole day long, Peckinpah and I, and I really thought he was going to be good. He had everything down in his head just like he wanted it." My father smiled beneath the oxygen tube. "We were talking about certain scenes and he said, 'You know, Mr. Dickey,' he says, 'I am famous for what they call my blood ballet.'" And now my old, sick father erupted with laughter. "I said, 'Well, we've got plenty of room for that in this movie.'"

Peckinpah said that what the two men had in common, and not just because it was the end of a long hard-drinking day, was their desire -- Dickey in his poetry, Peckinpah in his films -- "to create images people cannot forget." My father thought that was so right that more than a quarter-century later he could even remember where and when Peckinpah said it, in the late afternoon standing there on Regent's Street saying goodbye. "I never did see him again."

The director, in the end, was John Boorman, who was British and had done two action films with Lee Marvin:Point BlankandHell in the Pacific.The last film Boorman had done was an embarrassing romp with Marcello Mastroianni calledLeo the Last.No one we knew had ever heard of it. But the studio liked Boorman, and Jim Dickey learned to live with him, and said he thought he was great, at least for a while.

The making of the movie brought me back to my father of course. How could it not? Movies, remembered or imagined, had become our last common language. This, at last, was the real thing. None of us wanted to miss it.

It was May of 1971 when Hollywood moved to the little town of Clayton, Georgia. My father, my mother, her mother, my twelve-year-old brother, myself, my wife, and my child all followed. In a Toyota Land Cruiser, which was my father's second car (along with the XKE), a Cadillac Sedan de Ville he'd bought for my mother, and my Ford Bronco we left that suburban house in Columbia and headed up into the hills, across the Chattooga River. My father took with him his bows, arrows, guitars, and tape-recorded music to show Boorman just what he wanted. We were headed into the mountains ofDeliverancethinking we were pioneers, but thinking, too, that we already knew our way around. This was coon-on-a-log and corn-liquor country. Grandpapa's stomping grounds. Wha-cha-know Joe's neck of the woods. "The country of the nine-fingered people," as it says inDeliverance,because there's so much inbreeding and so many bad accidents that everybody's missing something. This was a place we knew about, and knew enough to fear -- but it was ours. The British director, these Hollywood crews, they wouldn't have much of a feel for North Georgia. But we Dickeys were ready for the backwoods boardinghouse where the toilet would be down the hall, if we were lucky, and the screen doors wouldn't quite keep out the mosquitoes.

When we got there, we were put up in A-frame chalets around the golf course of the Kingwood Country Club. Clayton, it turned out, was a burgeoning resort area, an outpost of Atlanta. Within the confines of the club, at least, Hollywood was right at home. And we were no longer sure what to expect.

The evening the Dickeys arrived, Boorman gave a party for the author, to introduce him to the cast and crew. Boorman's German wife, Christel, was with him, and his four blond children. The whole scene was supposed to feel "like family." But things had started to get a little sullen and ugly already in the afternoon. My father had been handed the shooting script that he thought he'd approved. But this one started with a terse note: "Scenes 1-19 omit." This was going to be an action movie that began and ended on the river. Real clean. Real simple. Really not what my father had in mind.

On the way over to Boorman's $1,000-a-month cottage, we had to squeeze the Cadillac by a big car headed out the drive. Burt Reynolds was at the wheel, his shirt a little too small so it showed off his biceps, a wide-brimmed Stetson on his head. It was the first time we'd seen him. "Afternoon, ma'am," he said, doffing the hat, and then he drove on. He was going to be Lewis.

Boorman greeted us at the door of the house. My father had been working with him for months, but I'd never seen him before. Long hair, gapped teeth, ruddy complexion, a British accent and manner that had nothing to do with this place or this story. He was going to be a spectator here, I thought. He didn't know these people. But, then, I wasn't sure any more that we knew them either.

Jim Dickey stalked into Boorman's living room like he would have done when he was creeping up on a bear in West Virginia. Or as if he were the bear. I'd forget sometimes what a big man he was, what a huge presence, but when he'd been drinking, as of course he had this night, he lumbered dangerously through the fragile auras of strangers in small spaces. Boorman followed behind him to make introductions -- and to watch. Dickey was introduced to Ronny Cox, who'd play Drew. Tall but ineffectual, his hair bleached blond at the time, Cox resembled Rod McKuen, whose book of sentimental verse,Listen to the Warm,was a best-seller. This did not enhance his image in my father's eyes. Jon Voight came to the party a little later. He still wore the

credulous look of Joe Buck, the baby-faced gigolo inMidnight Cowboy.He was beginning to grow a mustache to give his features a little maturity, but he seemed way too young to play Ed. Someone told him, "Dickey has arrived." He fixed himself a drink from the bar near the door. Would he like to meet Dickey now? Voight stood up to his full height, took a deep breath. "I guess now's as good a time as any," he said, and into the living room he went. He'd heard tales about the way Dickey came on, the way Dickey could get to you.

After a while my father worked Cox and Voight over to a table by themselves. He was uncomfortable with most of the others at the party: moneymen, secretaries. They were Hollywood's version of gray affable men. They were Boorman's people. It was the actors my father wanted to talk to -- to perform for -- and so he did.

"Do you really want to play Drew?" Dickey asked Cox.

Boorman listened from across the room.

Cox looked scared, but managed to say finally, with overintense sincerity, "I really do."

Dickey paused for effect, let the anxiety linger for a second, then slapped Cox's knee and smiled. "Good," he said, "because I want you to."

Cox and Voight grinned. Boorman let out his breath.

For the next few days the actors were rehearsing, waiting for Ned Beatty to arrive. The crew was getting used to working in the mountains and on the river, running tests, sorting out equipment. Cox and Beatty were theater guys, not movie people. But Beatty's reputation impressed everyone. He was late coming to Clayton because he was finishing the run of a new play by Eugène Ionesco. He was serious; or supposed to be. But the first time I met him he was wading around in his tennis shoes and pants, fat, playful, childish, and funny. "I like to get my feet wet," he said with a well-honed grin.

Boorman would invite small groups of people over to his house in the evening to play Ping-Pong and have drinks. Boorman was trying to build that sense of informal family, full of confidence, where people trust their emotions and reveal their secrets, and where he was the only man who understood it all and made it work. But as long as Big Jim Dickey was there, nobody was going to believe that.

After a few days my mother, her mother, and my brother left. But my father stayed. He said he thought he was needed for the music -- he'd heard that song called "Dueling Banjos" at a folk concert in Portland seven or eight years before and he'd brought the tape and he could pick it himself for anyone who wanted to hear. He wanted it as the theme. Forhismovie. And it was so right, in fact, that Boorman took the idea. Then Dickey stayed for the actors, he said. Boorman was still rehearsing them in semisecrecy, but they were coming on the sly to see Dickey for background on the characters, even voice coaching. Voight recorded hours of Dickey accent.

I was slated to stay on as a stand-in, a warm body around whom lights and camera angles are positioned so the actors will be able to come on fresh for the actual shooting. It's about as lowly a position as you can get on the set. But you're on the set. You see what goes on. You learn. And I was taking notes the whole time. Later, my father told interviewers he worked on the movie himself partly because he wanted me to get that job. It was the kind of thing that he'd say that always left me uneasy. There was no question he'd gotten me the job. But there was no question he was anxious to work on his movie whether I was there or not. "We need to have a very long script conference, I need to see the locations and a lot of other things," he wrote in his journal a couple of days before we drove up. "It is going to be an awfully hard-working summer, but I am really ready for it, and will not give down. It is going to be one hell of a film."

My father, my wife, my little boy, and I were settling in for the long haul when Boorman asked Dickey to lunch at the Kingwood Club. In the late afternoon my father was back, knocking on the door of my room. Our year-old son, Tucky, was napping. We were watching soap operas.

"I'm leaving," my father said, as if his world had crumbled. Boorman had said he was interfering too much. Said the actors were upset by his presence. Boorman had said, "Jim, if you want to direct this picture, fine." Dickey had said of course not, John was the director; John was theauteur.And John had said in that case he thought it would be best if Jim left.

Dickey took a long sigh and shook his head. "So -- I guess I'll be going sometime this evening."

"I think it was largely Burt," my father said when we were going over this ancient history one day in Columbia. I thought that by looking back on that summer I could distract him from his sickness, and I thought that I would find more clues about us.

"You think it was Burt?"

"Yeah. Do you remember that publicist up there? He gave me to understand that I made Burt nervous."

I think my father made everybody nervous in the end. Cox, Beatty, Voight, and Boorman, too. Especially Boorman. But it was true that Burt seemed the most fragile. The making ofDeliverancewas a big break for everybody connected with it. It meant more money, more work, more fame. But Burt was looking for respect. He wasn't coming from the stage, like Ronny or Ned, or from an Academy Award-winning film like Jon. He was coming from one ludicrous television series after another, most recently an uninspired detective show calledDan August.Ned and Jon were accomplished actors, but Burt was a former stuntman who wanted to be a star. He was made by and for the screen. The question was whether he could make it from the little one to the big one.

Burt was sharp, funny, self-deprecating, taking shots at himself before others could get them in. But he was excruciatingly sensitive about his height, supplemented by lifts in his boots, and his hair, which was disappearing fast. And if he was going to make it in this movie he was going to have to act. He was going to have to concentrate. He was going to have to feel just about as sure of himself as he ever had in his life. And Burt sure as hell didn't need Jim Dickey, who really was big, who'd played a little football, too, who could be the redneck in the morning and the intellectual in the afternoon -- who was half Lewis Medlock himself -- to tell him anything, anything at all.

"I just couldn't handle his act -- his Jim Bowie knife on his belt, cowboy hat, and fringed jacket," Burt wrote in his autobiography.

"The contacts I had with him were amiable enough," my father said, a little wistful, disappointed, and angry even all these years later. "We rode back from one of the locations together a long, long ways out, and he and I talked for a while. And it seemed all right to me. I don't know anybody else's version."

I was left alone in Clayton. The Dickey. And Boorman probably would have gotten me off the set, too, if it had been worth the trouble. I wasn't quite right as a stand-in: too short to be Jon or Ronny, both of whom were over six feet; too skinny to be Ned. I was the right height to stand in for Burt, but Burt, playing the star game, had to have his own personal stand-in. So I just went wherever I was needed whenever I was needed, walking through the moves of one actor or another, especially the rednecks. I kept a low profile. I knew how to do that. I was nineteen years old and wasn't going to intimidate anybody. Keeping me around was an easy concession.

Boorman simply stopped paying for my accommodations. When Jim Dickey left, none of the Dickeys had a room at Kingwood any more. I didn't have the money to pay my own bill staying with the stars, or even at the Heart of Rabun Motel, where most of the blue-collar crew were housed. So we found a little bungalow in a local low-rent motel and moved out of Hollywood onto a kind of borderland between movie fantasy and redneck reality. And I liked it. More and more of the friends we made were local hires: trailer-park girls who worked as waitresses; good ol' boys who thought they'd had a fun night if they saw a knifing at a roadhouse. My old Southern accent -- lost long ago, when we moved to Oregon -- started to come back. I started to feel, at last, like I did have a claim on this place.

Warner Bros. got some of its extras that summer out of local jails. One was released into the producer's custody every morning and went back to bed behind bars every night. A lot of them had never seen a job that paid so well. "I found out a long time ago I could make more money raisin' children than raisin' hogs," as one of the older ones liked to say. But even by mountain standards the work could get boring. "Ain't had so much fun since I cut my toenails," you'd hear them say. When those first scenes were being shot, there was plenty of time to sit back, chew on a blade of grass, and talk.

One of the locals I liked a lot was a reputed moonshiner named Randall Deal. He swore up and down he'd reformed his ways. Problem was, the police just wouldn't believe him. Randall was built solid, with heavy arms and a barrel chest, and a look in his eye about as mean as you could find in those mountains. In the movie he plays one of the Griner brothers, paid to drive the suburbanites' cars down to Aintry, where they're supposed to pick them up when they get off the river. But it's clear the Griners don't think much of these city boys who seem to have trouble even finding the water. "It ain't nothin' but the biggest fucking river in the state," Randall says in the film, and you do get the feeling he'd kill you as soon as look at you.

"How come you was in jail?" I asked him one day as we were lying around in the sun near some of the shacks the prop people built.

"Well, it was like this," says Randall. "I wadn't doin' nothin'."

"Unh-hunh." I wasn't sure how far I wanted to push this, but I got my question out. "How come they arrested you, then?"

Deal looked at me like I'd just missed the biggest fuckin' river in the state. Why, he was just driving his car minding his own business when a state trooper pulled him over for no reason at all. "I wadn't doin' nothin'."

"Unh-hunh," I said again.

"And this trooper, he commenced to beatin' on me with his stick. I just sat there and he kept beatin' and beatin'."

"But I heard you was in jail for assaulting a..."

"Well, finally I just had to get out of the car and unconscious him."

"Unconscious him?"

Randall just smiled.

Other mountain people used in the movie weren't so tough, and in fact they were terribly vulnerable. The face that you don't forget when you seeDeliverancebelonged to a backward boy of fifteen named Billy Redden, who had the role of a retarded banjo player. His thin-lidded eyes and simple grin are haunting on film, and they were just as disturbing to see on the set. Billy seemed so lost. He went around bumming cigarettes, proud of himself for smoking in public, more interested in his Marlboros than almost anything else that was going on. And he did try to do as he was told, but some things were beyond him.

The movie opens with a sequence at a backwoods gas station, where Drew on the guitar and this boy with his banjo start out just sort of picking a few notes, then take off into a burst of bluegrass virtuosity: "Dueling Banjos." Nobody ever expected that Billy could play that piece, or any piece. The music was all going to be dubbed. But Billy couldn't even fake it. He could make his right hand strum more or less convincingly, but he couldn't imitate the fretwork with his left hand at all. In the end the scene was set up with Billy sitting on a kind of swinging bench, and another little boy hidden beneath it, whose left hand up Billy's sleeve was faking the fingerwork for the camera.

In that same sequence, Ed looks through the window of a little shack and sees an old woman whose face is covered with skin cancers tending a spastic child whose head lolls pitifully to one side. The little girl was thirteen, but you would have thought she was five or six. Of course Hollywood paid these people and treated them as gently as it knew how to do, but it was hard to get over the feeling as the lights went on and the cameras rolled that souls were being stolen here.

Copyright © 1998 by Christopher Dickey

From "The Cutting Room"

Most movies are shot in what seems a random order, and the various scenes are assembled later into a whole. ButDeliverancewas filmed in sequence. Each day moved the cast and crew a few more pages into the story, farther along the river, deeper into the woods. All the horrors were foretold.

At the beginning, because we knew what would come later, simple accidents somehow felt like omens. The first day on the Chattooga River, the camera crew and actors set out early in the morning in a flotilla of rafts and canoes. They barely made it a mile downstream. They broke one of the canoes in half. They ripped the bottom out of a raft and spilled thousands of dollars' worth of camera-and-sound equipment into the water. No one was hurt, but everyone was soaked, tired, worried, and maybe a little scared. The characters in the story had gotten too far into these woods, too deep into this river. The fact was, you didn't know what might happen up here.

On that first day of the story, the four men run a few mild rapids, then set up camp in the late afternoon. Lewis, played by Burt Reynolds, goes out in a canoe to see if he can shoot a trout with an arrow. Ed, along for the ride, lies back and has a beer. They talk about their lives. Lewis talks about how civilization is going to fail. He takes a shot at a trout and misses. Ed says he doesn't think his own life is as shitty as all that. Helikeshis life. Lewis takes another shot and skewers the trout that they'll eat for dinner.

Since I was James Dickey's son and I was supposed to know how to shoot a bow, one of the assistant directors asked me to shoot one of the trout they'd put in a little makeshift pond at the edge of the river. They needed a close-up miss and a close-up hit. I'd never shot a trout. But, hey, this was going to be like -- thiswas-- shooting fish in a barrel. Just to get the feel of it, I took aim at one of the trout, steadied the shaft, aiming low to compensate for the refraction of light, and released. The arrow went right into it, just the way it was supposed to. Now the cameras rolled. And rolled. And rolled...and rolled. I could not hit another fish. We joked. We laughed a lot. I made excuses. The sun was going down and we were losing light. This whole little sideshow was turning into an embarrassment, then a humiliation, as people came over to see why we were taking so long. "I thought you knew how to do this?" said the assistant cameraman. Even fish in a barrel are hard to hit with an arrow. Anyone might have made an equal fool of himself. But I was Jim Dickey's son, and I wasn't able to do what he could do -- or, more precisely, what the characters he created could do. The arrow splashed into the clear water another time. Now the trout wriggled in agony. Finally. Good enough. I should never have said I'd do this, I thought. I was Jim Dickey's son. Yeah. But I was only his son.

At the end of the first day in the story, there is a long scene by the campfire, where the men, now drunk, let themselves get spooked by the sounds of the forest. In the book, Ed hears something hit the top of the tent. "The material was humming like a sail....The cloth was trembling in a huge grasp." He shines a flashlight directly above his head and sees "a long curving of claws that turned on themselves." The owl -- a very big one -- flies away, then comes back. "From some deep place, I heard the woods beating." It perches again above Ed's face and he reaches up slowly, gently, until he can touch the claw, feet it tighten, feel the strength that "had something nervous and tentative about it." I always thought it was a wonderful scene, and it meant something special to my father, and to me. This was the owl from our tent by the lake; and the Owl King of his poetry, the symbol of fathers, the teacher of the blind child. "All night the owl kept coming back to hunt from the top of the tent....I imagined what he was doing while he was gone, floating through the trees, seeing everything. I hunted with him as well as I could, there in my weightlessness. The woods burned in my head. Toward morning I could reach up and touch the claw without turning on the light." But in the movie there is no owl. Nobody would know what it meant. The imagery wouldn't work in Boorman's spare film. There is just the dark, the four men, and their fear.

The next morning, Ed wakes early. He's got nothing on but his long underwear as he takes his bow into the woods, thinking maybe he'll get himself a deer. And he does see one, a little spike buck just visible through the mist. "The ghost of a deer, but a deer just the same." He draws down on it, steadying the arrow, trying to steady himself. But at the moment of release, he loses control. The deer turns and runs. The chance is lost.

To shoot that scene, a little deer was brought in from an animal park, and heavily tranquilized so it could be easily controlled. There was never any question of shooting it, or hurting it in any way. But it died. It had been given an overdose. Boorman and his assistants were in a quiet panic. "This is all we need," I remember one of them saying. "The fucking SPCA will crucify us." So the death of the deer was treated as a terrible secret, and those of us who knew about it were admonished to say nothing to anyone. And we didn't. But the death of this little animal, like the exploitation of that tiny thirteen-year-old girl, so vulnerable, so lost in the machine, filled me with doubts about everything we were doing.

Copyright © 1998 by Christopher Dickey

"Resting Place"

Warner Bros. had built a dirt road to a dark laurel thicket by the river. It was a rough, steep track that got slicker and more dangerous every afternoon, when rain poured from the skies. The trees were enormous, forming a thick canopy hundreds of feet in the air. It was a rain forest, right here in the mountains of Georgia. Its floor was so shadowed that small plants found it impossible to grow in the thick loam of the rotting leaves. The mountain laurel was not shrubbery but a collection of trees twisted like gnarled fingers reaching for the light. The whole effect was beautiful and threatening. This was where the rape scene was going to be filmed. The script called it "Resting Place."

It is the second day of the story. Ed and Bobby in one canoe have gotten separated from Lewis and Drew in the other, and they pull over to the side of the river to wait for the others to catch up. Coming at them out of this dark forest they see two mountain men, one of them carrying a double-barreled shotgun.

One of the mountain men, the smarter of the two, was played by Bill McKinney, a serious character actor whose main obsession off the set seemed to be looking after his body. Each morning he swallowed dozens of vitamin and mineral pills, and when he talked to you he'd study with casual fascination the veins and sinews standing out on his own forearms. Burt claimed he saw Bill running naked through the Kingwood golf course in the early mornings.

The other was Herbert "Cowboy" Coward, who had worked with Burt a few years before at one of those Wild West shoot-out shows in a rickety amusement park in the Smoky Mountains. Cowboy was no actor, but the script called for the character to be missing his front teeth, and Cowboy looked like his had been knocked out with a ball-peen hammer. The character had to seem at once terribly stupid and terribly frightening, Cowboy could do that. He never left character. But when he talked, he usually stuttered, and when he tried not to stutter, words would come out in weird orders. "You ain't a'goin any damn wheres" was a line that stayed in the movie. "I'm g-g-gonna lay a b-b-big long dick right in your mouth" was one that didn't.

For the first few days at Resting Place, a full crew was on the set. There were some problems with new lights that the cinematographer brought in. The preparations were slow, conditions uncomfortable. A lot of people were getting sick in the constant damp and the changing temperatures. A couple of the gaffers who'd been working in the water day after day were getting lesions like jungle rot. Others were busy spreading calamine lotion on poison ivy, chigger infestations, mosquito bites. At first there were a lot of jokes about snakes, but there were a lot around, and soon they were taken seriously. We'd see cottonmouths in the water and big rattlers sunning themselves on the higher, drier stretches of the road. One day, as I was walking with the hair stylist from the set to the riverside mess tent for lunch, talking about the tensions that were growing around the scene that was coming, and not really thinking about where we were putting our feet, I saw a shape in the middle of the path just in front of us. It was fatally still. Its back was patterned like leaves. "Freeze," I said, and touched the hair stylist's shoulder. Her foot stopped in midair, inches above the copperhead. The snake's sullen, slow-moving skull lay like an arrowhead in the black compost, its body thick and passive. One of the lighting men decapitated it with a shovel and skinned it. We knew there were others around, waiting.

The stars rehearsed, memorized lines, or practiced canoeing. All of them were getting pretty good at it, and out on the river, most of the day anyway, at least there was sun. But at Resting Place the mood was getting darker. Ned Beatty no longer played the happy fat boy around the set. He was getting harder to talk to, brooding, concentrating.

The day of the shooting, Burt and Ronny weren't called. The press, even the studio's photographer, was barred from the set. Donoene the hair stylist and Cindy the nurse were asked to go watch the river.

There is a full rehearsal that tells us what's to come. One of Boorman's great talents is the way he orchestrates the movement of his actors through the frame, and the movement of the camera around his actors. His cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, sets up a master shot in which the actors go through the entire scene, and the camera takes it all in. Ed is pushed up against a tree and strapped there by the neck with his own web belt. McKinney takes a big hunting knife Ed carries and asks him how he'd like his balls cut off, then cuts a line across Ed's chest just to watch him bleed. Bobby is standing at a distance. McKinney tells him to drop his pants. Cowboy points the shotgun at him and gives a big grin that is no less horrifying for being so ludicrous, so hungry. When he's stripped to his jockey shorts, Bobby panics and tries to run. McKinney chases him; Bobby is trying to scramble up a steep hillside on all fours, but the earth and leaves slip away beneath him. McKinney grabs him, pushes him up the bank for a few feet, then follows him, pawing him, squeezing Bobby's ass and his breasts, sliding and falling back down into the rotting leaves. He grabs Bobby by the ear and the nose like a pig and half drags him, half rides him to a decaying log, forces him to lie over it, and rapes him.

One of the assistant directors called me from the sidelines and had me follow the actors through the scene. I was going to stand in for Ned while they set up the lights and the track for the camera. I didn't have to take off my clothes. All I had to do was go through the general motions, standing on the marks set up during the rehearsal, crawling as if in slow motion up the steep bank covered with leaves. No one led me by the nose, or rode me like a sow. But I had to lie down over the log, with the wood pressing into my stomach, and there were no jokes that could be made, there was nothing for anyone to say, that could keep me from feeling humiliated. I couldn't wait for this day to be over. But it was only beginning.

Jon and Ned, McKinney and Cowboy come back onto the set. They've been looking for a way to match dialogue to action, and somebody has the idea of making Ned squeal as McKinney forces him over the log. "Squeal like a pig....Squeeeeal!...Squeeeeal!" And Ned does, in terror at first, and then, slowly, horribly, the squeals become groans of pain. And finally Boorman calls, "Cut." Then the action is run again, and again, each time growing more grotesque.

At lunch there were several nervous, risqué jokes. There was some kidding about McKinney's getting carried away. Ned tried to snap back out of character, to relax. But it wasn't working. And that day, and for the rest of the time he was in North Georgia, he seemed to have changed, as if whatever sadness or insecurity he'd covered up before as a man, as Ned Beatty, just couldn't be contained any more.

In the afternoon there were more shots of the same scene, but now from different angles. I wanted to go somewhere else, but I had to stay available to stand in, or lie down, or kneel for every new camera setup. I didn't watch the shooting any more, but I couldn't get away from the sound.

That night I called my father. I was sick of the film, sick of the whole story. And I wondered why the hell he had to have this homosexual rape. "I had to put the moral weight of murder on the suburbanites," was what my father told me. It was what he always said. He had to portray the mountain men as such monsters that the suburbanites would decide not only to kill, but to try to cover up their crime. Lewis can shoot McKinney in the back with an arrow, and look around at this forest about to be inundated by a dam, and say, "Law? What law?" and every man watching will think, Yeah, bury the son of a bitch.

I understood that was the way it was supposed to work. But I didn't think my father understood what had happened that day filming by the river. In the book you can read the rape scene and know it happened, but you get around it and go on, and get other things out of the novel. In the movie -- it was becoming what the movie was about, it was the thing everybody was going to remember. "Squeal like a pig!" Not Lewis's survivalism, not the climb up the cliff, not Ed's conquest of his own fear. It was all going to be about butt-fucking.

"You're wrong, son," my father said.

There was something else that I wanted to tell my father on the phone, but I couldn't bring myself to say it. We were starting to hear from our trailer-park friends that there were a lot of people in these mountains who didn't like this film we were making. And you didn't know who might get it into his head to teach some of these movie people a lesson. There were plenty of real mountain men out there, with real guns. The director and the stars were all secure up at Kingwood; the rest of the crew were together at the Heart of Rabun. But I was here at this bungalow motel with my little family. We were all alone. And I was the son of the man who wrote the book.

I was scared. Scared enough to leave. But I stayed, because more than anything else I was afraid to admit how scared I was.

Each morning we struggled and slid down to some part of the Chattooga, and each evening we crawled back to Clayton. But the lingering depression that started in Resting Place grew worse. The work was no longer new. People had gotten to know each other too well. Even the river seemed to have run out of surprises.

Then we changed rivers.

On the mythical Cahulawassee there is a deep gorge not far downstream from Resting Place. The four suburbanites bury McKinney and head back out on the water with no idea what lies up ahead. The sound of the rapids is rising in their ears when Drew, in the lead canoe, looks like he's been hit by something. Without any warning he tumbles over the side. Now they are all caught up in a rush of white water too powerful for any of them to handle. One of the canoes is broken in half. The other tumbles through the falls. By the time they reach still water at the bottom of the gorge, Lewis's leg is horribly broken. Drew has disappeared. And Bobby and Ed think he was shot. The other mountain man must be up there on the cliffs above them, waiting, they think. It's up to Ed now to save their lives, and the only way he can do that is to climb the side of the gorge at night. He puts his bow over his back with the razor-sharp arrows in a quiver attached to the handle and starts the long ascent through the dark.

The actual Chattooga didn't have a suitable location for this action. But Tallulah Falls, not far away, was perfect. There was a hydroelectric dam about a half-mile upstream with gates that could adjust the ferocity of the torrent pouring through the gorge to suit the needs of the shot. The flow could be reduced to a trickle if need be. But it was still a dangerous place. The first half of the falls ended in a deep pool that you could swim or paddle across easily when the current was turned down. But the only way to walk to the other side of the gorge was on a slick, slightly submerged retaining wall twelve inches wide, with the pool on one side and a ninety-foot drop on the other. Everyone used the wall, holding on to a little rope for security. I still don't know why no one slipped when the water was low, or was washed over the precipice during filming when the river swelled across it in heavy waves. Maybe it was the luck of people who'd started to quit caring.

Burt, the former stuntman, wanted to take his own risks, do his own "gags." For the breakup of the canoes, special-effects man Marcel Vercoutere devised a catapult to launch Reynolds thirty feet in the air, hurling him toward the pool. He was well padded, but he was still pretty badly beaten up on the rocks. Jon Voight took to climbing the lower levels of the cliff without any safety equipment. One day Jon was about twenty feet above the crew when he lost his hold and tumbled back off the rocks. A prop man was able to break his fall, barely, but stood frozen for a few seconds before he let Voight go. Everybody was frozen. The exposed blade of a hunting arrow on Jon's bow quiver was a breath away from the prop man's throat.

It was like the whole film was becoming some kind of macho gamble in which each man was out to prove he could take the risks the characters were running, characters that James Dickey had only imagined.

At the top of the gorge, 150 to 250 feet above the rocks, the risks were even greater, and everybody played. As they searched for the best camera angles, Boorman and Zsigmond leaned way out over the edge of the precipice, and only rarely put on safety harnesses. Lives were risked to position lights, or to saw off a twig that blocked the lens.

In the story, Ed reaches the top of the cliff just before dawn. He sees the mountain man, rifle in hand, peering at the river below. Ed draws down on him. His hand starts to shake, just as it did with the deer. The mountain man sees him. Ed's only going to get this one shot. The mountain man fires, Ed releases, and you're not sure for several seconds if the arrow has hit him or not. Then the mountain man turns. You see the arrow in his chest and he falls to the ground. But Ed doesn't leave him there. All this killing, all these crimes have to be buried by the river. He uses a rope to lower the mountain man's body down the cliff and sink it in the pool.

The special-effects men thought they'd use a dummy for the scene of a corpse dangling and twisting at the end of a cord high on the side of the cliff. But the dummy looked too much like a dummy. "Would Cowboy do it himself?" someone asked as the mannequin was dragged back up over the ledge. Cowboy took a look at the drop. It was about two hundred feet at this point. He fingered the thin rope that would hold him. He shook his head. He took a swig of the Pabst Blue Ribbon beer he always had close at hand, and sighed, and nodded toward the dummy. "Well," he said, "I g-guess if he c-can do it so c-can I."

Members of the crew and the artificial family at Kingwood began to go home. An assistant producer, both assistant directors, a camera operator, and two nurses left for reasons of health, or weariness or frustration. Burt's Numero Uno left, too, during the most dangerous part of the filming. But it was so important to him to be seen with a woman, even if no woman was at hand, that one day he came to the set in Tallulah Gorge with a handful of love letters written to him by women who'd slept with him. He passed them around to the crew for their reading enjoyment. One collection was from a pair of girls who called themselves Franny and Zooey. Another, more depressing set of letters was from an exotic dancer in a Newport News service club who was trying to launch her son's career as a musician by having him play backup during her routines. Burt was going to be her ticket out of all that, she thought.

The filming moved back to the Chattooga for a last sequence on the roughest section of the river before the four surburbanites arrive on the still waters of the lake that is rising behind the fictional town of Aintry. One morning everybody arrived on the set to word that someone had been shooting at the trucks the night before. No one was hurt. Everyone was a little spooked. It added to the sense that the whole production was racing against time, against some impending disaster. But we were on the homestretch, and almost too tired to care.

When the shooting was on the river, the stand-ins were usually left waiting at pickup points to meet the actors' and camera crew when they came in off the water. We'd been most of the day at one of the roughest sections of the Chattooga when a heavyset kid everyone called Chicago borrowed a raft from the prop department and suggested we try shooting the rapids. It was midsummer now, and the only place you could see that was cool was in the water. We watched a couple of other members of the crew bounce downstream in inner tubes. They dropped over a ledge of about ten feet, twirled around for just a second in a whirlpool, then bounced out and headed on down the river. It looked like a safe enough thrill.

Chicago and I got into the raft and kicked out from shore. We hit the current and started to twirl slowly, picking up speed as we approached the drop. Now we were over the edge. And down. And the raft filled with water and we started to spin. It wasn't sinking, but it wasn't moving out of the whirlpool either. It was agitating and banging like a tennis shoe in a washing machine. One of the boys onshore threw us a rope, and Chicago grabbed it and went over the side. I saw him resurface downriver and get pulled in by the others like some enormous salmon. I was gulping water under the falls, and the raft was spinning and shaking too fast for me to think of anything now except how I was going to get out of it. I knew I couldn't make it swimming. I knew the hydraulic tumbler would drag me down to the bottom. I had to have the rope. The boys onshore were shouting and signaling. They were going to throw me the line, but I was supposed to tie it to the raft so they could pull it out. They threw. After a couple of tries, I caught. They left the line slack. But as the raft spun, the rope wrapped around my chest, my arms, my neck. I struggled to get it off, tried to find someplace to tie it, but it looped over my head and neck again. The water pounded from above, boiled up from below. The raft felt like it was going to tear apart. I freed my neck of the rope again and wrapped the end around my hand and went over the side. The current pushed me straight to the bottom, banging my body on the rocks, twirling me at the end of the cord that tightened like a noose around my hand and wrist. And then I was back on the surface, and being pulled in to shore. I guess I looked like hell: as gray as the rocks by the riverside. "We thought we'd lost you," said Chicago. "Me, too," I said.

It was about as close as I'd ever come to dying, at least at that point in my life, and that evening I tried to tell my father all about it. But he seemed to have other things on his mind. He was back on the scene. Back in the movie.

The shooting was almost over, and he'd been given a part to play on screen. He was going to be Sheriff Bullard, who doesn't really believe the story these city fellas tell him about what happened on the river -- "How come you boys to have four life jackets?" -- but lets them go anyway.

My father had never acted before. Not as such. And it embarrassed me then to watch him on the set. When I watch the movie now and see those scenes I think he was just about perfect: he is big and menacing, and there is a little of the Winslow sheriff in him; but there is also this genteel insecurity as Bullard tries to cope with the hinted atrocities taking place in his county, and there are several times in his brief appearance when he is just so much like my father, even the best of my father, sober and thoughtful and picking his words with real care, that I am glad just to be able to see him.

We were into the last days on the set. There was a last scene to shoot in which my father and I appear together, although it was later cut from the movie. Ed and Bobby and Lewis are called back up from Atlanta to the dam at Aintry. Lewis is on crutches. All of them are wearing business clothes, all have come to see a corpse on a stretcher covered by a sheet. Sheriff Bullard reaches down and lifts the shroud to show them the body of -- you're not sure. It could be one of the mountain men. It could be Drew. You don't know and you never do see. Ed wakes from the dream.

I was the corpse under the sheet.

Everyone was counting the hours until shooting was over. Some read scripts for future films, some wondered where their next jobs would come from, and a couple looked forward to retiring soon. The stars spent much of their time playing golf and gambling together, competing and performing still, but taking fewer risks. Voight and his girlfriend, Marshalene, were over at the Boormans' a lot, Ned and Belinha awaited the birth of their child. Ronny spent his evenings picking and singing for the country-club set at Kingwood. I had the impression Burt was picking up any woman who came to hand. He also went around buying property. Tom Priestley, the editor, secluded himself with a Moviola at the Heart of Rabun to turn out a rough cut from thousands of feet of film.

Then, when my father had finished his part and was getting ready to leave, he and I were very cordially invited to Boorman's house one morning to see what there was to be seen in the makeshift basement projection room. We were alone as we watched the product of three rugged months of work thrown on the screen. We drank beers, one after another. We took breaks between reels, and after the first couple Jim Dickey was ecstatic. By halfway through the movie he was shouting out loud; then, at the climax on the cliff top, he went completely quiet except for two brief moments when, his hand over his mouth, acting awestruck, he breathed, "My God. Oh, my God."

He was faking it, I thought. Trying to convince himself. He had lived with this story -- we had lived with it -- all these years, and then it had all been taken over by other people and made into something else. Jim Dickey wouldn't let anyone change a line of his poetry, and he'd been ferocious defending every comma in the manuscript of his novel. And now this. It was a good movie. Very good. But it wasn't the one he had had in his head.

The last reel over, the last beer drunk, we stumbled from the dark recesses of Boorman's cottage into the glaring Georgia summer light. We said goodbye to Boorman's family and walked up to Kingwood's desk. My father asked for his check, flirting with the pretty receptionist. She soon found the bill. "Warners is going to pay for this," he said. "I don't want to see the total." The girl laughed and slapped her hand over the sum as my father signed. Her little finger was missing.

Outside, I helped my father fit his tape recorders, bows, and typewriter into his car. He was smiling. "I think we've really got something in this film," he said a couple more times as he climbed into the driver's seat. He drove out past the golf course, onto the highway, and home to Columbia. A few days afterward, I followed, leaving behind Clayton's Hollywood-in-residence, its country clubs, dirt farmers, mountain men, and white water, leaving behind the country of the nine-fingered people.

Deliverancedid not hit the theaters for another year. There were technical problems with the scenes where Ed climbs the cliff. They were shot in the day, but were supposed to look like night. They did not. In the final version there is a weird, solarized halo around Voight throughout the sequence. There was also a dispute about the script. Boorman had changed so many lines during the shooting -- "Squeal like a pig!" -- that he wanted to share the writing credit, and the writer's money. The conflict went to arbitration, and James Dickey won. He got to keep all of the credit, all the cash.

When at lastDeliverance,the film, was at hand, I had to realize that James Dickey had not made this movie, he had let it make him. This man, this father-poet-god, who had always demanded of himself, and of me, such perfection, had settled for artistic compromises that he would never in his imagination have tolerated -- or forgiven -- in another poet, in a student, in his child. And he was not only settling for less, it seemed to me, he was reveling in the result.

The tremulous sense of uncertainty, the inchoate anger that I'd felt all through my adolescence began to focus now on the idea of betrayal. I felt the righteous fury of any young man whose ideals have been sullied, and, added to that, the ferocious intolerance that came with being James Dickey's son. And all of it was turning on him. Yet I could not get away. The attraction was too strong. I was drifting like a satellite in an erratic orbit, circling close, circling at a great distance, circling always within the pull of his enormous gravity.

I would go with him, in the end, even to the theaters whereDeliverancewas showing. He would wear his purple fringed leather jacket and his big Stetson hat with the pheasant-feather band. Sometimes the long strands of hair he combed over the top of his balding head would come loose and drop down over one ear, giving him the look of a cowboy who'd been half scalped. The smell of alcohol would ooze from his pores. And he would stand in the long lines -- even walk up and down the lines -- as people waited for tickets. "You see that?" he'd say. "That's my movie."

Copyright © 1998 by Christopher Dickey

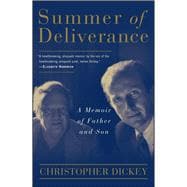

Excerpted from Summer of Deliverance: A Memoir of Father and Son by Christopher Dickey

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.