Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Prologue: What the Hell Is Going On Here? | p. 1 |

| The Northeast Philadelphia Story | p. 9 |

| The Northeast Philadelphia Story | p. 11 |

| A Call to Service | p. 26 |

| "Ten Years Out" | p. 34 |

| The Long Gray Line | p. 43 |

| Murphy's Law | p. 49 |

| The Brass Ring | p. 65 |

| Task Force Eagle | p. 67 |

| The Brass Ring | p. 89 |

| Who Killed Specialist Keith? | p. 100 |

| Hearts and Minds | p. 108 |

| The Golden Rule | p. 119 |

| Fridays in Never-Never Land | p. 130 |

| Allah's Will | p. 139 |

| Democracy 101 | p. 152 |

| The Heartache of Homecoming | p. 170 |

| Taking the Hill | p. 179 |

| The Home Front | p. 181 |

| A Different Kind of Service | p. 192 |

| Untouchable | p. 219 |

| All in | p. 237 |

| Epilogue | p. 251 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 264 |

| Index | p. 269 |

| Table of Contents provided by Blackwell. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter 1

It was after midnight on my first day in Baghdad when I was ordered to report to the office of Colonel Arnold Bray, commander of the 2nd Brigade Combat Team of the 82nd Airborne Division. For the next forty-five minutes, this tough 6'4" African-American warrior with two decades in the military—a man responsible for 3,500 paratroopers—described what I would face as the 2nd Brigade’s judge advocate general (JAG) leading a Brigade Operational Law Team (BOLT). He was damn proud of what the six-member BOLT team was already achieving, but knew that there was a tough road ahead—and he had high expectations of our team, our mission, and me.

“Make no mistake, what you and your team will do—or not do—to win the hearts and minds of these Iraqis will save our paratroopers’ lives,” he told me. “Get out there, be aggressive, go after it.” He described Captain Koby Langley, whom I was replacing, and praised his accomplishments in establishing a legal claims framework and cultivating relationships with Iraqis at the two courthouses in Al Rashid, Baghdad’s largest and poorest district, where we were based. “You need to take this team even further.”

As I listened, I couldn’t help noticing the heavy bags under his eyes. Like most paratroopers, he was visibly sleep-deprived; three other paratroopers went into his office after me that night, each for an extensive meeting. I was still getting acclimated to the time zone and our spartan accommodations, and no matter how much caffeine I pumped into my bloodstream, I struggled to keep my eyes open that night. Our duty day would be eighteen hours every day. For officers, it was bad form to get more than five hours of sleep per night. Any less would lead to dementia, and substantially reduced reaction time.

My education continued at the 7:00 a.m. battle update brief the next morning. These briefings—updating us on combat operations in our sector the night before and what was going on in the neighboring sectors throughout Baghdad—were the glue that held our brigade senior staff together. Our intelligence officer told of a taxicab driver who had been taken into custody after trying unsuccessfully to fire a rocket-propelled grenade into an Iraqi police station. When questioned about it, the driver admitted that he had been paid to carry out his crime—two hundred Iraqi dinar, the Iraqi currency, still imprinted with the head of Saddam Hussein. The lives of Iraqi police officers—and the stability of Iraq—were being threatened for the equivalent of less than one U.S. dollar.

That afternoon, a man showed up at the front gate of our forward-operating base (FOB), located just off Highway 8, a six-lane concrete-and-dirt highway known in our sector of south central Baghdad as Ambush Alley. Shouting that we had killed his nephew, he demanded to see Colonel Bray. His voice was rising, agitating the crowd of over fifty Iraqis at the gate, who had already been standing in the hot sun for hours and were becoming unruly.

The guards called for an interpreter, and Captain Langley and I walked outside the gate, carrying our M4s and dressed in our battle-rattle: Kevlar helmet and Interceptor body armor (IBA) vests. We identified the man and walked him back into the compound, under the watchful eye of the gunner on our roof. As we pushed our way back through the throng, we could hear cries of desperation in broken English: “Where is water?”; “Why no lights?”; “I thought you great Americans?”

I was puzzled. Why was this crowd of Iraqis standing here baking in the summer sun? What were they asking us for? Wasn’t there someplace we could send them? Weren’t we just in charge of security and combat operations?

There were no good answers. All we knew was that humanitarian organizations were in full retreat due to the escalating violence, and Jay Garner, the leader of the so-called interim government, the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, had just been fired. Thirteen weeks after our invasion and military commanders were left holding the bag, scrambling to create a mini Marshall Plan in the absence of support and direction from Washington and the Green Zone. The growing numbers of disgruntled Iraqis shaking the gates of every forward operating base in Iraq became a tactical nightmare. We were losing the battle for hearts and minds. An entire postwar reconstruction system had to be built from scratch—immediately.

I glanced up to the roof, eyeing the gunner, who was steadily scanning the crowd for signs of insurgent activity, and wondered, What the hell is going on here? These were trained combat paratroopers—the finest in the army. They had fought their way into the heart of Baghdad, and achieved one of the most stunning military victories in the history of warfare. And now they were being used to guard a base against civilians desperate for food, water, and some semblance of normalcy.

As we escorted the Iraqi into our compound, Captain Langley looked over at me. He must have recognized the look of incomprehension in my eyes. “Don’t worry,” he said, “you’re a paratrooper. Remember: Impossible is our regular workday.” I would later tell my team that we could spend our time in Iraq hiding from the reality, and the seeming impossibility of the situation, or we could spend it trying our Airborne best to make a difference. “They are going to give you some medal when you get back from this war,” I’d tell them. “Just make sure you earn it.”

When we got inside the compound, the Iraqi told us his story. Apparently, several nights earlier, the 82nd Airborne had conducted a cordon and search in an area where our intelligence indicated insurgents were living or operating. In that type of operation, U.S. forces cordon off a city block or two from pedestrians and vehicles, make a bullhorn announcement in Arabic that everyone should stay indoors, and proceed to search buildings in the restricted area for weapons, hostages, or suspected insurgents.

On the night in question, paratroopers planted themselves on rooftops, scoping out possible threats in the cordoned-off zone. Suddenly, one of them noticed an Iraqi male carrying a machine gun emerge onto a rooftop several houses away on the other side of the street. The Iraqi’s head turned as he appeared to gaze down to where other paratroopers were entering the building below him. Even with night-vision goggles, it was hard to gauge from across the street what the Iraqi was doing with the weapon, but it appeared he was focusing his aim on our soldiers, preparing to fire.

The paratroopers got on their radios: “Potential target ten o’clock at southern rooftop!” “Potential engagement of friendlies.” “Confirm weapon?” asked a paratrooper, not knowing how long he had before the Iraqi took his shot. The squad leader answered immediately from a nearby location, “Weapon confirmed.” “Take out the hostile,” someone shouted over the radio. Shots rang out from an M4. The Iraqi fell to the ground.

Within seconds, paratroopers rushed into the building and climbed the back staircase. Meanwhile, another Iraqi man appeared on the rooftop, retrieved the weapon our paratroopers had seen and vanished back into the building. When our troops raced inside a few moments later, the Airborne medic reported over the radio that the fallen Iraqi was a twelve-year-old boy, whose mother was now holding him in her arms, shouting in Arabic. The mother was hysterical, tears streaming down as she wailed, anguish on her face. She refused to let the medic treat her son, clutching his lifeless body to her chest and rocking back and forth. Finally she relented, and the nineteen-year-old medic checked the boy’s vital signs. He was dead.

The boy’s name, we learned, was Mohammed al-Kubaisi. The man who came to our base was his uncle. Colonel Bray is an old-school warrior, but at that meeting he spoke not as a soldier or paratrooper, but as a father. He took off his Kevlar helmet and sat with the boy’s uncle on our ragged office couch. “I have a son of my own,” he told him. “I know my words ring hollow, but please know that we all grieve for your loss.” Colonel Bray placed his hand on his IBA vest right over his heart, patting it as he spoke to convey his sympathy. His words were translated for the uncle, and the pain on his face eased ever so slightly.

Colonel Bray knew his paratroopers were acting in self-defense in the dead of night, eight thousand miles from home. He was not going to second-guess them. Neither was I. When Mohammed’s uncle first came to talk with us, he claimed that the killing was unnecessary because Mohammed had not been carrying a weapon. Later, he conceded that Mohammed had been carrying a weapon, but explained that the boy had only been trying to hide it—not fire it at U.S. troops. Perhaps this is true. But given the imperfect knowledge that the paratroopers had that night, our troops made the only decision they could have under our rules of engagement and international law; they have an inherent right of self-defense, and they perceived an imminent and hostile threat. In war, even the best judgment often has terrible consequences.

The whole case left me with a profound unease. It reminded me of the words spoken by Israeli prime minister Golda Meir: that when peace finally comes, it will be easier to forgive our enemies for killing our sons and daughters than it will be to forgive them for making us kill theirs. When Mohammed’s uncle left our office, I felt—as I am sure my fellow soldiers felt—that we had just made our own mission in Iraq more difficult.

When Vivienne Walt, a Boston Globe reporter, caught up with the al-Kubaisi tribal leader (called a sheikh) a few months later, the sheikh told her that Mohammed’s family had still not received payment from the U.S. government for their loss and was considering retaliation.

“If they don’t pay our settlement, we’ll kill four of them,” he said, sitting in his office near the Tigris River. “The Americans are like a tribe for us.”

Back then, most Iraqis would probably have disagreed with this sheikh and opposed attacks on American forces. Now, the majority of Iraqis believe it’s acceptable to kill Americans.

I had come face-to-face with the deadly reality of the poorly planned Bush war. It was a cruel twist on the Pottery Barn rule General Colin Powell had invoked: The Bush administration broke it, but it was the soldiers on the ground who had to pay the price—picking up the pieces, the shambles, of the president’s failed plan.

I forced this thought from my head. I was only a captain, and I was here to complete my mission and lead my team, no matter what. But I later learned that nearly every officer worth his or her salt in southern Baghdad felt the same way the day they set foot in Iraq. You did not need to be a brigade commander or a general to be aware of the hornet’s nest we had stirred up. It was a horrible feeling, like being strapped beneath a slowly dropping pendulum ax, seeing death in front of you, steadily creeping closer, and unable to move to the left or right.

But we had signed an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. We were there to fight, and we wouldn’t back down, even in the face of impossible odds. It was that warrior spirit, epitomized in every paratrooper I served with, that George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld were no doubt relying on when they left the multibillion-dollar reconstruction plans on the cutting room floor—too expensive, they thought, and not sellable to the American public.

It has cost far more now.

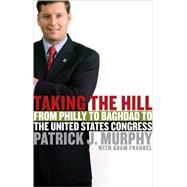

When I returned from Iraq in January 2004, I knew we needed a change of course. In time, I realized the best way that I could help bring about that change was to run for Congress. Two years later, I became the first Iraq War veteran to serve in our nation’s capital. The district I represent, the Eighth Congressional District of Pennsylvania, includes the neighborhood in Northeast Philly where I grew up, a kid who took fist fights more seriously than schoolwork. It was in that neighborhood that I learned the values—service, honor, family—that I carried with me as a law professor at West Point, as a captain in the 82nd Airborne, and today, as a U.S. congressman.

That is my story. And this is how it happened. This is how I took the hill.

Copyright © 2008 by Patrick J. Murphy. All rights reserved.

Excerpted from Taking the Hill: From Philly to Baghdad to the United States Congress by Patrick J. Murphy

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.