The year was 1979 and the fifteen teenagers on the Crenshaw High Cougars were the most talented team in the history of high school baseball. They were pure ballplayers, sluggers and sweet fielders who played with unbridled joy and breathtaking skill.

The national press converged on Crenshaw. So many scouts gravitated to their games that they took up most of the seats in the bleachers. Even the Crenshaw ballfield was a sight to behold -- groomed by the players themselves, picked clean of every pebble, it was the finest diamond in all of inner-city Los Angeles. On the outfield fences, the gates to the outside stayed locked against the danger and distraction of the streets. Baseball, for these boys, was hope itself. They had grown up with the notion that it could somehow set things right -- a vague, unexpressed, but persistent hope that even if life was rigged, baseball might be fair.

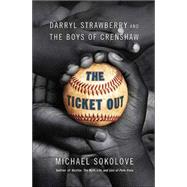

And for a while it seemed they were right. Incredibly, most of of this team -- even several of the boys who sat on the bench -- were drafted into professional baseball. Two of them, Darryl Strawberry and Chris Brown, would reunite as teammates on a National League All-Star roster. But Michael Sokolove's The Ticket Out is more a story of promise denied than of dreams fulfilled. Because in Sokolove's brilliantly reported poignant and powerful tale, the lives of these gifted athletes intersect with the realities of being poor, urban, and black in America. What happened to these young men is a harsh reminder of the ways inspiration turns to frustration when the bats and balls are stowed and the crowd's applause dies down.

Just as Friday Night Lights portrayed the impact of high school sports on the life of a Texas community, and There Are No Children Here examined the viselike grip of poverty on minority youngsters, The Ticket Out presents an unforgettable tale of families grasping for opportunities, of athletes praying for one chance to make it big, of all of us hoping that the will to succeed can triumph over the demons haunting our city streets.

The year was 1979 and the fifteen teenagers on the Crenshaw High Cougars were the most talented team in the history of high school baseball. They were pure ballplayers, sluggers and sweet fielders who played with unbridled joy and breathtaking skill.

The national press converged on Crenshaw. So many scouts gravitated to their games that they took up most of the seats in the bleachers. Even the Crenshaw ballfield was a sight to behold -- groomed by the players themselves, picked clean of every pebble, it was the finest diamond in all of inner-city Los Angeles. On the outfield fences, the gates to the outside stayed locked against the danger and distraction of the streets. Baseball, for these boys, was hope itself. They had grown up with the notion that it could somehow set things right -- a vague, unexpressed, but persistent hope that even if life was rigged, baseball might be fair.

And for a while it seemed they were right. Incredibly, most of of this team -- even several of the boys who sat on the bench -- were drafted into professional baseball. Two of them, Darryl Strawberry and Chris Brown, would reunite as teammates on a National League All-Star roster. But Michael Sokolove's The Ticket Out is more a story of promise denied than of dreams fulfilled. Because in Sokolove's brilliantly reported poignant and powerful tale, the lives of these gifted athletes intersect with the realities of being poor, urban, and black in America. What happened to these young men is a harsh reminder of the ways inspiration turns to frustration when the bats and balls are stowed and the crowd's applause dies down.

Just as Friday Night Lights portrayed the impact of high school sports on the life of a Texas community, and There Are No Children Here examined the viselike grip of poverty on minority youngsters, The Ticket Out presents an unforgettable tale of families grasping for opportunities, of athletes praying for one chance to make it big, of all of us hoping that the will to succeed can triumph over the demons haunting our city streets.