| Preface | |

| The Buddhist Understanding of Suffering | p. 1 |

| His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso the Fourteenth Dalai Lama: The Transformation of Suffering | p. 15 |

| His Holiness Pope John Paul II: The Meaning of Suffering | p. 27 |

| The Wisdom of the Cross | p. 35 |

| Abandonment and Love | p. 51 |

| Love, Compassion, and Communion | p. 63 |

| Emotional Healing: From a Sense of Unworthiness to Self-Acceptance | p. 83 |

| Freedom from Attachments: From Consumerism to Compassion | p. 119 |

| Overcoming Violence: From Anger to Communion | p. 141 |

| Accepting Sickness and Aging: From Resistance to Letting Go | p. 183 |

| Facing Death: The Final Journey from Fear to Peace | p. 209 |

| Building a Culture of Dialogue and Peace | p. 231 |

| Epilogue | p. 241 |

| List of Contributors | p. 245 |

| Index | p. 263 |

| Table of Contents provided by Blackwell. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

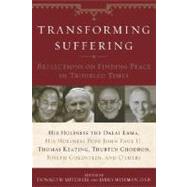

Excerpted from Transforming Suffering: Reflections on Finding Peace in Troubled Times by His Holiness the Dalai Lamma, His Holiness Pope John Paul II, Thomas Keating, Joseph Goldstein, Thubten Chodro by Donald W. Mitchell, James Wiseman

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.