Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Map of Tuxedo Park | p. xii |

| Preface | p. xv |

| The Patron | p. 1 |

| Bred in the Bone | p. 16 |

| The Power Broker | p. 37 |

| Palace of Science | p. 55 |

| Cash on the Barrel | p. 80 |

| Restless Energy | p. 108 |

| The Big Machine | p. 133 |

| Echoes of War | p. 154 |

| Precious Cargo | p. 179 |

| The Blitz | p. 209 |

| Minister Without Portfolio | p. 238 |

| Last of the Great Amateurs | p. 251 |

| Epilogue | p. 290 |

| Alfred L. Loomis' Scientific Publications | p. 299 |

| Author's Note on Sources | p. 303 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 311 |

| Index | p. 313 |

| Table of Contents provided by Rittenhouse. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Ward was smiling but that did not mean that he was amused. The smile was a velvet glove covering his iron determination to get under way without any lost motion.

-- WR, fromBrain Waves and Death

On January 30, 1940, shortly after ten P.M., the superintendent of the building at 116 East 83rd Street noticed that a bottle of milk delivered that morning to one of his tenants had remained in front of the door all day. The young man who rented the three-room apartment had not said anything about going out of town. He was a conspicuous fellow, extremely tall -- at least six feet four -- and lean, with piercing blue eyes and a shock of dark hair. After knocking repeatedly and failing to get an answer, the superintendent notified the police.

William T. Richards was found dead in the bathtub with his wrists slashed, blood from his wounds garlanding the walls of the bathroom. He was dressed in his pajamas, his head resting on a pillow. A razor blade lay by his hand. He was a former chemistry professor at Princeton University who was currently employed as a consultant at the Loomis Laboratory in Tuxedo Park, New York. He was thirty-nine years old. His personal papers mentioned a mother, Miriam Stuart Richards, living in Massachusetts, and the detective at the scene asked the Cambridge police to contact her. AsThe New York Timesreported the following morning, William Richards was from a prominent Boston family, son of the late professor Theodore William Richards of Harvard, winner of a Nobel Prize in chemistry, and the brother of the former Grace (Patty) Thayer Richards, wife of the president of Harvard, James B. Conant.

Although his death was clearly a suicide, everything possible was done to hush up the more unpleasant aspects of the event, and the Boston papers never published the details. Richards' brother, Thayer, was immediately dispatched to New York, and he saw to it that most of what had transpired was concealed from his mother and sister. A suicide note that was found by the tub was destroyed, and its contents were never revealed. The Richards family was naturally concerned about its reputation, but there were also pressing concerns, of a rather delicate nature, that made it vitally important that Bill's suicide be kept as quiet as possible. Miriam Richards, desperate to avoid any scandal, drafted a reassuring letter attempting to put the untimely death of her son in a better light, copies of which she sent out to important friends and relations. She explained that Bill had long been "nervously, seriously ill" and had never properly recovered from severe abdominal surgery several years earlier. She also supplied him with an end that left open the possibility that his death was accidental, writing that "Bill died of an overdose of a sleeping draught." It is entirely possible that this is what she had been told.

"William Theodore Richards was beyond any doubt one of the most brilliant members of our class," began his Harvard obituary, based on the fond reminiscences of his friends and scientific colleagues. He was interested in new scientific phenomena, the originality of his ideas leading him into experimental work. But he had the kind of restless, wide-ranging intelligence -- he was a talented painter and musician and briefly considered playing the cello professionally -- that made him, according to one friend, "a veritable Renaissance man." He was a chemist at his father's insistence, but his heart was not in it, and he found it difficult to force himself to undertake the routine proofs and laborious accumulation of data that would have given him more publishable material and more recognition in his field. He had "a mentality which could be called great," wrote his classmate Leopold Mannes, a fellow scientist and musician, who speculated that Richards despaired of ever meeting the onerous demands he imposed on himself. "In his attitude towards life, towards science, towards music -- of which he had an astounding knowledge and perception -- and towards literature, he was a relentless perfectionist, and thus his own implacable judge. No human being could be expected fully to satisfy such standards."

Richards was a solitary man, confining his friends to a small, clever circle. He kept most of his contemporaries at bay with his caustic wit, which made quick work of any human frailty, whether at his own expense or someone else's. With complete abandon, he would ruthlessly mimic anyone from Adolf Hitler to some sentimental woman who had been foolish enough to confide in him. To most, he seemed cordial, cold, and a bit superior, his moodiness exacerbated by periods of poor health and depression. He eventually quit his job at Princeton and moved to New York, where he worked part-time as a chemical consultant while devoting himself to an arduous course of psychotherapy. The Harvard memorial notes concluded that "after a brave struggle for ten years to overcome a serious neurosis, which in spite of treatment grew worse, Bill died by his own hand."

Richards' death was nevertheless "shocking" to Jim Conant and his wife, Patty. Richards had celebrated Christmas with them only a few weeks before and had stayed in the large brick mansion at 17 Quincy Street that was the official residence of the Harvard president. Although his psychological condition had always been precarious, he had seemed "to be making real progress," his mother later lamented in a letter to a close family friend, so much so that "last summer and autumn he was so happy and well that for fun he wrote a detective story." Richards had submitted the manuscript to Scribner's, which "had at once accepted it."

Just a few weeks after he took his own life, his book, Brain Waves and Death, was published under the pseudonym "Willard Rich." It was, in most respects, a conventional murder mystery, with the added interest of being set in a sophisticated modern laboratory, where a group of eminent scientists are hard at work on an experiment designed to measure the electrical impulses sent out by the brain. In a twist on the standard "hermetically sealed room" problem, Richards staged the murder in a locked experimental chamber that is constantly monitored by highly sensitive listening devices and a camera. The book earned respectful reviews, withThe New York Timesdescribing the story as "ingeniously contrived and executed" and awarding Willard Rich "an honorable place in the ranks of mystery mongers." None of the critics were apparently aware that the author was already dead or that he had rather morbidly foreshadowed his imminent demise in the book, in which the first victim is a tall, arrogant young chemist named Bill Roberts.

At the time, only a small group of elite scientists could have known that while the method Richards devised to kill off his literary alter ego was of his own invention -- a lethal packet of poison gas that was frozen solid and released into the atmosphere when warmed to room temperature -- the actual science and the laboratory itself were real. George Kistiakowsky, a Harvard chemistry professor and one of Richards' closest friends and professional colleagues, guessed the truth immediately, "that it was a take-off on the Loomis Laboratory and the characters frequenting it." Despite its contrived plot, the book was essentially a roman à clef. No one who had ever been there could fail to recognize that the "Howard M. Ward Laboratory" was in reality the Loomis Laboratory in Tuxedo Park and that the charismatic figure of Ward himself was transparently based on Alfred Lee Loomis, the immensely wealthy Wall Street tycoon and amateur physicist who, among his myriad inventions, claimed a patent for the electroencephalograph, a device that measured brain waves.

The opening paragraphs of the book perfectly captured Loomis' rarefied world, where scientists mingled with polite society and where intellectual problems in astronomy, biology, psychiatry, or physics could be discussed and pursued in a genteel and collegial atmosphere:

The Howard M. Ward Laboratory was not one of those hospital-like institutions where Pure Science is hounded grimly and humorlessly as if it were a venomous reptile; the grounds of the Laboratory included a tennis court, bridle paths, and a nine-hole golf course. Guests there did not have to confine themselves to science, they could live fully and graciously.

It was Richards who had first told Kistiakowsky about Loomis' private scientific playground in Tuxedo Park, a guarded enclave of money and privilege nestled in the foothills of the Ramapo Mountains. Tuxedo Park, forty miles northwest of New York City, had originally been developed in 1886 by Pierre Lorillard, the tobacco magnate, as a private lakefront resort where his wealthy friends could summer every year. The rustic retreat became the prime meeting ground of American society, what Ward McCallister famously called "the Four Hundred," where wealthy moguls communed with nature in forty-room "cottages" with the required ten bedrooms, gardens, stables, and housing for the small army of servants required for entertaining in style. Leading members of the financial elite, such as Rockefellers and Morgans, numbered among its residents, as did Averell Harriman, who occupied a vast neighboring estate known as Arden. Over the years, Tuxedo Park, with its exclusive clubhouse and fabled balls, had taken on all of the luster and lore of a royal court, and although it had dimmed somewhat since the First World War, it still regarded itself as the Versailles of the New York rich.

Loomis, a prominent banker and socialite, was very much part of that world and owned several homes there. According to Richards, however, Loomis was also somewhat eccentric and disdained the glamorous swirl around him. He had developed a passion for science and for some time had been leading a sort of double life: as a partner in Bonbright & Co., the thriving bond investments subsidiary of J. P. Morgan, he had amassed a substantial fortune, which allowed him to act as a patron somewhat in the manner of the great nineteenth-century British scientists such as Charles Darwin and Lord Rayleigh. To that end, Loomis had purchased an enormous stone mansion in Tuxedo, known as the Tower House, and turned it into a private laboratory where he could give free rein to his avocation -- primarily physics, but also chemistry, astronomy, and other ventures. He entertained lavishly at Tower House and invited eminent scientists to spend long weekends and holidays as his guests. More to the point, as Richards told Kistiakowsky, Loomis also extended his hospitality to "impecunious" young scientists, offering them stipends so they could enjoy elegant living conditions while laboring as skilled researchers in his laboratory.

Richards had seen to it that Kistiakowsky -- "Kisty" to his pals -- secured a generous grant from the Loomis Laboratory. The two had met and become fast friends at Princeton in the fall of 1926, when as new chemistry teachers they were assigned to share the same ground-floor laboratory. They were both tall, physically imposing men, with the same contradictory mixture of witty raconteur and reserved, introspective scientist. In no time they had discovered a mutual fondness for late night philosophizing and bathtub gin. As this was during Prohibition, the Chemistry Department had to sponsor its own drinking parties, and the two chemists "doctored" their own mixture of bootleg alcohol and ginger ale with varying degrees of success. Richards, who was subsidized by his well-heeled Brahmin family, had soon noticed that his Russian colleague, a recent émigré who sent money to his family in Europe, was having difficulty managing on the standard instructor's salary of $160 a month. Knowing any extra source of funds would be welcome, Richards had put in a good word with Loomis, just as he had when recommending Kistiakowsky to his "uncle Lawrence" -- A. Lawrence Lowell, who was then president of Harvard, and Bill's uncle on his mother's side. Grinning into the phone, he had provided assurances that Kistiakowsky was not some "wild and woolly Russian" and, despite being just off the boat, was "wholly a gentleman, had proper appearance and table manners, etc."

Richards' own introduction to Loomis had happened quite by accident a few months prior to his arrival at Princeton. While Richards was completing his postdoctoral studies at Göttingen, he had been sitting in the park one Sunday morning, idly readingChemical Abstracts,when a paragraph briefly describing an experiment being carried on in the "Loomis Laboratory" had caught his eye. He had immediately sent off a letter to the laboratory, "suggesting that certain aspects of the experiment could be further developed," and he had even outlined what the result of this development would probably be. Some months later, he received a response from the laboratory informing him that they had carried out his suggestions and the results were those he had anticipated. This had been followed by a formal invitation to work at the Loomis Laboratory.

Over the years, Richards and Kistiakowky had often commuted from Princeton to Tuxedo Park together on weekends and holidays and had conducted some of their research experiments jointly. Richards had arranged for them both to spend the summer of 1930 as research fellows at the Loomis Laboratory. What a grand time that had been. Not only was the room and board better than that of any resort hotel, but weekend recreation at Tower House -- when the restriction against women was relaxed -- included festive picnics, drinks, parties, and elaborate black-tie dinners. Back then, they had both been ambitious young chemists at the beginning of their careers and had reveled in the chance to work with such legendary figures as R. W. Wood, the brilliant American experimental physicist from Johns Hopkins, whom Loomis had lured to Tuxedo Park as director of his laboratory. Working alongside Loomis and a long list of distinguished collaborators, they had carried out series of original experiments, including some of the first with intense ultrasonic radiation, and had proudly seen their lines of investigation published in scientific journals and taken up by laboratories in America and Europe.

Kistiakowsky, who by then had joined Harvard's Chemistry Department and become close friends with Conant, never publicly revealed that Richards' book was based on Loomis and the brain wave experiments conducted at Tower House. In his carefully composed entry in Richards' Harvard obituary, he made only a passing reference to a "Mr. A. L. Loomis of Tuxedo Park," diplomatically noting that Richards' work at the laboratory had afforded him "one of the keenest scientific pleasures of his career." However, it is typical that he could not resist dropping one hint. Observing that very few physical chemists possessed his late friend's keenness of mind, Kistiakowsky concluded that no one could ever match Richards' own concise presentation of his work, "which was always done in the best literary form."

At the time of Richards' death, Kistiakowsky was still working for Loomis on the side. But the stakes were much higher now, and the project he had undertaken was so secret, and of such fearful importance, that Richards' parody of the Loomis Laboratory must have struck him as a wildly precipitous and ill-conceived prank. Richards had always thumbed his nose at authority and convention and had been disdainful of the narrow scope of his scientific colleagues, whom he once complained talked about "nothing but the facts, the fundamental tone of life, while I prefer the inferred third harmonic." But for Kistiakowsky, a White Russian who at age seventeen had battled the advancing Germans at the tail end of World War I, and then fought the Bolsheviks before being wounded and forced to flee his country, the prospect of another European war took precedence over everything. While in the past he might have joined Richards in poking fun at Loomis and his collector's attitude toward scientists, Kistiakowsky now appreciated him as a man who knew how to get things done. Loomis was a bit stiff, with the bearing of a four-star general in civilian clothes, but he was strong and decisive.

Kistiakowsky did not have to be told to be discreet, though he may have been. Loomis was furious about the book and threatened to sue for libel. He was an intensely private man and was horrified at the breach of trust from such an old friend. Richards had been a regular at the Tower House for more than ten years and was intimately acquainted with the goings-on there. In the months directly preceding his suicide, Loomis had plunged the laboratory into highly sensitive war-related research projects. Loomis wanted no part of the gossip and notoriety that might result either from Richards' unfortunate death or his book.

Neither did Jim Conant, who regarded the book as a source of acute embarrassment. It was bad enough that his wife's family continuously vexed him with their financial excesses and emotional crises, here was his brother-in-law stirring up trouble from the grave with this incriminating tale. Patty Conant was so distressed that she begged her brother, Thayer, to have the book recalled at once. But it was too late for that, and it was not long before Conant discovered thatBrain Waves and Deathwas not Richards' only legacy.

With his instinctive ability to home in on the latest developments on the frontiers of research, Richards had followed up his first book with something far more sensational. Among the papers collected from his apartment after his death was the draft of a short story entitled "The Uranium Bomb." It was written once again under the pseudonym Willard Rich. The slim typed manuscript, bearing the name and address of his literary agent, Madeleine Boyd, on the front cover, was clearly intended for publication. Richards was an avid reader ofAstounding Science Fictionand probably intended to place his story in the magazine, which regularly carried the futuristic visions of H. G. Wells and was a popular venue for the doomsday fantasies of scientists who were themselves good writers. Richards' story opens with the meeting in March 1939 between a rather callow young chemist named Perkins (Richards) and a Russian physicist named Boris Zmenov, who tries to enlist the well-connected American to warn his influential friends, and ultimately the president, "to suppress a threat to humanity." The Zmenov character, who is convinced the Nazis want to build a bomb, explains that there had been a breakthrough in atomic fission: the uranium nucleus had been split up, with the liberation of fifty million times as much energy as could be obtained from any other explosive. "A ton of uranium would make a bomb which could blow the end off Manhattan island."

Richards outlined Zmenov's theory, "tossed off with the breezy impudence of a theoretical physicist," describing the principles of atomic fission and the chain reaction by which an explosion spreads from a few atoms to a large mass of material, thereby generating a colossal amount of power. When Perkins professes disbelief, Zmenov becomes furious: "I am on the verge of developing a weapon," he declares, "which will be the greatest military discovery of all time. It will revolutionize war, and make the nation possessing it supreme. I wish that the United States should be this nation, but am I encouraged? Am I assisted with the most meager financial support? Bah."

As Conant read the manuscript, he realized it was an accurate representation of the facts as far as they were known. While not exactly common knowledge, Conant was aware that a great deal of information about uranium had been leaking out in scientific conferences and journals over the past year. His brother-in-law could have easily picked up many of his ideas just from readingThe New York Times,which had extensively covered the lecture appearances of the Danish physicist Niels Bohr and his outspoken remarks about the destructive potential for fission. Even Newsweek had reported that atomic energy might create "an explosion that would make the forces of TNT or high-power bombs seem like firecrackers." For his part, Conant, an accomplished scientist who had been chairman of Harvard's Chemistry Department before becoming president of the university, was far from convinced atomic fission was anywhere near to being used as a military weapon. He was still inclined to believe the only imminent danger from fission was to some university laboratories. But he was not ready to dismiss it, either.

Richards' story was disturbing, and if it cut as close to the bone as his novel had, it was potentially dangerous. There were too many familiar names for comfort, including an acquaintance "prominent in education circles" by the name of "Jim," which Conant must have read as a sly reference to himself. More troubling still, the physical description of Zmenov -- very short, round, and excitable -- matched that of the Hungarian refugee scientist Leo Szilard, who was known to be experimenting with uranium fission at Columbia University in New York. Szilard was always agitating within the scientific community about the importance of fission and had even formed his own association to solicit funds for his work. In a scene that rang especially true, Perkins arranges for Zmenov to meet a wealthy banker, and Zmenov is crestfallen when he does not pull out his checkbook. "Perhaps Zmenov thought all bankers were crazy to find something to sling their money into," Richards wrote in yet another thinly disguised account of Loomis' exploits. This time, Harvard's cautious president did not wait for Loomis to tell him that the story revealed too great a knowledge of high-level developments in the scientific world, and at the very moment external pressures were coming to a peak. Conant made sure the story was suppressed.

Conant was too guarded to ever fully confide his doubts in anyone, but he expressed some of his reservations to his son, Ted, who was thirteen years old at the time. The boy had come across the story when going through the boxes of books and radio equipment Richards had left to him and insisted that it ought to be published according to the wishes of his beloved uncle. Anything short of that, he argued, "was censorship." The fierce row between father and son that followed was memorable because it was so rare. Conant was a calm, controlled man who rarely lost his temper. He was also coldly practical and not given to old-fashioned sentiment. His angry retort that Richards' story was "outlandish" and "unworthy of him," coupled with his uncharacteristic claim that "the family honor was at stake," suggested there was something more to his opposition than he was letting on. His son reluctantly let the matter drop.

By the time Conant discovered Richards' manuscript, many of the events described in the story, although slightly distorted, had in fact already transpired. Szilard had befriended Richards and was regularly updating him on the work he was carrying on with the Italian émigré physicist Enrico Fermi, who had won a Nobel Prize and had recently joined the staff of Columbia University. After the French physicist Frédéric Joliot-Curie published his findings on uranium fission, Fermi lost patience with Szilard's passion for secrecy and insisted that their recent experiments be published. In a hasty note to Richards on April 18, 1939, Szilard broke the news:

Dear Richards: --

It has now been decided to let the papers come out in the next issue ofPhysical Review,and I wanted you to be informed of this fact.

With kind regards,

yours,

[Leo Szilard]

As Richards cynically noted in his story, Szilard's interest in him was primarily as a link to private investors like Loomis, whom Szilard desperately wanted to bankroll the costly experiments he planned to do at Columbia University. At the same time, Szilard had been busy wooing other Wall Street investors, enticing them with the promise of cheap energy. In a letter to Lewis L. Strauss, a New York businessman interested in the atom's commercial potential, Szilard wrote tantalizingly of "a very sensational new development in nuclear physics" and predicted that fission "might make it possible to produce power by means of nuclear energy." At one point, Szilard arranged for himself and Fermi to have drinks at Strauss' apartment and asked Strauss to invite his wealthy acquaintance Lord Rothschild, but the two physicists could not persuade the English financier to underwrite their chain reaction research. Part of the problem was that while Szilard needed backers, he was desperately afraid Germany would realize fission's military potential first. He was obsessed with secrecy. He was determined to protect his discoveries and cloaked his project in so much mystery that he often appeared as "paranoid" as Richards portrayed him in his sharp caricature. After all his efforts to find private investors had met with failure, Szilard wrote to Richards on July 9, 1939, pleading for money to prove "once and for all if a chain reaction can be made to work." His tone was urgent:

Dear Richards:

I tried to reach you at your home over the telephone, but you seemed to be away, and so I am sending this letter in the hope that it might be forwarded to you. You can best see the present state of affairs concerning our problem from a letter which I wrote to Mr. Strauss on July 3rd, a copy of which I am enclosing for your information and the information of your friends. Not until three days ago did I reach the conclusion that a large scale experiment ought to be started immediately and would have a good chance of success if we used about $35,000 worth of material, about half this sum representing uranium and the rest other ingredients...I am rather anxious to push this experiment as fast as possible...I would, of course, like to know whether there is a chance of getting outside funds if this is necessary to speed up the experiment, and if you have any opinion on the subject, please let me know.

If you think a discussion of the matter would be of interest I shall of course be very pleased to take part in it...Please let me know in any case where I can get hold of you over the telephone and your postal address.

During the summer of 1939, Szilard and Fermi worked out the basis for the first successful chain reaction in a series of letters. Encouraged by their correspondence, but frustrated by his continued failure to enlist any financial support for his experiments, Szilard turned to his old mentor, Albert Einstein, for help. Einstein was sixty years old and famous, someone with enough stature to lend credibility to his cause. After meeting with Szilard and reviewing his calculations, Einstein was quickly persuaded that the government should be warned that an atomic bomb was a possibility and that the Nazis could not be allowed to build such an unimaginably powerful weapon. On August 2, Szilard drafted the final version of the letter Einstein had agreed to send to the president. Szilard called a part-time stenographer at Columbia named Janet Coatesworth and, speaking over the telephone in his thick Hungarian accent, dictated the letter to "F. D. Roosevelt, president of the United States," advising him that "extremely powerful bombs of a new type" could now be constructed. By the time Szilard read her the signature, "Yours very truly, Albert Einstein," he was fully aware that the young woman thought he was out of his mind. That incident, no doubt exaggerated in Szilard's gleeful retelling, bears close resemblance to a passage in Richards' story in which a young secretary comes to see Perkins and confides her concerns about Zmenov. "I'm afraid he's getting himself into the most dreadful trouble," she tells him. "You know how impetuous he is. He's a genius, and when other people don't see that, he gets impatient."

Einstein's letter to Roosevelt would result in the convening of a government advisory committee to study the problem. Roosevelt appointed Lyman J. Briggs, director of the National Bureau of Standards, the government's bureaucratic physics laboratory, as chairman. On October 21, 1939, Szilard went to Washington and reported to the first meeting of the Briggs Advisory Committee on Uranium. He explained how his chain reaction theory worked and put in his usual plea for funds to conduct a large-scale experiment -- the same test he had been writing to Richards about for months. To Szilard's astonishment, the committee agreed to give him $6,000 for his uranium research.

Even then, Szilard did not cease his efforts at fund-raising and kept up his letters and calls to promising prospects. Twelve days after the meeting in Washington, he sent a brief note to Richards and included an eight-page memorandum for his "personal information only," summing up his report to the Briggs committee. The memo laid out exactly how much uranium and graphite he and Fermi would need for their experiments, how much it would probably cost, and which companies could supply the materials -- a blueprint for building a bomb. "It seems advisable we should talk about these things in greater detail before you take up the matter with a third person..."

Szilard was never able to pin down the elusive Loomis, who a few months later would decide to back Fermi's chain reaction research. Four years later, Szilard wrote to Loomis directly, requesting an appointment to see him, and recalled his previous attempts to contact him: "I regretted very much not having been able to meet you in March and again in July of 1939 and am inclined sometimes to think that much subsequent trouble would have been avoided if a contact with you had been established at that time."

There are no records indicating whether Conant had any knowledge of Szilard's regular correspondence with Richards or his attempts to use him as a conduit to Loomis. But by the spring of 1940, when Conant found Richards' story, any public mention of atomic energy's military potential would have made the Harvard president uneasy. War had overtaken Europe, and there was already speculation about how long England would be able to fend off a German invasion. Although America was still resolutely isolationist, Conant and other leading scientific advisers to the president had been working to keep the government informed of any new developments of importance to national defense. The Briggs committee had been formed in response to the growing concern about how far along the Germans were in their atomic research. Many noted physicists, including Niels Bohr and Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, two Hungarians now teaching in the United States, were urging their European colleagues -- notably the French nuclear scientist Frédéric Joliot-Curie, the Viennese physicist Erwin Shrödinger, and the British physicist Paul Dirac -- to exercise caution and were pushing for a publication ban on uranium fission. At the same time, Vannevar Bush, a tough-minded Yankee engineer who had recently resigned the vice presidency of MIT to head the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C., was agitating for "an accelerated defense effort." Alarmed that the United States military was technologically unprepared for war, Bush was exploring ways to mobilize the country's scientists for war.

Conant was aware that Loomis was in the thick of these talks. With close ties in the worlds of finance, government, and science, Loomis had virtually unprecedented access to the men who would ultimately decide the country's future. Not only was he a tycoon with his own advanced laboratory at his disposal, he had the financial resources to underwrite any research project he found promising, even writing a personal check for $5,000 to help jump-start Harvard's nuclear physics research. He was an avid supporter of leading physicist Ernest O. Lawrence and his ambitious cyclotron project -- which produced radioactive isotopes that might prove to be therapeutic or possibly provide clues to the exploitation of atomic energy -- and was using his wide influence among corporate chiefs and Washington officials to help Lawrence secure more than $1 million in grant money from the Rockefeller Foundation. He was also a first cousin of Henry Stimson, who was a member of two Republican administrations and rumored to be President Roosevelt's choice as secretary of war. Because he had Stimson's confidence, Loomis was uniquely positioned to play a pivotal role as the country prepared for a war the Germans had already demonstrated would be, in Bush's words, "a highly technical struggle."

Of course, Loomis did not need anyone's permission to undertake his own investigation of the new machinery of war. He was enthusiastic about American know-how and was not inclined to sit idly by until the military, which he viewed as slow and hidebound by tradition, finally determined it was time to take action -- particularly if just catching up with the Germans proved to be a monumental task. Long before the government moved to enlist scientists to develop advanced weapons, Loomis had assessed the situation and concluded it was critical that the country be as informed as possible about which technologies would matter in the future war. He scrapped all his experiments and turned the Tower House into his personal civilian research project, then began recruiting the brightest minds he could find to help him take measure of the enemy's capabilities and start working on new gadgets and devices for defense purposes.

How much Richards actually saw and heard at the Tower House, and how much he gleaned from Szilard or simply guessed at, is impossible to know. What had passed for science fiction and wild speculation only a short time ago was now no longer beyond imagining. His roman à clef provides a rare glimpse inside Loomis' empyrean of pure science just before they would all be cast out into a corrupt and violent world. In the final scene in his short story, Zmenov intentionally kills himself by detonating a small explosive "to prove forever that his theory is true." Richards realized the race to build the bomb was on and that the coming war would change everything. He understood that the leisurely, cloistered world of gentlemen scientists he had known at the Tower House was at an end, and the irony that his death coincided with the passing of an era did not escape him.

Years later, Kistiakowsky's widow, Elaine, would compare Richards' stories to passages in her husband's unfinished memoir, which he had been dictating into a tape recorder up to the time of his death in December 1982. She was amazed to learn how many details Richards had drawn directly from the period the two scientists had been involved with the Tower House -- from its grand beginnings in 1926 to the day it was hastily shuttered in 1940. During the decade and a half Tower House flourished, Loomis played host to a remarkable group of young scientists at a moment when new discoveries were transforming all their fields and a spirit of intellectual excitement and experimentation fueled their research. It was hard to believe that in only a few years, that bright circle would not only build the radar system that would alter the course of the war, but would go on to create a weapon that would change the world forever. "It sounds like fiction," said Elaine. "It's incredible to me now, looking back, that it really happened."

Copyright © 2002 by Jennet Conant

fromChapter 6: Restless Energy

Not long after the construction was completed in 1938, Loomis fell hopelessly in love with Hobart's twenty-nine-year-old wife, Manette. The Glass House, originally intended as guest quarters for visiting scientists, became their secret hideaway. Over time, it became Loomis' home away from home. Ironically, the house with translucent walls proved ideal for private rendezvous. Tucked away behind the laboratory on a secluded bluff overlooking Tuxedo Lake, and shielded on the other side by tall pines, it was protected from the prying eyes of neighbors. More than one of the lab's eminent guests was known to bring a mistress there for a "naughty weekend," according to Kistiakowsky's second wife, Elaine. "It became quite the place for wild parties, and it was not uncommon for people to bring out their girlfriends and have quite a good time without their wives being any the wiser for it. They were all young, and quite good-looking, and they worked hard and played hard. And I gather they drank like fish."

Apart from visitors, Loomis allowed only trusted members of his laboratory staff access to the house and instructed his own wife that it was off limits both to her and to her legions of servants. "He left strict orders that no one was ever to go in there to tidy up, supposedly because of all the special equipment that was lying about," said Evans. "I don't know if Ellen knew what was going on or not, but she alwayshatedthat house."

Loomis went to great lengths to ensure he and Manette were not discovered, even developing a signaling system that he used to communicate with her from the windows of their respective homes. The Hobarts lived on the opposite side of Tuxedo Lake, and Lescaze had situated the house perfectly on the cliff so that its windows faced the water and offered a fine vista of the mansions on the other side, including the Tower House, rising from the top of the highest hill in the park. Loomis taught Manette how to manipulate a small mirror to catch the light and worked out a series of simple signals they used to alert each other at the appointed hour that the coast was clear. No matter how many times she heard the story, Loomis' granddaughter Jacqueline Quillen was always struck by the image of the two lovers secretly flashing messages to each other across the lake. "It was a very passionate love affair," she said, adding, "and despite all the trouble it caused, it remained that way to the end."

Manette was the daughter of R. W. (Billy) Seeldrayers, a prominent Belgian lawyer and sports promoter, who became head of the Belgian Olympic Committee. She grew up in a world of jocular athletes and, by her own account, learned at an early age "to enjoy male company far more than women's." Her father pushed her to excel at a wide variety of sports, and she received instruction in everything from tennis, golf, and field hockey to soccer and even a little cricket. She became an accomplished tennis player and figure skater and briefly competed at the amateur level before giving it up to study music and art. Her family had lost most of their savings during the First World War, and her mother, ambitious for her only child to make a good marriage, tried to introduce her to "better society."

Manette met Katherine Grey Hobart in Brussels while the latter was on a European jaunt, and when the granddaughter of a distinguished American vice president invited her to return home with her, Manette's mother packed her bags. The Hobarts were exceedingly wealthy and divided their time between Carroll Hall, their elegant city residence in Paterson, New Jersey, and Ailsa Farms, the family's 250-acre country estate in Haledon. The Hobarts employed an army of servants, and the household staff alone included a cook, a kitchen maid, a parlor maid, a houseman, a butler, a laundress, an assistant laundress, two chauffeurs, and several chambermaids. They hosted "fancy dress" parties year-round at their stately forty-room mansion, and their table sparkled with Venetian glass and precious Fabergé Russian enamelware that had been designed for the czar. For twenty-two-year-old Manette, who had grown up in war-deprived Belgium and could still bitterly recall having a winter coat cut from the green felt cover of a billiard table, it must have seemed positively idyllic. In the space of a year, her betrothal to the Hobart's only son and heir was duly accomplished. They were married in Brussels in 1931 and divided their time between Ailsa Farms and Schenectady, before settling permanently in Tuxedo Park.

Never were two people more ill suited than the taciturn Hobart and his bright, athletic, puckish young bride. Garret Hobart was "pathologically shy," according to family members, and led a quiet, almost cloistered existence. He was quite content in his own little world, and the couple never entertained and had virtually no life outside the laboratory. While his neighbors considered him a bit queer but harmless, they steered clear of his "foreign" wife. Tuxedo Park was very provincial in those days, and anyone with an accent was seen as suspect. Manette's English was less than perfect, and she retained a thick Belgian accent that lent her a decidedly exotic air that the wives in the young smart set found most offputting. As a result, she had few friends and spent much of her time on her own. A talented artist, she spent her days working on her painting and sculptures, but it could not have been easy. "It was all very new to her, and she didn't really know a soul or how to get on," said Paulie Loomis. "I think the early years of her marriage must have been very lonely."

As her husband had no interest in sports, Manette took to playing tennis and golf with the young research scientists at Tower House, and more than a few became quite smitten with her, including Bill Richards. Very petite and slender, she had a superb figure that she displayed to full advantage. Although she was only passingly pretty, her emphatic sexuality made her captivating to the opposite sex. "Oh, she had a real way about her," recalled Evans, speaking with the authority of a southern belle who turned plenty of heads in her day. "She had wonderful legs, and always showed them off in little tennis skirts and golf shorts. She knew what she was doing. She was a real flirt."

Manette had a talent for making men fall in love with her, as her marriage to the unlikely Hobart attested, and she was not above using her sexuality to attract the fifty-year-old Loomis. "She absolutely seduced him," said Quillen. "I think it was about great sex, which would have been a scarce commodity in his first marriage. I think for Alfred it was an incredible, all-encompassing discovery. She gave him such enormous pleasure, and he absolutely adored her."

It is impossible to say exactly when the affair began. Both Manette and her husband were an integral part of the Loomis household and remained that way long after their relationship began. After Alfred made Garret Hobart his assistant, Ellen Loomis had taken his young wife under her wing and regarded her almost as a daughter. The two men worked together by day, dined together with their wives on a regular basis, and frequently took their families on holiday together. The Hobarts' first child, Garret Augustus Hobart IV, was born in 1935, followed by another boy, who was born in August 1937. Manette named her second son Alfred Loomis Hobart, after his beloved godfather.

According to Paulie Loomis, both Alfred and Manette were deeply unhappy for years before they became involved. "I know she was mad about him for a long time," she said. "Alfred was a wonderful-looking man, and very courtly and gentle. He could be hard to talk to unless he liked you. But once you got to know him, he was fascinating. He could explain the most complicated things and make them simple and understandable. He could unlock the secrets of the world, and it was magical. Manette was nobody's fool. Here she was married to poor Hobart, who was really an odd duck, and quite pathetic. She knew Alfred had no one, because his wife had taken to her sickbed long before that. And she knew he was the kind of man who just had to be with somebody. So she became his mistress, and she stayed married to Hobart. That was the cover-up, and I think it went on that way for a long time."

There is a striking black-and-white photograph of Manette and Loomis in a canoe that was taken in the summer of 1938 or 1939. She is happily reclining in the middle of the boat behind Loomis, who is rowing. The photo has been crudely cropped with scissors, cutting out the other oarsman, but in all likelihood it was Garret Hobart. The picture was taken at the Hobart family compound in Rangeley, Maine, the last time they were all on holiday together. "I am only guessing, but I don't think, at the time, my dad had a clue what was going on," said Al Hobart. Ellen Loomis' letters during this period reveal that she was lately "so hampered by illness" that she was not able to get out much or see friends, and it is possible she was unaware of the romance or simply chose to turn a blind eye to it. However, her condition became quite perilous again the following winter, which may have been her way of coping with the competition. As she wrote to Stimson in February 1939: "All my fever seems over now, and I know Alfred has given you the news. There is no cause for worry about me, as you always understood..."

Garret Hobart never talked about the affair between his wife and revered mentor that eventually broke up his marriage. Only once, many years later, in a moment of frustration, did he betray a hint of the anger or bitterness he must have felt. "We were in Maine, and we were getting ready to go fishing, when he said, out of the blue, 'Alfred Loomis broke the tip off my fly rod,'" recalled Al Hobart, who was seven years old when his mother finally left his father to run off with Loomis in 1944. "That was it. Just that one outburst. But I caught the whiff then of a fairly strong resentment."

In his roman à clef, Richards, who was a good friend of Hobart's, caricatured Manette as the "brazen hussy" Leone Allison:

Her wide-set brown eyes and amiable expression were photogenic. The sun had bleached her hair until it was almost white and had turned her skin, most of which was visible, to a rich brown. She wore a rudimentary halter of robin's egg blue, tiny shorts of the same color, and rope-soled sandals. A wire-haired fox terrier with a handsome moustache and an aristocratic vacant expression trotted past her into the room. Every one turned as she halted in the doorway...

Not only was her informality of dress "deeply shocking," her sexual frankness, for a woman of her day, was so surprising that it made grown men blush and left them "sputtering incoherently." She enjoyed playing "cat and mouse" games with various prey, but occasionally those she toyed with ended up falling in love with her, only to have their hearts broken. Throughout the novel, she boasts of having had affairs and admits to having an ill-considered fling with Bill Roberts, Richards' fictional alter ego, whom she "slept with...a couple of times." Roberts, she explained, had moved back to Boston and was unhappy and "drinking." But he could be very charming and persuasive, and she fell for him: "I was the only person he'd ever cared for, he said, and not having me was wrecking his life." After he had bedded her, however, it turned out he was not in love at all but had wanted only to add her to "his collection," and the two had a bitter parting of the ways.

In the novel, which Richards populated with cardboard cutouts of the famous scientists who frequented the laboratory, Leone Allison's husband, Charles Allison, the laboratory director (Garret Hobart) was portrayed as a weak-kneed, tremulous nerd who married a woman many times out of his league. As Leone (Manette) confesses in the book, her husband was aware of her infidelities, but there was nothing he could really do to stop her: "When I married Charlie I told him he wasn't the first, and he wasn't going to be the last." Nevertheless, she felt sorry for him and tried to protect him. "He thinks he just has to suffer if he doesn't like something. Why, even when he's making love, poor kid, he's sort of shy and all by himself." The only man who was truly her match, she admitted in a moment of candor, was her husband's boss -- the wealthy owner of the laboratory. "Nobody else around here appeals to me...I've always been goofy about him, but he's happily married."

Even if Richards had lived long enough to insist that his novel was not intended to "represent persons living or dead," as he wrote in his author's note, his thumbnail sketch of Manette was entirely too vivid not to be instantly recognizable to the denizens of Tower House. By all accounts, it was dead on. "Oh, it was her all right," said Evans. "As soon as you read about her parading around in short shorts, you knew." When the novel was published in the spring of 1940, Loomis was appalled at the way Manette was depicted and outraged that Richards had dared suggest in print that there was anything between them. Beginning with the laboratory setting (using a private research facility housed in a mansion as the site of the murder and a vehicle for an in-depth look at the science of brain waves) to the catalog of familiar characters and painfully personal details, Loomis knew Richards had hardly invented a single element of his story. "Alfred hated that book," said Evans. "He absolutely hated it. He wished that it had never been published."

Exactly when Loomis became aware of the book is not clear, but Richards' stunning suicide just weeks before its publication apparently cut short any legal action Loomis might have contemplated taking to quash the inflammatory novel. Although Richards' family worried that Loomis might still sue for libel, it seems unlikely, as it would surely have attracted further publicity, which was the last thing he wanted. Besides, Richards had disguised the Loomis Laboratory well enough, and nothing was ever written in the newspapers about the fictional story's surprising similarity to his Tuxedo Park establishment or the important brain wave research being done there. As far as Loomis was concerned, the best thing to do was to bury the book along with its author. He never spoke of either again. There was a rumor at the time, according to Richards' nephew Ted Conant, that Loomis bought up every copy of the novel available in New York bookstores, just to make sure that as few friends and acquaintances saw it as possible. But as the deeply chagrined Richards family also wished the book would disappear, no one would have stopped the powerful Wall Street financier from doing as he saw fit.

In all fairness, Richards' suicide must have been deeply shocking to Loomis and his family. He had been a close friend and colleague. He was among the very first of the young scientists Loomis had recruited to work with him at Tower House, and their association had lasted over fourteen years. He was still working for Loomis on a part-time basis at the time of his death, and they must have been in regular contact. Certainly, Richards had suffered bouts of depression, had occasionally drunk to excess, and had often been physically unwell, but none of those things had made him decidedly more peculiar than any of the others in Loomis' company.

Kistiakowsky, who was at Harvard by then, had been very close to Richards since their Princeton days and had known more about his "mental troubles" than anyone. Richards had confided to him in intimate detail about his tempestuous personal life. He had had a series of failed love affairs, including one with Christiana Morgan, the beautiful but volatile daughter of a Boston society family. Morgan had become a protégé of Carl Jung, and Richards, who was very taken with her, had followed her to Zurich and had even consulted Jung about his sexual problems, which he blamed on his repressive Puritan background. When Richards quit his teaching post at Princeton, he had told Kistiakowsky that his emotional state was worse and he was moving to New York to undergo intensive psychotherapy. (It is probable that Richards was manic-depressive: his father, the Harvard Nobel laureate, had suffered from myriad phobias and "nervous attacks" and had died at the age of sixty after being laid low by chronic respiratory problems and a prolonged depression; years later, Bill Richards' brother, Thayer, a prominent Virginia architect, would also commit suicide, lying down on the railroad tracks near his home.) On the last page of his novel, Richards has a character ask one of the doctors at the laboratory, "You have all heard the expression 'Genius is close to insanity.' Do you believe, as a psychiatrist, that this is essentially a representation of fact?"

After Richards' suicide in January 1940, Kistiakowsky could not duck the guilt he felt over the role he played in his friend's increasing dependency on booze. "He was an excellent conversationalist, well-versed in cultural and artistic matters, a gay companion in all the drinking parties we used to have," Kistiakowsky later recalled in his memoir. "Meanwhile he became an alcoholic. I fear that our joint drinking of bootleg alcohol that we used to doctor up into 'gin' was a critical stage on that road..."

It is doubtful Loomis ever suffered any such misgivings about Richards' death. He had already moved on. The past was done with, and all that mattered was the future. By then, he had met his new protégé, Ernest Lawrence, and was impatient to see what they could accomplish together. Paulie Loomis always admired her father-in-law's relentless quest for scientific truths but could never completely ignore its ruthless quality. "Physicists are single-minded in the pursuit of what interests them," she observed. "As people go, they can be pretty cold."

Copyright © 2002 by Jennet Conant

fromChapter 9: Precious Cargo

But first will you let me introduce my guests to you when they are all together? Some scientists are like prima donnas, you know, and they may be getting pretty nervous.

-- WR, fromBrain Waves and Death

By the summer of 1940, Britain was teetering on the edge of despair. Germany had begun relentless air attacks on England as a prelude to invasion, and Tizard, who was chairman of the key scientific committee on air defense, realized that they would not be able to stand alone for long. Hitler occupied a large part of Europe, and it was only a matter of time before England was outmatched by Germany's productive power. Tizard foresaw, with greater clarity than either the politicians or the military leaders, that the war had become harnessed to technology and technical superiority. The ability to produce powerful new weapons was the key to victory.

Convinced that Britain simply could not win without the assistance of the United States in developing and building these new instruments of war, Tizard had been lobbying vigorously for an overall exchange of scientific information of military significance. His idea was not greeted with enthusiasm at first, and Robert Watson-Watt, Britain's premier radar authority, went on record saying that the United States had nothing to offer. It did not help that an earlier fact-finding trip, headed up by the respected Nobel laureate Archibald Vivian Hill with the intention of gathering information about American science, had been a failure. Of course, with no secrets to barter and nothing to sweeten the pot, Hill had not been able to induce the Americans to divulge anything of value. But after France fell, and Hitler's forces were encamped along the Channel coast, England's new prime minister looked more favorably on Tizard's plan.

In one of the great gambles of the war, Churchill decided to support the idea of a technical mission to America and personally undertook the negotiations with Roosevelt. Events necessitated that they move very quickly. By July, the arrangements were embodied in an aide-mémoire signed by President Roosevelt and British ambassador Lord Lothian. In early August, Tizard picked the six men who were to take part in the British Technical and Scientific Mission to the United States, informally known as the Tizard Mission: Brigadier F. C. Wallace (British Army), a distinguished officer who had been in charge of the antiaircraft defenses at Dunkirk and had been one of the last men to leave the beaches; Captain H. W. Faulkner (Royal Navy), who was just back from serving in the Atlantic during the Norwegian campaign; Group Captain F. L. Pierce (Royal Air Force), who had made the first of many bomb attacks on the German destroyers hiding in the Norwegian fjords; John Cockcroft, the respected Cambridge physicist, who had built one of the first proton accelerators and at the outbreak of war became head of army research; Edward "Taffy" Bowen, a young Welsh physicist who was one of England's radar pioneers; and Arthur Woodward-Nutt, an Air Ministry official, who would serve as secretary. The plan was for Tizard to go ahead by air to Canada, which he had insisted be treated as an equal partner in the negotiations, and brief the Canadian government on what was to be disclosed to the Americans. He would then proceed to Washington to prepare the way. The rest of the mission would follow by ship.

Upon arriving in Washington on August 22, Tizard immediately made contact with Lord Lothian at the British embassy. He expected that A. V. Hill would have at least made administrative arrangements for the mission, but much to his dismay nothing had been done. "No office, no typists, etc.," he complained to his diary. "A good number of people do not know what I am here for!" As the embassy was too short on space to accommodate their needs, he hastily set up temporary headquarters at the nearby Shoreham Hotel, overlooking Rock Creek Park. Time was of the essence. Two days later, on August 24, the Luftwaffe executed a major strike against the Manston airfield and badly damaged the northeast London suburbs.

On August 26, Lothian arranged for Tizard to have an official audience with President Roosevelt. Because of the secrecy surrounding the mission, they slipped into the White House by the back door to avoid the press. Roosevelt welcomed them but seemed to be in a somewhat pessimistic frame of mind. He told them he was going to get his draft bill for conscription through Congress, but "it would probably lose him the election in November." He talked in generalities, except for explaining briefly that he was withholding the Norden bomb sight, one of the most important military secrets of the war. The device, which included an automatic pilot, used a mechanical analog computer to determine the exact moment a bomb should be dropped to accurately hit its target. It was then thought to be the key to daylight strategic bombing. The president told Tizard the reasons for not revealing it were "largely political," and if he could get evidence that the Germans had it, he could release it. Tizard then had a long meeting with the president's new secretary of war, who received him cordially.

"He seemed a very nice and sensible British scientist," Stimson observed of the Oxford-trained chemist, who had a pince-nez and the elegant manner that went with it. Stimson told Tizard to see Bush at the NDRC and recommended he talk to Compton and Loomis about radar, though he shrewdly noted that he already seemed "very well acquainted" with the scientific work being done in America. But the veteran diplomat knew that Tizard had made the trip across the Atlantic with a far more bold proposition: "He comes over here on behalf of his Government to offer us all of their secrets and hopes we may offer them some of ours."

Back in London, the six members of the secret Tizard Mission were making frantic preparations. Tizard had left them in no doubt "about the importance of the mission and the seriousness with which it was regarded" by Churchill. Their purpose, under painstakingly careful security procedures, was to hand over to the U.S. services all of their country's recent technical advances. That meant virtually every British secret: the jet engine, still in embryonic form, new antisubmarine devices, predictors, proximity fuses, explosives, and radar, in all its forms. In the hectic weeks before their departure, they rushed around collecting documentation on all the classified wartime developments: books, manuals, circuit diagrams, blueprints, films -- anything that provided factual evidence of work in progress. Cockcroft set about collecting items of classified military equipment, while Taffy Bowen, the radar specialist, gathered together all his notes on their prized RDF system. Most of it would be packed in a large black metal deed box, of the kind ordinarily found in a solicitor's office, which Cockcroft had bought at an army and navy store. The box was kept under close guard in the headquarters of the Department of Supply at Savoy House in London, where Cockcroft kept an office, until their departure.

By far the most valuable item the mission would be bringing with it was a sample of one of the first resonant cavity magnetrons, a powerful source of microwaves that had been invented only seven months earlier at Birmingham University. From the moment John Randall and Henry Boot had conceived of the idea, to the dramatic results achieved with the first unfinished laboratory model, it was clear they had made a gigantic breakthrough in radar. No bigger than the pendulum of a grandfather clock, the copper disk was capable of generating high power (ten kilowatts) and very short wavelength (ten centimeters) radio waves. Nothing like it had ever been heard of, and most scientists believed such a device would not be within reach for years. Many decades later, Bowen could still recall "the drama of the occasion" as the news sank in -- "the performance of the resonant magnetron was simply revolutionary." It would clearly lead to a new generation of compact, high-resolution radar that could breathe new life into England's beleaguered defenses and turn its planes into deadly night fighters and submarine patrollers that could operate under cover of darkness. It would also lead to the development of more accurate antiaircraft guns, which the British urgently needed to combat the dive bombers Germany was employing so effectively in advance of its armored columns.

For Britain, the magnetron was truly "a pearl beyond price." It was a technical miracle that could change the course of the war. The improved range and resolution of microwave radar could be a decisive factor in securing victory. All that was required was exploiting the new technology in a timely fashion. But in those last weeks of summer, the Luftwaffe had switched to night attacks, and sporadic bombing of London had begun. With its technical and industrial resources taxed to the breaking point, it was simply not possible for England to develop and mass-produce the new devices fast enough to make a difference in this war. Only with America's help could they capitalize on this stroke of luck. Threatened with invasion, the British could not afford to have this discovery fall into the hands of the Germans. They had to give the magnetron to the Americans if they wanted them as partners -- it would be their dowry in marriage. It was a matter of survival.

The British also knew that many American scientists were eager to help England in its crisis. Sir Mark Lawrence Oliphant, the esteemed Australian physicist who was head of the Physics Department at Birmingham University, had received a letter from Lawrence earlier that spring, offering to give them the benefit of the United States' advances in radar: "There has been a good deal of progress in this country on microwaves, and I do not know why Dr. Hill has not been able to get the information you want. I think it has to do with the commercial aspects," Lawrence wrote, referring to the complex government restrictions on the interchange of patented information. "I have given him the best advice I could." Loomis had again broached the subject of cooperation in these crucial times during his visit later that summer.

In those final weeks, Bowen made a special trip to the General Electric Company's research laboratory in the London suburb of Wembley for a detailed briefing on the new resonant magnetron. The first twelve production models had just been completed a few weeks earlier, and after they were run through a test rig, he selected the best one to take with him to the United States. As it happened, he chose number twelve, which would later turn out to be significant. A few days later, he returned to pick it up. Sticking to his usual mode of transportation to attract as little attention as possible, he carried it to London by underground and with great relief deposited it in the tin trunk, now filled to the brim with Britain's most valuable military secrets.

Though not yet thirty, Bowen was the leading defense scientist on the mission and an expert in all of the country's top-secret radar systems. He was to be "custodian of the black box" on the journey across the ocean. Bowen, with the black box, was to travel separately to the dock at Liverpool, and he was expected to find his own way to the ship in which he and the rest of the team would be making the crossing. So late on the evening of August 28, he showed up at the back door of Savoy House, where he had arranged for a guard to hand off the bulky package. Bowen took it by taxi to the Cumberland Hotel, where he had planned to store it overnight in the safe. But when the hotel manager saw the box, he shook his head in dismay -- it was larger than the safe. Bowen had no choice but to stow the kingdom's treasure chest under the bed in his locked hotel room and count the hours until morning, when he was to catch the eight-thirty A.M. boat train for Liverpool from Euston Station.

Early the next morning, Bowen hailed a taxi to take him to the station. The driver stubbornly refused to let him keep the box on the seat next to him and instead insisted on strapping it to the roof. Bowen could not afford to waste time arguing, and, as he later told the story, "We made the short run to Euston with that supremely important piece of luggage prominently displayed on the roof." At the station, things went from bad to worse, and he almost lost England's last best hope in the rush-hour stampede:

With my luggage, the box was more than I could handle, so I called a porter and told him to head for the Liverpool train. He grabbed the box, put it on his shoulder and headed off so fast that (an old cross-country runner and still pretty fit) I had great difficulty keeping up with him. He got well ahead and the only way of keeping track of him was to watch the box weaving its way through the mass of heads in front. A first class seat had been reserved for me, but beyond that I did not know what to expect. All of the other members of the Mission were going to Liverpool by different routes, and I was alone on this leg of the journey.

I found my seat and, with the black box parked on the luggage rack, waited for departure time. What I had not realised was that the whole compartment had been reserved and when I entered it all the blinds were drawn and large notices were posted on both windows. A few minutes before departure time, an exceptionally trim, well dressed gentleman with a public-school tie came into the compartment and with scarcely a glance in my direction settled down in a seat diagonally opposite readingThe Times.Not long after the train started, the late arrivals started shuffling up and down the corridor looking for an empty compartment. A couple of bright sparks opened the corridor door and said, "Here we are, chaps, this one is nearly empty," and started to enter. My companion spoke up for the first time and said, "Out. Don't you see this is specially reserved?" It was not what he said but how he said it. The would-be intruders wilted and we had no further interruptions. For the first time, I realized the precious cargo was under some kind of protection.

Bowen's instructions were to stay put in his compartment until the box was picked up by the army, so when the train came to a stop in Liverpool he remained seated. He noticed that his silent companion also showed no signs of leaving and appeared completely absorbed in hisTimes.Bowen gradually became aware of the sound of marching feet, and soon a squad of a dozen fully armed soldiers materialized on the platform. Led by a sergeant, they executed a series of complicated maneuvers and, "with much slapping of rifle butts," came to a halt alongside his compartment. On a barked command from the sergeant, they stood at ease, and Bowen watched as one member of the squad stepped forward and opened the compartment door: "Another two collected the black box and trundled it outside. On a further word of command, they shouldered it and marched off in the direction of the ship." Throughout the impressive performance, his dapper companion had "not moved a muscle." The moment the squad left, however, "he rolled up his newspaper and, with a barely perceptible nod in my direction, took his departure into the corridor."

The presence of such a large military escort was quite comforting, and the young physicist was just starting to relax when a terrible thought crossed his mind: "I was beginning to feel that things were well looked after," he would later recall. "Alternatively, if this was the enemy making off with Britain's secrets, they were making a spectacular job of it."

Bowen hurriedly boarded the ship, theDuchess of Richmond,and ascertained that the black box had indeed been delivered and was under guard on the bridge. He was informed that the captain's instructions were that "in the event of an enemy attack and a likelihood of the vessel being lost, the box was to be heaved over the side and allowed to sink in the mid-Atlantic." Only the group secretary, Woodward-Nutt, would be allowed access to the black box during the voyage. It was arranged that he would meet a third officer, who kept the keys to the locked strong room, should they need to dump their secret cargo into the drink.

They set sail that evening as darkness fell and headed for the Irish Sea. They had not gone far when bombs started to drop from the sky, falling all around them. Nighttime bombings were not uncommon, and it was probably part of an air raid on Liverpool. Fortunately, the Germans were not lucky that night, and none of the stray warheads struck the ship. But it was enough to stop them for the night, and they dropped anchor. The next morning they set off again, flanked by boats that served as minesweepers for the hazardous journey down the Mersey River. TheDuchesswas an unescorted Canadian passenger liner and relied on speed to make the crossing safely. To elude German U-boats, she made regular course changes every twenty to thirty minutes. It made for a rough passage, Bowen recalled, and the boat earned the nickname the "Drunken Duchess" for the way she would "roll all over the high seas."

The six members of the mission were accompanied on their journey by a thousand British sailors, brought over to man the first of the fifty overage destroyers that the American government was providing in exchange for the use of Britain's naval bases in the West Indies. (Known as the "destroyers for bases" deal, it laid the seeds for the lend-lease bill, which Roosevelt proposed in response to Churchill's desperate request that December that America provide Britain with the guns, tanks, and ships "to finish the job" and defeat Germany.) Rumor had spread among all the navy men that a famous physicist was on board, and they asked if Cockcroft could find the time to give a lecture during the week's voyage. As he could scarcely talk about his assignment or any of the contents of the black box, Cockcroft searched for a safe topic with which to entertain the bored servicemen. His choice, ironically, was atomic energy, still considered years away from being realized and of no possible importance to the war. He greatly impressed his audience, however, when he informed them that the potential amount of atomic energy in a cup of water could blow a fifty-thousand-ton battleship one foot out of the sea.

The rest of the trip was uneventful, though Bowen would always remember a conversation he had with Cockcroft in the bar one evening before dinner as an example of the kind of calculation only a physicist would make. Cockcroft had been worrying about their secret cargo and posed the question to Bowen that if the ship were indeed attacked, and the trunk thrown overboard, would it sink or swim? Cockcroft's conclusion was "open and shut": the black box and all it contained would surely float. Bowen gave the matter no more thought until he saw the box again when they sailed into Halifax harbor in Nova Scotia on September 6. Waiting on shore was an armored vehicle loaded with submachine guns, accompanied by an even bigger armed guard than the one that met the train, to transport the black box to Washington. As the box was being moved, Bowen's eyes widened in surprise -- "a neat pattern of holes had been drilled in each end." Cockcroft had apparently seen to it that the crate would sink.

Woodward-Nutt turned over the secret cargo to the Canadian military guard to transport to the border, where it was to be given to American authorities and taken directly to the British embassy in Washington. But upon his arrival at the embassy a few days later, he "was a bit shaken to find that the samples and documents that I had seen so carefully off at Halifax had not yet arrived." After a series of frantic phone calls, the missing bounty was located and sent along its way. When it finally arrived on September 9, the black box was stashed in the embassy's wine cellar, and the sole key to the door was entrusted to the ambassador's butler.

Copyright © 2002 by Jennet Conant

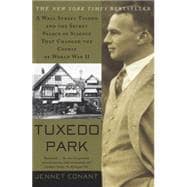

Excerpted from Tuxedo Park: A Wall Street Tycoon and the Secret Palace of Science That Changed the Course of World War II by Jennet Conant

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.