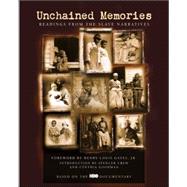

- Unchained Memories carries the same title as HBO's lead documentary for 2003 commemorating Black History month and draws on the same original source material.

Author Biography

Spencer Crew is the director of the National Underground Freedom Center and the former director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Cynthia Goodman, a writer, curator, and expert on digital media, is organizing the exhibition of Unchained Memories for the Freedom Center.

Table of Contents

| Foreword | 9 | (3) | |||

|

|||||

| Introduction | 12 | (9) | |||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

21 | (15) | |||

|

|||||

|

36 | (19) | |||

|

|||||

|

55 | (12) | |||

|

|||||

|

67 | (20) | |||

|

|||||

|

87 | (16) | |||

|

|||||

|

103 | (15) | |||

|

|||||

|

118 | (17) | |||

|

|||||

|

135 | (18) | |||

|

|||||

| Contributing Authors | 153 | (2) | |||

| Suggested Reading | 155 | (2) | |||

| Narratives Source List | 157 | (1) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 158 | (1) | |||

| Picture Credits | 159 | (1) | |||

| Documentary/Exhibition | 160 |

Supplemental Materials

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Excerpts

Slave Auctions

Nothing symbolizes the fragility and inequities of slave life better than the slave auction. Hundreds of thousands of slaves throughout the South experienced the uncertainty, the humiliation, the fear, and the psychological shock that accompanied the domestic slave trade. Yet even for slaves who did not personally experience the slave trade, the slave auction cast a painful shadow over their lives, their hopes for their families, and their belief that "a better day is a-coming."

The end of the International Slave Trade in 1808, coupled with the rapid expansion of plantations into the newly developed regions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, led to a renewed demand for slave labor, which was satisfied, in part, by the creation of a system of local and regional slave traders. This domestic slave trade ran the gamut from large businesses located in nearly every major southern city that held regularly scheduled auctions to smaller entities that brought coffles of slaves to the agrarian areas to sell. Usually slave auctions were advertised in local newspaper columns that listed the number and gender of the slaves for sale and often chronicled their particular skills as artisans, strong field hands, or seamstresses, for example. The auction usually allowed for a period of humiliating inspection and then the slave was led to an elevated stand or auction block. The planters would then shout out their bids and the slave was sold to the highest bidder. The cost for acquiring slaves varied throughout the nineteenth century, depending upon the region and the gender and age of the slave. At the time of the War of 1812, an adult male field hand cost nearly $300, with skilled artisans such as blacksmiths and carpenters costing more. By 1858 in northern Virginia, a prime field hand cost $1,350, with skilled slaves selling for $1,500. Slave women, especially those in the childbearing years, were highly valuable, with some female slaves selling for as much as $1,800 in the years just before the Civil War.

While it is difficult to calculate the number of slaves who went through an auction, the fear and dread of that experience permeated all aspects of slave life and culture. Several of the most venerated spirituals described heaven as a place that had "no more auction blocks for me." And an array of children's songs expressed concern about the stability of the slave family. One song included the line, "Mother, is massa gonna sell us tomorrow?" Why did the specter of the slave auction cast such a long shadow? In many ways, the threat of being sold reflected the capriciousness of a slave's life. The slave's world could change in an instant based on the whims of the owner. Slaves were sold for almost any reason, from the need to settle an estate to an owner's displeasure with a particular slave. In fact, the threat of selling a slave became one of an owner's weapons to enforce discipline and exercise control over the black populace. The fear of being "sold south" was very much a way of life for most slaves. In actuality, so many slaves experienced the auction block that slave life was forced to change throughout the nineteenth century. In the small county of Loudon, Virginia, for example, nearly 7,000 slaves were "sold south."

The domestic slave trade had a devastating impact on African-American life in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Much of the strain fell upon the families, which were easily and often callously disrupted and destroyed when a member was sold. It became very difficult to maintain any semblance of a traditional nuclear family. As the Civil War neared, states in the upper South such as Virginia had a large number of enslaved children who were orphaned by the slave trade. In 1859, nearly 18 percent of the children of slaves had little or no contact with either parent. Marriages also suffered if spouses were separated to meet the economic needs of the slaveowner. Some marriages survived if the couple was only separated by a few miles, commonly known as "marrying abroad." But most couples that were sold rarely saw each other again. The slave trade ensured, according to a Virginia Quaker, that "these people are without their consent torn from their homes, husbands and wives are frequently separated and sold into distant parts, children are taken from their parents without regard to the ties of nature, and the most endearing bonds of affection are broken forever."

Even freedom did not erase the pain and sense of loss that stemmed from the auction block. For many years after the Civil War ended, the newly freed men and women searched throughout the South for the families that were torn from them. Henry Watson recalled how he searched for his mother in the Reconstruction South: "Every exertion was made on my part to find her, or hear some tidings of her. But all my efforts were unsuccessful; and from that day I have never seen or heard from her." So many former slaves were haunted by the sale of loved ones that their search continued for more than a decade. Well into the 1870s and 1880s, African-American newspapers were filled with columns entitled "Information Wanted." These columns contained painful pleas for information about family members who had been separated by slavery. A column from 1870 carries a notice by Charles Gatson, who sought "information of his children, Sam and Betsy Gatson who were sold by a slave trader to go further south to Mississippi or Louisiana. They are now about 22 to 25 years old and were taken away in 1861."

African Americans wrestled with the stigma of the slave auction for many years after the end of slavery. Despite the real losses that the enslaved suffered, African Americans did raise families, maintain marriages, and struggle to find ways to exercise control over their lives in the face of the realization that their bodies were owned by the master.

Lord child, I remember when I was a little boy, 'bout ten years, the speculators come through Newton with droves of slaves. They always stay at our place. The poor critters nearly froze to death. They always come `long on the last of December so that the niggers would be ready for sale on the first day of January. Many the time I see four or five of them chained together. They never had enough clothes on to keep a cat warm. The women never wore anything but a thin dress and a petticoat and one underwear. I've seen the ice balls hangin' on to the bottom of their dresses as they ran along, jes like sheep in a pasture 'fore they are sheared. They never wore any shoes. Jes run along on the ground, all spewed up with ice. The speculators always rode on horses and drove the pore niggers. When they get cold, they make 'em run 'til they are warm again.

The speculators stayed in the hotel and put the niggers in the quarters jes like droves of hogs. All through the night I could hear them mournin' and prayin'. I didn't know the Lord would let people live who were so cruel. The gates were always locked and they was a guard on the outside to shoot anyone who tried to run away. Lord miss, them slaves look jes like droves of turkeys runnin' along in front of them horses.

I remember when they put 'em on the block to sell 'em. The ones 'tween 18 and 30 always bring the most money. The auctioneer he stand off at a distances and cry 'em off as they stand on the block. I can hear his voice as long as I live.

If the one they going to sell was a young Negro man this is what he say: "Now gentlemen and fellow-citizens here is a big black buck Negro. He's stout as a mule. Good for any kin' o' work an' he never gives any trouble. How much am I offered for him?" And then the sale would commence, and the nigger would be sold to the highest bidder.

If they put up a young nigger woman the auctioneer cry out: "Here's a young nigger wench, how much am I offered for her?" The pore thing stand on the block a shiverin' an' a shakin' nearly froze to death. When they sold, many of the pore mothers beg the speculators to sell 'em with their husbands, but the speculator only take what he want. So maybe the pore thing never see her husban' agin.

W. L. BOST, North Carolina

Dey talks a heap 'bout de niggers stealin'. Well, you know what was de fust stealin' done? Hit was in Afriky, when de white folks stole de niggers jes' like you'd go get a drove o' hosses and sell 'em. Dey'd bring a steamer down dere wid a red flag, 'cause dey knowed dem folks liked red, and when dey see it dey'd follow it till dey got on de steamer. Den when it was all full o' niggers dey'd bring 'em over here and sell 'em.

SHANG HARRIS, Georgia

Talkin' 'bout somethin' awful, you should have been dere. De slave owners was shoutin' and sellin' chillen to one man and de mama and pappy to 'nother. De slaves cries and takes on somethin' awful. If a woman had lots of chillen she was sold for mo', 'cause it a sign she a good breeder.

Right after I was sold to Massa Dunn, dere was a big up-risin' in Tennessee and it was 'bout de Union, but I don't know what it was all about, but dey wanted Massa Dunn to take some kind of a oath, and he wouldn't do it and he had to leave Tennessee. He said dey would take de slaves `way from him, so he brought me and Sallie Armstrong to Texas. Dere he trades us to Tommy Ellis for some land and dat Massa Ellis, he de best white man that ever lived. He was so good to us we was better off dan when we's free.

MILLIE WILLIAMS, Texas

My mother was separated from her mother when she was three years old. They sold my mother away from my grandmother. She didn't know nothing about her people. She never did see her mother's folks. She heard from them. It must have been after freedom. But she never did get no full understanding about them. Some of them was in Kansas City, Kansas. My grandmother, I don't know what became of her.

When my mother was sold into St. Louis, they would have sold me away from her but she cried and went on so that they bought me too. I don't know nothing about it myself, but my mother told me. I was just nine months old then.

MARY ESTES PETERS, Arkansas

Now my father, he was a fighter. He was mean as a bear. He was so bad to fight and so troublesome he was sold four times to my knowing and maybe a heap more times. That's how come my name is Falls, even if some does call me Robert Goforth. Niggers would change to the name of their new marster, every time they was sold. And my father had a lot of names, but kep the one of his marster when he got a good home. That man was Harry Falls. He said he'd been trying to buy father for a long time, because he was the best waggoner in all that country abouts. And the man what sold him to Falls, his name was Collins, he told my father, "You so mean, I got to sell you. You all time complaining about you dont like your white folks. Tell me now who you wants to live with. Just pick your man and I will go see him." Then my father tells Collins, I want you to sell me to Marster Harry Falls. They made the trade. I disremember what the money was, but it was big. Good workers sold for $1,000 and $2,000. After that the white folks didn't have no more trouble with my father. But he'd still fight. That man would fight a she-bear and lick her every time.

ROBERT FALLS, Tennessee

I never knowed my age till after de war, when I's set free de second time, and then marster gits out a big book and it shows I's 25 year old. It shows I's 12 when I is bought and $800 is paid for me. That $800 was stolen money, 'cause I was kidnapped and dis is how it come:

My mammy was owned by John Williams in Petersburg, in Virginia, and I come born to her on dat plantation. Den my father set 'bout to fit me free, 'cause he a full-blooded Indian and done some big favor for a big man high up in de courts, and he gits me set free, and den Marster Williams laughs and call me "free boy."

Then one day along come a Friday and that a unlucky star day and I playin' round de house and Marster Williams come up and say, "Delis, will you `low Jim walk down the street with me?" My mammy say, "All right, Jim, you be a good boy," and dat de las' time I ever heard her speak, or ever see her. We walks down whar de houses grows close together and pretty soon comes to de slave market. I ain't seed it 'fore, but when Marster Williams says, "Git up on de block," I got a funny feelin', and I knows what has happened. I's sold to Marster John Pinchback and he had de St. Vitus dance and he likes to make he niggers suffer to make up for his squirmin' and twistin' and he the bigges' debbil on earth.

JAMES GREEN, Texas

I was growed up when the war come, an' I was a mother befo' it closed. Babies was snatched from dere mother's breas' an' sold to speculators. Chilluns was separated from sisters an' brothers an' never saw each other ag'in.

Course dey cry; you think dey not cry when they was sold lak cattle? I could tell you 'bout it all day, but even den you couldn't guess de awfulness of it.

I never seed none of my brothers an' sisters 'cept brother William. Him an' my mother an' me was brought in a speculator's drove to Richmon' an' put in a warehouse wid a drove of other niggers. Den we was all put on a block an' sol' to de highes' bidder.

DELIA GARLIC, Alabama

I was tol' there was a lot of slave speculators in Chester to buy some slaves for some folks in Alabama. I `members dat I was took up on a stan' an' a lot of people come 'roun' an' felt my arms an' legs an' chist, an' ast me a lot of questions. Befo' we slaves was took to de tradin' post Ol' Marsa Crawford tol' us to tell eve'ybody what ast us if we'd ever been sick to tell 'em dat us'd never been sick in our life. Us had to tell 'em all sorts of lies for our Marsa or else take a beatin'.

I was jes' a li'l thang; tooked away from my mammy an' pappy, jes' when I needed 'em mos'.

MINGO WHITE, Alabama

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Unchained Memories Copyright © 2002 by Home Box Office, a division of Time Warner Entertainment, L.P.

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.